Abstract

Many lineage-specific developmental regulator genes are transcriptionally primed in embryonic stem (ES) cells; RNA PolII is bound at their promoters but is prevented from productive elongation by the activity of polycomb repressive complexes (PRC) 1 and 2. This epigenetically poised state is thought to enable ES cells to rapidly execute multiple differentiation programs and is recognized by a simultaneous enrichment for trimethylation of lysine 4 and trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 (bivalent chromatin) across promoter regions. Here we show that the chromatin profile of this important cohort of genes is progressively modified as ES cells differentiate toward blood-forming precursors. Surprisingly however, neural specifying genes, such as Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1, remain bivalent and primed even in committed hemangioblasts, as conditional deletion of PRC1 results in overt and inappropriate expression of neural genes in hemangioblasts. These data reinforce the importance of PRC1 for normal hematopoietic differentiation and reveal an unexpected epigenetic plasticity of mesoderm-committed hemangioblasts.

Introduction

Tractable mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells in which differentiation pathways can be accurately modeled in vitro and in vivo has revolutionized our understanding of lineage specification1 and provided critical information on the linear relationships between precursor cells and their progeny.2-4 Using a well-characterized model of hematopoietic differentiation,3-5 we have investigated stage-specific changes in chromatin at specific genes in ES cells upon mesoderm induction. Undifferentiated ES cells contain hyperdynamic chromatin6 where much of the genome is transcribed at a low level7 and many developmental regulator genes are transcriptionally primed and “bivalently marked” with histone modifications associated with both gene activation (such as trimethylation of lysine 4 of histone 3 [H3K4me3]) and polycomb-mediated repression (such as trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone 3 [H3K27me3]).8-10 This marking is thought to reflect the lineage plasticity of ES cells because it is resolved on differentiation (eg, in neural precursors10,11 ) and regained upon reprogramming of differentiated cells to induced pluripotent stem cells.12 Initial comparisons between ES, hematopoietic stem cells, and lymphocytes showed reduced chromatin accessibility and loss of bivalent marking in hematopoietic cells8 but did not evaluate whether such changes occurred before, coincident with, or after cells become functionally restricted. By examining the chromatin status of a panel of genes in intermediate stages of differentiation, we show here that several lineage-inappropriate (neural-specifying) genes remain bivalent and transcriptionally poised in committed hemangioblasts because the removal of polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) activity results in overt gene derepression.

Methods

Cell culture and differentiation

Bry-GFP5 and Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/Cre-ERT213 ES cells were cultured and differentiated as described.5 Embryoid bodies were dissociated, stained using a phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-Flk1 antibody (BD Biosciences) and cells sorted on GFP (Bra/T) and Flk1 expression by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Hematopoietic potential was tested using colony assays as described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Epigenetic analysis

Replication timing and gene expression were analyzed using previously published methods.14 Embryoid bodies were BrdU pulse-labeled before dissociation and sorting. Chromatin from Bra/T-GFP+/Flk1+ cells was immunoprecipitated as described in supplemental Methods.

Results and discussion

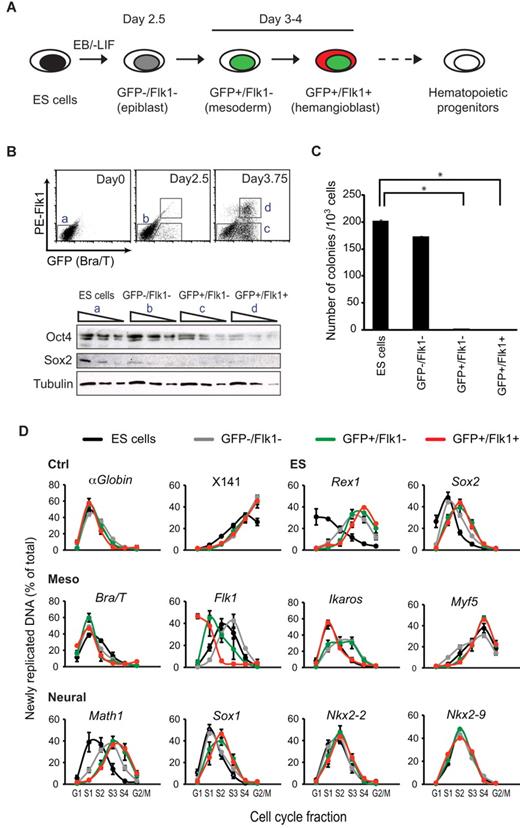

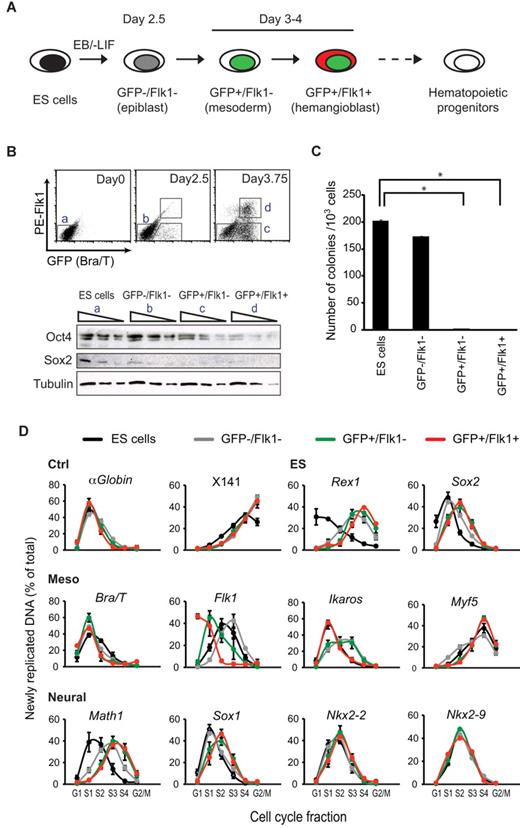

Bry-GFP ES cells that carry a GFP reporter under the control of the mesoderm-associated Brachyury (Bra/T) gene3,5 were differentiated into embryoid bodies and cells representing epiblast (GFP−/Flk1−, day 2.5), early mesoderm (GFP+/Flk1−, day 3.75), and hemangioblast stages (GFP+/Flk1+, day 3.75) of differentiation were isolated by FACS, as previously described5 (Figure 1A-B) and verified by expression analysis. Expression of pluripotency-associated factors declined (Oct4/Pou5f1) or was lost (Rex1/Zfp42, Sox2) on differentiation, whereas mesoderm-associated genes (such as Bra/T, Flk1/Kd, and Ikaros/Ikzf5) were induced, and genes important for neuroectoderm specification were detected only at low levels (Math1/Atoh1, Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1)15-18 similar to undifferentiated ES cells (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 1A). Importantly, epiblast-stage cells readily formed colonies when replated in ES media (170/1000 cells), but this capacity was not retained by cells expressing Bra/T-GFP (Figure 1C), consistent with a loss of pluripotency and commitment to mesoderm at this stage.

Progressive changes in the replication timing of developmental regulator genes upon mesodermal differentiation of ES cells. (A) Isolation of cells at sequential stages of ES cell induction to hematopoietic progenitors. Bry-GFP ES cells were differentiated in embryoid bodies (EB), harvested at different times and samples isolated by FACS sorting on the basis of GFP and Flk1 expression.5 (B) Top panel: GFP (Bra/T) and Flk1 expression by ES cells (day 0) and in dissociated embryoid bodies (2.5, 3.75 days of differentiation). Bottom panel: Western blot analysis of Oct4 and Sox2 levels in sequential 3-fold dilutions of whole cell extracts from ES and FACS-sorted cell populations a, b, c, and d. Detection with tubulin antibody is shown as a loading control. (C) Equal numbers of undifferentiated ES cells and FACS-sorted differentiated cell populations were replated in ES cell medium containing LIF for 10 days on feeder layers and colonies scored after staining with methylene blue. Data are mean ± SD from 2 experiments carried out in triplicate. *Significantly different numbers of colonies compared with ES cells (P < .05, Student t test). (D) Replication timing of control loci (αGlobin, X141), ES- (Rex1 and Sox2), mesodermal- (Bra/T, Flk1, Ikaros, and Myf5), and neural-specific genes (Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9) in undifferentiated ES cells (black), and ES-derived GFP−/Flk1− (epiblast, gray), GFP+/Flk1− (mesoderm, green), and GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast, red) samples. The nonexpressed nonbivalent Myf5 locus replicates late throughout, whereas the replication profile of Ikaros, a bivalent locus, is variable (according to developmental stage) but remains early. For each locus, the abundance of newly replicated DNA was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 6 cell-cycle fractions: G1, S1 to S4, and G2/M as described in supplemental Figure 2. Values are the amount of newly synthesized DNA, calculated as a percentage of total (sum of all fractions). Data are mean ± SD from 2 or 3 experiments.

Progressive changes in the replication timing of developmental regulator genes upon mesodermal differentiation of ES cells. (A) Isolation of cells at sequential stages of ES cell induction to hematopoietic progenitors. Bry-GFP ES cells were differentiated in embryoid bodies (EB), harvested at different times and samples isolated by FACS sorting on the basis of GFP and Flk1 expression.5 (B) Top panel: GFP (Bra/T) and Flk1 expression by ES cells (day 0) and in dissociated embryoid bodies (2.5, 3.75 days of differentiation). Bottom panel: Western blot analysis of Oct4 and Sox2 levels in sequential 3-fold dilutions of whole cell extracts from ES and FACS-sorted cell populations a, b, c, and d. Detection with tubulin antibody is shown as a loading control. (C) Equal numbers of undifferentiated ES cells and FACS-sorted differentiated cell populations were replated in ES cell medium containing LIF for 10 days on feeder layers and colonies scored after staining with methylene blue. Data are mean ± SD from 2 experiments carried out in triplicate. *Significantly different numbers of colonies compared with ES cells (P < .05, Student t test). (D) Replication timing of control loci (αGlobin, X141), ES- (Rex1 and Sox2), mesodermal- (Bra/T, Flk1, Ikaros, and Myf5), and neural-specific genes (Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9) in undifferentiated ES cells (black), and ES-derived GFP−/Flk1− (epiblast, gray), GFP+/Flk1− (mesoderm, green), and GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast, red) samples. The nonexpressed nonbivalent Myf5 locus replicates late throughout, whereas the replication profile of Ikaros, a bivalent locus, is variable (according to developmental stage) but remains early. For each locus, the abundance of newly replicated DNA was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 6 cell-cycle fractions: G1, S1 to S4, and G2/M as described in supplemental Figure 2. Values are the amount of newly synthesized DNA, calculated as a percentage of total (sum of all fractions). Data are mean ± SD from 2 or 3 experiments.

As accessible chromatin domains tend to replicate earlier in S-phase than heterochromatic condensed domains,19 we used replication timing analysis to assess dynamic chromatin changes accompanying differentiation.8,20-22 Temporal replication of ES-associated (Rex1 and Sox2), mesoderm-associated (Bra/T, Flk1, Ikaros, and Myf5), and neuroectoderm-associated (Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9) genes was evaluated at different stages of hemangioblast differentiation (Figure 1D; summarized in supplemental Figure 1B) using established methods and controls.14 As anticipated, Rex1 and Sox2 replication was earlier in ES cells (black lines) than hemangioblasts (red lines), consistent with reduced chromatin accessibility and gene expression upon differentiation, whereas replication of constitutively accessible (α-Globin) or heterochromatic (X141) controls remained unaffected. Three mesoderm-associated genes showed slight (Bra/T, Ikaros) or significantly (Flk1) advanced replication in response to differentiation, whereas neural-specifying genes either retained early replication profiles throughout (Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1) or, in the case of Math1, were delayed progressively upon differentiation (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 1B). These data showed that, although mesoderm commitment results in changed epigenetic profiles, several genes encoding neural specifiers remained early replicating in hemangioblasts in contrast to lymphocytes and hematopoietic stem cell lines (FDCPmix A4 and Pax5−/− pro-B) characterized previously8 (summarized in supplemental Figure 1B).

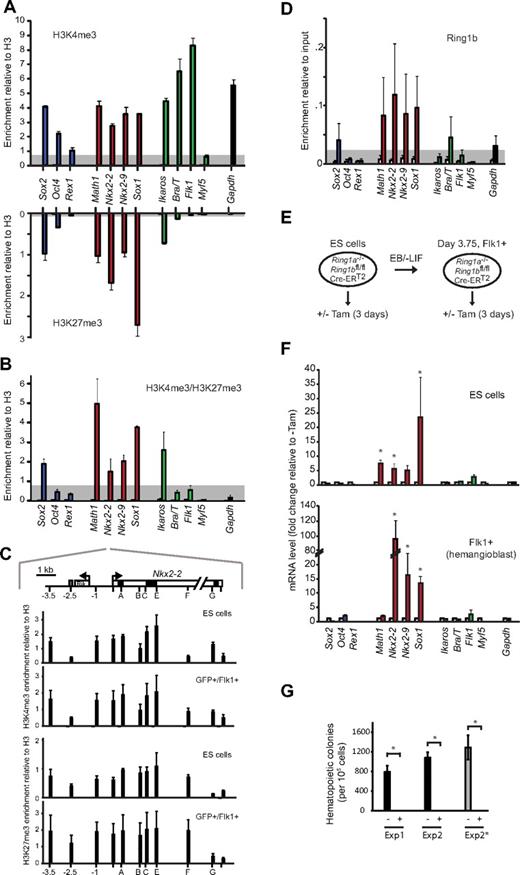

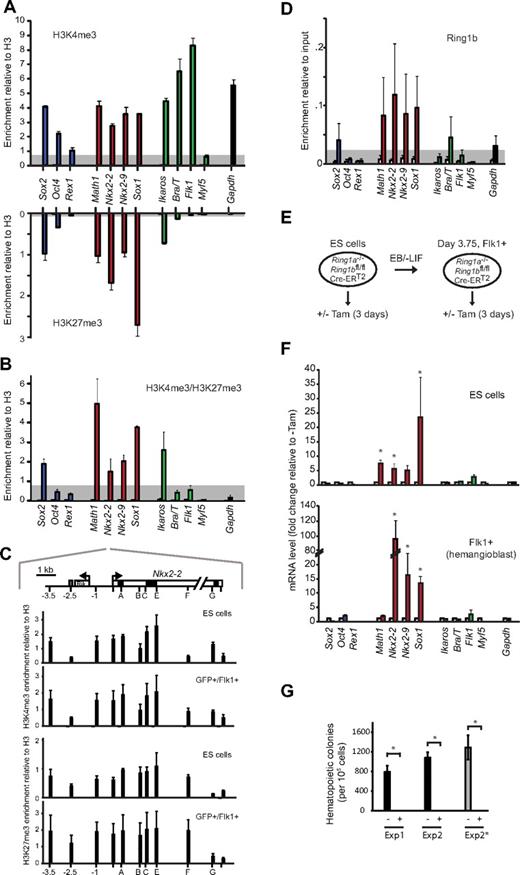

To directly determine whether these promoters were bivalently marked in hemangioblasts, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) on purified Bra/T-GFP+/Flk1+ samples, using antibodies specific for H3K4me3, H3K27me3, and total H3. Previous reports had shown that the promoters of Bra/T, Flk1, Ikaros, Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9 (but not Myf5) are bivalent in mouse ES cells.10 In hemangioblasts, we detected H3K4me3 at the promoters of expressed genes (Bra/T, Flk1, green, Figure 2A), whereas H3K4me3/H3K27me3 was codetected at Ikaros, Sox2, Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9. Similar bivalent marking of these genes was observed in CD41+-enriched hematopoietic progenitor populations (data not shown). Verification that the neural-associated genes Sox2, Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9 contained bivalently marked chromatin was shown by sequential ChIP9 in which H3K4me3-containing fragments were enriched by a second round of precipitation with antibodies to H3K27me3 (Figure 2B). Furthermore, locus-wide profiling of Nkx2-2, a gene-poor region on mouse chromosome 2 that has been extensively characterized as a prototype “bivalent domain” in ES cells,9,23 showed that the distributions of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 were largely preserved in Bra/T-GFP+/Flk1+ hemangioblasts (Figure 2C).

Bivalent chromatin and PRC1-mediated repression of neural genes is retained in hemangioblast-committed cells. (A) Analysis of modified histones at the promoters of ES- (Sox2, Oct4, and Rex1; blue bars), neural- (Math1, Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1; red bars), mesodermal- (Ikaros, Bra/T, Flk1, and Myf5; green bars), and control genes (Gapdh, black bar) by immunoprecipitation of chromatin from FACS-sorted GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells using antibodies specific for H3K4me3 (top panel) or H3K27me3 (bottom panel). Enrichment was measured by quantitative real-time PCR and is presented relative to total H3. As a control, IgG (open bars) was used for ChIP in parallel (values for most genes were low and barely visible). Data are mean ± SD of 4 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at negative control loci (Myf5 for H3K4me3, Flk1 for H3K27me3), are indicated in gray. (B) Sequential ChIP analysis of GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells using first anti-H3K4me3 followed by a second round of immunoprecipitation using anti-H3K27me3 antibody (filled bars) or nonspecific IgG control (open bars). Genes are color-coded as in panel A. Data are mean ± SD of 3 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at a negative control locus (Flk1), is indicated in gray. (C) Domain-wide profiling of histone methylation along the Nkx2-2 locus; the positions of a conserved upstream control element (gray), the transcription start site (arrow), coding regions (black), UTR (light gray), an adjacent gene (Rik), and PCR amplicons are indicated in the top panel, where scale = 1 kb. Enrichment of H3K4me3 (top) and H3K27me3 (bottom) across the Nkx2-2 locus was assessed by ChIP using IgG as controls (white bars, barely visible) in ES and GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. (D) ChIP analysis of GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) samples using anti-Ring1b antibody (filled bars) or IgG (open bars). Enrichment levels were measured by real time-PCR and are expressed relative to 10% input. Genes are color-coded as in panel A. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at the expressed (Ring1b−) Flk1 locus, are indicated in gray. (E) Strategy for withdrawal of Ring1a/Ring1b activity from CreERT2 ES cells, or from differentiated hemangioblasts, based on tamoxifen treatment (3 days). (F) Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis of candidate gene expression (color-coded as in panel A), in Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/Cre-ERT2 undifferentiated ES cells (top panel) or embryoid body-derived Flk1+ hemangioblast cells (bottom panel) 3 days after addition of 800nM tamoxifen (Tam) to delete Ring1b (colored bars) versus untreated controls (white bars). Values were normalized to a housekeeping gene (Hmbs) and expressed as fold change relative to untreated. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *Significantly up-regulated expression in tamoxifen-treated samples (P < .05, Student t test). (G) Hematopoietic colony assays were performed in triplicate for untreated (−) and tamoxifen-treated (+) samples; FACS-sorted Flk1+ Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/CreERT2 cells were replated in differentiation medium (Exp1 and Exp2) or blast medium (Exp2*) with or without tamoxifen for 3 days before dissociation and scored 6 days after replating in semisolid hematopoietic medium. *Significantly different numbers of colonies in treated compared with untreated samples (P < .05, Student t test).

Bivalent chromatin and PRC1-mediated repression of neural genes is retained in hemangioblast-committed cells. (A) Analysis of modified histones at the promoters of ES- (Sox2, Oct4, and Rex1; blue bars), neural- (Math1, Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1; red bars), mesodermal- (Ikaros, Bra/T, Flk1, and Myf5; green bars), and control genes (Gapdh, black bar) by immunoprecipitation of chromatin from FACS-sorted GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells using antibodies specific for H3K4me3 (top panel) or H3K27me3 (bottom panel). Enrichment was measured by quantitative real-time PCR and is presented relative to total H3. As a control, IgG (open bars) was used for ChIP in parallel (values for most genes were low and barely visible). Data are mean ± SD of 4 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at negative control loci (Myf5 for H3K4me3, Flk1 for H3K27me3), are indicated in gray. (B) Sequential ChIP analysis of GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells using first anti-H3K4me3 followed by a second round of immunoprecipitation using anti-H3K27me3 antibody (filled bars) or nonspecific IgG control (open bars). Genes are color-coded as in panel A. Data are mean ± SD of 3 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at a negative control locus (Flk1), is indicated in gray. (C) Domain-wide profiling of histone methylation along the Nkx2-2 locus; the positions of a conserved upstream control element (gray), the transcription start site (arrow), coding regions (black), UTR (light gray), an adjacent gene (Rik), and PCR amplicons are indicated in the top panel, where scale = 1 kb. Enrichment of H3K4me3 (top) and H3K27me3 (bottom) across the Nkx2-2 locus was assessed by ChIP using IgG as controls (white bars, barely visible) in ES and GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) cells. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. (D) ChIP analysis of GFP+/Flk1+ (hemangioblast) samples using anti-Ring1b antibody (filled bars) or IgG (open bars). Enrichment levels were measured by real time-PCR and are expressed relative to 10% input. Genes are color-coded as in panel A. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. Threshold levels, based on the enrichment at the expressed (Ring1b−) Flk1 locus, are indicated in gray. (E) Strategy for withdrawal of Ring1a/Ring1b activity from CreERT2 ES cells, or from differentiated hemangioblasts, based on tamoxifen treatment (3 days). (F) Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR analysis of candidate gene expression (color-coded as in panel A), in Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/Cre-ERT2 undifferentiated ES cells (top panel) or embryoid body-derived Flk1+ hemangioblast cells (bottom panel) 3 days after addition of 800nM tamoxifen (Tam) to delete Ring1b (colored bars) versus untreated controls (white bars). Values were normalized to a housekeeping gene (Hmbs) and expressed as fold change relative to untreated. Data are mean ± SD from 3 experiments. *Significantly up-regulated expression in tamoxifen-treated samples (P < .05, Student t test). (G) Hematopoietic colony assays were performed in triplicate for untreated (−) and tamoxifen-treated (+) samples; FACS-sorted Flk1+ Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/CreERT2 cells were replated in differentiation medium (Exp1 and Exp2) or blast medium (Exp2*) with or without tamoxifen for 3 days before dissociation and scored 6 days after replating in semisolid hematopoietic medium. *Significantly different numbers of colonies in treated compared with untreated samples (P < .05, Student t test).

Bivalent marking of developmental regulator genes in ES cells is associated with a primed transcriptional state in which RNA polymerase II is bound, phosphorylated at Serine 5, but prevented from elongating by polycomb repressive complexes; removal of PRC1 or PRC2 results in inappropriate gene up-regulation (derepression).8,23 Abundant PRC1 transcripts (Ring1a, Ring1b, Mel18, and Bmi1) and Ring1b protein was detected in both undifferentiated ES cells and cells at successive stages of hemangioblast differentiation (supplemental Figure 3A-B) and ChIP analysis showed Ring1b binding at Math1, Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9 promoters in Bra/T-GFP+Flk1+ cells (Figure 2D). To ask whether these genes were indeed functionally primed in mesoderm-committed hemangioblasts, we used Ring1a-deficient ES cells where PRC1 activity can be withdrawn on tamoxifen-induced Ring1b removal (CreERT2 cells13 ; Figure 2E). Removal of Ring1b in Flk1+ hemangioblasts (supplemental Figure 3C-D) resulted in overt expression of Nkx2-2, Nkx2-9, and Sox1 at day 3 (Figure 2F). In contrast to ES cells, where PRC1 loss also caused an up-regulation of downstream hematopoietic regulators (such as Scl, Runx1, and Fli; supplemental Figure 3E top panel), expression of these genes by hemangioblasts was unaffected by PRC1 withdrawal (supplemental Figure 3E bottom panel). Taken together, these data show that there is extensive remodeling of lineage-appropriate genes upon mesoderm commitment, yet several lineage-inappropriate genes capable of executing an alternative fate remain bivalent and primed for expression. Ring1b-depleted Flk1+ hemangioblasts were unable to generate hematopoietic colonies (Figure 2G), a defect that was evident after a single day of tamoxifen treatment (supplemental Figure 3F), confirming the importance of PRC1 in the proliferation and differentiation of stem cells.24

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that many neural-specifying genes remain bivalently marked and functionally primed for expression in ES-derived committed hemangioblasts. These include Sox1, Nkx2-2, and Nkx2-9 (Figure 2A-B), Ngn1, Ngn2, and Msx1 (data not shown), and Math1, a gene that, although bivalent, showed a delayed timing of replication and insensitivity to PRC1 withdrawal on mesoderm induction. Collectively, these data suggest that hemangioblast precursors may be much more plastic than has previously been appreciated and argue that lineage restriction is probably not the result of an abrupt stage-specific loss of potential (as has been suggested20,25 ) but rather reflects a more gradual and progressive decline in accessibility of multiple lineage-inappropriate genes over time.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Haruhiko Koseki (RIKEN Institute, Japan) for the kind gift of Ring1a−/−/Ring1bfl/fl/Cre-ERT2 ES cells, Amanda Evans (Medical Research Council NIMR, United Kingdom) for technical assistance, and the Medical Research Council CSC flow cytometry facility for FACS.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council and Epigenome NoE Framework 6.

Authorship

Contribution: L.M., H.F.J., J.S.-R., and S.P. performed the experiments; L.M., H.F.J., M.M., and A.G.F. wrote the paper; and all authors designed the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for L.M. is Department of Experimental Oncology, European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy. The current affiliation for H.F.J. is Medical Research Council National Institute for Medical Research, London, United Kingdom.

Correspondence: Amanda G. Fisher, Medical Research Council Clinical Sciences Centre, Faculty of Medicine Imperial College London, Du Cane Rd, London W12 0NN, United Kingdom; e-mail: amanda.fisher@csc.mrc.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

L.M. and H.F.J. contributed equally to this study.