Abstract

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is classified into 3 clinical subsets: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficiency-associated BL. So far, possible differences in their gene expression profiles (GEPs) have not been investigated. We studied GEPs of BL subtypes, other B-cell lymphomas, and B lymphocytes; first, we found that BL is a unique molecular entity, distinct from other B-cell malignancies. Indeed, by unsupervised analysis all BLs clearly clustered apart of other lymphomas. Second, we found that BL subtypes presented slight differences in GEPs. Particularly, they differed for genes involved in cell cycle control, B-cell receptor signaling, and tumor necrosis factor/nuclear factor κB pathways. Notably, by reverse engineering, we found that endemic and sporadic BLs diverged for genes dependent on RBL2 activity. Furthermore, we found that all BLs were intimately related to germinal center cells, differing from them for molecules involved in cell proliferation, immune response, and signal transduction. Finally, to validate GEP, we applied immunohistochemistry to a large panel of cases and showed that RBL2 can cooperate with MYC in inducing a neoplastic phenotype in vitro and in vivo. In conclusion, our study provided substantial insights on the pathobiology of BLs, by offering novel evidences that may be relevant for its classification and possibly future treatment.

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is listed in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid tumors as a single genetic and morphologic entity with variable clinical presentation.1 In particular, the WHO classification recognizes 3 clinical subsets of BL: endemic (eBL), sporadic (sBL), and immunodeficiency-associated (ID-BL). Each affects different populations and can present with different features.

The endemic form is overall the commonest type, being the most frequent childhood cancer in equatorial Africa.1-4 eBL is almost invariably associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, although local environmental toxics (ie, Euphorbia tirucalli) and coinfection with arbovirus or, specially, malaria also appear to be important for its pathogenesis.5-7

sBL is the most commonly recorded form in the United States and Europe. As opposed to eBL, only ∼ 20% of cases are associated with EBV.8

Immunodeficiency-associated BL occurs more commonly in patients infected with HIV (HIV-BL) and rarely in patients who have undergone organ transplantation.9 Intriguingly, because HIV-BL can occur in patients with relatively high CD4 counts, immunnosuppression per se is not sufficient to explain the relatively high prevalence of BL in this setting.10,11 On clinical ground, the link between EBV and HIV-BL is less clear than for eBL.1,12,13

On the basis of morphology, phenotype, and genetics, BL is currently regarded as a germinal center (GC)–derived neoplasm.1 Nevertheless, according to the somatic hypermutation (SH) patterns and the expression of specific EBV-related molecules, in the WHO classification a different origin for the endemic and sporadic forms has been suggested.1,14,15

At genetics, BL molecular hallmark is the ectopic expression of the MYC oncogene, because of reciprocal chromosomal translocations, juxtaposing MYC to the immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH@) locus [(t(8;14)(q24;q32)] or the κ or λ light chain loci [(t(2;8)(p12;q24) and t(8;22)(q24;q11), respectively]. Interestingly, differences in the break point on chromosome 14 for the translocation of MYC to the IGH@ locus, as well as in the mutation pattern of the 5′-region of MYC, have been recorded between eBL and sBL.16 In addition, although all BLs have similar phenotype and MYC translocation, it has been argued that the 3 subtypes may have different pathogenetic mechanisms. In particular, because of the peculiar association patterns, a role for EBV has been proposed.15 However, there is still no satisfactory explanation of whether and how EBV participates in the pathogenesis of BLs, and it is probable that different (or multiple) environmental exposures may converge in a common pathogenetic mechanism.

Recently, 2 independent studies documented that sBL has a unique gene expression profile (GEP), distinct from those of other B non-Hodgkin lymphomas (B-NHLs) and, especially, that of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).17,18 However, no GEP study has included all BL subtypes so far.

In this study, we performed a gene expression analysis of eBL, sBL, and HIV-BL cases as well as of a large panel of B cell–derived malignancies and normal B-cell populations to (1) assess whether BL subtypes present with differences in their GEPs, (2) investigate the relationship of the different BL subtypes with the nonneoplastic cellular counterparts, and (3) identify genes and programs specifically deregulated in BLs and possibly contributing to the malignant phenotype.

Methods

Case selection

One hundred fifty-two B cell–derived malignancies and 20 samples of normal B-cell subpopulations were studied by GEP analysis. In particular, we studied 40 BL samples (13 eBLs, 21 sBLs 6 HIV-BLs), together with 40 follicular lymphomas (FLs), 10 chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) samples, 10 GC B-type DLBCL, 10 ABC-type DLBCL, 5 primary mediastinal B-cell lymphomas, 13 HIV-related DLBCL, and 34 marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs). In addition, we analyzed 20 samples of normal B-cell subpopulations, including GC (n = 10), naive (n = 5), and memory (n = 5) cells. Details on such cases are provided in supplemental File 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

All diagnoses were reviewed by ≥ 2 expert hematopathologists (S.A.P. and L.L.) and were formulated according to the WHO classification.1 All of the samples were obtained at the time of diagnosis, before treatment administration. The histopathologic characteristics of the 16 BL cases for which GEPs were generated are summarized in supplemental Table 1. Briefly, all cases were t(8;14)-positive, and the immunophenotype was consistent with the diagnosis (CD10+, CD20+, BCL6+, Ki67 > 98%, BCL2−). All cases but 2 HIV-BLs and the sBL were EBV+.

In addition, 356 cases were studied by immunohistochemistry for validation purposes (details are presented in Table 3 and supplemental File 1).

The study was approved by each institutional ethical committee, and written permission and informed consent have been obtained before sample collection in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In particular, this study is a part of an integrated project approved by the Italian government, involving the pathology departments of the University of Siena, the University of Bologna in Italy, and the Lacor Hospital (Gulu) and the Makerere University (Kampala) in Uganda, as well as other European institutions.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was extracted with the use of the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen and Life Technologies), purified with the use of the RNeasy Kit (QIAGEN), and processed according to the Affymetrix Expression Analysis Technical Manual. Fragmented cRNA (15 μg) was hybridized to HG-U133 2.0 Plus microarrays (Affymetrix). The gene expression values were determined by MAS 5 algorithm in Expression Console (Affymetrix), and normalization was performed by scaling to a target intensity of 500. Normalization quality control was performed by box-plot and MA plot consistency.

Gene expression analysis was carried out as previously reported.19,20 For details, see supplemental File 1.

Gene expression studies were conducted according to Minimum Information About a Microarray Experiment (MIAMI) guidelines. Raw gene expression data are available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo/ under accession number GSE26673.

Cell transfection and gene silencing

To evaluate the possible pathogenetic relevance of additional genomic events rather than MYC translocation in eBL, we generated an experimental model that was based on GEP results, by engineering a normal B-lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL; a kind gift of Prof A. Lanzavecchia, IRB Bellinzona, Switzerland). First, to mimic MYC ectopic expression, we induced MYC expression by transfection (pcDNA3-MYC), followed by antibiotic selection, as previously described.21 Selected clones, which showed high MYC expression, were then used for further genetic engineering. Second, we induced RBL2/p130 gene silencing to reproduce the functional consequences of mutations occurring in primary eBL cases.22,23 Such abnormality was chosen as an example of additional events as (1) consistently recurrent in eBL,22 (2) recently characterized by our group as functionally relevant ex vivo,23 (3) possible object of further investigation by a novel bioinformatic tool (Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks; ARACNe) involving a transcription factor (see “The proliferation signature of endemic BL relies on either MYC expression and other factors”), and (4) the RBL2 network, as inferred by ARACNe, being enriched in eBL signature (see “The proliferation signature of endemic BL relies on either MYC expression and other factors”). For details, see supplemental File 1.

Soft agar and invasion capability assays

Soft agar assays were performed as described with minor modifications,24 and invasion capability was then tested by CytoSelect 24-well Cell Invasion Assay, Basement Membrane on Colorimetric format (Cell Biolabs), according to the manufacturer's instruction. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times. Further details are provided in the supplemental File 1.

Xenografted mouse model for in vivo validation

Animal care and humane use and treatment of mice were in strict compliance with (1) institutional guidelines, (2) the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences, 1996), and (3) the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. In addition, specific consent was obtained from the Central Ethical Committee of the Italian government for all animal experiments.

Briefly, cells carrying both genetic alterations, which resulted to have transforming potential in vitro, were then tested for their capability of generating tumors in vivo. As a control, cells with only either MYC overexpressed or RBL2 silencing were used, as well as cells transfected with the empty vector and untransfected cells. Tumors were generated by the intraperitoneal injection of 10 × 106 cells into nude mice (Harlan). Tumor formation in mice was carefully monitored, and after 4 weeks mice were killed for pathologic assessments.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out with the StatView 5.0 software package (SAS Institute Inc). Differences in colony formation, Matrigel invasion, and tumor formation in mice were evaluated by 2-sided Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher exact test, or χ2 test when appropriate. The limit of significance for all analyses was defined as P < .05.

Results

BL has a relatively homogeneous molecular phenotype distinct from other B-cell malignancies

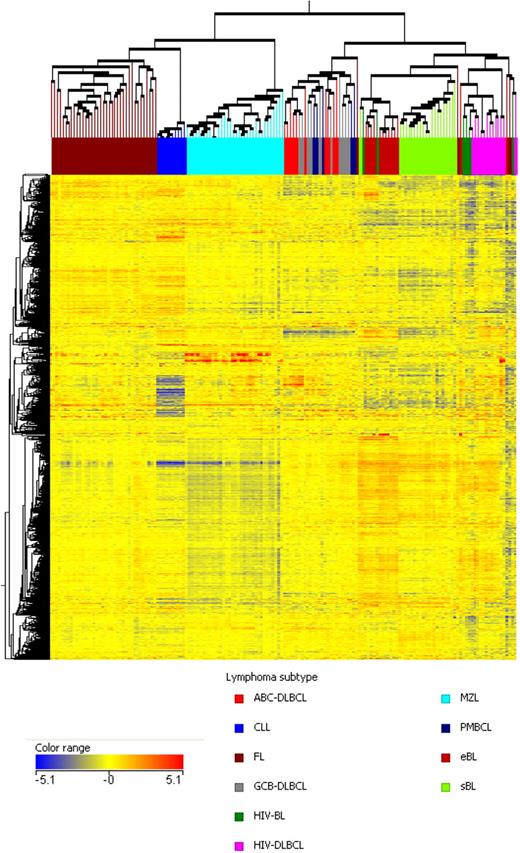

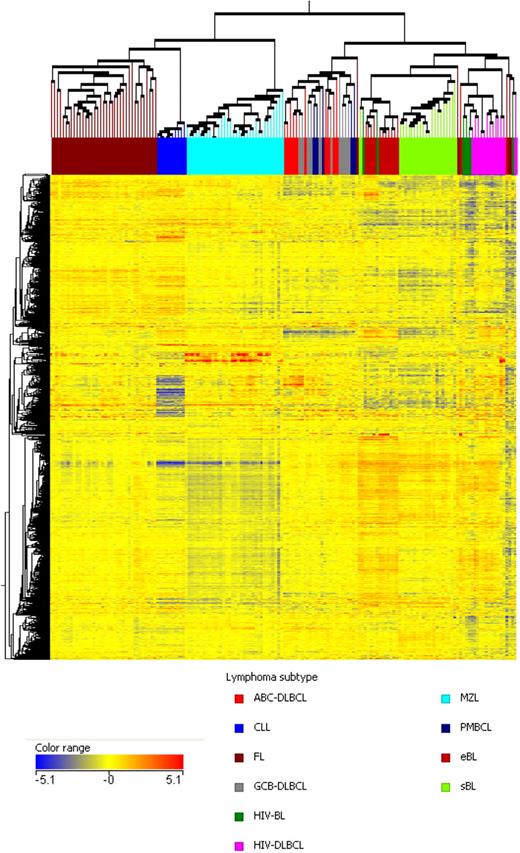

BL subtypes, at present, are defined only on the basis of clinical/epidemiologic features. To assess whether BLs have a homogeneous GEP, we tested by unsupervised analysis all BL subtypes (endemic, sporadic, and HIV) and a large panel of B cell–derived malignancies, including FL, DLBCL, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma, MZL, and CLL. First, we found that all BLs were grouped within one cluster, presenting with relatively homogeneous profiles (Figure 1). Interestingly, we also found that the GEPs of DLBCL originating in HIV+ patients were more intimately related to those of BLs (and, specially, eBL and HIV-BL) than to the other DLBCLs (Figure 1). Apparently, such intriguing phenomenon was not related to the EBV status. In fact, almost all HIV samples, both EBV+ and EBV−, clustered apart, close to BLs (Figure 1). However, HIV+ DLBCL cases showed a significant enrichment in MYC targets compared with HIV− cases.25 Thus, it is conceivable that a MYC-dependent signature had a major effect on the clustering, leading HIV+ DLBCLs close to BLs.

BL is a unique entity distinct from other B-cell malignancies. The unsupervised hierarchical clustering, based on the expression of the 9848 most informative genes, clearly separated the different diseases. In particular, eBL, sBL, and HIV-BL were grouped within a unique cluster. The dendrogram was generated with the use of a hierarchical clustering algorithm that was based on the average-linkage method. In the matrix, each column represents a sample and each row represents a gene. The color scale bar shows the relative gene expression changes normalized by the standard deviation (0 is the mean expression level of a given gene).

BL is a unique entity distinct from other B-cell malignancies. The unsupervised hierarchical clustering, based on the expression of the 9848 most informative genes, clearly separated the different diseases. In particular, eBL, sBL, and HIV-BL were grouped within a unique cluster. The dendrogram was generated with the use of a hierarchical clustering algorithm that was based on the average-linkage method. In the matrix, each column represents a sample and each row represents a gene. The color scale bar shows the relative gene expression changes normalized by the standard deviation (0 is the mean expression level of a given gene).

Second, we tested whether the recently described molecular signature distinguishing sBL from DLBCL17,26 was able to discriminate eBL and HIV-BL from DLBCL as well. Indeed, by applying a support vector machine algorithm for class prediction, 13 of 13 eBLs and 6 of 6 HIV-BLs were correctly identified as BLs (overall accuracy, 100%; Table 1).

Taken together, these results showed that BLs have a relatively homogeneous molecular profile, different from those of other B-NHLs, independently from the clinical setting.

BL subtypes present differences in their GEP

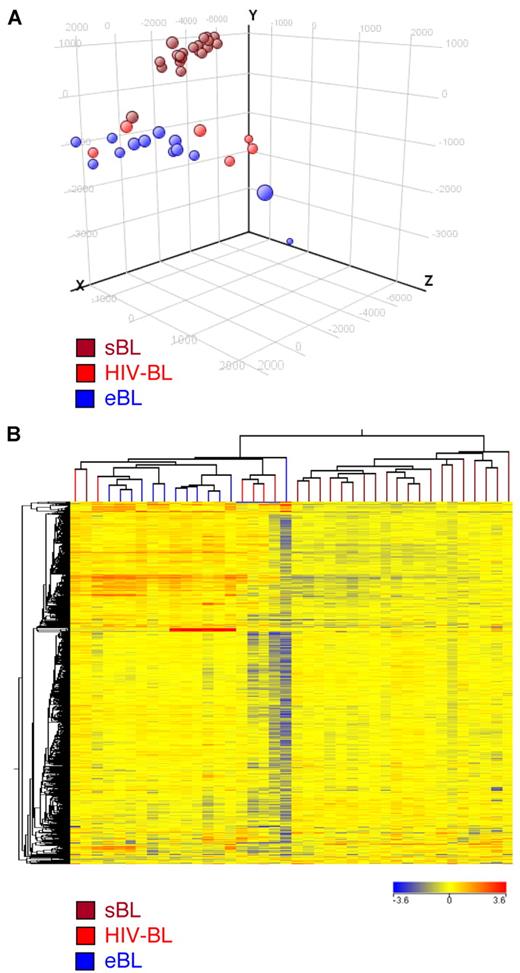

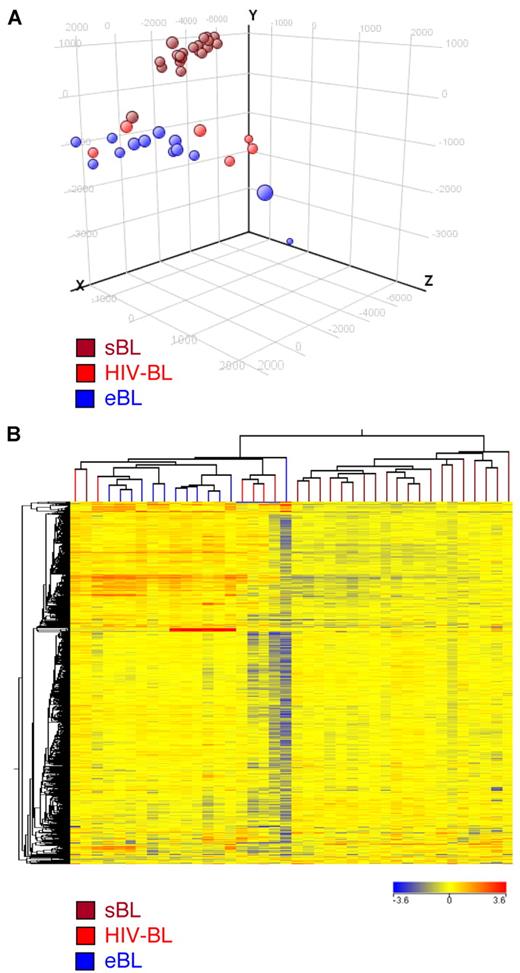

We then investigated whether BL subtypes can be differentiated according to their GEP. To address this issue, we directly compared the GEPs of eBL, sBL, and HIV-BL. First, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed that the 3 subtypes can be only roughly distinguished according to their GEPs. In particular, eBL and HIV-BL appeared to be strictly related, with quite similar molecular features, whereas sBL was relatively more distinct (Figure 2). Interestingly, HIV-BLs were close to eBLs independently to the EBV status. In fact, they all clustered with eBL (Figure 2), although 5 of 6 were EBV− (see supplemental Table 1 and Deffenbacher et al25 ).

BL subtypes present with differences in their GEPs. Both unsupervised analyses, principal component analysis (A) and hierarchical clustering (B), could discriminate the 3 different BL subtypes. Notably, eBL and HIV-BL appeared to be strictly related.

BL subtypes present with differences in their GEPs. Both unsupervised analyses, principal component analysis (A) and hierarchical clustering (B), could discriminate the 3 different BL subtypes. Notably, eBL and HIV-BL appeared to be strictly related.

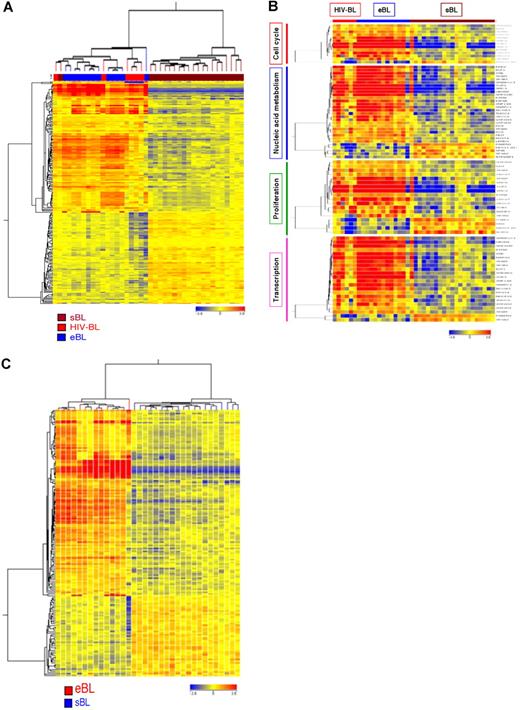

Subsequently, we performed a supervised comparison of the 3 groups (Kruskal-Wallis and analysis of variance tests, Bonferroni correction; P < .05). Two hundred twenty-two probe sets turned out to be differentially expressed among BL subtypes (Figure 3A). Interestingly, the genes differentially expressed among BL subtypes were enriched in functional categories such as proliferation, cell-cycle regulation, transcription, and nucleic acid metabolism (Figure 3B). In addition, by looking for specific pathways, we found B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)/nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) to be significantly overrepresented. More specifically, however, we found that eBL and HIV-BL had almost identical GEPs, with only a minimal set of genes differentially expressed (Figure 3A). Although the molecular signatures of eBL and sBL were overall similar, it was possible to identify 155 probe sets, corresponding to 129 unique genes, differentially expressed in the 2 groups with a fold change ≥ 2 (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 1). Notably, when we divided eBL and sBL in training and test sets (18 and 16 cases, respectively), we could identify a set of genes (N = 73) that to ones with maximal differences in expression in the 2 groups; by building a Support vector machines (SVM) model that was based on these 74 genes, we could correctly classify all the samples belonging to the test set as eBL or sBL (Table 2; supplemental Table 2). Similarly, these genes turned out to be differentially expressed in HIV-BL compared with sBL as well (not shown).

BL subtypes present with differences in their GEPs. (A) Supervised approach identified 222 probe sets differentially expressed in eBL versus sBL versus HIV-BL (Kruskal-Wallis test). (B) The corresponding genes belonged to relevant functional categories, including cell cycle regulation, nucleic acid metabolism, proliferation, and transcription. (C) Supervised analysis of eBL versus sBL identified 129 genes differentially expressed.

BL subtypes present with differences in their GEPs. (A) Supervised approach identified 222 probe sets differentially expressed in eBL versus sBL versus HIV-BL (Kruskal-Wallis test). (B) The corresponding genes belonged to relevant functional categories, including cell cycle regulation, nucleic acid metabolism, proliferation, and transcription. (C) Supervised analysis of eBL versus sBL identified 129 genes differentially expressed.

Interestingly, because it was recently proposed that 6 miRNAs are differentially expressed in eBL than in sBL (hsa-miR-191, hsa-miR-374a, hsa-miR-193a-5p, hsa-miR-10b, hsa-miR-216b, and hsa-miR-499-3p; H. Stein, personal communication, May 2010), we identified their putative targets by using the PicTar Web Interface (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de; supplemental Table 4). We then tested their expression in our panel by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA); we found that the eBL signature was significantly enriched in such molecules (P = .01). In addition, we found 10 of 18 supposed targets of miR-127 (supplemental Table 4) to be overexpressed in eBL cases. Notably, miR-127 has been recently shown to be altered in EBV+ BLs.27,28 Finally, by GSEA, we found only the above-mentioned miRNA targets to be significantly enriched in eBL compared with sBL, whereas none of the other categories included in the Broad Institute cytogenetic, functional, regulatory-motif, neighborhood, and Gene Ontology sets was enriched.

The proliferation signature of endemic BL relies on either MYC expression and other factors

Because we found that eBL and sBL differed for genes involved in cell cycle control, we investigated whether RBL2 abnormalities might contribute to the molecular profile of eBL cases. In fact, we recently suggested the possible role of RBL2, a tumor suppressor gene belonging to the retinoblastoma family and basically responsible for cell cycle control, in eBL pathogenesis.23 To address this issue, we first used a reverse engineering algorithm (ARACNe) to identify genes whose mRNA expression is directly correlated with RBL2 activity in a set of GEPs obtained from both normal B cells and a subset of B cell–derived tumors.19,29 The ARACNe-predicted RBL2 network included 655 genes (supplemental Table 5). We then tested whether the genes differentially expressed in eBL compared with GC B cells were enriched in RBL2-related genes, and we found a significant overlap between the 2 signatures (P < .0001). As control, we first repeated the experiment by using the MYC network inferred with the use of the same ARACNe algorithm and recently described by Basso et al.19 Indeed, as expected, the eBL signature was enriched in molecules identified by ARACNe as MYC network genes (P < .0001). Moreover, because both MYC and RBL2 regulate proliferation, we tested whether the RBL2 network depleted of the genes possibly belonging to both networks was still significantly represented in the eBL signature. Indeed, the enrichment was still significant (P = .0003).

Subsequently, we tested whether eBL was enriched in RBL2 network genes in comparison to sBL. Indeed, GSEA showed a significant enrichment of such molecules in eBLs (P = .0003).

Finally, to further test the specificity of our result, we also checked a gene list representing a generic cyclin/cell cycle regulation pathway (and including RB family genes),30 and we did not find any significant enrichment in eBL signature (neither vs GC cells nor vs sBL). Taken together, these results underline the role of additional events in eBL pathogenesis, proposing RBL2 as tumor suppressor in this contest.

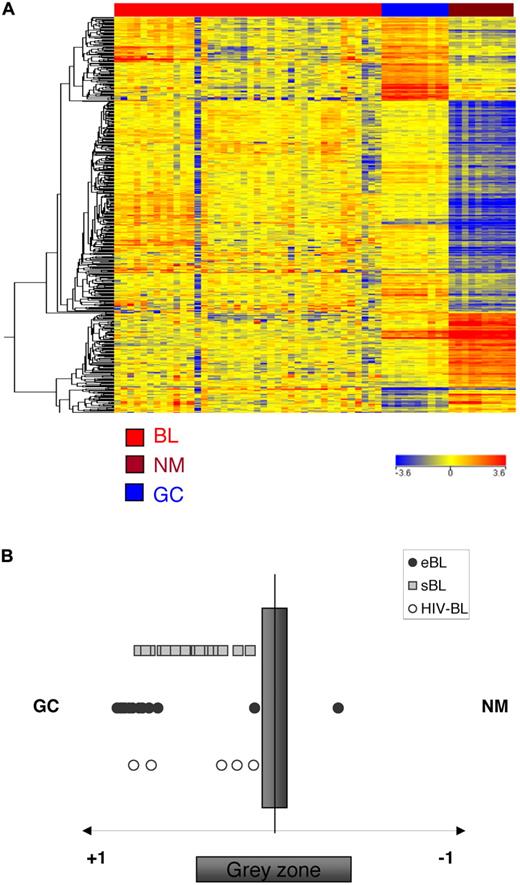

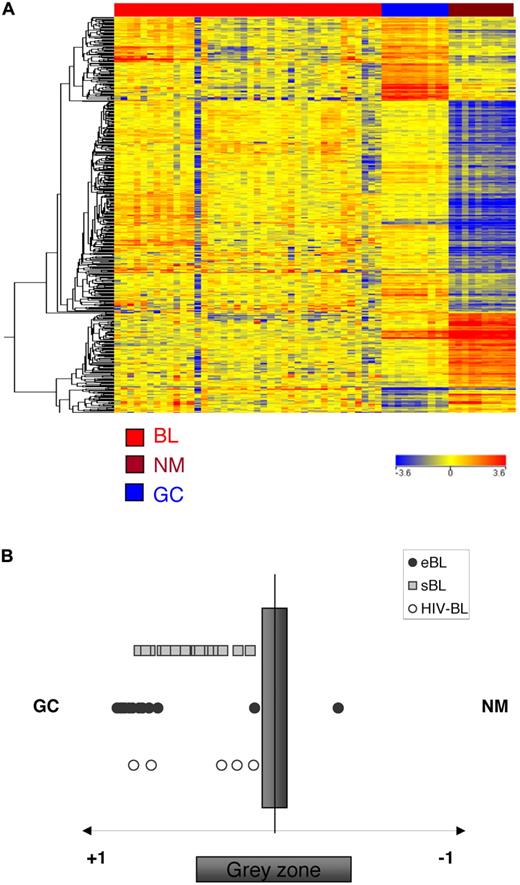

BL is closely related to GC cells

GC cells are currently considered the normal counterpart of BL. However, on the basis of patterns in the IGH@ genes14 and peculiar EBV-related molecule expression, the WHO classification could not univocally recognize eBL origin, and even post-GC derivation has not been excluded.1 To better understand the relationship between BL subtypes and normal B cells, we first applied an unsupervised approach and found that all BL cases clustered within one group, being clearly distinct from normal B cells (Figure 4A). Subsequently, we analyzed BLs for the expression of genes that are differentially expressed in purified tonsillar GC (centroblasts and centrocytes) versus non-GC B cells (naive and memory), as defined previously by supervised analysis.20,31,32 The analysis indicated that the BL cases are significantly more related to GC B cells than to memory and naive B cells (Figure 4B), independently from the clinical subtype (ie, endemic vs sporadic vs HIV-related). Similarly, by applying a support vector machine algorithm for class prediction that was based on the above-mentioned signature, all but 2 BL cases (1 eBL and 1 HIV-BL) appeared to be more related to GC cells (supplemental Table 6). Finally, GSEA was applied to assess whether eBL cases present with possible enrichment in post-GC programs; however, no significant enrichment was recorded as far as memory cells, plasma cells, or post-GC NHL (CLL and MZL) signatures are concerned. Taken together, our results indicate that all the different BL subtypes present with a molecular profile related to that of GC cells.

Relatedness of the GEP of BL to normal B-cell populations. Analysis of genes associated in normal B cells to the GC transitions in BL. The genes that are differentially expressed in naive, memory, and GC B cells during the GC transit were identified by supervised analysis. The expression of the transition genes is investigated in BL. All BL cases are more related to GC B cells than to naive/memory cells, irrespectively of the clinical subtype (A). A cell-type classification is used to measure the relatedness of BLs to naive/memory (NM) and germinal center (GC) B cells. The gray area marks 95% of confidence; the P value decreases with increasing distance from the x-axis (B).

Relatedness of the GEP of BL to normal B-cell populations. Analysis of genes associated in normal B cells to the GC transitions in BL. The genes that are differentially expressed in naive, memory, and GC B cells during the GC transit were identified by supervised analysis. The expression of the transition genes is investigated in BL. All BL cases are more related to GC B cells than to naive/memory cells, irrespectively of the clinical subtype (A). A cell-type classification is used to measure the relatedness of BLs to naive/memory (NM) and germinal center (GC) B cells. The gray area marks 95% of confidence; the P value decreases with increasing distance from the x-axis (B).

BLs differ from GC cells for the expression of molecules involved in proliferation immune response and BCR signaling

To identify genes and cellular programs altered as a consequence of malignant transformation, we performed a supervised comparison of BLs and normal GC B cells. In particular, we identified 1956 probe sets, corresponding to 1331 genes differentially expressed by the 2 groups (BL subtypes vs normal samples; Figure 5; supplemental Table 7). Specifically, 811 turned out to be down-regulated and 520 up-regulated in BL, respectively. Interestingly, such molecules corresponded to relevant biologic processes, according to gene ontology categories,33 some of which turned out to be significantly enriched in BL signature, such as cell proliferation, immune response/class II major histocompatibility complex antigen, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity, signal transduction, and others. In addition, among others, in BL we recorded higher expression levels of chemokines, transcription factors (including MYC, which served as internal control), and molecules involved in drug metabolism and interaction with microenvironment. However, among down-regulated genes, we found cell cycle regulators, surface molecules, chemokines and receptors, and genes involved in NF-κB pathway (for details, see supplemental Table 8).

Identification of genes differentially expressed in BL and normal GC B lymphocytes. Supervised analysis was performed with the use of 40 BL samples versus the 10 normal GC B-cell samples identified as the closest normal counterparts. The analysis identified 1956 probe sets (1331 genes) that are differentially expressed in BLs versus normal samples (supplemental Table 6).

Identification of genes differentially expressed in BL and normal GC B lymphocytes. Supervised analysis was performed with the use of 40 BL samples versus the 10 normal GC B-cell samples identified as the closest normal counterparts. The analysis identified 1956 probe sets (1331 genes) that are differentially expressed in BLs versus normal samples (supplemental Table 6).

To better understand the functional consequences of gene deregulation in BL, we investigated whether certain pathways were specifically affected. Importantly, the signature characterizing BL presented with a significant enrichment in molecules participating to BCR, TNFα/NF-κB, and NOTCH signaling, as well as intracellular cascade secondary to interleukin stimulation.

When the analysis was performed by dividing BL cases into training (N = 20) and test (N = 20) sets, analog results were obtained, and a cell classifier easily recognized BLs as tumor samples (supplemental Figure 2).

MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing affect cell proliferation

To validate the GEP findings, we aimed to assess the possible contribution of RBL2 abnormalities in eBL pathogenesis by functional in vitro and in vivo assays. First, we focused on the effects of its silencing, which mimics RBL2 point mutations occurring in eBL.15,22,23 Thus, we engineered EBV+ B cells to either overexpress MYC or silence RBL2. The latter was obtained with the use of 2 different short hairpin RNA directed against RBL2 (4 and 9), which induced equivalent silencing. Thus, for simplicity, only results relative to clones expressing sh4 are presented. Stable transfectants were then checked by immunofluorescence (supplemental Figure 3). Because these 2 genes affect cell proliferation, the proliferation rate of our clones was checked by cell count, whereas cell cycle was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. As controls, cells stably expressing either MYC or short hairpin RNAs against RBL2, as well as empty vector-expressing cells, were used. As expected, both MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing led to an increase of the proliferation rate, their combination conferring the highest advantage (supplemental Figure 4). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was then performed to monitor cell cycle. Our results confirmed that MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing cooperate in accelerating cell proliferation, because the G2/M cell population significantly increased in double transfectants (supplementary Figure 5).23 Intriguingly, in the same cell population a reduction of the number of apoptotic cells was observed, which is in line with the proapoptotic role of RBL2/p130 (supplemental Figure 5).

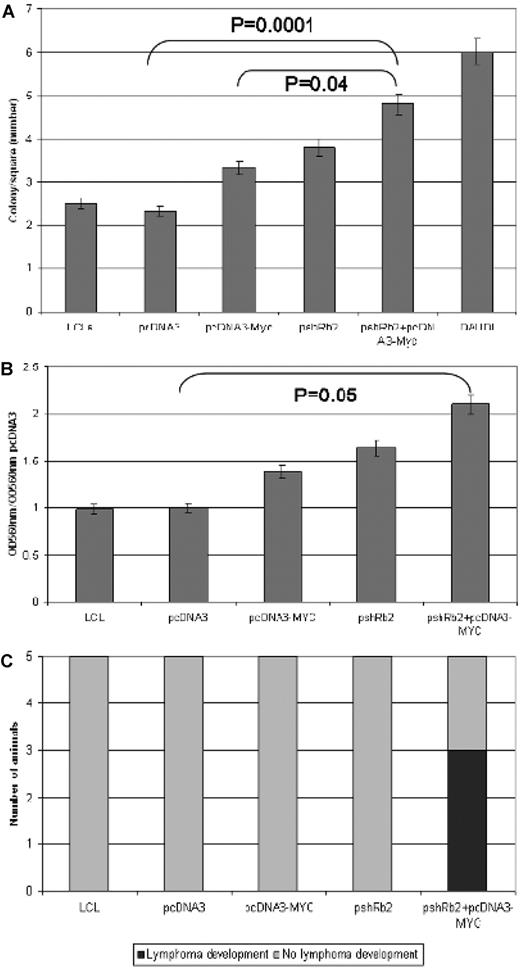

Effects of MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing on the tumorigenic potential of LCL cells in vitro

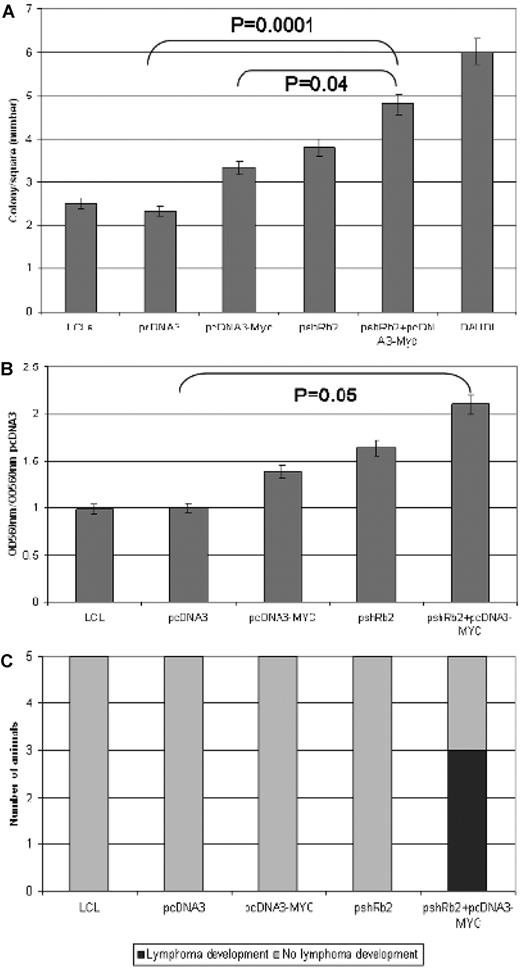

The neoplastic properties of the LCL cells engineered to carry either MYC overexpression or RBL2 silencing or both were then assessed by testing their ability to form colonies in soft agar. In this anchorage-independent growth test, we found that the colony-forming potential of double transfectants (pshRb2 + pcDNA3-MYC) was significantly higher than those of single transfectants (pshRb2 and pcDNA3-MYC, respectively; P = .004) as well as of mock-transfected cells (pcDNA3; P = .0001). In particular, the number of colonies was increased 43%, 64%, and 107% after pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, and pshRb2 + pcDNA3-MYC transfection, respectively (Figure 6A)

RBL2 silencing contributes to cell cycle deregulation in vitro and in vivo. (A) Soft agar assay: Comparison between the ability of empty vector–transfected cells and pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, or double-transfected cells to growth in soft agar. Error bars represent standard deviation between triplicates. In double transfectants, we observed significantly higher colony numbers than in single ones (P = .04). (B) Matrigel invasion assay: Comparison between the ability of empty vector–transfected cells and pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, or double-transfected cells to cross the extracellular matrix. Error bars represent standard deviation between triplicates. In double transfectants, significantly higher migration was detected (P = .05). (C) In vivo test indicated higher engraftment capability for double transfectants than for single ones.

RBL2 silencing contributes to cell cycle deregulation in vitro and in vivo. (A) Soft agar assay: Comparison between the ability of empty vector–transfected cells and pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, or double-transfected cells to growth in soft agar. Error bars represent standard deviation between triplicates. In double transfectants, we observed significantly higher colony numbers than in single ones (P = .04). (B) Matrigel invasion assay: Comparison between the ability of empty vector–transfected cells and pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, or double-transfected cells to cross the extracellular matrix. Error bars represent standard deviation between triplicates. In double transfectants, significantly higher migration was detected (P = .05). (C) In vivo test indicated higher engraftment capability for double transfectants than for single ones.

Effects of MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing on the invasion capability of LCL cells in vitro

Because double transfectants showed higher tumorigenicity in vitro compared with either single transfectants, to further investigate their transforming potential we tested whether they had increased capability to invade the extracellular matrix. We found that both RBL2 silencing and MYC overexpression confer the cells with the capability to cross the extracellular matrix (Figure 6B). However, in line with previous results, double transfectants turned out to be more aggressive than single ones as far as matrix invasion was concerned. In particular, cell migration was increased by 1.3-, 1.64-, and 2.1-fold after pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, and pshRb2 + pcDNA3-MYC transfection, respectively (P = .05; Figure 6B).

Intriguingly, we also observed that RBL2-silenced cells showed a slightly higher ability of digesting extracellular matrix, which may depend on the ability of RBL2/p130 to modulate the expression of proteins involved in cell adhesion (not shown).23

Effects of MYC overexpression and RBL2 silencing on the tumorigenic potential of LCL cells in vivo

To test the capability of the 3 transfectants (pcDNA3-MYC, pshRb2, and pshRb2 + pcDNA3-MYC) of generating tumors in vivo, we injected them into nude mice. Interestingly, tumor formation was observed only in animals receiving pshRb2 + pcDNA3-MYC cells. In particular, a bone marrow B-cell lymphoma developed in 3 of 5 experiments (Figure 6C). However, other sites such as the central nervous system, heart, spleen, liver, lymph nodes did not present with tumoral infiltration. According to morphology and phenotype, the tumor was classified as aggressive B-NHL because criteria for a clear BL diagnosis were not fulfilled.

Immunohistochemical validation on tissue microarrays

As further validation of GEP, to investigate whether the up-regulated mRNA levels of BL-associated genes corresponded to elevated levels of the encoded proteins, we stained tissue microarrays containing 85 BL cases (including the cases subjected to gene expression analysis) with the use of specific monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies raised against the selected molecules. In addition, we tried to assess whether the overexpression of these molecules was really because of the neoplastic cells or was perhaps secondary to reactive elements. In particular, we evaluated the expression of CYR61 and SPARC, because of their potential biologic relevance. We found CYR61 expressed in all BL cases (Table 3). Specifically, a positive staining was observed in neoplastic elements at both the cytoplasmic and nuclear levels. However, in normal lymphoid tissues, CYR61 was weakly expressed by scattered GC cells and by occasional mantle cells (Figure 7). In addition, we tested a panel of B-NHL (CLL, hairy cell leukemia, FL, and DLBCL) and found a proportion of cases to be CYR61+ within each entity (Table 3). However, a high degree of variability was observed in most instances. Furthermore, we studied SPARC and found it to be expressed in all BLs (Table 3). Indeed, intense cytoplasmic positivity was detected in virtually all neoplastic elements. Conversely, in reactive lymphoid tissues, SPARC expression was mainly confined to GCs where it stained macrophages and follicular dendritic cells and scattered lymphoid elements (Figure 7). Concerning other B-NHLs, a variable proportion of cases (slightly higher in GC-derived neoplasms) presented SPARC expression in tumor cells (Table 3).

Immunohistochemical analysis on tissue microarrays. Cases were considered as positive when > 30% cells were stained (Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with an Olympus UPlanFI × 40/075 or 20/050 numerical aperture objectives and Olympus CAMEDIA C-7070 camera; Olympus Italia Srl; magnification ×400; colors balanced after acquisition with Adobe Photoshop). BLs mainly consisted of neoplastic elements with typical morphology in the majority of cases (GIEMSA; GM). SPARC and CYR61 stainings are shown in BL and reactive lymph nodes (LNs). In both instances, nonneoplastic B cells were mostly negative, with scattered CYR61 positivities in GC and mantle (M) zones.

Immunohistochemical analysis on tissue microarrays. Cases were considered as positive when > 30% cells were stained (Olympus BX41 microscope equipped with an Olympus UPlanFI × 40/075 or 20/050 numerical aperture objectives and Olympus CAMEDIA C-7070 camera; Olympus Italia Srl; magnification ×400; colors balanced after acquisition with Adobe Photoshop). BLs mainly consisted of neoplastic elements with typical morphology in the majority of cases (GIEMSA; GM). SPARC and CYR61 stainings are shown in BL and reactive lymph nodes (LNs). In both instances, nonneoplastic B cells were mostly negative, with scattered CYR61 positivities in GC and mantle (M) zones.

Discussion

Here, we studied for the first time the GEPs of all BL subtypes and compared them with those of a large panel of B cell–derived malignancies and normal B lymphocytes. First, we showed that BL is a distinct entity, supporting the current WHO classification.1 In fact, we showed that the GEP of all BL subtypes is quite homogeneous and distinct from those of other lymphomas. In addition, importantly, we showed that the recently described BL molecular signature can effectively distinguish not only sBL but also eBL and HIV-BL from DLBCL.

However, it has been questioned whether the different BL subtypes, being characterized by peculiar epidemiologic and clinical features, may as well differ in cellular biology and pathogenetic mechanism. Interestingly, we found that eBL and HIV-BL had almost identical GEPs, whereas sBL cases were relatively more different. Of note, differences between eBL and sBL regarding significant pathways such as BCR, TNFα/NF-κB, and interleukin-dependent intracellular cascades, possibly reflect the different clinical contests. In fact, because eBL is known to have an onset in a contest of chronic antigen stimulation (in primis EBV, malaria, and arbovirus infections),5 it was not surprising that its molecular signature included many genes involved in immune response regulation. Similar considerations can be then applied to HIV-BL. However, whether the specific effects of EBV rather than the ongoing antigenic stimulation (or a polyclonal stimulation by superantigens) can be more relevant remain to be assessed. Intriguingly, among the genes differentially expressed in eBL and sBL (ie, bona fide, EBV+ and EBV− cases), we found 10 of 18 of the supposed targets of miR-127, the deregulation of which is a consequence of EBV integration,27,28 supporting the causative role of EBV in eBL development.5,15 However, it is notable that HIV-BL, which were collected in western countries, did behave as eBLs. In fact, not only are they known to be more similar to sBL at the genomic level, in terms of MYC/IGH@ breakpoint,16 but they were also mostly EBV−. Thus, it is conceivable that other factors (ie, chronic stimulation) might play a major role.

Interestingly, a significant difference between eBL and sBL also consisted in the enrichment in genes belonging to the RBL2 network, which we defined in a large panel of normal and neoplastic samples, with the use of a novel, quite effective bioinformatic tool for reverse engineering (ARACNe).19,29,34 Notably, RBL2 is mutated and not efficient in eBL,22,23 and, as further functional validation, we provided evidence that RBL2 silencing can cooperate with MYC overexpression in altering cell cycle control and invasion capability of EBV-infected cells. Thus, although MYC ectopic expression is sufficient for tumor initiation,35 the present data provided strong evidence of a consistent role for additional events in eBL full establishment and progression.

Furthermore, we showed that all BL subtypes are definitely related to GC B lymphocytes. In this regard, note that although sBL is currently regarded as a GC-derived tumor, the cellular origin of eBL has been largely questioned,1,14,15 and the histogenesis of eBL has not been defined in the present WHO classification.1 In particular, on the basis of EBV-related molecule expression and SH pattern, it has been suggested that eBL may derive from post-GC, memory B cells.1,14,15 Our data clearly showed that all BL molecular profiles were closer to those of GC lymphocytes than to those of memory cells. In addition, GSEA did not show any evidence of possible enrichment in either memory or plasma cell programs in eBL cells, whereas CD40 signaling appeared to be shut off (not shown), consistently with an early GC biology.19 In all, on the basis of morphology (medium-sized small centroblast-like cells),1 phenotype,1 genetics (ie, SH pattern and activation-induced cytidine deaminase–dependent MYC translocation occurrence),14,36,37 and global GEP, BL appears to correspond to an early GC cell. However, it cannot be ruled out that EBV+ tumors may derive from a later developmental stage, the differentiation arrest being because of miRNA deregulation induced by EBV itself.27,28

Subsequently, we defined a consistent set of genes differentially expressed in BL and normal GC cells, as a consequence of malignant transformation. Importantly, we found that relevant functional programs turned out to be altered, including those related to immune response, cell cycle regulation, and BCR signaling. As the latter is concerned, specifically, part of such differences may reflect either the differentiation arrest of BL neoplastic elements (ie, CB is substantially independent from BCR signaling),38 as well as be the consequence of the neoplastic transformation.

Finally, as further validation of gene expression data, immunohistochemistry was used to evaluate the expression of proteins corresponding to genes overexpressed in BL versus normal GC cells and according to potential biologic interest. Notably, both the tested molecules, CYR61 and SPARC, turned out to be strongly expressed by the neoplastic cells. This is of interest as such molecules may have a significant role in BL pathobiology. In fact, on the one hand, CYR61 expression has been related to malignant transformation in different settings, including human lymphomas, being also related to aggressive clinical behavior and drug resistance.20,39,40 On the other hand, SPARC contributes to the acquisition of migratory and invasive properties that are recapitulated by malignant tumor cells.41,42 In fact, evidence from SPARC-null in vitro and in vivo settings suggest that SPARC is able to directly affect NOTCH receptor signaling, thus determining the ability of cells to respond to key environmental signals involved in cell fate regulation, converging to the as–mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, which we found up-regulated in eBL despite a biased BCR signal initiation.43,44 Thus, the up-regulation of SPARC expression we observed in BL is in line with a cellular program oriented toward proliferation, migration, and extracellular matrix invasion, and that is poorly reliant on extracellular signals (also supported by major histocompatibility complex protein down-regulation). In BL, SPARC hyperexpression may represent a molecular hub linking together many of the cellular programs we found altered in BL, thus representing an appealing target for focused studies.45 Interestingly, in this setting, SPARC up-regulation might be sustained by MYC-driven miR-29–impaired expression.46 Importantly, normal GC cells mostly lacked SPARC/CYR61 expression; conversely, a proportion of B-NHL showed expression of the 2, highlighting their possible role in tumor development.

In conclusion, our study provided substantial insights on the pathobiology of eBL, by offering novel evidence that may be relevant for its classification and possibly future treatment. In fact, we clearly showed that all BL subtypes have a homogeneous GEP. In addition, we provided evidence that the molecular profile of BL subtypes is slightly, although significantly, different, suggesting different pathogenetic mechanisms and the role of infectious agents. Because the terms sporadic and endemic are exclusively based on epidemiologic basis, a better classification should take into account the causative pathogenetic mechanisms.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Riccardo Dalla Favera, Professor Ulf Klein, and Professor Katia Basso for gene expression data on normal B-cell generation and useful discussion; Dr Simona Righi for immunohistochemical staining; Dr Maria Antonella Laginestra for table editing; and Professor Maria Grazia Cusi for support in animal studies.

This work was supported by Centro Interdipartimentale per la Ricerca sul Cancro “G. Prodi.” BolognAIL, AIRC (IG4987, IG10007, and 5xMille), RFO (S.A.P. and P.P.P.), Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio in Bologna, Fondazione della Banca del Monte e Ravenna, Progetto Strategico di Ateneo 2006 (S.A.P. and P.P.P.), and Fondazione Monte dei Paschi di Siena.

Authorship

Contribution: G.D.F. and P.P.P. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; C.T., A.O., E.L., A.G., and M.R.S. performed research; C.A., C.B., S.L., S.F., and A.A. analyzed data; V.C., M.M., M.O., and L.T. contributed vital analytical tools; A.C. and M.K. performed research and analyzed data; L.L. and S.A.P. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pier Paolo Piccaluga, Molecular Pathology Laboratory, Haematopathology Unit, Department of Haematology and Oncology “L. and A. Seràgnoli,” S. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, University of Bologna, Via Massarenti, 9-40138 Bologna, Italy; e-mail: pierpaolo.piccaluga@unibo.it.

References

Author notes

P.P.P. and G.D.F. contributed equally to this study.

S.A.P. and L.L. contributed equally to this study.