To the editor:

Combination of conventional chemotherapy and the anti-CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody rituximab has become the standard of care for treating B-cell malignancies.1,2 Whereas the precise mechanisms of action of rituximab in vivo remain ill-defined, its effectiveness likely involves complement- and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity.3 Bezombes et al reported that acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase) and its product ceramide may mediate the growth inhibitory effect of rituximab on malignant B cells.4 aSMase is a hydrolase, encoded by the SMPD1 gene, which cleaves the ubiquitous phospholipid sphingomyelin to release ceramide.5 This lipid has emerged as a bioactive molecule that modulates membrane properties and the response of cancer cells to a variety of insults, including classic chemotherapeutic agents.5,6 Bezombes et al suggested that the generation of ceramide in lymphoma and B-CLL cells treated with rituximab occurred through aSMase; both ceramide and aSMase colocalized with CD20 at the cell surface. These events were proposed to mediate the in vitro growth inhibition.4 Intriguingly, rituximab was reported to interact with a peptide derived from a protein sharing homology with aSMase, suggesting that rituximab may bind to this enzyme.7 Whether such a function of aSMase in the response to rituximab translates to the in vivo situation in patients with lymphoma was unknown.

We had the unique opportunity to investigate the role of aSMase in an adult male patient with genetic aSMase deficiency who developed a marginal zone lymphoma at age 65. After 5 cycles of a combination of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone, splenomegaly was still present, leading to treatment interruption and splenectomy. Unexpectedly, microscopic examination of the spleen revealed no lymphoma cells but foamy cells suggestive of an inherited lipid storage disorder. Deficient aSMase activity was demonstrated by enzyme studies on peripheral leukocytes (0.14 vs 0.61 nmol/h/mg protein in controls), spleen (0.03 vs 0.68 nmol/h/mg) and EBV-transformed lymphoid cells (0.22 vs 2.6 nmol/h/mg). Diagnosis of Niemann-Pick disease (NPD; type B) was further confirmed by documenting sphingomyelin storage in spleen (389 vs 52 nmol/mg in controls) and identification of 2 point mutations in the SMPD1 gene (c.551C>T, p.P184L and c.733G>A, p.G245S), which have already been described in patients with NPD type B.8,9 Thus, despite aSMase deficiency, the patient efficiently responded to rituximab combined with chemotherapy. No relapse was observed 24 months after treatment initiation.

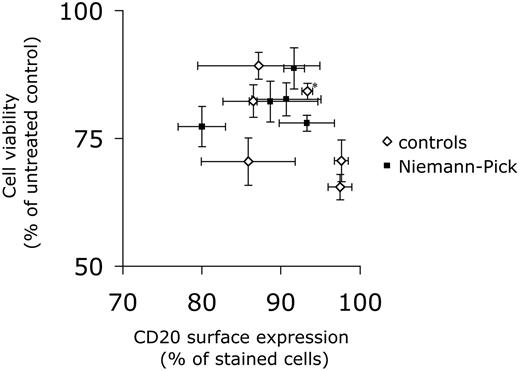

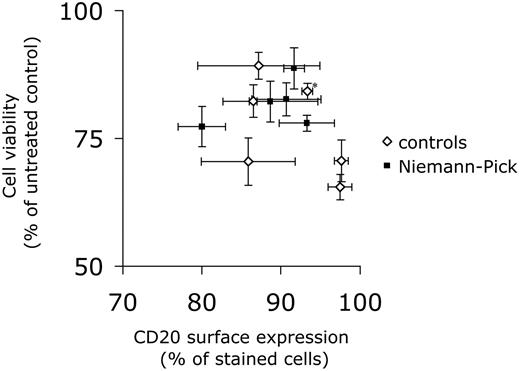

We then wanted to assess the in vitro response of NPD B cells to rituximab. As fresh lymphoma cells from the patient were not available, EBV-transformed lymphoid cells from the patient, as well as from other patients with NPD type A or B, and from control individuals, were tested. As illustrated in Figure 1, aSMase-deficient cells were equally sensitive to the antiproliferative effects of rituximab (and the chemotherapeutic agents used; not shown).

Sensitivity of control and Niemann-Pick disease cells to rituximab. EBV-transformed lymphoid cells from NPD patients (including the patient herein described, a patient with NPD type A and 3 patients with NPD type B) and from 6 control subjects (including a cell line from one of the NPD type B patients that had been corrected by retroviral transfer of the SMPD1 cDNA; denoted with an asterisk) were incubated for 72 hours with rituximab (10 μg/mL). Cell viability was assessed by the MTT test and is expressed as a function of cell-surface expression of CD20, as determined by flow cytometry. Data are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent determinations. Similar results were obtained in the presence of non-decomplemented serum (not shown). In addition, analysis of cell cycle by flow cytometry revealed a slight increase in the sub-G1 population both in control and NPD cells treated with rituximab (not shown).

Sensitivity of control and Niemann-Pick disease cells to rituximab. EBV-transformed lymphoid cells from NPD patients (including the patient herein described, a patient with NPD type A and 3 patients with NPD type B) and from 6 control subjects (including a cell line from one of the NPD type B patients that had been corrected by retroviral transfer of the SMPD1 cDNA; denoted with an asterisk) were incubated for 72 hours with rituximab (10 μg/mL). Cell viability was assessed by the MTT test and is expressed as a function of cell-surface expression of CD20, as determined by flow cytometry. Data are means ± SEM of at least 3 independent determinations. Similar results were obtained in the presence of non-decomplemented serum (not shown). In addition, analysis of cell cycle by flow cytometry revealed a slight increase in the sub-G1 population both in control and NPD cells treated with rituximab (not shown).

Therefore, this case report suggests that aSMase is dispensable for rituximab efficacy. If not fortuitous, the association of lymphoma and NPD would be reminiscent of the increased risk of malignancies seen in patients with Gaucher disease,10 another lipid storage disorder, thus pointing to the possible role of aSMase deficiency in cancer development.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: The authors thank E. Letrionnaire, S. Carpentier, M. Cortèse, E. Tournier, and B. Payre for technical assistance.

Contribution: F.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and reviewed the paper; J.S., L.A. and M.B.D. analyzed materials and data, and reviewed the manuscript; C.L. and P.B. contributed vital materials and reviewed the paper; J.C. reviewed the data, and wrote the manuscript; N.T. performed the research and analyzed data; N.A.A. and B.S. designed the research and reviewed the paper; C.R. provided clinical management, contributed vital materials, reviewed the data and the paper; and T.L. designed the overall study, analyzed data, and wrote the article.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thierry Levade, MD, PhD, Inserm UMR 1037, Centre de Recherche en Cancérologie de Toulouse, CHU Rangueil, BP 84225, 31432 Toulouse cedex 4, France; e-mail: thierry.levade@inserm.fr.