Abstract

Presently, blood transfusion products (TPs) are composed of terminally differentiated cells with a finite life span. We have developed an ex vivo–generated TP composed of erythroid progenitor cells (EPCs) and precursors cells. Several histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs) were used in vitro to promote the preferential differentiation of cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells to EPCs. A combination of cytokines and valproic acid (VPA): (1) promoted the greatest degree of EPC expansion, (2) led to the generation of EPCs which were capable of differentiating into the various stages of erythroid development, (3) led to epigenetic modifications (increased H3 acetylation) of promoters for erythroid-specific genes, which resulted in the acquisition of a gene expression pattern characteristic of primitive erythroid cells, and (4) promoted the generation of a TP that when infused into NOD/SCID mice produced mature RBCs containing both human adult and fetal globins as well Rh blood group Ag which persisted for 3 weeks and the retention of human EPCs and erythroid precursor cells within the BM of recipient mice. This ex vivo–generated EPC-TP likely represents a paradigm shift in transfusion medicine because of its potential to continue to generate additional RBCs after its infusion.

Introduction

Cord blood (CB) cells are an effective source of pluripotent hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCs/HPCs) that can be used to hematologically reconstitute patients who have received myeloablative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy.1 Numerous investigators have tried to increase CB stem cell numbers by culturing CD34+ cells ex vivo under a variety of culture conditions; these attempts have, however, met with limited success.2-13 CB-HSCs/HPCs have also been used to generate alternative sources of terminally differentiated blood cells for use as transfusion products.4,8 Adult blood HSCs/HPCs, human embryonic stem cells (ES) as well as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) have also been used for this same purpose.4,8,14,15

All presently available TPs are composed of terminally differentiated cells with a finite life span.2,4,8 HPCs retain their capacity to undergo repeated divisions allowing them to produce greater numbers of blood cells belonging to a particular lineage. The use of HPCs as a TP would represent a major paradigm shift because they would continue to generate differentiated cells for a prolonged period of time. The major obstacle to the creation of such a TP is the lack of sufficient numbers of HSCs/HPCs from a readily accessible sources.16-18 Recently, a variety of epigenetic events including the methylation of gene promoter regions as well as transcriptional inhibitory complexes such as histone deacetylases and certain histone methylases have been shown to influence HSC fate decisions.19,20 Chromatin-modifying agents (CMAs) such as HDACIs and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTIs) comprise a structurally diverse group of compounds which are capable of regulating chromatin remodeling and influencing gene expression patterns.21,22 Our laboratory has sequentially treated both adult marrow and CB-CD34+ cells with a DNMTI followed by an HDACI in vitro resulting in an increase in the numbers of human marrow repopulating cells (MRCs).23,24 The use of such small molecules to alter normal HSC/HPC fate decisions has been confirmed by several additional laboratories.13,19,25-27 We hypothesize that a particular combination of cytokines and an HDACI might be useful to promote erythroid commitment of CB-CD34+ cells.

Methods

Isolation of CB-CD34+ cells

Fresh CB collections were obtained from the Placental Blood Program at the New York Blood Center (New York, NY) according to guidelines established by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. Low-density CB-mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated by density centrifugation and CD34+ cells were isolated as previously described.23 Highly purified CB-CD34+ cells (90%-98%) were used for all experiments.

Ex vivo culture

Human CB-CD34+ cells (1 × 105/mL) were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Lonza) containing 30% FBS (HyClone Laboratories) supplemented with 100 ng/mL SCF, 100 ng/mL Flt3 ligand (FL), 100 ng/mL Tpo, and 50 ng/mL IL-3 (cytokines were a gift of Amgen) and incubated in a humidified incubator maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 16 hours of incubation, cells were exposed to individual HDACIs (1nM trichostatin A [TSA], Sigma-Aldrich; 1μM suberolylanilide hydroxamic acid [SAHA], gift of Merck Pharmaceuticals) and 1mM valproic acid (VPA; Sigma-Aldrich) and the cultures were continued for a week. At the end of culture period, the numbers of viable cells were enumerated using the trypan blue exclusion method. Treatment with 5azaD alone and/or 5azaD+ HDACI were performed as described previously by Araki et al.23

Flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting

Cells were stained with anti–human CD34 monoclonal antibody (mAb) with a corresponding isotype-matched control mAb. 7AAD was added to exclude dead cells and cells were analyzed by FACS using a FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson). In some experiments, after 7 days of culture CD34+ cells were reisolated using a CD34+ cell isolation kit as described in “Ex vivo culture.” All mAbs were purchased from BD PharMingen and Cell Signaling Technology Inc.

Hematopoietic progenitor cell assays

Single-cell CD34+ cell assay

CB-CD34+ (day 0) or CD34+ cells reisolated using immunomagnetic cell separation methods from cultures containing cytokines alone (CA) or cytokines plus VPA-containing cultures were resuspended in IMDM containing 30% FBS supplemented with 100 ng/mL SCF, 50 ng/mL IL-3, and 4 U/mL Epo and deposited at a concentration of 0.6 cells into individual wells of a 96-well plate using methods previously described.28 Using an inverted microscope, wells were observed not to contain > 1 cell. Cells were then incubated in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 12 to 14 days of culture, colonies within each well were individually scored and classified. Plating efficiencies were calculated as the fraction of (BFU-E + CFU-mix + CFU-GM/number of cells plated) × 100.

RNA extraction and Q-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from primary CB-CD34+ cells, CD34+ reisolated from the expansion cultures in the presence of CA or cytokines plus VPA after 7 days of incubation. Total RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA by using oligo dT and Superscript III (Invitrogen), followed by RNase H digestion. The quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) assays were performed using SYBR Green (Molecular Probes) and Platinum Taq (Invitrogen) on the Realplex thermocycler (Eppendorf). The primer sequences used in the real-time PCR assays are provided in the supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). All experiments were performed in triplicate and a nontemplate control (lacking cDNA template) was included in each assay. Gapdh and Tubulin were used as internal standards.

Analysis of histone acetylation

CD34+ cells were fixed with formaldehyde (2.8%) for 10 minutes at 37°C, briefly chilled on ice and permeabilized with 100% ice-cold methanol. Cells were incubated further on ice for 20 minutes and were blocked with incubation buffer (PBS containing 0.5% BSA) for 10 minutes and stained with H3lys9 FITC-conjugated mAb or an isotype control for an hour at room temperature. Cells were washed and analyzed by FACS.

ChIP assay

Potential transcription factors binding sites of the 1000-bp upstream regions of the genes of interest were analyzed using TFSEARCH (http://www.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html) using a default minimum cutoff score of 85 points. Primers were designed for the regions within binding sites of erythroid lineage–specific transcription factors with the highest scores. To examine H3 modifications, we used antibodies specific for acetylated H3K9/14 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), H3K27 (Millipore), and total histone H3 (Abcam). Micro-ChIP assays were performed as described by Dahl and Collas.29 CD34+ cells (2 × 106 to 4 × 106) were reisolated from cultures after 7 days of incubation23 washed in the presence of PBS/Na-butyrate (5mM) and fixed with formaldehyde. Cells were quenched with glycine and these cells were lysed and sonicated in a batch of 2 × 106 cells/sample using a bioruptor sonicator (Diagenode).

After sonication chromatin (with an average length of 500-bp DNA fragment) was aliquoted into 200-μL samples and immunoprecipitated using ChIP grade antibodies with an appropriate control (no antibody). One chromatin sample was used as an input reference. Input DNA, a no antibody control DNA, and ChIP DNA were purified and further analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR by using SYBR green as described in “RNA extraction and Q-PCR.” ChIP primer sequences are provided in supplemental Table 2.

NOD/SCID mouse model

All animal studies were approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee. NOD/SCID mice and NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mice double homozygous for the SCID mutation and IL-2Rγ allelic mutation (γcnull) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Six- to 8-week-old mice were sublethally irradiated with ∼ 300 rad of total body radiation. Human type O+ RBCs (4 × 108) were injected intraperitoneally to block the reticulo-endothelial system as previously described by others.4 CB-CD34+ cells were treated with cytokines and 1mM VPA for a week and then cultured in the presence of SCF, Epo(4 U/mL), and IL-3 for an 2 additional days to promote further expansion of EPCs. Twenty-four hours after the delivery of the human type O+ red cells, the mice were injected with cultured cells (4.8 × 108/mouse) intraperitoneally. Each group contained 2-3 mice. Mice were treated with subcutaneous Epo (20 U/mouse) on alternate days. Five microliters of blood was drawn from each mouse at various time intervals from the tail vein. This blood was stained with nuclear laser dye styryl-75 (LDS) and several mAb specific to human blood cells. Mice were killed after 15 and 30 days and BM, peripheral blood (PB), and spleen cells were analyzed for the presence of hu-CD45, CD36, CD33, CD14, CD19, CD41, and GPA.

Analysis of mouse blood for globin gene transcripts levels using RT-PCR

Total cDNAs were synthesized from RNA isolated from transplanted mouse blood using an oligo(dT) primer (Promega) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCRs were performed for huγ-globin, β-globin, and RhD and mouse α-globin. The list of primers is provided in supplemental Table 3. Amplicons were resolved on a 1.8% agarose gel.30

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as either the mean ± SD or mean ± SE of varying numbers of individual experiments. The Student t test was used in experiments involving pairwise comparisons. P values ≤ .05 were considered significant.

Results

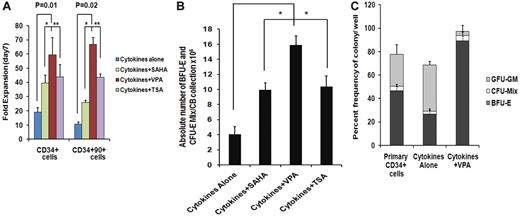

Effect of CMA on the ex vivo expansion of CB-CD34+ cells and assayable EPCs

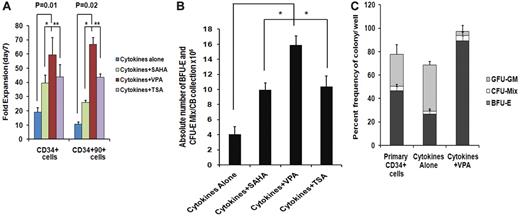

We have previously reported that treatment of adult and CB-CD34+ cells with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5azaD) followed by TSA promoted symmetrical HSC division in vitro leading to the expansion of the numbers of MRC.23,24 The ability of individual HDACIs including SAHA, TSA, and VPA at varying doses to promote the in vitro generation of assayable EPCs by CB-CD34+ cells was explored. The addition of each of the HDACIs promoted a greater degree of expansion of CD34+ and CD34+CD90+ cells compared with cells exposed to CA (Figure 1A). Cultures receiving CA experienced a 19.2- ± 3.0-fold increase in the number of CD34+ cells, while the addition of VPA resulted in the greatest degree of expansion of CD34+ cells (59.4- ± 12.1-fold, P = .01) compared with TSA (43.9- ± 8.4-fold, P = .02) and SAHA (39.5- ± 5.4-fold, P = .02). A 10.6- ± 1.3-fold expansion of the numbers of CD34+CD90+ cells was observed in the presence of CA, while the greatest fold expansion of CD34+CD90+ cells was also observed in the VPA-containing cultures (66.7- ± 4.7-fold, P = .02) compared with cultures containing TSA (43.6- ± 2.4-fold) or SAHA (25.9- ± 1.6-fold; Figure 1A).

Effect of chromatin-modifying agents on ex vivo expansion of CB-EPCs. (A) Effect of chromatin-modifying agents on ex vivo expansion of CB-CD34+: CD34+ cells were isolated from 5 individual CB units and treated with different HDACIs including SAHA (1μM), VPA(1mM), and TSA (1nM) and their effect on the number of CD34+ and CD34+CD90+cells following 7 days of culture was determined. The fold expansion of CD34+and CD34+CD90+ cell numbers was determined by dividing the total numbers of viable cells expressing the phenotype by the number of primary cells expressing the same phenotype multiplied by 100. A significant difference was observed between degree of expansion of CD34+cells (P = .01) and CD34+CD90+ cells (P = .02) obtained with VPA-containing cultures compared with cultures containing cytokines alone (n = 5). (B) Effect of HDACIs on the absolute number of BFU-E + CFU-Mix: CD34+ cells from 5 individual CB collections treated with cytokines and SAHA (1μM), VPA (1mM), or TSA (1nM) for 7days. The numbers of hematopoietic colonies were enumerated after 14 days. A greater number of BFU-E + CFU-Mix were generated in the presence of cytokines plus each of the HDACI (VPA, P = .002; SAHA, P = .04; and TSA, P = .08) compared with cultures containing cytokines alone. ■, BFU-E + CFU-Mix. (C) Effect of VPA on the fate of a single CD34+ cells: single primary CD34+cells and/or CD34+ isolated after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines alone and/or cytokines + VPA were deposited into 96-well plate in triplicate and supplemented with SCF, Epo, and IL-3. The number and types of HPC (BFU-E, CFU-Mix, and CFU-GM) were determined after 14 days of incubation (*P = .005; n = 3).

Effect of chromatin-modifying agents on ex vivo expansion of CB-EPCs. (A) Effect of chromatin-modifying agents on ex vivo expansion of CB-CD34+: CD34+ cells were isolated from 5 individual CB units and treated with different HDACIs including SAHA (1μM), VPA(1mM), and TSA (1nM) and their effect on the number of CD34+ and CD34+CD90+cells following 7 days of culture was determined. The fold expansion of CD34+and CD34+CD90+ cell numbers was determined by dividing the total numbers of viable cells expressing the phenotype by the number of primary cells expressing the same phenotype multiplied by 100. A significant difference was observed between degree of expansion of CD34+cells (P = .01) and CD34+CD90+ cells (P = .02) obtained with VPA-containing cultures compared with cultures containing cytokines alone (n = 5). (B) Effect of HDACIs on the absolute number of BFU-E + CFU-Mix: CD34+ cells from 5 individual CB collections treated with cytokines and SAHA (1μM), VPA (1mM), or TSA (1nM) for 7days. The numbers of hematopoietic colonies were enumerated after 14 days. A greater number of BFU-E + CFU-Mix were generated in the presence of cytokines plus each of the HDACI (VPA, P = .002; SAHA, P = .04; and TSA, P = .08) compared with cultures containing cytokines alone. ■, BFU-E + CFU-Mix. (C) Effect of VPA on the fate of a single CD34+ cells: single primary CD34+cells and/or CD34+ isolated after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines alone and/or cytokines + VPA were deposited into 96-well plate in triplicate and supplemented with SCF, Epo, and IL-3. The number and types of HPC (BFU-E, CFU-Mix, and CFU-GM) were determined after 14 days of incubation (*P = .005; n = 3).

We next evaluated the efficiency of equivalent numbers of primary CD34+ cells and cells expanded in the presence or absence of the individual HDACI to form hematopoietic colonies in vitro. The plating efficiency of cells exposed to CA was reduced by 50% compared with primary CB-CD34+ cells while the plating efficiency of cells exposed to cytokines and the various HDACIs were similar to that of the primary cells (Table 1). Furthermore, cells exposed to CA generated a lower percentage (30%) of EPCs (BFU-E and CFU-mix/total numbers of colonies × 100) than primary CB-CD34+ cells (39%). The potential for treatment with individual HDACIs to increase the absolute number of EPCs compared with a primary CB collection was then examined (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1B, the addition of VPA led to the generation of the greatest absolute number of EPC cells from single CB collections (14.9 × 106, P = .002), this represented an approximate 5500-fold increase in the number of assayable EPCs, compared with the primary CB collections and was greater than the number observed in cytokines plus SAHA (P = .04) or cytokines plus TSA (P = .08) containing cultures. The effects of sequential treatment with 5azaD alone or 5azaD followed by the addition of the various HDACIs on ex vivo expansion of CB-EPC was inferior to that observed with the corresponding HDACI alone (Figure 1B and supplemental Figure 1).

To determine whether VPA treatment altered the differentiation program of CB-CD34+ cells, an equal number (n = 300) of single primary CB-CD34+ cells (day 0) and a similar number of single CD34+ reisolated from ex vivo cultures treated with CA or cytokines plus VPA were analyzed for their ability to generate HPCs (Figure 1C). The plating efficiency of single primary CD34+ cells or CD34+ cells reisolated from cultures containing CA and single CD34+ cells exposed to cytokines plus VPA were 77.7%, 66.6%, and 94.6% (P = .003), respectively. The lineages of the HPCs present in these single-cell analyses dramatically differed. Approximately 50% of the HPC assayed from primary CB-CD34+ cells were EPCs while exposure to CA resulted in far fewer EPCs and a greater proportion of CFU-GM. By contrast, over 95% of the CD34+ cells reisolated from cultures treated with cytokines plus VPA were EPCs (P = .003; Figure 1C). These data indicate that the VPA preferentially promoted the decision of CD34+ cells to commit to the erythroid lineage.

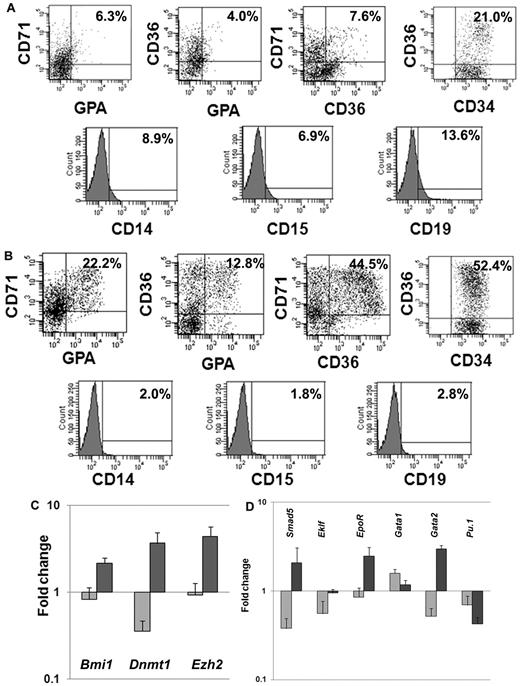

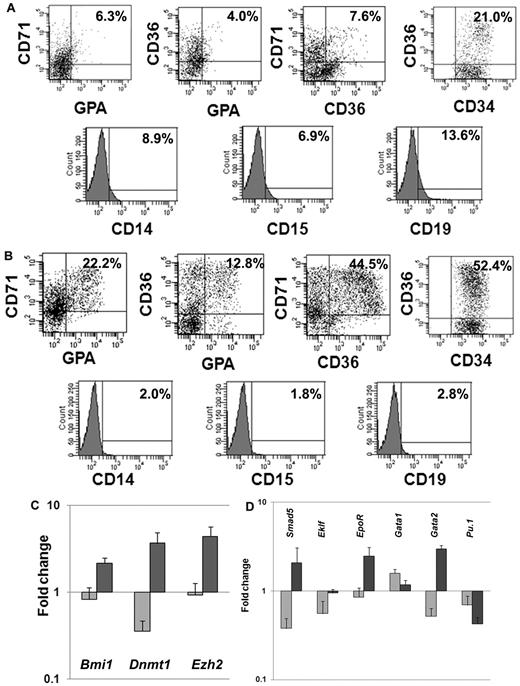

Phenotypic and molecular analyses of EPCs after ex vivo cell culture

We next investigated the expression of lineage-specific phenotypic markers expressed by CD34+ cells exposed to CA or cytokines plus VPA. We analyzed the expression of CD34 as well as 3 erythroid-specific markers, CD71, CD36, and glycophorin A (GPA). A significantly greater proportion of CD34+CD36+ (55.7% ± 4.7% vs 18% ± 4.2%; P = .01), CD36+CD71+ (51.3% ± 9.6% vs 8.5 ± 1.0, P = .02), CD36+GPA+ (15.4% ± 3.7% vs 5.5% ± 2.1%, P = .03) and CD71+GPA+ (25.6% ± 4.8% vs 6.1% ± 0.3%, P = .03) cells were observed in cultures with VPA plus cytokines compared with cultures containing CA. Furthermore, the VPA-treated cultures contained ∼ 6-fold fewer numbers of CD19+ (2.4% vs 14.3%) cells, 4-fold fewer numbers of CD14+ (1.9% vs 7.9%), and 3.6-fold fewer CD15+ (2.1% vs 7.7%) cells compared with cultures containing CA (Figure 2A-B).

Phenotypic and genetic analyses of hematopoietic cells after ex vivo cell culture. (A) Phenotypic analyses of VPA-treated CD34+ cells: CD34+ cells after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines alone or cytokines + VPA were analyzed by flow cytometrically. The expression of erythroid-specific markers (CD36, CD71, and GPA) and nonerythroid markers (CD14, CD15, and CD19) was assessed with appropriate lineage-specific monoclonal antibodies. For each mAb, the corresponding anti-isotype antibody was used in parallel to test the specificity of staining. Dot plots represent the percent expression of particular markers in day-7 cultures (n = 4, 1 of the 3 representative experiments is shown). (A) Cytokines alone; (B) cytokines + VPA. (C-D) Fold change in expression levels of genes associated with HSC/HPC and erythroid commitment: effects of VPA treatment on the relative transcript levels of genes (Dnmt1, Bmi1, Smad5, Ezh2, Eklf, EpoR, GATA1, GATA2, and Pu.1) was calculated by SYBR Green Q-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from primary CD34+ cells (day 0) and CD34+ cells isolated after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines with or without VPA treatment. GAPDH and tubulin was used as internal housekeeping genes. A relative mean normalized fold change in mRNA expression of VPA-treated CD34+ cells and CD34+ cells from cultures with cytokines alone were compared with the expression of these same genes in primary CB-CD34+ cells. Measurements were obtained in triplicate and a negative control (lacking the cDNA template) was included in each assay.  , cytokines alone;

, cytokines alone;  , cytokines + VPA (n = 4).

, cytokines + VPA (n = 4).

Phenotypic and genetic analyses of hematopoietic cells after ex vivo cell culture. (A) Phenotypic analyses of VPA-treated CD34+ cells: CD34+ cells after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines alone or cytokines + VPA were analyzed by flow cytometrically. The expression of erythroid-specific markers (CD36, CD71, and GPA) and nonerythroid markers (CD14, CD15, and CD19) was assessed with appropriate lineage-specific monoclonal antibodies. For each mAb, the corresponding anti-isotype antibody was used in parallel to test the specificity of staining. Dot plots represent the percent expression of particular markers in day-7 cultures (n = 4, 1 of the 3 representative experiments is shown). (A) Cytokines alone; (B) cytokines + VPA. (C-D) Fold change in expression levels of genes associated with HSC/HPC and erythroid commitment: effects of VPA treatment on the relative transcript levels of genes (Dnmt1, Bmi1, Smad5, Ezh2, Eklf, EpoR, GATA1, GATA2, and Pu.1) was calculated by SYBR Green Q-PCR. Total RNA was extracted from primary CD34+ cells (day 0) and CD34+ cells isolated after 7 days of culture in the presence of cytokines with or without VPA treatment. GAPDH and tubulin was used as internal housekeeping genes. A relative mean normalized fold change in mRNA expression of VPA-treated CD34+ cells and CD34+ cells from cultures with cytokines alone were compared with the expression of these same genes in primary CB-CD34+ cells. Measurements were obtained in triplicate and a negative control (lacking the cDNA template) was included in each assay.  , cytokines alone;

, cytokines alone;  , cytokines + VPA (n = 4).

, cytokines + VPA (n = 4).

HSC self-renewal and lineage commitment are dynamic, highly complex, and related processes. We monitored the relative expression of a group of genes characteristic of both primitive HPC and erythroid commitment (Bmi1, Dnmt1, Ezh2, Smad5, Eklf, Gata1,Gata2, EpoR, and Pu.1). Q-PCR was performed on CD34+ cells reisolated from cultures treated with CA or cytokines plus VPA and compared with primary CB-CD34+ cells. The expression of genes associated with retention of the biologic properties of the primitive HPCs were up-regulated (Bmi1 [2.6-fold, P = .01], Dnmt1 [10.3-fold, P = .01], and Ezh2 [4.8-fold, P = .004]) in the presence of VPA (Figure 2C), while the expression of these same genes was down-regulated in CD34+ cells exposed to CA. Furthermore, VPA-treated CD34+ cells, were characterized by up-regulation of Smad5 (6.2-fold, P = .004), Gata2 (3.7-fold, P = .0005), Eklf (1.7-fold, P = .008), and EpoR (2.9-fold, P = .006). Pu.1 (0.6-fold) and Gata1 (1.9-fold, P = .01) expression were down-regulated in both the population of cells. The molecular portrait of the VPA-treated CD34+ cells was consistent with a population of EPCs which retains an extensive proliferative potential.

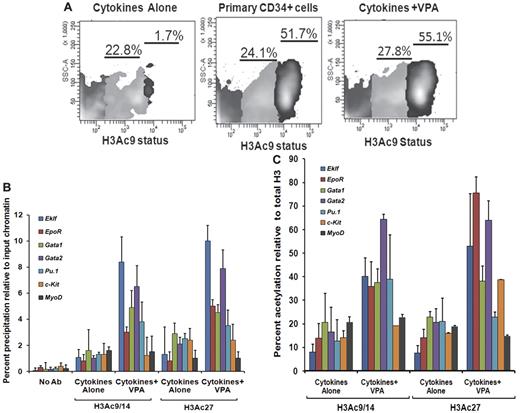

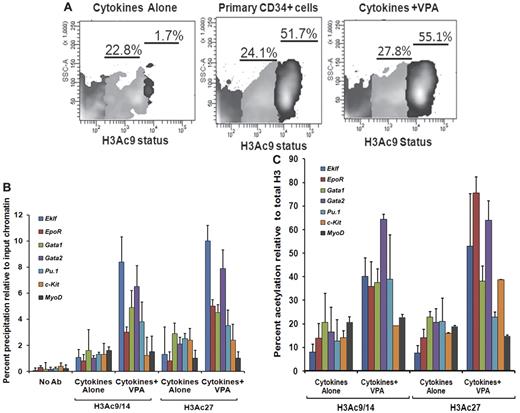

Histone H3 acetylation of HSCs/HPCs and promoter analyses of erythroid lineage–specific genes

We also investigated flow cytometrically, the H3 acetylation(AcH3K9) status of CD34+ cells reisolated from the VPA-treated cultures compared with CD34+ cells exposed to CA. Increased acetylation of H3K9 was observed in CD34+ cells after VPA treatment compared with CD34+ reisolated from cultures receiving CA. The CD34+ cells could be divided into 2 subpopulations based on the degree of histone acetylation (AcH3K9lo and AcH3K9hi). Both primary and VPA-treated CD34+ cells were characterized by a significant proportion of CD34+AcH3K9hi cells, 52.2% ± 4.3% and 56.1% ± 2.4%, respectively, while this population was virtually absent in cultures exposed to CA (1.3% ± 0.5%, P = .001) indicating that ex vivo exposure of CD34+ cells to CA leads to a dramatic reduction in the degree of histone acetylation (Figure 3A).

Histone acetylation status of ex vivo–generated CD34+ cells and promoters of erythroid-specific genes. (A) Analyses of histone acetylation. Representative flow cytometric analysis of the histone H3K9 acetylation status of primary CD34+cells, VPA-treated CD34+ cells, and CD34+ cells cultured in the presence of cytokines alone after 7 days of culture. Cells were stained with H3K9 antibody to assess the acetylation level of lysine 9 residue of histone H3 (n = 3). One of 3 representative experiments is shown. (B) Analyses of acetylated histone H3K9/14 and H3K27 on the promoters of erythroid lineage-specific genes, a stem cell gene (c-Kit), and a nonhematopoietic gene (MyoD) of cytokines alone and VPA-treated CD34+ cells as determined by ChIP assay. A reduction of H3K9/14 and H3K27 acetylation was observed with all of the promoters on the CD34+ cells isolated from cell culture with cytokines alone compared with cells cultured cytokines + VPA. ChIP efficiency, in terms of the percentage of input DNA recovered by immunoprecipitation, was determined by Q-PCR (primers were designed within −1-kb promoters of the erythroid lineage-related genes). A sample with no antibody (No Ab) was used as a background control. The histogram represents mean percentage of fold change relative to input chromatin and SE (n = 3). (C) Percent acetylation of H3K9/14 and H3K27 relative to histone H3 in CD34+ cells from cultures containing cytokines alone and cytokines + VPA. The percentage of acetylation of H3K9/14 and H3K27 relative to total histone H3 was determined on the erythroid lineage-specific promoters, a stem cell gene (c-Kit), and a non hematopoietic gene (MyoD) of CD34+ cells isolated from cultures performed in the presence of cytokines alone and cytokines + VPA cultures after 7 days of incubation. Histogram represents mean ± SE of ChIP Q- PCR (n = 3).

Histone acetylation status of ex vivo–generated CD34+ cells and promoters of erythroid-specific genes. (A) Analyses of histone acetylation. Representative flow cytometric analysis of the histone H3K9 acetylation status of primary CD34+cells, VPA-treated CD34+ cells, and CD34+ cells cultured in the presence of cytokines alone after 7 days of culture. Cells were stained with H3K9 antibody to assess the acetylation level of lysine 9 residue of histone H3 (n = 3). One of 3 representative experiments is shown. (B) Analyses of acetylated histone H3K9/14 and H3K27 on the promoters of erythroid lineage-specific genes, a stem cell gene (c-Kit), and a nonhematopoietic gene (MyoD) of cytokines alone and VPA-treated CD34+ cells as determined by ChIP assay. A reduction of H3K9/14 and H3K27 acetylation was observed with all of the promoters on the CD34+ cells isolated from cell culture with cytokines alone compared with cells cultured cytokines + VPA. ChIP efficiency, in terms of the percentage of input DNA recovered by immunoprecipitation, was determined by Q-PCR (primers were designed within −1-kb promoters of the erythroid lineage-related genes). A sample with no antibody (No Ab) was used as a background control. The histogram represents mean percentage of fold change relative to input chromatin and SE (n = 3). (C) Percent acetylation of H3K9/14 and H3K27 relative to histone H3 in CD34+ cells from cultures containing cytokines alone and cytokines + VPA. The percentage of acetylation of H3K9/14 and H3K27 relative to total histone H3 was determined on the erythroid lineage-specific promoters, a stem cell gene (c-Kit), and a non hematopoietic gene (MyoD) of CD34+ cells isolated from cultures performed in the presence of cytokines alone and cytokines + VPA cultures after 7 days of incubation. Histogram represents mean ± SE of ChIP Q- PCR (n = 3).

A greater degree of total histone H3 was immunoprecipitated for the promoters of several erythroid lineage-specific genes, including Eklf, EpoR, Gata2, Pu.1, and a stem cell gene (c-Kit) from CD34+ cells from cultures containing CA compared with CD34+ cells from cultures containing CA plus VPA. By contrast the total histone H3 immunoprecipitated for the promoters of Gata1 and a nonhematopoietic stem cell gene (MyoD) were similar under the 2 culture conditions (supplemental Figure 2).

To determine whether VPA induced alterations in the expression levels of erythroid lineage-specific genes were governed by histone H3 acetylation, we performed ChIP assays of the upstream promoter regions (−1.0 kb) of the above-mentioned genes. The VPA-treated CD34+ cells were characterized by up-regulation of histone H3K9/14 and H3K27 acetylation compared with CD34+ exposed to CA. We monitored histone H3K9/14 and H3K27 modifications of the promoters of these genes in CD34+ cells reisolated after incubation under the described culture conditions. The degree of acetylated H3K9/14 and H3K27 in VPA-treated CD34+ cells for the promoters of each of these genes except MyoD was increased several fold, compared with CD34+ cells from cultures containing CA (Figure 3B). The higher levels of acetylated H3K9/14 and H3K27 in VPA-treated CD34+ cells cannot be attributed to a greater density of nucleosomes because the levels of total histone H3 precipitated was most frequently greater in the CD34+ cells from cultures containing CA (supplemental Figure 3). Furthermore, the greatest degree of H3K9/14 acetylation was observed within the promoters for Gata2 (7.4-fold), Gata1 (4.7-fold), Eklf (8.4-fold), and Pu.1 (3.8) while a relatively lower degree of acetylation was observed within the promoters for the EpoR (3.0-fold), c-Kit (1.2-fold), and MyoD (1.5-fold) in VPA-treated CD34+ cells. By contrast, H3K27 acetylation was greatest within the promoter for Eklf (9.7-fold), EpoR (4.7-fold), Gata1 (4.8-fold), and Gata2 (7.2-fold) compared with Pu.1 (2.9-fold) c-kit (2.4) and MyoD (1.0-fold) in VPA-exposed CD34+ cells.

The acetylation of H3K9/14 in these promoter regions in CA-treated CD34+ cells was elevated to a far smaller degree Eklf (1.08-fold), Gata1 (1.6-fold), c-Kit (0.85-fold) and MyoD (1.7-fold) while increased acetylation of H3K27 was observed within the promoters for Gata1 (2.9-fold), Pu.1 (2.1-fold), and c-Kit (2.4-fold). By contrast, the acetylation of the promoters for Eklf (1.0-fold) and EpoR (0.7-fold) differed by a smaller degree at H3K9/14 and H3K27 in CA and cytokines plus VPA-treated CD34+ cells (Figure 3B).

These results suggest that the acetylation of histones is a highly dynamic and reversible process and that lysine 9/14 and lysine 27 sometimes differentially modulate active marks on the chromatin structure leading to altered gene expression. Regulatory regions in VPA-treated CD34+ cells were significantly enriched for active chromatin marks compared with CD34+ cells exposed to CA. Acetylation of H3K9/14 and H3K27 relative to total histone H3 for the promoters of various erythroid-specific genes was greater in VPA-expanded cultures compared with cultures containing CA (20%-85%; Figure 3C).

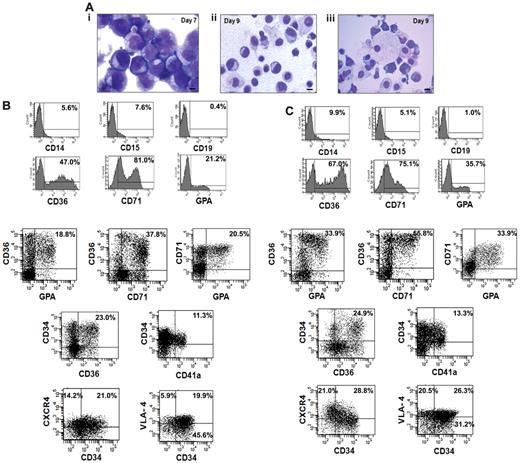

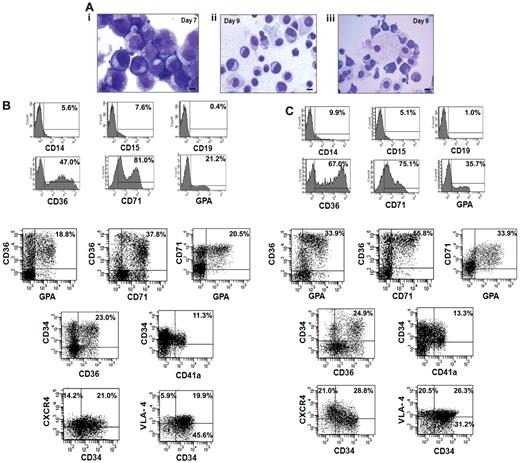

Morphologic and phenotypic analyses of ex vivo–generated EPC TPs

We next analyzed the cellular composition of the expanded cells that were generated from the CD34+ cells isolated from 5 small CB collections pooled to generate greater numbers of EPCs for infusion into NOD/SCID mice. The cultures were initiated with 8.0 × 106 of CB-CD34+ cells. After 7 days of cultures in the presence of cytokines plus VPA, 5.0 × 108 of cells were generated and after 2 additional days of incubation in the presence of Epo, SCF, and IL-3, 9.6 × 108 of total cells were present. The cells on day 7 appeared as immature mononuclear cells with an agranular cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli (Figure 4Ai), while by day 9 the cells were smaller with more compact nuclei and so-called erythroblastic islands (nucleated red cells surrounding macrophages) were observed (Figure 4Aii-iii). The VPA-treated cells after 7 days contained the following phenotypes: CD71+ (69.8% ± 12.9%), CD36+ (38.5% ± 8.6%), GPA+ (12.8% ± 6.4%), CD34+ (60% ± 6.7%), and CD34+CD90+ (46% ± 6.1%) cells while on day 9 the number of CD34+ cells as well as CD34+CD90+ cells had declined (30.0% ± 5%, 35.0 ± 6.7) and the percentage of CD71+ (71.7% ± 11.3%), CD36+ (67.7% ± 10.2%), and GPA+ (37.4% ± 7.3%) cells had increased. Figure 4, B and C, provides the phenotype of cells present in day-9 cultures compared with day-7 cultures. Day-9 cultures contained a greater proportion of EPCs and erythroid precursor cells capable of further proliferation CD34+CD36+ (21.4% ± 4.2% vs 27.4% ± 3.5%), CD36+GPA+ (19.8% ± 2.1% vs 33.9% ± 3.2%), CD36+CD71+ (36.8% ± 1.3% vs 55.5% ± 5.3%), and CD71+GPA+ (19.2% ± 1.7% vs 31.3% ± 3.6%). There was no significant increase observed in the number of megakaryocytic progenitors (CD34+CD41a+) after the 2 additional days of treatment with SCF, Epo, and IL-3 (11.3% ± 2.5% vs 13.3% ± 1.4%). The day-9 TP contained very limited numbers of CD19+ (1.4% ± 2.5%), CD14+ (11.1% ± 3.1%), or CD15+ (6.8% ± 2.5%) cells which were not significantly increased compared with the day-7 cell product. We also examined the expression of adhesion molecule CD49 days (VLA-4) and chemokine receptor CXCR4 in ex vivo–generated cells. As can be seen in seen Figure 4C greater numbers of both the CD34+ and CD34− cells expressed the chemokine CXCR4 (49.8%) and VLA-4 (46.8%) receptors, following the 2 additional days of cultures with SCF, IL-3, and Epo. Both CXCR4 and VLA-4 play pivotal roles in the trafficking and homing of hematopoietic cells to the BM.28

Characterization of the transfusion product. (A) Morphologic appearance of cells within the transfusion product. (i) Day-7 cells possessed an agranular cytoplasm. The nuclei of the cells had an open chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli. (ii) Day-9 cells were smaller with compact and relatively smaller nuclei. (iii) Erythroid islands characterized by normoblasts surrounding a macrophage were observed in day-9 cultures. Giemsa-Wright staining (×1000 magnification). (B-C) Phenotypic analyses of the transfusion product: FACS analyses of the cells after days 7 and 9 of incubation was performed by immunostaining with various mAbs to lineage-specific markers including CD36, CD71, GPA, CD14, CD15, CD19, and chemokine receptor marker CXCR4. One of 4 representative experiments is shown.

Characterization of the transfusion product. (A) Morphologic appearance of cells within the transfusion product. (i) Day-7 cells possessed an agranular cytoplasm. The nuclei of the cells had an open chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli. (ii) Day-9 cells were smaller with compact and relatively smaller nuclei. (iii) Erythroid islands characterized by normoblasts surrounding a macrophage were observed in day-9 cultures. Giemsa-Wright staining (×1000 magnification). (B-C) Phenotypic analyses of the transfusion product: FACS analyses of the cells after days 7 and 9 of incubation was performed by immunostaining with various mAbs to lineage-specific markers including CD36, CD71, GPA, CD14, CD15, CD19, and chemokine receptor marker CXCR4. One of 4 representative experiments is shown.

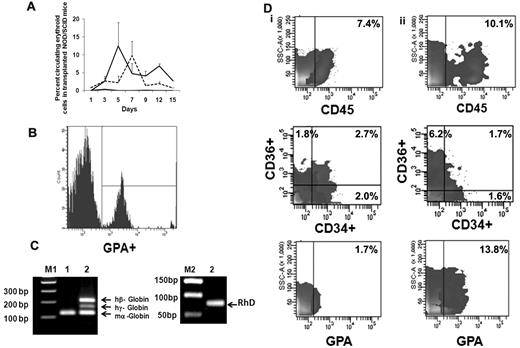

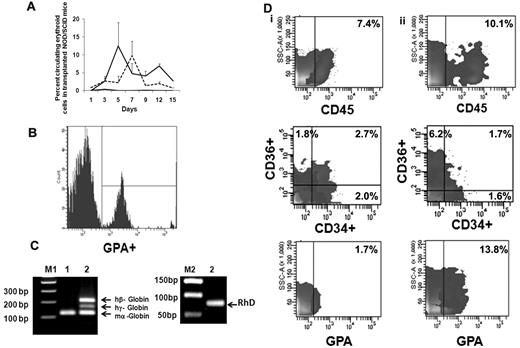

Functional characterization of EPC-TP in NOD/SCID mice

We next evaluated the behavior of ex vivo–expanded cells following their transfusion into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice. FACS analyses of mouse blood were performed on serial days (Figure 5A) by double-staining with LDS and hu-GPA. Beginning on day 1, nucleated human red cells LDS+GPA+ (0.85% ± 2.35%) were observed but there was no evidence of enucleated human red cells (LDS−GPA+). From day 3 until day 15 when the animals were killed, both human nucleated red cells and enucleated red cells were observed in the PB of NOD/SCID mice receiving the EPC cell product. The greatest number of enucleated human red cells (12.4% ± 6.8%) was observed 5 days after infusion of the expanded product (Figure 5B). On day 12 when 6.8% ± 0.5% of the cells in the PB were enucleated human red cells, the level of human CD14+ cells was only 0.4%-0.8% and CD19+ cells was 0.6%-1.0%. To further examine the duration of time that human red cells could be detected in the blood of recipient mouse blood after the delivery of the EPC-TP, another group of experiments were performed using NOD/SCIDγcnull mice which lack natural killer cells. Using this xenogeneic host, host donor cells were observed in the PB for 20 days (supplemental Figure 3). No nucleated and/or enucleated human cells were detected in the PB of mice, which received human type O+ blood cells alone. To confirm the presence of human RBCs in mice receiving the TP, we evaluated the expression of both human γ-globin and β-globin as well as RhD Ag in the blood of these mice. The RT-PCR analyses performed on day 15 revealed expression of both the hu β-globin gene, hu γ-globin, and RhD (Figure 5C). These data strongly support the presence of circulating human erythroid precursors and their progressive differentiation into mature RBC in vivo. In the initial experiment, human cell engraftment in the marrow and spleen engraftment was documented in mice that were killed on day15. In the marrow, 7.4% of the cells expressed hu-CD45+ while no evidence of human cell engraftment in the spleen was observed. The human cells present in the marrow were CD34+CD36− (2.0%), CD34−CD36+ (1.8%), CD34+CD36+ (2.7%), CD36 (4.5%), and GPA+ (1.7%; Figure 5Di); however, no evidence of CD33+, CD14+, CD19+, and CD41+ cells was noted. In mice receiving type O+ blood infusions alone, there was no evidence of human cell engraftment (0.1%-0.2%) determined on day 15. Using the NOD/SCIDγcnull mice as a xenogeneic recipient of the EPC-TP, hu-CD45+ cells (10.1%) were observed on day 30 in the marrow and spleen (2.5%). GPA+ cells were present in both the marrow (13.2%) and spleen (14.9%) on day 30. Furthermore, CD36+CD34− cells (6.2%) as well as CD34+CD36+ (1.7%) and CD34+CD36− (1.6%) were detected on day 30 (Figure 5Dii). In addition, there was evidence of CD33+ cells in bone marrow (2.3%) and CD19+ (1.1%) in the marrow but not the spleen of these mice. There was, however, no evidence of human CD41a+ and CD14+ cells observed in either the marrow or spleen of these mice. The presence of cells belonging to multiple hematopoietic lineages at day 30 in these mice suggests that the VPA-generated EPC-TP contained some marrow repopulating cells, findings which are in agreement with those of Araki and coworkers.31

Functional behavior of ex vivo–generated TPs in NOD/SCID mice. (A) Analyses of human erythroid cells in peripheral blood of NOD/SCID mice receiving the TP. The mean ± SD of the percentage of human erythroid cells in the blood of NOD/SCID mice on serial days as described by double staining with LDS (nuclei) and human GPA. LDS+GPA+ represents human EPCs (dotted line) and LDS−GPA+ represents erythrocytes (solid line). Evidence of human EPCs and/or erythrocytes was not observed in control mice (black line indicates LDS−GPA+; and LDS+GPA+, gray line). Two to 3 mice were analyzed in each group (n = 2). (B) Representative histogram of human erythroid cells present on day 5 in the peripheral blood of NOD/SCID mouse. Similar results were obtained in an additional experiment. (C) Detection of human globins (β and γ) in the NOD/SCID mouse blood 15 days following the infusion of the transfusion product. Primers of mouse α-globin, human β and γ globins were mixed together and expression of globin mRNA was analyzed from cDNA prepared from mouse blood on day 15 by RT-PCR. Hu-β (212 bp), hu-γ (165 bp), RhD antigen (90 bp), and mouse-α (122 bp) gene products are shown on a 1.8% agarose gel. Lanes M1 and M2 contain DNA marker (a 100-bp ladder and 50-bp ladder); lane 1, blood from control NOD/SCID mouse; and lane 2, blood from NOD/SCID mouse infused with the transfusion product. One representative of 2 experiments is shown. (D) Human cell engraftment in the marrow of NOD/SCID mice. (i) Mouse bone marrow was harvested and analyzed on day 15 (NOD/SCID mice, n = 2) and (ii) in separate series of experiment NOD/SCIDγcnull mice day 30 (n = 3) after the infusion of the TP.

Functional behavior of ex vivo–generated TPs in NOD/SCID mice. (A) Analyses of human erythroid cells in peripheral blood of NOD/SCID mice receiving the TP. The mean ± SD of the percentage of human erythroid cells in the blood of NOD/SCID mice on serial days as described by double staining with LDS (nuclei) and human GPA. LDS+GPA+ represents human EPCs (dotted line) and LDS−GPA+ represents erythrocytes (solid line). Evidence of human EPCs and/or erythrocytes was not observed in control mice (black line indicates LDS−GPA+; and LDS+GPA+, gray line). Two to 3 mice were analyzed in each group (n = 2). (B) Representative histogram of human erythroid cells present on day 5 in the peripheral blood of NOD/SCID mouse. Similar results were obtained in an additional experiment. (C) Detection of human globins (β and γ) in the NOD/SCID mouse blood 15 days following the infusion of the transfusion product. Primers of mouse α-globin, human β and γ globins were mixed together and expression of globin mRNA was analyzed from cDNA prepared from mouse blood on day 15 by RT-PCR. Hu-β (212 bp), hu-γ (165 bp), RhD antigen (90 bp), and mouse-α (122 bp) gene products are shown on a 1.8% agarose gel. Lanes M1 and M2 contain DNA marker (a 100-bp ladder and 50-bp ladder); lane 1, blood from control NOD/SCID mouse; and lane 2, blood from NOD/SCID mouse infused with the transfusion product. One representative of 2 experiments is shown. (D) Human cell engraftment in the marrow of NOD/SCID mice. (i) Mouse bone marrow was harvested and analyzed on day 15 (NOD/SCID mice, n = 2) and (ii) in separate series of experiment NOD/SCIDγcnull mice day 30 (n = 3) after the infusion of the TP.

Discussion

Gene expression in mammalian cells is strongly influenced by chromatin organization.32,33 Chromatin organization is influenced by chromatin remodeling and histone-modifying complexes. Because CMA differentially affect gene expression, we attempted to identify CMA which would favor commitment to EPCs. The intent was to generate sufficient numbers of EPCs to serve as a TP. This product would differ from presently used TP in that it would be composed of EPCs and erythroid precursor cells which retain an extensive proliferative potential and would possibly following infusion transiently engraft and continue to generate red cells for a defined period providing a sustained source of transfused cells. The process reported here includes 2 steps: an initial 7-day incubation of CB-CD34+ cells in the presence of an HDACI that leads to the expansion of EPCs followed by a second step where cells are exposed to a cytokine milieu that favors terminal erythroid maturation (SCF, IL-3, and Epo). We evaluated the utility of several HDACIs to promote erythroid commitment and demonstrated that VPA was the optimal agent of the 3 examined. Because we did not evaluate the potential of numerous other HDACI currently available, we cannot be certain that VPA is the optimal agent for such purposes.22-24 The most compelling evidence provided which indicates that VPA treatment can influence lineage fate decisions was provided by the clonogenic analyses of single CD34+ cells demonstrating that virtually all of the CD34+ cells in VPA-treated culture were EPCs.

We hypothesized that the processes associated with differentiation are mediated by DNA methylation and histone modifications allowing the stable silencing of a large fraction of the genome.22 Overexpression of Bmi1, Dnmt1, and Ezh2 in CD34+ cells has been shown to be associated with long-term maintenance of an HSC/HPC phenotype.34 Erythroid lineage commitment and differentiation is known to progress in response to a transcriptional program particularly regulated by lineage-restricted transcription factors.35,36 The ratio of Gata1 and Gata2 expression defines commitment of an HSC toward EPCs. Gata2 is predominantly expressed in HSCs/HPCs12 whereas Gata1 regulates the expression of many erythroid genes and terminal differentiation of erythroid cells.37 Lineage-restricted transcription factors work in dual ways, first by inducing a new gene expression program but at the same time halting or inactivating key transcription factors that lead to commitment to other lineages. Pu.1, for instance, which inhibits erythroid differentiation by blocking Gata1 DNA binding but promotes monocytic/granulocytic differentiation, was down-regulated to a greater extent in VPA-treated CD34+ cells. Furthermore, the up-regulation of Smad5 in the VPA-treated CD34+ cells was consistent with the presence of a primitive EPC population because the BMP/Smad pathway directs the transcription factors Eklf and Gata1 during the earliest stages of erythroid development.38

The phenotypic analyses of the VPA-treated cell product revealed the presence of cells at various stages of human erythropoiesis accompanied by a reduction in number of cells associate with myelopoiesis and B-cell lymphopoiesis. CD36 is expressed by macrophages, monocytes, and platelets; it has been also shown to be expressed by more differentiated EPCs (CFU-E).39 Both CD34 and CD71 have been shown to be expressed by BFU-E and the expression of CD71 has been reported to precede that of CD36.12 The VPA-treated cultures were characterized by a large number of cells that coexpressed CD34 and CD36 but were GPA negative, this likely represents a cell population residing between a BFU-E and CFU-E. The 2 additional days of incubation with SCF, IL3, and Epo successfully promoted further differentiation of erythroid precursor cells (CD36+CD71+ cells). The chemokine receptor (CXCR4) interacts with CXCL12 to promote trafficking of HSCs/HPCs to the BM.40 Specially, CXCR4 has been shown to be expressed by human BFU-E and is thought to play an important role in the homing and/or retention of EPCs and erythroid precursors within the marrow.41 VPA treatment increased both CXCR4 and VLA-4 expression of HPCs.26 VLA-4 also determines HSC/HPC trafficking and also been shown to contribute to the creation of erythroblasts islands.41-43 Because HDACI can affect multiple biologic events, the exact mechanism by which VPA promotes commitment to the erythroid lineage remains the subject of continued investigations.

The histone modifications likely antagonize the gene silencing associated with ex vivo culture in the presence of CA and prepare HPC chromatin for transcriptional activation.27 ChIP assays demonstrated a several fold increase in levels of AcH3K9/14 and AcH3K27 after treatment with VPA. The degree of acetylation of different lysine residues on histone H3 was variable on promoters of the same gene reflecting the contextual dynamics of the acetylation process. In addition, VPA can lead to stable changes in the epigenome by affecting the state of DNA methylation of both genomic DNA and genes promoters.44 Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that acetylation of nonhistone proteins might also contribute to the biologic activities observed.45

In this report, we used a surrogate immune-deficient mouse assay developed by others2,4,24 to test the functional behavior of the VPA-expanded EPC-TP and monitored both circulating hu-nucleated as well as enucleated erythroid cells in vivo. We observed hu β-globin and fetal γ-globin transcripts in the circulating blood of mice, predominantly hu β-globin and RhD antigen on day 15 confirming the presence of human hemoglobin in the PB of these animals and indicate this switch from fetal γ-globin to adult β-globin. The prolonged presence of human nucleated as well as enucleated red cells in the NOD/SCID mice receiving the VPA-treated TP is likely because of the engraftment of the EPCs in the marrow of recipient mice. This degree of engraftment may be a consequence of the low dose of irradiation administered to the mice before infusion, or the higher expression of CXCR4 and VLA4 associated with VPA treatment of the TP. We hypothesize that such marrow cell populations continue to produce human red cells in vivo in response to the human Epo which was administered to the mice. The VPA-treated cells also were able to engraft the marrow of NOD/SCID mice on day 30 suggesting that they contained functional marrow repopulating cells. Unlike sequential treatment with 5azaD followed by TSA of CB-CD34+ cells, VPA treatment has recently been reported to lead to stem cell maintenance rather than expansion indicating that different CMA might affect CD34+ cell behavior in distinct fashions. It is important to emphasize the NOD/SCID assay system remains a surrogate assay system with which to assess the biologic potential of the EPC TP as well as marrow repopulating cells. One can only speculate about the fate of such a EPC product when infused into immune competent hosts not receiving conditioning with radiation as would occur if they were infused into an anemic patient requiring transfusion therapy. Another important barrier to the implementation of this strategy in man is the need to determine the dose of cells which would be anticipated to result in improvement of the degree of anemia of a particular patient. Because of differences between a xenogeneic model and a potential anemic patient receiving an ex vivo–generated allogeneic human cell product, it would be impossible to accurately predict the number of such cells that would be clinically effective from the data generated from the in vivo studies reported here. In fact, human red cells were not observed in the PB of those animals that received type O+ red cells in large numbers alone. Preclinical studies using more appropriate large immune competent animal models, therefore, would be required to estimate the size of an ex vivo–generated TPs that would be clinically useful in humans.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs Camelia Iancu-Rubin, Shiraz Mujtaba, and Girdhari Lal for providing histone H3, acetelyated H3K9, H3K9/14, and H3K27 antibodies. We also acknowledge Wei Zhang, Daniel Yoo, Adam Austin, Jiapeng Wang, and Michael Feldman for their technical assistance. We thank Dr Annarita Migliaccio for providing the microscope facility. We appreciate Dr James J. Bieker for providing the mouse and human globin primers and for critical review of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: P.C. designed, performed, analyzed, and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; D.B. assisted with in vivo experiments; and R.H. designed, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ronald Hoffman and Pratima Chaurasia, Division of Hematology/Oncology, Tisch Cancer Institute, Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Pl, Box 1079, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: ronald.hoffman@mssm.edu, pratima.chaurasia@mssm.edu.

, cytokines alone;

, cytokines alone;  , cytokines + VPA (n = 4).

, cytokines + VPA (n = 4).