Abstract

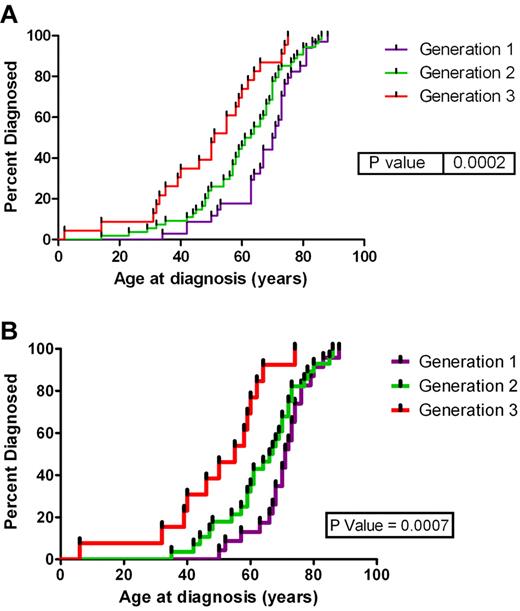

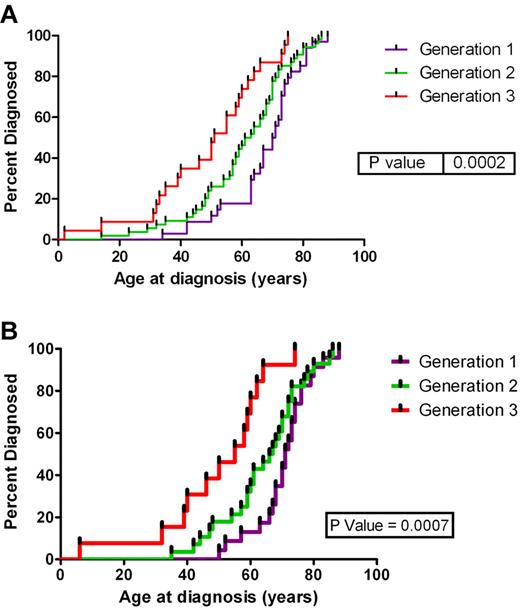

We describe a collection of 11 families with ≥ 2 generations of family members whose condition has been diagnosed as a hematologic malignancy. In 9 of these families there was a significant decrease in age at diagnosis in each subsequent generation (anticipation). The mean age at diagnosis in the first generation was 67.8 years, 57.1 years in the second, and 41.8 years in the third (P < .0002). This was confirmed in both direct parent-offspring pairs with a mean reduction of 19 years in the age at diagnosis (P = .0087) and when the analysis was repeated only including cases of mature B-cell neoplasm (P = .0007). We believe that these families provide further insight into the nature of the underlying genetic mechanism of predisposition in these families.

Introduction

Studies have established that a family history of hematologic malignancy (HM) is a risk factor for the development of a HM.1-5 However, in the literature collections of large families with multiple cases of varied types of HMs are relatively rare,1 and most studies of familial HM focus on one major subtype in each family such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia, and Hodgkin lymphoma.4,6-8 In a number of families with HM, the phenomenon of “anticipation” has been described.4 Anticipation is defined as the onset of the disease in question at an earlier age or disease severity in successive generations, and it has implications for the nature of the genetic condition that underpins it.

We are studying 13 families, ascertained from a population-based study conducted between 1972 and 1980 in Tasmania.9 Herein, we describe 11 of these families that have ≥ 2 generations affected with a HM. These families have been updated, and the current and past generations were included and cross-referenced with names from the Tasmanian Cancer Registry and the genealogic databases of the Menzies Research Institute. These families have been recently published,10 but they are continuously being updated with new cases of HMs. We reviewed our families to determine whether anticipation could be shown. Here, we describe 9 families with HM that exhibit anticipation. In contrast to most prior reports, we show that the phenomenon also occurs in families in which the predominant HM is other than CLL. The demonstration of anticipation is shown both by whole generational analysis and by assessment of parent-offspring pairs.

Methods

Families from the original study

The families from the original study were reviewed and prioritized for further study, based on the number of cases affected, multiple generations affected, or sibling pairs affected. This study has received ethical approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee, Tasmania Network.

Confirmation of diagnosis

Medical and pathology records from the Royal Hobart Hospital, flow cytometric records from the University of Tasmania's Oncology and Immunology Laboratory, files from the 1970s study,9 and records of the Tasmanian Cancer Registry were obtained. Pathology samples were located and reviewed by a hematologist (E.M.T.) to confirm the type of HM.

Statistical analysis

Student t tests were generated with Microsoft Excel. Pedigrees were drawn with SmartDraw software. Anticipation was assessed with a log-rank test for trend with the use of GraphPad Prism software Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc).

Results and discussion

In these 11 families there were 123 people affected with a HM, and an overall mean of 3 generations (2-5 generations) were affected. The male-to-female ratio was 91:32. Reconfirmation of diagnosis was sought in all cases. A total of 98 cases could be reconfirmed and classified according to the current World Health Organization classification of HMs.11 The 25 that could not be reconfirmed consisted of 4 cases not diagnosed in Tasmania and 21 cases that were in the original study,9 but whose pathology records are now no longer available. However, for these 25 cases the age at diagnosis and the type of HM was recorded in the original study; thus, these cases are referred to as confirmed cases.

The mean age at diagnosis was 56.5 years (2-88 years). Figure 1A shows the age at diagnosis for the first 3 generations for the 11 families. We have restricted our analysis of anticipation to the first 3 generations because of limited follow-up time in the fourth and fifth generations. However, evidence supports anticipation in these generations (test for trend across all 5 generations, P < .0001), noting that the fifth generation consists of only 3 cases in one family. The mean age at diagnosis for the first generation in these families was 67.8 years compared with 57.1 years for the second generation (P = .0437) compared with 41.8 years for the third generation (P = .0094). There were 5 direct affected parent-offspring pairings, the pedigrees of these families are shown in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The mean age of the parents was 63.8 years compared with 44.8 years in the offspring (P = .0087). This is a mean reduction in the age at diagnosis by 19 years. The types of HM found in each generation of these families are listed in Table 1. The analysis of the age at diagnosis was repeated for all cases of mature B-cell neoplasms (including CLL) (Figure 1B) (therefore addressing the argument of young onset diseases only occurring in the younger generations), and there was still a significant decrease in the age at diagnosis for each subsequent generation (P = .0007).

Age at diagnosis by generation. Age at diagnosis by generation for (A) all subjects in the first 3 generation and (B) subjects with a mature B-cell neoplasm.

Age at diagnosis by generation. Age at diagnosis by generation for (A) all subjects in the first 3 generation and (B) subjects with a mature B-cell neoplasm.

The phenomenon of “anticipation” has been described in relation to several familial diseases, including HM.4 In the literature anticipation has been reported in families with CLL with a reduction in the age at diagnosis by 15 years.12 It has also been observed in families with acute myeloid leukemia that the mean age at diagnosis in the first generation was 57 years, second generation was 32 years, and 13 years for the third generation.6 Anticipation has also been observed in families with lymphoma,4 families with plasma cell dyscrasia13 and families with Hodgkin lymphoma.14 In fact > 140 families with HMs have been documented in the literature that show anticipation,4 although this phenomenon is not universally observed.15 It is often argued that this phenomenon is because of selection bias; however, if this was the case, then it would be present in all families. It is also argued that the youngest generation is not old enough to have developed a HM in their sixth decade, but in the 11 families no one in the first generation developed a HM before the age of 35 years. When this analysis was repeated with just one type of HM, mature B-cell neoplasm (n = 60), anticipation was still present. Note that the 2 families that did not show a consistent decrease in the age at diagnosis for each generation were families that were studied because of a cluster of affected siblings whose parents were first cousins. It is well recognized that children of consanguineous relationships are at an increased risk of recessive disorders.16

In the other 9 families there was a reduction in the age at diagnosis for each subsequent generation. This was confirmed in direct parent-offspring affected cases with a mean reduction of 19 years in the age at diagnosis between the generations. Previous reports have shown that anticipation in familial HM has been seen across 3 generations4 ; we now show affected persons with anticipation across 5 generations in 1 family and across 4 generations in an additional 2 families. This is consistent with a dominantly acting mutation in 9 families and a recessively acting mutation in 2 families.

Anticipation is reported to be consistent with a dominantly acting mutation; however, the causative mutation in HMs has not been identified. In other disorders in which anticipation has been reported, it has been found to be because of an unstable dynamic mutation that expands with each generation. This type of mutation has been implicated in > 40 diseases.17 Triplet repeats have been studied in familial CLL; however, no causative repeat was identified.18

It is clearly recognized in the literature that there is a genetic basis for the familial risk of HMs; however, genome-wide association studies of CLL,19 childhood ALL,20,21 and non-Hodgkin lymphoma 22 have identified genetic variants that account for only a small percentage of the heritable risk. We believe that further study of these families will provide valuable insights into the genetic predisposition underlying familial HMs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the David Collins Leukemia Foundation of Tasmania, the Royal Hobart Hospital Research Foundation, the Cancer Council Tasmania and the Australian Cancer Research Foundation.

We dedicate this publication to the memory of Jean Panton.

Authorship

Contribution: E.M.T. wrote the manuscript, confirmed the pathology, and reviewed all medical records; R.J.T. and J.M.S. provided statistical support; A.B. updated the pedigrees; K.A.M. provided hematology input and assisted with the manuscript preparation; R.M.L. provided clinical input and assisted with the manuscript preparation; and S.J.F. and J.L.D. assisted with the manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Elizabeth M. Tegg, Menzies Research Institute, Medical Science 1 Bldg, 17 Liverpool St, Hobart, TAS, 7000 Australia; e-mail: emtegg@utas.edu.au.