Abstract

Bisphosphonates are mainly used for the inhibition of osteoclast-mediated bone resorption but also have been shown to induce γδ T-cell activation. Using IL-2–primed cultures of CD56+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells, we show here that zoledronic acid (zoledronate) could induce IFN-γ production not only in γδ T lymphocytes but, surprisingly, also in natural killer (NK) cells in a manner that depended on antigen-presenting cells, which share properties of inflammatory monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs; here referred to as DC-like cells). In the presence of γδ T lymphocytes, DC-like cells were rapidly eliminated, and NK cell IFN-γ production was silenced. Conversely, in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes, DC-like cells were spared, allowing NK cell IFN-γ production to proceed. γδ T cell–independent NK cell activation in response to zoledronate was because of downstream depletion of endogenous prenyl pyrophosphates and subsequent caspase-1 activation in DC-like cells, which then provide mature IL-18 and IL-1β for the activation of IL-2–primed NK cells. Pharmacologic inhibition of caspase-1 almost abolished IFN-γ production in NK cells and γδ T lymphocytes, indicating that caspase-1–mediated cytokine maturation is the crucial mechanism underlying innate lymphocyte activation in response to zoledronate.

Introduction

The bisphosphonates zoledronate and pamidronate are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic bone disease of hematopoietic tumors such as multiple myeloma1,2 and nonhematopoietic tumors such as breast3 and prostate cancer.4 Inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase, an enzyme of the mevalonate pathway for cholesterol biosynthesis and protein prenylation,5 is one important mechanism for bisphosphonate effects on bone resorption.1,4 Inhibition of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase leads to farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) deprivation and the subsequent failure to perform farnesylation and geranylgeranylation of small guanosine triphosphatases (GTPases) of the RAS superfamily. Inhibition of RAS signaling because of the disruption of membrane anchoring of these GTPases eventually prevents osteoclast-mediated bone resorption.6,7

In addition to their effects on bone metabolism, bisphosphonates may have immunomodulatory effects, particularly on the innate immune system.8-11 Evidence for the stimulation of γδ T lymphocytes by bisphosphonates was obtained when expansion of γδ T lymphocytes was observed in patients who had acute-phase reactions after their first treatment with pamidronate.12 Inhibition of FPP synthase by bisphosphonates leads to the accumulation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate that can be specifically recognized by γδ T lymphocytes expressing the Vδ2Vγ9 T-cell receptors.13 Hematopoietic tumor cell lines such as Daudi (Burkitt lymphoma) or RPMI 8226 (myeloma) are specifically recognized and lysed by these γδ T lymphocytes in vitro.14,15 Moreover, γδ T lymphocytes have recently been shown to recognize and kill zoledronate-sensitized chronic myelogenous leukemia cells even after acquisition of imatinib resistance.16 Accumulation of mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells has been shown to be a powerful danger signal inducing γδ T-cell activation.17 The recognition of such nonpeptide antigens by γδ T lymphocytes suggests a surveillance function of these T lymphocytes for infected or transformed cells.9,18 The idea of tumor immune surveillance by γδ T lymphocytes resulted in clinical studies, which used bisphosphonate in combination with IL-2 to expand γδ T lymphocytes in patients with hematologic cancers such as myeloma19 and lymphoma20 as well as in solid tumors such as prostate21 and breast cancer.22 For a long time, other effector lymphocytes than γδ T lymphocytes have not been implicated in bisphosphonate-mediated immune modulation. Maniar and colleagues only recently demonstrated that zoledronate-activated γδ T lymphocytes can costimulate the cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells primed by immobilized human IgG1 in a manner that partially depends on the interaction of CD137 ligand expressed on activated γδ T lymphocytes with CD137 expressed on NK cells.23

Here, we show that zoledronate, the most potent bisphosphonate currently available, can activate human NK cells in a dendritic cell (DC)–dependent but γδ T cell–independent manner. Mechanistic studies revealed that zoledronate-induced deprivation of prenyl pyrophosphates translates into caspase-1–mediated maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 followed by the activation of IL-2–primed NK cells.

Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Zoledronate (Zometa) was from Novartis Pharma. Pamidronate (Pamidronat Dinatrium Mayne) was obtained from Mayne Pharma. FPP and GGPP were purchased from Echelon Biosciences. Stock solutions of FPP and GGPP were prepared in H2O. Stock solutions were prediluted in culture medium. The maximal amount of H2O was calculated to be 0.2 μL per 200 μL (96 well). In control experiments, this had no effect. Recombinant human IL-2 (proleukin) was from Novartis. Caspase-1 inhibitor Ac-Tyr-Val-Ala-Asp-2,6-dimethylbenzoyloxymethyl-ketone (YVAD) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals.

Monoclonal antibodies and sources are as follows: anti-CD56 (N901-PE) was from Beckman Coulter; anti-CCR2 (48 607-APC) was from R&D Systems; anti–HLA-ABC (G46-2.6-FITC), anti–HLA-DR (TÜ36-PE), anti-CD80 (L307.4-PE), anti-CD86 (FUN-1-FITC), anti-CD54 (HA58-PE), anti-CD16 (B73.1-PE), anti-CD7 (M-T701-Pe-Cy5), anti-CD3 (SK7-PerCP-Cy5.5), anti-CD14 (MφP9-FITC, MφP9-APC), anti-CD19 (HIB19-PE), and anti-CD56 (B159, NA/LE) were from BD Biosciences; anti–T-cell receptor (TCR) Vδ2 (IMMU 389-FITC) was from Beckman Coulter; anti-NKp46 (9E2-PE) was from Miltenyi Biotec; anti–IFN-γ (B27-FITC or B27-PE) was from BD Biosciences; neutralizing anti–IL-18 (125-2H) was from MBL; and neutralizing anti–IL-1β (8516) and anti–IL-12 (24 910) were from R&D Systems. IgG1 control antibody (103.7) was from BD Biosciences.

Magnetic cell separation

The study was approved by the Innsbruck Medical University Review Board. All donors (n = 10) gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for the use of their residual buffy coats for research purposes. CD56+ cells or CD14+ cells were purified from PBMCs using CD56 or CD14 microbeads and LS columns. In some experiments, CD56+ PBMCs were depleted of CD14+ cells using CD14 microbeads and LD columns. In other experiments, CD56+ PBMCs were depleted of CD3+ cells using CD3 microbeads and LD columns. All procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). To check for stimulatory effects of cell labeling with anti-CD56 antibody, PBMCs were treated with the no azide/low endotoxin (NA/LE) B159 anti-CD56 antibody (BD Biosciences). Under all conditions tested, anti-CD56 antibody had no effect.

Cell culture and stimulation

All cell cultures were performed in complete BioWhittaker RPMI 1640 (Lonza) supplemented with 10% FCS (HyClone Laboratories). For cytokine measurements, cells (1 × 106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 (100 U/mL) either alone or in combination with bisphosphonate (10 or 30μM) in 96-well round-bottomed plates (0.2 mL). After 1-3 days, supernatants were harvested for cytokine analysis. For neutralizing and blocking assays, cultures were preincubated with specific antibodies or inhibitors.

Cytokine measurements

Cytokine levels were assessed on days 1 to 3 in culture supernatants using cytometric cytokine bead arrays (CBAs; BD Biosciences). The T-helper (Th)1/Th2 CBA was used in combination with the inflammation CBA from BD Biosciences to detect IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and IL-12p70. Samples were analyzed with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer and FCAP Array 1.0.1 software from BD Biosciences.

For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, cells (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated in RPMI 1640–10% FCS with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or bisphosphonate (10 and 30μM) plus IL-2 for 20 hours (day 1) or 44 hours (day 2). During the last 3-4 hours cells were treated with brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) and were then harvested, washed, and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti-TCRVδ2 or anti-CD3 or anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed twice and treated with FIX&PERM (AN DER GRUB Bio Research). Fixed, permeabilized cells were stained with fluorochrome-conjugated anti–IFN-γ antibody. After 2 more washes, the cells were analyzed with a FACSCanto II flow cytometer and FACS Diva 6.1.2 as well as FlowJo Version 7.2.5 software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical analyses

Individual group comparisons were performed using independent Student t tests and Excel (Microsoft) as well as SPSS 13.0 software (SPSS). Differences for which P was < .05 are reported as significant.

Results

Zoledronate is more potent than pamidronate in inducing IFN-γ production in CD56+ PBMCs: role of CD56+ inflammatory DC-like cells

In extension of our previous studies of DC-mediated γδ T-cell activation,24 we compared the immunostimulatory capacities of zoledronate and pamidronate (Figure 1A), which both inhibit FPP synthase within the mevalonate pathway (Figure 1B). In previous studies, CD56+ PBMCs proved to be a suitable and reliable experimental system for the study of DC-mediated innate lymphocyte activation.24,25 CD56+ PBMCs, which can readily be prepared by magnetic cell separation, consist of T lymphocytes including γδ T lymphocytes (Vδ2+), NK cells (NKp46+), and accessory cells (CD14+; supplemental Figures 1-2, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), which share properties of monocytes and DCs (here referred to as DC-like cells). Freshly isolated CD56+ DC-like cells expressed various surface antigens related to antigen presentation, which were strongly and rapidly up-regulated during short-term culture (Figure 1C). The various subsets within CD56+ PBMCs also can be demonstrated in total PBMCs by gating on and selectively analyzing CD56+ cells (supplemental Figure 1). We and others have previously characterized these circulating DC-like cells24-27 and found that they are phenotypically similar to monocyte-derived DCs generated in vitro with GM-CSF and type 1 IFN.28,29 Such IFN-induced DCs, which express elevated levels of molecules related to antigen presentation and potently induce antigen-specific immune responses in vitro and in vivo,28,30,31 were recently shown to be CD56+CD14+.29

Chemical structures, metabolic pathways, and phenotype of CD56+ DC-like cells. (A) Chemical structures of zoledronate and pamidronate. Redrawn from Russel et al.50 (B) Simplified depiction of mevalonate metabolic pathways. (C) Phenotype of CD56+ DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs were isolated using CD56 microbeads, and CD14+ cells were immediately analyzed for the surface expression of various antigens related to antigen presentation by flow cytometry (d0). CD56+ PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) also were cultured in the absence of exogenous cytokines for 20 hours and were then again subjected to flow cytometric analyses (d1). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is shown for each individual staining (− MFI of isotype control).

Chemical structures, metabolic pathways, and phenotype of CD56+ DC-like cells. (A) Chemical structures of zoledronate and pamidronate. Redrawn from Russel et al.50 (B) Simplified depiction of mevalonate metabolic pathways. (C) Phenotype of CD56+ DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs were isolated using CD56 microbeads, and CD14+ cells were immediately analyzed for the surface expression of various antigens related to antigen presentation by flow cytometry (d0). CD56+ PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) also were cultured in the absence of exogenous cytokines for 20 hours and were then again subjected to flow cytometric analyses (d1). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is shown for each individual staining (− MFI of isotype control).

We have recently found that circulating CD56+ DC-like cells seem to be the preferred accessory cells for NK cell activation in response to stimulation with statins.25 To further characterize CD56+CD14+ DC-like cells and to assign them to known subclasses of monocytes or DCs, the cells were stained for CCR2 and CD16. As shown in Figure 2 (top panel), CD56+CD14+ DC-like cells expressed CCR2 but lacked CD16 consistent with the phenotype of inflammatory DC-like cells.32 CD56+ lymphocytes were also CCR2+ but contained a CD16high population, which can be considered to be bona fide NK cells (Figure 2 middle panel). CD56+ DC-like cells were CD7−, whereas CD56+ lymphocytes were CD7+ (Figure 2 middle panel). CD56+ DC-like cells did not express the B-cell marker CD19 (Figure 2). Conventional blood monocytes (CD14+CD56−) presented with a similar phenotype but also contained the well-known small CD16+ subset (Figure 2 bottom panel).32

CD56+ DC-like cells are CCR2+CD16− consistent with the phenotype of inflammatory DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs or CD14+CD56− PBMCs were isolated using either CD56 or CD14 microbeads. Cells were stained for the markers indicated and selective forward scatter/side scatter gating was used to analyze either monocytes/DC-like cells or lymphocytes. A representative donor is shown.

CD56+ DC-like cells are CCR2+CD16− consistent with the phenotype of inflammatory DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs or CD14+CD56− PBMCs were isolated using either CD56 or CD14 microbeads. Cells were stained for the markers indicated and selective forward scatter/side scatter gating was used to analyze either monocytes/DC-like cells or lymphocytes. A representative donor is shown.

The potency of bisphosphonates is assessed by their relative ability to inhibit osteoclast function. A ranking of anti-osteoclast activity indicates that zoledronate, which differs from pamidronate by having a heterocyclic side chain containing two nitrogens (Figure 1A), is much more potent than pamidronate.1 Consistently, zoledronate induced significantly higher amounts of IFN-γ (Figure 3A left panel; P < .01).

Zoledronate but not pamidronate effectively induces IFN-γ production in CD56+ PBMCs: abrogation of the IFN-γ response after depletion of CD14+ DC-like cells but residual IFN-γ production after depletion of CD3+ cells (T lymphocytes). (A) CD56+ PBMCs or CD56+ PBMCs depleted of CD14+ DC-like cells (1 × 106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2, bisphosphonate (zol, pam), or bisphosphonate plus IL-2. IFN-γ levels were determined on day 3. (B) CD56+ PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) or CD56+ PBMCs depleted of CD3+ cells (T lymphocytes including γδ T lymphocytes) were stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate (zol), or zoledronate plus IL-2 (dose and time dependence). Results are representative of 5 independent experiments.

Zoledronate but not pamidronate effectively induces IFN-γ production in CD56+ PBMCs: abrogation of the IFN-γ response after depletion of CD14+ DC-like cells but residual IFN-γ production after depletion of CD3+ cells (T lymphocytes). (A) CD56+ PBMCs or CD56+ PBMCs depleted of CD14+ DC-like cells (1 × 106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2, bisphosphonate (zol, pam), or bisphosphonate plus IL-2. IFN-γ levels were determined on day 3. (B) CD56+ PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) or CD56+ PBMCs depleted of CD3+ cells (T lymphocytes including γδ T lymphocytes) were stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate (zol), or zoledronate plus IL-2 (dose and time dependence). Results are representative of 5 independent experiments.

Magnetic depletion of CD14+ DC-like cells from CD56+ PBMCs before stimulation almost abolished IFN-γ production (Figure 3A right panel; P < .05), confirming that bisphosphonate-induced IFN-γ production requires accessory cells.13,24 In contrast, however, we surprisingly observed that IFN-γ production in response to zoledronate, which occurred in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 3B left panel), was not abrogated in CD56+ PBMCs that had been depleted of CD3+ cells, that is, all T lymphocytes including γδ T lymphocytes (Figure 3B right panel). The still substantial residual levels of IFN-γ, which are produced in the absence of CD3+ cells, indicated that other cellular sources of IFN-γ than γδ T lymphocytes must exist.

Zoledronate but not pamidronate induces IFN-γ production in NK cells: γδ T lymphocytes regulate survival of DC-like cells

To identify the cellular sources of IFN-γ within CD56+ PBMCs, we performed intracellular staining of IFN-γ after stimulation with IL-2 alone or in combination with either zoledronate or pamidronate. Cells were counterstained for TCRVδ2 to identify γδ T lymphocytes, for CD3 to distinguish T lymphocytes (CD3+) from NK cells (CD3−) or for CD14 to identify DC-like cells.

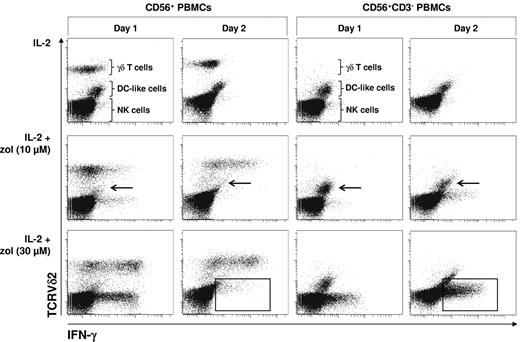

As a first step, we monitored DC-like cells. After stimulation with IL-2 alone, DC-like cells could be detected. In the presence of IL-2 plus zoledronate, however, DC-like cells were rapidly eliminated, indicative of either γδ T-cell cytotoxicity directed against DC-like cells or NK cell cytotoxicity costimulated by zoledronate-activated γδ T lymphocytes.23 In contrast, in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes, which were depleted before cell stimulation, DC-like cells survived even in the presence of zoledronate, indicating that γδ T lymphocytes control the survival of DC-like cells. Figure 4A also shows that, after T-cell depletion, there was residual IFN-γ production, which cannot be attributed to γδ T lymphocytes.

Zoledronate but not pamidronate induces IFN-γ production in NK cells: γδ T lymphocytes regulate survival of DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 20 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with bisphosphonate (10 or 30μM) plus IL-2. Cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface CD14 (DC-like cells; A) or TCRVδ2 (γδ T lymphocytes) and CD3 (all T lymphocytes; B). Frames point out DC-like cells. Arrows point out Vδ2− and CD3− cells (ie, NK cells) producing IFN-γ. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Zoledronate but not pamidronate induces IFN-γ production in NK cells: γδ T lymphocytes regulate survival of DC-like cells. CD56+ PBMCs (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 20 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with bisphosphonate (10 or 30μM) plus IL-2. Cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface CD14 (DC-like cells; A) or TCRVδ2 (γδ T lymphocytes) and CD3 (all T lymphocytes; B). Frames point out DC-like cells. Arrows point out Vδ2− and CD3− cells (ie, NK cells) producing IFN-γ. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

In replete CD56+ PBMCs, zoledronate was more potent in inducing IFN-γ production in TCRVδ2+ γδ T lymphocytes (Figure 4B top panel; P < .05). However, a substantial TCRVδ2-negative population also produced IFN-γ in response to zoledronate (Figure 4B). This IFN-γ–producing population also lacked CD3 (Figure 4B bottom panel) and could thus be identified as NK cells (CD56+CD3−). To further characterize and identify CD56+CD3− cells as NK cells, we performed staining of NKp46 (CD335), which is a member of the natural cytotoxicity receptor family and considered to be a universal human NK cell marker.33 We found that CD3− cells were positive for NKp46 (supplemental Figure 2), irrevocably demonstrating that they were NK cells.

As an alternative to separation with microbeads, FACS of PBMCs also was performed. Supplemental Figure 3A demonstrates that cocultures of NK cells and CD56+ DC-like cells prepared by FACS mount similar synergistic IFN-γ responses to zoledronate plus IL-2. In addition, synergistic up-regulation of IL-1β production is shown (supplemental Figure 3B).

To test whether zoledronate-induced IFN-γ production in NK cells depends on γδ T lymphocytes, which have recently been shown to costimulate NK cell cytotoxicity,23 we examined zoledronate-induced intracellular IFN-γ in NK cells in replete CD56+ PBMCs and in T cell–depleted CD56+ PBMCs (CD56+CD3−) in a time- and dose-dependent manner. In replete and in T cell–depleted CD56+ PBMCs, IL-2 alone failed to induce substantial IFN-γ production (Figure 5). In replete CD56+ PBMCs, IL-2 in combination with the lower dose of zoledronate (10μM) induced modest IFN-γ production in both γδ T lymphocytes and NK cells already on day 1. On day 2, IFN-γ production was significantly enhanced in γδ T lymphocytes but almost completely silenced in NK cells. IL-2 in combination with the higher dose of zoledronate (30μM) induced strong IFN-γ production in both γδ T lymphocytes and NK cells already on day 1, whereas IFN-γ production seemed to decline in γδ T lymphocytes on day 2 and was again silenced in NK cells (Figure 5). In the absence of T lymphocytes, including γδ T lymphocytes, DC-like cells (arrows) survived and NK cell IFN-γ production was not silenced on day 2 but increased in a time-dependent and zoledronate dose-dependent manner (frames).

γδ T cell–dependent elimination of DC-like cells terminates NK cell IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate. CD56+ PBMCs or CD56+CD3− PBMCs (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with bisphosphonate (10 or 30μM) plus IL-2. On days 1 and 2, cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface TCRVδ2 (γδ T lymphocytes). Arrows point out DC-like cells surviving in the absence but not in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes. Frames point out NK cells that terminate IFN-γ production in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes but continue to produce IFN-γ in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

γδ T cell–dependent elimination of DC-like cells terminates NK cell IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate. CD56+ PBMCs or CD56+CD3− PBMCs (2 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with bisphosphonate (10 or 30μM) plus IL-2. On days 1 and 2, cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface TCRVδ2 (γδ T lymphocytes). Arrows point out DC-like cells surviving in the absence but not in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes. Frames point out NK cells that terminate IFN-γ production in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes but continue to produce IFN-γ in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

To exclude the possibility that zoledronate-induced disappearance of DC-like cells was mediated by CD56+ αβ T cells, we also performed experiments with CD56+ PBMCs that had been depleted of CD56+ αβ T cells but still contained CD56+ γδ T lymphocytes. Supplemental Figure 4 shows that zoledronate-induced disappearance of DC-like cells also occurred in the absence of CD56+ αβ T cells.

Downstream depletion of prenyl pyrophosphates resulting in caspase-1 activation, and maturation of IL-18 and IL-1β mediates zoledronate-induced NK cell activation

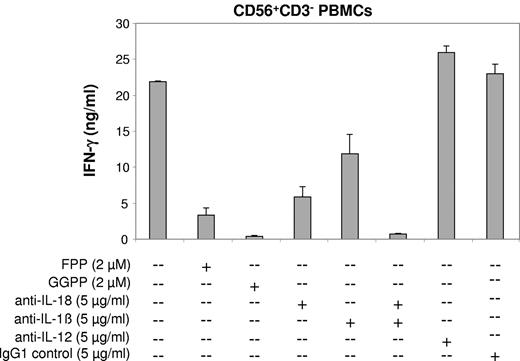

Zoledronate inhibits the mevalonate pathway before divergence of the cholesterol biosynthesis and protein prenylation branch (Figure 1B). To investigate the specificity of zoledronate-induced NK cell IFN-γ production, and to distinguish the relative importance of the various branches of the mevalonate pathway, cultures of CD3-depleted CD56+ PBMCs, which consist of NK cells and DC-like cells only, were treated with zoledronate plus IL-2 and concomitantly supplemented with the prenyl pyrophosphates FPP and GGPP. As shown in Figure 6, FPP strongly effected (P < .05) and GGPP almost prevented the IFN-γ response induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 (P < .01).

Abrogation of the zoledronate-induced NK cell IFN-γ response by prenyl pyrophosphate supplementation or cytokine neutralization. CD56+CD3− PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) solely consisting of NK cells and DC-like cells were stimulated with zoledronate (30μM) plus IL-2 (100 U/mL) in the presence or absence of prenyl pyrophosphates (FPP, GGPP), neutralizing antibodies (all IgG1), or IgG1 control antibody. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Abrogation of the zoledronate-induced NK cell IFN-γ response by prenyl pyrophosphate supplementation or cytokine neutralization. CD56+CD3− PBMCs (1 × 106/mL) solely consisting of NK cells and DC-like cells were stimulated with zoledronate (30μM) plus IL-2 (100 U/mL) in the presence or absence of prenyl pyrophosphates (FPP, GGPP), neutralizing antibodies (all IgG1), or IgG1 control antibody. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Depletion of prenyl pyrophosphates such as GGPP can lead to the activation of caspase-1.34,35 Caspase-1 cleaves the proforms of IL-18 and IL-1β to generate the mature, bioactive cytokines,36,37 both of which are well known for their ability to enhance IFN-γ production.33,38,39 We found that antibodies neutralizing IL-18 bioactivity strongly reduced IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 in cultures of CD56+CD3− PBMCs (Figure 6; P < .01). To a somewhat lower degree, neutralization of IL-1β inhibited IFN-γ production (P < .05). Moreover, concomitant neutralization of both IL-18 and IL-1β almost abolished IFN-γ production (Figure 6; P < .01). IL-12 is a major IFN-γ–inducing cytokine.10,33 In our cytokine analyses, IL-12p70 was undetectable in supernatants of CD56+ PBMC cultures stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2 (data not shown). In addition, IL-12p70–neutralizing antibodies did not result in the inhibition of IFN-γ production (Figure 6), indicating that IL-12 is not involved.

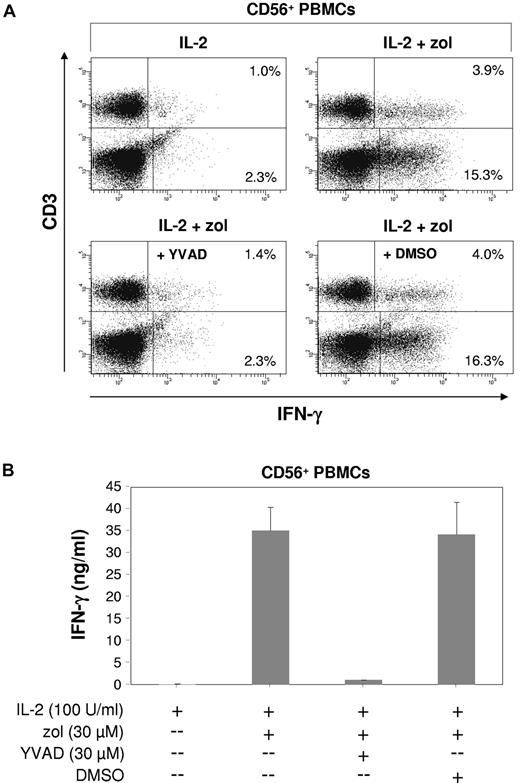

Because both IL-18 and IL-1β require caspase-1 for activation,40 we also tested the effects of the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD.41 YVAD alone was capable of abrogating zoledronate-induced intracellular IFN-γ production not only in NK cells but also in γδ T lymphocytes (Figure 7A; P < .01), whereas the DMSO solvent control had no effect. As a consequence, the total level of IFN-γ in culture supernatants was reduced by > 90% (Figure 7B; P < .01). Data shown in Figure 7A also indicated that NK cells can contribute substantially to the total IFN-γ produced in response to zoledronate plus IL-2.

Innate lymphocyte IFN-γ response induced by zoledronate depends on endogenous caspase-1. (A) CD56+ PBMCs (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 20 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (30μM) plus IL-2 in the presence or absence of the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD at 30μM (or DMSO solvent control). Cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface CD3. (B) IFN-γ levels were determined in culture supernatants. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Innate lymphocyte IFN-γ response induced by zoledronate depends on endogenous caspase-1. (A) CD56+ PBMCs (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 20 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (30μM) plus IL-2 in the presence or absence of the caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD at 30μM (or DMSO solvent control). Cells were stained for intracellular IFN-γ and for surface CD3. (B) IFN-γ levels were determined in culture supernatants. One of 3 independent experiments is shown.

Finally, we examined whether zoledronate regulates natural cytotoxicity of NK cells. Because we knew from previous experiments that zoledronate effects depended on DC-like cells, we tested the cytotoxicity of CD3−CD56+ PBMCs, that is, NK cells and DC-like cells, against K562 target cells at a ratio of 10:1 (supplemental Figure 5A). Natural cytotoxicity of NK cells costimulated by DC-like cells was already high and resulted in the elimination of ∼ 50% of K562 target cells (supplemental Figure 5B). After coculture, residual target cells also were analyzed for phosphatidylserine exposure (supplemental Figure 5C). In contrast to zoledronate, IL-2 alone further enhanced apoptosis of target cells. The combination of IL-2 and zoledronate resulted only in a modest increase compared with IL-2 alone. These findings indicated that in the absence of γδ T cells and presence of DC-like cells the major effect of zoledronate on IL-2–primed NK cells is the induction of IFN-γ.

Discussion

Our results provide the first evidence that zoledronate, the most potent bisphosphonate currently available, can induce IFN-γ production in IL-2–primed NK cells in a DC-like cell-dependent manner. The contribution of NK cells to the overall IFN-γ produced in response to zoledronate was substantial. Although zoledronate could induce NK cell activation even in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes, we also obtained evidence that γδ T lymphocytes could regulate the NK cell response to zoledronate, both positively and negatively. Early NK cell IFN-γ production was enhanced in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes (Figure 5), consistent with a recent report23 showing that γδ T lymphocytes can costimulate NK cell activation. In that report, γδ T lymphocytes enhanced the cytotoxicity of NK cells primed by immobilized human IgG1. In accordance with the same report, we also observed that zoledronate induced cytotoxicity against CD56+ DC-like cells in the presence of γδ T lymphocytes and thus induced the premature termination of the NK cell response (Figure 5), which strictly depended on these DC-like cells (Figure 3A). In contrast, in the absence of γδ T lymphocytes, CD56+ DC-like cells survived and maintained NK cell IFN-γ production (Figure 5).

γδ T cell–independent NK cell activation depended on DC-like cell-derived IL-18 and IL-1β, because neutralization of these 2 cytokines almost abolished NK cell IFN-γ production (Figure 6). Both IL-18 and IL-1β are produced as proforms by myeloid cells.38 Active caspase-1 is required in these cells to enzymatically cleave the proforms for the subsequent release of bioactive, mature IL-18 and IL-1β.40 Accordingly, we found that the specific caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD41 strongly inhibited zoledronate-induced IFN-γ production in NK cells (Figure 7A). The potential of IL-18 and IL-1β to synergize with IL-2 for the induction of IFN-γ in NK cells is well established.33,38,42,43

Downstream depletion of endogenous prenyl pyrophosphates was responsible for the zoledronate-induced NK cell response, because we observed that addition of FPP strongly and GGPP almost completely inhibited NK cell IFN-γ production (Figure 6). It has been demonstrated previously that depletion of the isoprenoid pyrophosphates FPP and GGPP (Figure 1B) can result in the activation of caspase-1.34 In the absence of appropriate activation signals, isoprenoids prevented the activation of caspase-1 by suppressing autoprocessing of caspase-1. Conversely, when isoprenoid formation was inhibited, the suppression of caspase-1 autoprocessing was abrogated resulting in caspase-1 activation.34 Likewise, in our work zoledronate-mediated inhibition of isoprenoid formation resulted in caspase-1 activation and in the release of mature, active IL-18 and IL-1β (Figures 6–7). The emerging mechanism of zoledronate-induced activation and regulation of IL-2–primed NK cells is summarized in supplemental Figure 6.

Our current observations are corroborated by our recent finding that statins also can induce NK cell activation.25 Statins, which are primarily used to control hypercholesterolemia, also have been proposed as anticancer agents.44 In contrast to bisphosphonates, which inhibit FPP synthase, statins inhibit hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, the first committed step of the mevalonate pathway (Figure 1B). Collectively, our observations indicate that inhibition of the mevalonate pathway for protein prenylation either mediated by the bisphosphonate zoledronate (this study) or by statins such as simvastatin25 is also a potent signal for NK cell activation. It may therefore be of interest to examine the role of NK cells in bisphosphonate- and statin-based cancer therapy and chemoprevention.

The translation of isoprenoid pyrophosphate deprivation into caspase-1–mediated inflammation, which we observed here during zoledronate-induced inhibition of mevalonate metabolism, has recently been observed in mevalonate kinase deficiency (MKD), a rare hereditary autoinflammatory syndrome.45 In MKD, the enzyme is inactive because of mutations of the encoding gene. Lack of mevalonate kinase, the second enzyme of the mevalonate pathway (Figure 1B), results in GGPP deprivation followed by Nalp3-dependent caspase-1 activation and maturation of bioactive IL-1β. The inflammatory phenotype of MKD, which includes periodic fevers, is consistent with many of the well known biologic effects of IL-1β.46

Together with our previous work,24,25 the present data suggest that CD56+ DC-like cells may indeed be the preferred accessory cells for the activation of innate lymphocytes such as γδ T lymphocytes and NK cells. CD56+ DC-like cells expressed substantial levels of HLA-ABC, HLA-DR, CD54, CD80, and CD86 (Figure 1C). During short-term culture all these markers were strongly and rapidly up-regulated in the absence of exogenous stimuli (Figure 1C). In the present work, we also show that CD56+ DC-like cells express CCR2 but not CD16 (Figure 2) and can therefore be classified as differentiating inflammatory DC-like cells.32 Among CD56+ PBMCs, CD7 is a useful marker to distinguish CD56+ DC-like cells (CD7−) from CD56+ lymphocytes (CD7+; Figure 2), also confirming that CD56+ DC-like cells are of myeloid origin and not related to NK cells.27

A severe toxic effect of intravenous bisphosphonates is osteonecrosis of the jaw.47 The risk of development of osteonecrosis of the jaw is dependent on cumulative dose and potency of the agent. The risk is clearly increased for zoledronate, which is ∼ 1000-fold more potent than pamidronate.1 It will be important to clarify whether zoledronate-mediated NK cell activation, as reported here, can contribute to the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw, which can be considered an inflammatory condition associated with substantial leukocyte infiltration.48 Infiltrating leukocytes may encounter high concentrations of bisphosphonate, which have been shown previously to accumulate in the resorption space, where they may reach 0.1-1mM.49

In summary, we have shown that the potent bisphosphonate zoledronate not only induces γδ T-cell activation but can also induces NK cell activation. The DC-like cell-dependent effect is because of zoledronate-mediated inhibition of isoprenoid formation, resulting in caspase-1 activation and maturation of active IL-18 and IL-1β. The two cytokines induce IFN-γ production in IL-2–primed NK and γδ T cells. γδ T lymphocytes can initially enhance NK cell IFN-γ production but then mediate DC-like cell elimination and termination of the NK cell response. Our findings also indicate that caspase-1–mediated cytokine maturation is the central mechanism underlying innate lymphocyte activation in response to zoledronate. The colocalization of NK cells and DCs in either secondary lymphoid organs or in inflammatory lesions is well established. At these sites, they can be exposed to zoledronate because of the systemic administration of the bisphosphonate via the intravenous route. In clinical studies of zoledronate-based cancer therapy, immune monitoring should therefore not only focus on γδ T lymphocytes but also on NK cells, both in terms of antitumor responses and with respect to a potential role of NK cells in the development of osteonecrosis of the jaw.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Walter Nussbaumer (Central Institute for Blood Transfusion) for providing residual buffy coats as study material and Sieghart Sopper (Innsbruck Flow Cytometry Unit) for cell sorting. They also thank Andrea Rahm and Florina Iliut for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the COMET K1 Center Oncotyrol (to M.T.). Oncotyrol is funded by the Federal Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology; the Federal Ministry of Economics and Labor/Federal Ministry of Economy, Family and Youth; and the Tiroler Zukunftsstiftung. The authors appreciate the participation of the TILAK hospital holding company, who serves as a partner in the Oncotyrol research program.

Authorship

Contribution: M.T., O.N., and G.G. designed research; O.N., G.G., and H.G. performed experiments; M.T., O.N., and G.G. analyzed results and prepared figures; and M.T. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.T. is an expert advisor of the preclinical board of CELLMED (last activity December 2009). M.T. has filed a patent application that concerns the use of Candida IgG for cancer patient prognosis. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martin Thurnher, Cell Therapy Unit, Department of Urology, Innsbruck Medical University and K1 Center Oncotyrol, Innrain 66a, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; e-mail: martin.thurnher@i-med.ac.at.

References

Author notes

O.N. and G.G. contributed equally to this study.