Abstract

In adult mammals, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the bone marrow (BM) and are maintained in a quiescent and undifferentiated state through adhesive interactions with specialized microenvironmental niches. Although junctional adhesion molecule-C (JAM-C) is expressed by HSCs, its function in adult hematopoiesis remains elusive. Here, we show that HSCs adhere to JAM-B expressed by BM stromal cells in a JAM-C dependent manner. The interaction regulates the interplay between HSCs and BM stromal cells as illustrated by the decreased pool of quiescent HSCs observed in jam-b deficient mice. We further show that this is probably because of alterations of BM stromal compartments and changes in SDF-1α BM content in jam-b−/− mice, suggesting that JAM-B is an active player in the maintenance of the BM stromal microenvironment.

Introduction

The junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) are a subset of the immunoglobulin (Ig) protein superfamily and are characterized by the presence of both a type V and a type C2 extracellular Ig domain. JAMs and related molecules have been involved in the control of interendothelial junctions and leukocyte transendothelial migration through homotypic and heterotypic interactions.1-5 JAM-B has been previously shown to interact with JAM-C and contributes to leukoendothelial and interendothelial cell-cell adhesion.6,7 In mice, JAM-B expression is restricted to endothelial cells whereas JAM-C is expressed by various cell types including endothelial,1,2 fibroblastic,8 and smooth muscle cells.9 Moreover, we have recently shown that JAM-C expression in lymph node fibroblastic cells is required for constitutive secretion of several chemokines such as SDF-1α.10 Recently, expression of several JAM family members, such as JAM-A, JAM-C, JAM4, or ESAM, has been reported in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), although a function for these proteins in hematopoiesis remains unknown.11-16

In adult mammals, HSCs are rare cells mainly located in the bone marrow (BM) and able to generate all mature blood cells. In mice, HSCs are comprised within the LSK compartment as defined by the LineageNeg c-kitHi Sca-1Hi (LSK) phenotype; the LSK compartment can be further subdivided using additional markers such as CD34, CD150, or CD48. Indeed, CD34Neg CD135Neg LSK, or Thy-1Lo LSK17,18 and CD150Pos CD48Neg LSK cells19 have been shown to contain, respectively, around 20% and 50% of HSCs with long-term hematopoietic reconstitution potential (LT-HSCs). Because HSCs give rise to mature hematopoietic cells, including immune cells, their replacement must be adjusted to homeostatic or stress conditions such as infections, inflammation, or blood loss, and their expansion must be controlled to avoid exhaustion through inappropriate proliferation and differentiation. This is possible by the coordinated regulation of quiescence, self-renewal, and differentiation of HSCs through appropriate signals delivered by functional microenvironments called niches.20-22 HSCs are restrained in these specialized microenvironments by interactions mediated by adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors expressed by HSCs, such as VLA-4 or CXCR4, with their ligands present within the BM microenvironment. Other signaling pathways controlled by growth factors and their receptors expressed on HSCs, such as angiopoietin-1 and TIE2, SCF and KIT, Thrombopoietin and MPL, have also been involved in HSC maintenance and retention in BM niches.23,24 Whether the JAM family members expressed on HSCs also contribute to this signaling network has not been addressed so far.

When necessary, HSCs enter the cell cycle to maintain BM cellularity and replenish peripheral blood in a process called mobilization, which can be induced using various hematopoietic growth factors, cyclophosphamide in combination with G-CSF (Cy/G-CSF), or intravenous injections of the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 or plerixafor.22,25-28 Whereas the central role of the interaction between SDF-1 and CXCR4 has been established after years of clinical use of various mobilization regimens, signals contributing to HSC retention versus mobilization are only partially understood.

Here, we show that HSCs interact with, and adhere to, JAM-B–expressing BM stromal cells. The binding of JAM-B to HSCs is dependent on JAM-C expression by hematopoietic cells and is lost during HSC differentiation. Such an interaction contributes to the signaling pathways occurring between HSCs and BM stromal cells as illustrated by the exacerbated response to mobilizing agents and the decrease in the quiescent pool of HSCs observed in jam-b deficient mice. We further show that this is most probably because of alterations of BM stromal cell composition in jam-b deficient mice and changes in SDF-1α BM content.

Methods

Mice

Generation and phenotype of jam-c deficient mice were previously described.29 Because jam-c deficient males are infertile, the colony is maintained by interbreeding of jam-c+/− mice maintained and back-crossed for > 8 generations on C57Bl/6 background. C57BL/6 and C57BL/6-CD45.1 were purchased from Janvier Laboratory and Charles River Laboratories, respectively. All experiments were performed in agreement with the French Guidelines for animal handling and were approved by the Inserm ethical committee.

Generation of jam-b deficient mice

A jam-b gene fragment containing exon 5 was flanked by loxP recognition sites for Cre recombinase. Within the loxP-flanked region, a murine jam-b cDNA fragment (codons 165-298, PEY…SFII*) followed by the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal (pA) was fused to a BspE1 site in exon 5. The construct also contained a neomycin resistance cassette surrounded by frt sites enabling Flp recombinase-mediated removal, as well as long (9 kb, 5′) and short (1.65 kb, 3′) arms for homologous recombination. Electroporated and G418-selected embryonic stem cell clones were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization and PCR. For PCR screening, a primer pair, derived from exon 4 and the intronic jam-b sequence flanking the 5′ loxP site, amplified a 345-bp band from WT chromosomes and a 450-bp band from transgenic chromosomes (primers were 5′-AGACCGTGCTGAGATGATAGA-3′ and 5′-CCGAAGGAAGTGTCTAGTAAT-3′). Three independent lines were generated and maintained in a mixed 129Sv × C57BL/6 background. jam-b deficient mutants were generated by cross-breeding with the PGK-Cre line followed by interbreeding jam-bKO/+ heterozygotes. Mice used in the present study were back-crossed for more than 6 generations on C57BL/6 background.

Antibodies for flow cytometry

The following antibodies used for flow cytometry and cell sorting were purchased from eBioscience or Biolegend: biotin anti-CD4, CD8, CD3, DX5, CD11C, CD19, B220, TER119, CD11B and Gr1 (Lineage cocktail), CD51, Streptavidin–Pacific Blue or PE-Cy7 (BD Bioscience), cKit-APC or APC-eFluor780 (clone 2B8 or ACK2), SCA-1-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone D7), CD34-FITC (clone RAM34), CD16/32-PECy7, CD150-APC (clone TC15-12F12.2), CD48-PECy7 (clone HM48.1), CD135-PE, CD31-APC (clone 390), CD45-APC-eFluor780, Ter119–Pacific Blue, CD19, CD11b, CD4, CD8 and CD45R-FITC, CD45.1-FITC and CD45.2-PE. The recombinant soluble forms of mouse JAM-B (sol-JAM-B) and JAM-C (sol-JAM-C; R&D Systems) were revealed with PE-goat-anti–human FC secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Polyclonal rabbit anti–mouse JAM-B antibody (pAb 829), rabbit anti–mouse JAM-C antibody (pAb 501), and monoclonal antibodies (PS2/8 and R1/2) directed against VLA-4 were produced in the laboratory. Texas Red– or PE-conjugated goat-anti–rabbit (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) were used as secondary antibodies.

BM stroma analysis

Femurs and tibias of 6 mice were dissected and crushed with a pestle before digestion in RPMI medium containing collagenase (collagenase 2mg/mL [Sigma-Aldrich]; 2% FCS) for 45 minutes. Cells were washed in RPMI containing 2% FCS, and further washed in PBS containing 5mM EDTA. Bone fragments were removed by filtration through a 70-μm cell stainer filter (BD Bioscience) and erythrocytes were lysed by incubation with ACK solution for 2 minutes at room temperature.

Histology and imaging

Antibodies against PECAM-1 (clone 390, Allocyanin-conjugated; Ebioscience), JAM-B (polyclonal rabbit anti–mouse p829), α smooth muscle actin (αSMA, Cy3-conjugated; Sigma-Aldrich), CD150 (clone TC15-12F12.2, Allocyanin-conjugated; Biolegend), CD48 (clone HM48.1, FITC-conjugated; Biolegend), Gr1, B220, CD3, CD11b, and CD41 (FITC-conjugated; Biolegend) were used for immunofluorescent stainings. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described.7,19,30 Briefly, 20-mm-thick sections were transferred to adhesive-coated slides with the CryoJane Tape-Transfer system according to the manufacturer's protocol (Instrumedics). Bone sections (after fixation in methanol) were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with a blocking solution (PBS, 2% BSA, 1% donkey serum, 1% FCS). After washes, bone sections were stained. All secondary probes were from Invitrogen and Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories. All images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM510 Meta or a Leica SP5X (Leica Microsystems) confocal microscope. Quantification was achieved using ImageJ Version 1.37 (NIH) software by the analysis of staining obtained on 8-10 sections by bone of 3 bones. Results were expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) measured for CD31 and JAM-B staining.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Femurs and tibias were collected and BM cells were flushed in PBS containing 1.25mM EDTA and 2% FCS. BM cells were stained in this medium supplemented with normal rat serum, 2.4G2 supernatant, and normal goat serum when necessary. For staining with the recombinant soluble forms of JAM-B (sol-JAM-B) or JAM-C (sol-JAM-C), cells were incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes with 1 μg/mL recombinant soluble molecules in the presence of normal goat serum. After a wash, cells were incubated with goat–anti-hFc secondary antibody coupled to PE for 30 mn at 4°C, washed, and incubated with biotin lineage cocktail for 10 minutes at room temperature with agitation. Finally BM cells were stained with anti-CD117, Sca-1, CD150, CD135, CD34, and CD16/32 and the Pacific Blue–Streptavidin to reveal Lineage Positive cells. Vivid dye was used to exclude dead cells (Invitrogen). Flow cytometry analysis and sorting were performed using BD-LSR2 SORP (laser 405, 488, 561, and 633; BD Bioscience) and FACS-ARIA 2 (BD-Bioscience) cytometers. Results were analyzed using BD-DIVA Version 6.1.2 software (BD Bioscience) or FlowJo Version 7.6.2 (TreeStar) software.

For purification and sorting of progenitors cells, BM cells from wt CD45.1 mice (CD45.1 BM cells) were stained with biotin-conjugated Lineage combination. LinPos cells are depleted using sheep anti–rat beads (Dynal; Invitrogen). The remaining LinNeg cells were stained as described in the preceding paragraph. LSK populations were purified by cell sorting using a FACS-ARIA with > 95% purity.

To analyze BM stromal cells, BM cells were stained with CD45-APC-eFluor780 and CD45Pos cells were depleted using sheep anti–rat beads (Dynal, Invitrogen). The remaining CD45Neg cells were first stained with rabbit anti–JAM-B polyclonal antibody (p829) revealed by a goat-anti–rabbit-PE (Jackson Immunology). Cells were then stained with anti-CD4, CD8, CD45R, CD11b, and Gr1-FITC, anti-TER119–Pacific Blue, CD51-biotin, CD31-APC, Sca-1-PerCP-Cy5.5. CD51staining was revealed with a PE-Cy7-Streptavidin.

Cell-cycle analysis

BM progenitors were enriched as previously described and stained with cKit–APC-eFluor750, CD150-APC, Sca-1–PerCP-Cy5.5, and CD48-PECy7. The biotin-conjugated lineage combination was revealed with AlexaFluor 594–streptavidin (Invitrogen). After extracellular staining, cells were permeabilized, fixed, and stained with anti–Ki67-FITC MoAb (BD Bioscience) and DAPI as previously described.31

BM transfer assays

For transplantation experiments, lethally irradiated (10 Gy) mice (C57BL/6, CD45.2) were injected with 4000 sorted LinNeg CD117hi Sca-1hi cells, LinNeg CD117hi Sca-1hi sol-JAM-BPos cells, or LinNeg CD117hi Sca-1hi sol-JAM-BNeg cells through the retro-orbital vein, along with 1 × 105 host-type total BM cells to insure animal survival. Donor cell (CD45.1Pos cells) and host cell (CD45.2Pos cells) frequency was analyzed by flow cytometry once a week for at least 2 months.

For chimeric mouse experiment, lethally irradiated (10 Gy) mice (C57Bl/6, CD45.1) received 5 million total BM cells from jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ CD45.2 mice. These chimeric mice were used for 5FU assay, at least 12 weeks after BM graft to ensure stable hematopoietic reconstitution. Before 5FU assay, donor cell (CD45.2Pos cells) and host cell (CD45.1Pos cells) frequency was analyzed by flow cytometry; 12 weeks after transfer, > 95% of cells were from donor origins.

For engraftment assay, jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ CD45.2 mice were lethally irradiated and grafted with 4000 CD45.1+ LSK cells. Recipient mice survival was followed and BM engraftment examined by monitoring donor (CD45.1+ cells) and host cell (CD45.2+ cells) frequency in the blood. After lethal irradiation, mice were maintained on water containing neomycin sulfate 1g/500mL for 2 weeks.

BM mobilization assays

jam-b deficient and control mice were bled to evaluate leukocyte distribution in the blood at steady state 2 weeks before experiment. Mobilization was then induced either with injection of AMD3100 (3 mg/kg), an antagonist of CXCR4, or with cyclophosphamide (4 mg) and rhG-CSF (5 μg at d0, d1, and d2) as previously described.27,28 Mice were killed 3 hours after AMD-3100 injection or 1 day after the last injection of rhG-CSF. Mobilization was evaluated with the frequency of myeloid cells (Mac1Pos) and granulocytes (Mac1PosGr1PosF4/80Neg) into blood and progenitor mobilization was studied with CFU-C assay. Results were expressed as mobilization index using the ratio between the percentage of cells after and before mobilization.

HSC exhaustion after 5FU treatment

jam-b deficient and control mice were injected intraperitoneally once a week with 5FU (120 mg/kg). Mice survival was followed on a daily basis until 25 days after the first 5FU injection. In some experiments, animals received a single injection of 5FU (d0) and were killed at day 3 for BM stroma analysis

Colony-forming assay

Peripheral blood and BM were treated with ACK (Gibco; Invitrogen) to lyse red blood cells. Blood cells (1 × 105) or 1 × 104 BM cells were seeded in methylcellulose medium following the manufacturer's instructions (StemCell Technologies).

ELISA assays

Femurs and tibias from jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ mice were collected and BM cells were flushed in 2 mL of PBS. Quantities of SCF and SDF1-α were determined by ELISA following manufacturer's instruction (R&D Systems) and results were expressed as relative concentration per milliliter.

Adhesion assays

Plates (96-well flat) were coated overnight at 4°C with 30μg/mL of recombinant sol-JAM-B, sol-JAM-C, bovine recombinant Fibronectin (Sigm-Aldrich), or Laminin (Sigma-Aldrich). Wells were washed twice in PBS 1X and saturated with HBSS 5% BSA for 1 hour at 37°. Then, 5 × 105 LinNeg cells preactivated or not with PMA (50 ng/mL) and resuspended in 200 μl of RPMI medium (2% of FCS) were allowed to adhere for 1 hour. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS and adherent cells were removed by strong pipetting in PBS 1.25mM EDTA 2% FCS. The phenotype of adherent cells was determined using anti-CD117, Sca-1, CD34, CD16/32, and streptavidin coupled to Pacific Blue to exclude any residual mature cells contaminating the LinNeg preparation. Absolute numbers were measured using the HTS coupled to the BD-LSR2 SORP (BD Bioscience).

For adhesion assays using the OP9 stromal cell line, stromal cells were plated on 96-well flat bottom plates, at the concentration of 5000 cells/well 1 day before the assay. LinNeg BM cells (5 × 105) obtained as previously described were cocultured for 1 hour with OP9 stromal cells, in the presence of the recombinant sol-JAM-B protein (10 μg/mL) or in control condition. Plates were washed 3 times with PBS. Adhesion was quantified as previously described.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined with nonparametric Mann-Withney U test or 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest using Prism Version 5 software (Graphpad Software Inc).

Results

Long-term HSCs bind to JAM-B in a JAM-C–dependent manner

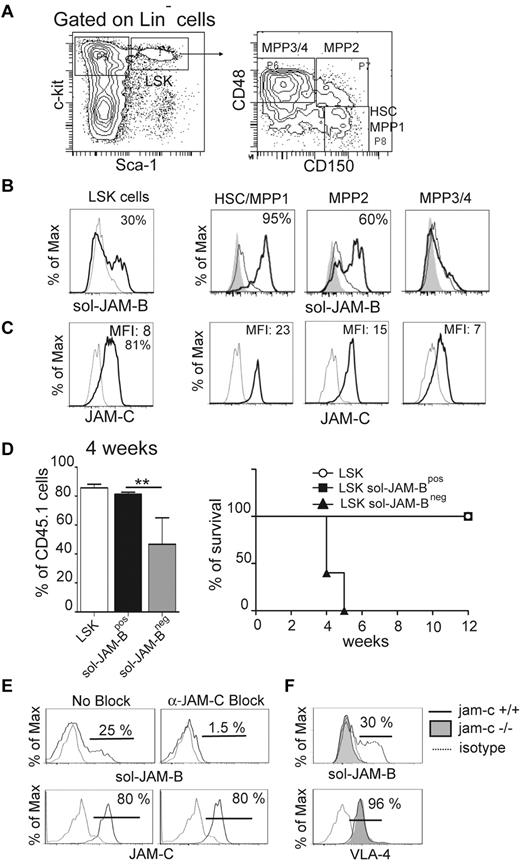

To explore the interaction between JAM-B and JAM-C within the murine BM microenvironment, we performed flow cytometry analysis to measure the extent of binding between BM progenitor cells and recombinant soluble JAM molecules. The gating strategy used to define the different immature hematopoietic subsets is shown in Figure 1A. Using a combination of Lineage, Sca-1, and c-Kit (LSK; CD117) antigen expression, together with the recombinant soluble JAM-B (sol-JAM-B) and JAM-C proteins (sol-JAM-C), we showed that 37% ± 6.3% of LSK cells costained positively for sol-JAM-B (Figure 1B) where no interaction between BM hematopoietic cells and sol-JAM-C was observed (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The binding of sol-JAM-B was not detected on the LinNeg CD117Hi Sca-1Neg cell population, known to contain common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and granulocyte monocyte progenitors (GMPs; supplemental Figure 1B). We then measured sol-JAM-B binding to specific cellular subsets within the LSK population using a combination of markers to distinguish HSC/MPP1 (Multipotent Progenitor 1; CD150PosCD48Neg) and more differentiated multipotent progenitors (termed MPP2 to MPP4 according to their stage of differentiation).19,31 A correlation was observed between the ability to bind to JAM-B and the differentiation stages of progenitor cells. Indeed, > 95% of undifferentiated HSCs/MPP1 cells showed binding to sol-JAM-B (Figure 1B); binding was reduced to 60% for more differentiated MPP2 cells and even further reduced for MPP3/4 cells. We then tested whether sol-JAM-B binding to hematopoietic cells varied accordingly with hematopoietic expression of JAM-C, a known JAM-B counter-receptor. In agreement with a previous report by Praetor et al, homogenous expression of JAM-C was detected in LSK cells.13 When subsets of LSK cells were further analyzed, the staining intensity inversely correlated with the differentiation stage as illustrated by the decrease in MFI ratios from 23 to 7 for HSC/MPP1 versus MPP3/4 (Figure 1C). In addition, we found that the LSK fraction binding to sol-JAM-B was enriched in quiescent cells (G0; supplemental Figure 1C black bars), suggesting that sol-JAM-B binding is a marker of quiescent HSC that display the highest LT-HSC potential.

JAM-B interaction with HSC is JAM-C-dependent. (A) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the gating strategy used to define the hematopoietic progenitor subset. LSK cells are defined as LinNegScaPosc-KitPos cells and are further divided into three distinct populations on the basis of CD48 and CD150 expression as indicated. The most immature progenitors containing LT-HSC and MPP1 are defined as CD150PosCD48Neg LSK cells. (B) Histograms showing the binding of recombinant soluble JAM-B (black line) compared with sol-JAM-C (dashed line) or unstained cells (filled gray). Percentages of cells binding to sol-JAM-B are indicated. (C) Histograms showing JAM-C expression (black line) compared with control staining (dashed line). A rabbit polyclonal antibody was used and compared with the staining obtained with pre-immune serum. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) are indicated. (D) Left panel: Percentage of chimerism observed in the blood of lethally irradiated mice 4 weeks after engraftment with the indicated hematopoietic subsets. One representative experiment of 3 is shown (n = 6 mice/group; **P < .01). Right panel: Survival curves of mice engrafted with the indicated cells are shown. The survival curves of mice engrafted with total LSK and LSK sol-JAM-BPos are overlayed. (E) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the levels of sol-JAM-B binding or JAM-C expression on LSK cells in the absence or presence of blocking pAb. JAM-B binding to LSK is prevented by rabbit-anti JAM-C antibody. This experiment was realized on at least 6 independent mice. (F) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing JAM-B binding and VLA-4 expression on JAM-C deficient LSK cells. JAM-B binding and VLA-4 expression on LSK cells isolated from Jam-C deficient (filled gray) or control animals (plain line) are compared with control (dashed line). This experiment was realized on at least 4 independent Jam-C deficient mice and compared with control littermate mice.

JAM-B interaction with HSC is JAM-C-dependent. (A) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the gating strategy used to define the hematopoietic progenitor subset. LSK cells are defined as LinNegScaPosc-KitPos cells and are further divided into three distinct populations on the basis of CD48 and CD150 expression as indicated. The most immature progenitors containing LT-HSC and MPP1 are defined as CD150PosCD48Neg LSK cells. (B) Histograms showing the binding of recombinant soluble JAM-B (black line) compared with sol-JAM-C (dashed line) or unstained cells (filled gray). Percentages of cells binding to sol-JAM-B are indicated. (C) Histograms showing JAM-C expression (black line) compared with control staining (dashed line). A rabbit polyclonal antibody was used and compared with the staining obtained with pre-immune serum. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) are indicated. (D) Left panel: Percentage of chimerism observed in the blood of lethally irradiated mice 4 weeks after engraftment with the indicated hematopoietic subsets. One representative experiment of 3 is shown (n = 6 mice/group; **P < .01). Right panel: Survival curves of mice engrafted with the indicated cells are shown. The survival curves of mice engrafted with total LSK and LSK sol-JAM-BPos are overlayed. (E) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the levels of sol-JAM-B binding or JAM-C expression on LSK cells in the absence or presence of blocking pAb. JAM-B binding to LSK is prevented by rabbit-anti JAM-C antibody. This experiment was realized on at least 6 independent mice. (F) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing JAM-B binding and VLA-4 expression on JAM-C deficient LSK cells. JAM-B binding and VLA-4 expression on LSK cells isolated from Jam-C deficient (filled gray) or control animals (plain line) are compared with control (dashed line). This experiment was realized on at least 4 independent Jam-C deficient mice and compared with control littermate mice.

To establish that cells interacting with sol-JAM-B were LT-HSCs, sol-JAM-BPos, and sol-JAM-BNeg LSK subsets from CD45.1 mice were sorted and tested for their ability to reconstitute lethally irradiated CD45.2 recipient mice.32 Total CD45.1 LSK cells known to contain LT-HSCs were used as positive control. Reconstitution and chimerism were followed over time by monitoring the frequency of CD45.1 cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mouse. As expected, total LSK cells were able to reconstitute recipient mice between 2 and 12 weeks after transplantation (not shown). The same result was obtained using sol-JAM-BPos LSK cells. In contrast, few CD45.1Pos circulating cells were found in mice transplanted with sol-JAM-BNeg LSK cells 4 weeks after transplantation and all mice in this group died one week later (Figure 1D). Mice that received sol-JAM-BPos LSK cells survived more than 2 months after transplantation, indicating that the LT-HSCs are entirely included in the LSK subset binding to sol-JAM-B.

Another ligand of JAM-B is VLA-4 (α4β1integrin),6 which could allow for JAM-B binding to HSCs independently of JAM-C expression on these cells. To address this issue we used blocking antibodies directed against either JAM-C or VLA-4. Sol-JAM-B binding to LSK cells was prevented when cells were first incubated with the anti–JAM-C antibody whereas antibodies against VLA-4 (PS2/8, R1/2) or isotype control antibody had no effect (Figure 1E, supplemental Figure 2). To formally prove that JAM-B binding on LSK cells was JAM-C dependent, LSK cells isolated from jam-c−/− mice were tested for their ability to bind sol-JAM-B. The binding was lost when hematopoietic cells were isolated from jam-c−/− mice, although VLA-4 expression remained unchanged (Figure 1F), showing that JAM-C expression on hematopoietic cells is necessary for JAM-B interaction with LSK cells.

JAM-B interaction with LSK supports adhesion

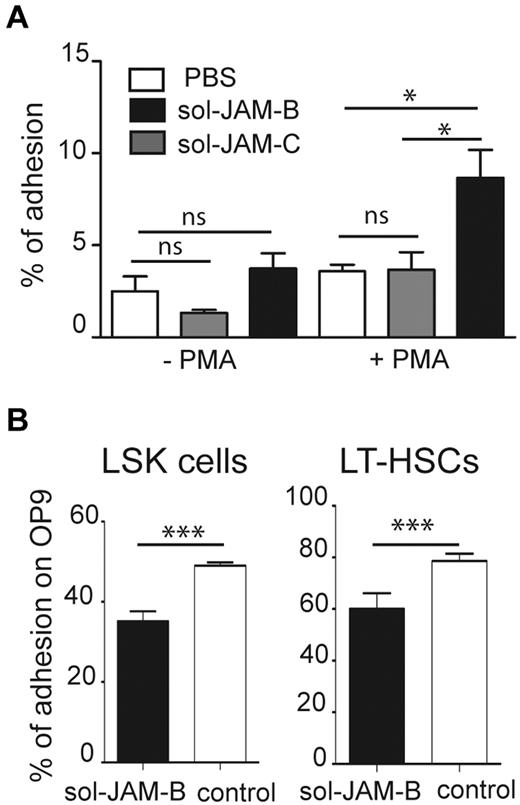

Having shown that sol-JAM-B binding is specific for an LSK subset containing LT-HSCs, we wondered whether this might have functional relevance for LSK adhesion within the BM microenvironment. Because adhesion of BM progenitors to fibronectin is enhanced by PMA treatment,33 we performed an adhesion assay using PMA-stimulated LinNeg cells on different substrates, and phenotyped cells that adhered to fibronectin (FN), laminin, sol-JAM-B, sol-JAM-C, or plastic support. No selective adhesion of progenitor or LSK cells was observed on laminin, sol-JAM-C, or plastic. In contrast, GMP cells specifically adhered to fibronectin and LSK cells were selectively enriched when sol-JAM-B was used as adhesive substrate (supplemental Figure 3). Such specific adhesion of LSK cells to JAM-B was only observed on PMA activation of LinNeg cells, indicating that the interaction is probably dependent on integrin activation (Figure 2A). Frequency of LSK cell adhesion to sol-JAM-C did not rise above the background levels observed on plastic support. To determine whether LSK cells bind to JAM-B expressed on BM stroma, we performed adhesion assays using the murine OP9 stromal cell line, which expresses JAM-B (not shown). More than 50% of LSK cells and > 75% of LT-HSCs, defined as CD34Neg LSK cells, adhered to the OP9 stromal cells. Adhesion of both cell subsets was reduced in the presence of the sol-JAM-B protein (Figure 2B), indicating that hematopoietic cell adhesion to stromal cells is partially JAM-B dependent.

HSC adhere to stromal cells in a JAM-B dependent manner. (A) Graph showing adhesion of nonactivated or PMA activated LinNeg progenitor cells to plastic support (PBS), coated recombinant soluble JAM-B (sol-JAM-B) or recombinant soluble JAM-C (sol-JAM-C). After 1 hour, adherent cells were detached and percentages of adherent LSK cells were determined and compared with the percentage of LSK cells in the input of LinNeg population. Results are expressed as percentage of adhesion. (B) Adhesion of the indicated subset to the bone marrow stromal cell line OP9 is shown. Purified LinNeg progenitor cells were left untreated (white bars) or pre-incubated with sol-JAM-B (black bars) before incubation with the OP9 cell monolayer. After 1 hour, adherent cells were detached and percentages of adherent cells determined. Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (***P < .001).

HSC adhere to stromal cells in a JAM-B dependent manner. (A) Graph showing adhesion of nonactivated or PMA activated LinNeg progenitor cells to plastic support (PBS), coated recombinant soluble JAM-B (sol-JAM-B) or recombinant soluble JAM-C (sol-JAM-C). After 1 hour, adherent cells were detached and percentages of adherent LSK cells were determined and compared with the percentage of LSK cells in the input of LinNeg population. Results are expressed as percentage of adhesion. (B) Adhesion of the indicated subset to the bone marrow stromal cell line OP9 is shown. Purified LinNeg progenitor cells were left untreated (white bars) or pre-incubated with sol-JAM-B (black bars) before incubation with the OP9 cell monolayer. After 1 hour, adherent cells were detached and percentages of adherent cells determined. Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments (***P < .001).

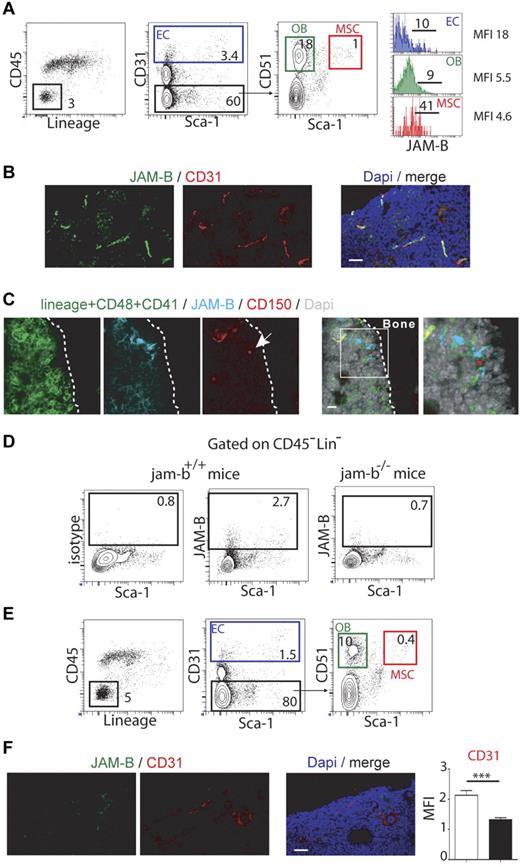

JAM-B is expressed on BM stromal cells

To address the in vivo relevance of JAM-B interaction with LSK cells, we determined the expression profile of JAM-B in BM hematopoietic and stromal cells by flow cytometry. Using cells extracted from collagenase digested bones, JAM-B expression was found only in the CD45Neg LinNeg stromal fraction, which was further analyzed for stromal subsets according to the gating strategy described in Figure 3A.34,35 Approximately 10% of endothelial cells (ECs) and osteoblasts (OBs), as respectively defined by the CD31Pos and CD31Neg Sca-1Neg CD51Pos phenotypes expressed JAM-B whereas > 40% of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs, CD31Neg Sca-1Pos CD51Pos) were positive (Figure 3A). This stromal distribution was further confirmed by immunofluorescence on BM sections. We found that JAM-B expression was closely associated with CD31Pos vascular structures, although the confocal resolution is not sufficient to rule out perivascular expression of JAM-B by mesenchymal cells surrounding the vascular conducts (Figure 3B, supplemental Figure 4). To determine whether HSCs were closely associated with JAM-BPos stromal cells in vivo, we performed immunohistochemistry on bone sections using CD150, JAM-B, and a combination of Lin/CD41/CD48 markers. As shown in Figure 3C, LinNeg CD48Neg CD41Neg CD150Pos HSCs were found in contact with JAM-BPos stromal cells, demonstrating that JAM-B is expressed on cells of the HSC niches in situ.

Bone marrow microenvironmental defects in jam-b deficient mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry profiles used to define the bone marrow stromal subsets are shown (EC indicates endothelial cell; OB, osteoblast; and MSC, mesenchymal stem cell). Histograms in the left panel show the expression profiles of JAM-B on the indicated subsets. Percentages are indicated on the gates. Bones from 6 mice were pooled and 1 representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections from control mice stained with the indicated markers are shown. High expression of JAM-B is found in close association with CD31 positive structures. (C) Confocal images showing a LinNegCD48Neg CD41NegCD150Pos cell (HSC, single red cell, arrow) in contact with JAM-BPos stromal structure (blue). (D) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing JAM-B and Sca-1 expression by bone marrow stromal cells defined as CD45NegLinNeg cells in wild-type littermate and jam-b deficient mice. (E) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the bone marrow stromal composition of jam-b deficient mice. The percentages of ECs, OBs, and MSCs are shown. There is a 2-fold reduction in the proportions of ECs, OBs, and MSCs compared with control mice shown in panel A. Bones from 6 mice were pooled and one representative experiment is shown. Results from 2 additional independent experiments are provided in supplemental Figure 6. (F) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections from jam-b deficient mice stained with the indicated markers are shown. No signal is observed for JAM-B and decreased signal for CD31 is found compared with wild type sections shown in panel B. The graph in the left panel show a quantification of the CD31 staining observed on 8 femoral sections of control littermate (white bar) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar).

Bone marrow microenvironmental defects in jam-b deficient mice. (A) Representative flow cytometry profiles used to define the bone marrow stromal subsets are shown (EC indicates endothelial cell; OB, osteoblast; and MSC, mesenchymal stem cell). Histograms in the left panel show the expression profiles of JAM-B on the indicated subsets. Percentages are indicated on the gates. Bones from 6 mice were pooled and 1 representative experiment of 3 is shown. (B) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections from control mice stained with the indicated markers are shown. High expression of JAM-B is found in close association with CD31 positive structures. (C) Confocal images showing a LinNegCD48Neg CD41NegCD150Pos cell (HSC, single red cell, arrow) in contact with JAM-BPos stromal structure (blue). (D) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing JAM-B and Sca-1 expression by bone marrow stromal cells defined as CD45NegLinNeg cells in wild-type littermate and jam-b deficient mice. (E) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the bone marrow stromal composition of jam-b deficient mice. The percentages of ECs, OBs, and MSCs are shown. There is a 2-fold reduction in the proportions of ECs, OBs, and MSCs compared with control mice shown in panel A. Bones from 6 mice were pooled and one representative experiment is shown. Results from 2 additional independent experiments are provided in supplemental Figure 6. (F) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections from jam-b deficient mice stained with the indicated markers are shown. No signal is observed for JAM-B and decreased signal for CD31 is found compared with wild type sections shown in panel B. The graph in the left panel show a quantification of the CD31 staining observed on 8 femoral sections of control littermate (white bar) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar).

To further understand the function of JAM-B in BM microenvironment, jam-b deficient mice were generated (supplemental Figure 5). Mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio and did not present any gross morphologic or obvious vascular or immune defects. No signal for JAM-B was detected in jam-b deficient mice by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry using JAM-B specific antibody (Figure 3D-F). Further analysis revealed a 2-fold decrease in the frequency of ECs, OBs, and MSC in bones from jam-b−/− mice compared with control animals (Figure 3A-E, supplemental Figure 6). This was confirmed by immunohistochemistry on BM sections in which a 2-fold decrease in CD31 staining was observed (Figure 3F), suggesting that JAM-B contributes to the development or maintenance of the BM stromal microenvironment.

Nonredundant function for JAM-B in the homeostatic maintenance of HSCs

Because HSC niches are known to regulate HSC differentiation and quiescence, hematopoietic differentiation was therefore examined in jam-b−/− mice. For animals of the same sex and weight, an increase in total BM cellularity as well as increased numbers and frequency of LinNeg progenitors were observed in jam-b−/− mice (black bars) compared with control (white bars; Figure 4A), whereas the frequency of mature BM cells was not affected (supplemental Figure 7A). Increased numbers of CMP and GMP cells were also found in jam-b−/− animals (Figure 4B), which may account for the increased BM cellularity and increased number of BM cells able to form CFU-C in jam-b−/− mice (Figure 4C). Moreover, LSK cell frequency was decreased in jam-b−/− mice compared with controls, although their absolute number remained constant (Figure 4B). This prompted us to explore in further details the LT-HSC compartment defined as LSK CD34Neg cells. We found a similar decreased frequency in LT-HSCs, where again the absolute number of these cells remained unchanged (Figure 4D), suggesting that imbalanced proportions of LSK subsets in jam-b−/− mice were compensated by homeostatic regulatory mechanisms such as modification of cell cycle entry. The cell cycle of LSK and HSC compartments was thus examined in control and jam-b−/− mice. In control mice, ∼ 60% and 80% of LSK and HSC-MPP1 cells were quiescent (G0 Phase, Ki-67Neg DapiNeg), whereas in jam-b−/− mice lower proportions (40% and 65%, respectively) cells were in G0 phase (Figure 4E). Accordingly, the percentages of G1 and S/G2/M cells were slightly increased in jam-b−/− mice compared with controls, suggesting that JAM-B slows progenitor cell cycle entry through a non–cell-autonomous mechanism. To understand how JAM-B in the BM microenvironment regulates HSC homeostasis, we examined SDF-1α and SCF production in the BM of jam-b−/− mice. We found no difference in SCF production in jam-b−/− mice compared with control (supplemental Figure 7B), whereas a 50% increase in SDF-1α levels was observed (Figure 4F). Because SDF-1α is known to induce its own major receptor (CXCR4) down-regulation,36 we measured CXCR4 expression on progenitor cells from jam-b−/− mice and found that it was down-regulated at the surface of LSK and HSCs from jam-b−/− mice compared with control (Figure 4G).

BM progenitor phenotype and cell cycle status in jam-b deficient mice. (A) The cellularity, number, and frequency of LinNeg progenitor cells in the bone marrow of jam-b deficient (black bar) or control mice (white bar) are shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. (B) Numbers and frequencies of LSK, CMP, and GMP cells in jam-b deficient (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar) are shown. (C) Colony-forming assays with jam-b deficient (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar). Results are expressed as number of CFU-C per 1000 cells. (D) Left panels: Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the gating strategy used to define LT-HSC. Right panels: Percentage of LT-HSC within the LinNeg population and absolute numbers of LT-HSC are shown. The decreased frequency of LT-HSC observed in jam-b−/− mice does not translate in changes in absolute numbers. (E) Representative dot-plots showing ki-67/DAPI staining gated on LSK cells (top panels) or on HSC-MPP (bottom panels) are shown. The graphs show the frequencies of LSK or HSC-MPP1 cells in Phase G0 (Ki-67Neg DAPINeg), G1 (Ki-67Pos DAPINeg), and S/G2/M (Ki-67Pos DAPIPos) in jam-b−/− mice (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar). Decreased frequencies of progenitor cells in G0 Phase are observed in jam-b−/− mice. (F) The levels of bone marrow SDF-1α contents in jam-b−/− (black bar) or control mice (white bar) assessed by ELISA are shown. Results are expressed as SDF-1α concentration and correspond to the SDF-1α quantity found in 1 leg. (G) Representative histogram profiles showing CXCR4 expression on the indicated hematopoietic subset in control (gray line) and jam-b deficient mice (filled profile). Graphs in the left panels show the percentages and the MFI of CXCR4 expression on the indicated subset in control (white bar) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar). Results are representative of at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

BM progenitor phenotype and cell cycle status in jam-b deficient mice. (A) The cellularity, number, and frequency of LinNeg progenitor cells in the bone marrow of jam-b deficient (black bar) or control mice (white bar) are shown. Results are expressed as mean ± SD. (B) Numbers and frequencies of LSK, CMP, and GMP cells in jam-b deficient (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar) are shown. (C) Colony-forming assays with jam-b deficient (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar). Results are expressed as number of CFU-C per 1000 cells. (D) Left panels: Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the gating strategy used to define LT-HSC. Right panels: Percentage of LT-HSC within the LinNeg population and absolute numbers of LT-HSC are shown. The decreased frequency of LT-HSC observed in jam-b−/− mice does not translate in changes in absolute numbers. (E) Representative dot-plots showing ki-67/DAPI staining gated on LSK cells (top panels) or on HSC-MPP (bottom panels) are shown. The graphs show the frequencies of LSK or HSC-MPP1 cells in Phase G0 (Ki-67Neg DAPINeg), G1 (Ki-67Pos DAPINeg), and S/G2/M (Ki-67Pos DAPIPos) in jam-b−/− mice (black bar) compared with control mice (white bar). Decreased frequencies of progenitor cells in G0 Phase are observed in jam-b−/− mice. (F) The levels of bone marrow SDF-1α contents in jam-b−/− (black bar) or control mice (white bar) assessed by ELISA are shown. Results are expressed as SDF-1α concentration and correspond to the SDF-1α quantity found in 1 leg. (G) Representative histogram profiles showing CXCR4 expression on the indicated hematopoietic subset in control (gray line) and jam-b deficient mice (filled profile). Graphs in the left panels show the percentages and the MFI of CXCR4 expression on the indicated subset in control (white bar) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar). Results are representative of at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

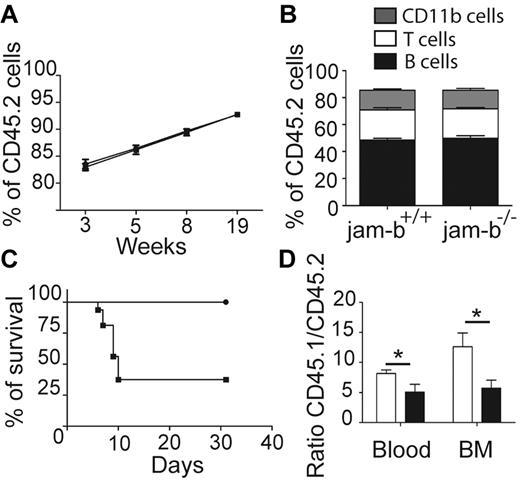

JAM-B expression is required for HSC engraftment and survival after myelo-ablation

To confirm that JAM-B regulates hematopoietic development exclusively through its expression on stromal cells, we tested whether hematopoietic progenitors from jam-b−/− mice would be able to reconstitute lethally irradiated control recipients. To this end, BM cells from jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ CD45.2 mice were grafted into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipient mice. The percentage of chimerism was monitored in the blood for several weeks after transplantation and no difference in chimerism frequency (percentage of CD45.2+ cells) was observed between chimeric mice that had received jam-b−/− versus control BM cells (Figure 5A). Moreover, no obvious difference was observed in the frequency of T (CD3+), B (CD19+), and myeloid (CD11b+) cells between jam-b−/− and jam-b+/+ chimeric mice 19 weeks after graft (Figure 5B). In contrast, when jam-b−/− mice were used as recipient mice, a strong defect was observed. More than 60% of CD45.2+jam-b−/− mice grafted with control CD45.1+ LSK cells did not survive lethal irradiation, whereas CD45.2+ control recipients did (Figure 5C). The surviving CD45.2+jam-b−/− mice presented a decrease in BM engraftment reflected by a decreased chimerism as assessed by the donor-recipient ratio (Figure 5D). Indeed, 4 weeks after LSK cell graft, the CD45.1/CD45.2 ratio was reduced by one-half when recipient mice were jam-b−/− mice (Figure 5D), showing that the BM microenvironment of jam-b−/− is not fully competent to support LSK cell engraftment.

JAM-B expression on stromal cells is required for BM engraftment. (A) The graph shows the percentage of chimerism at different time after graft of jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ CD45.2 BM cells into lethally irradiated recipient CD45.1 mice. jam-b+/+ BM cells as well as jam-b−/− BM cells are able to reconstitute recipient mice. (B) Graph showing the proportion of T (CD3+), B (CD19+) and myeloid (CD11b+) cells in the blood of recipient mice 19 weeks after engraftment with BM cells from the indicated donor. (C) Percentage of survival of jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ mice lethally irradiated and grafted with CD45.1 LSK cells. Most of jam-b−/− mice die after irradiation (square) whereas all control mice survive (circle). (D) The graph shows the percentage of chimerism 4 weeks after graft of CD45.1 LSK cells into control (white bars) or jam-b deficient recipient mice (black bar). Results obtained in the BM and in the blood are shown. Results are representative of at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05).

JAM-B expression on stromal cells is required for BM engraftment. (A) The graph shows the percentage of chimerism at different time after graft of jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ CD45.2 BM cells into lethally irradiated recipient CD45.1 mice. jam-b+/+ BM cells as well as jam-b−/− BM cells are able to reconstitute recipient mice. (B) Graph showing the proportion of T (CD3+), B (CD19+) and myeloid (CD11b+) cells in the blood of recipient mice 19 weeks after engraftment with BM cells from the indicated donor. (C) Percentage of survival of jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ mice lethally irradiated and grafted with CD45.1 LSK cells. Most of jam-b−/− mice die after irradiation (square) whereas all control mice survive (circle). (D) The graph shows the percentage of chimerism 4 weeks after graft of CD45.1 LSK cells into control (white bars) or jam-b deficient recipient mice (black bar). Results obtained in the BM and in the blood are shown. Results are representative of at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05).

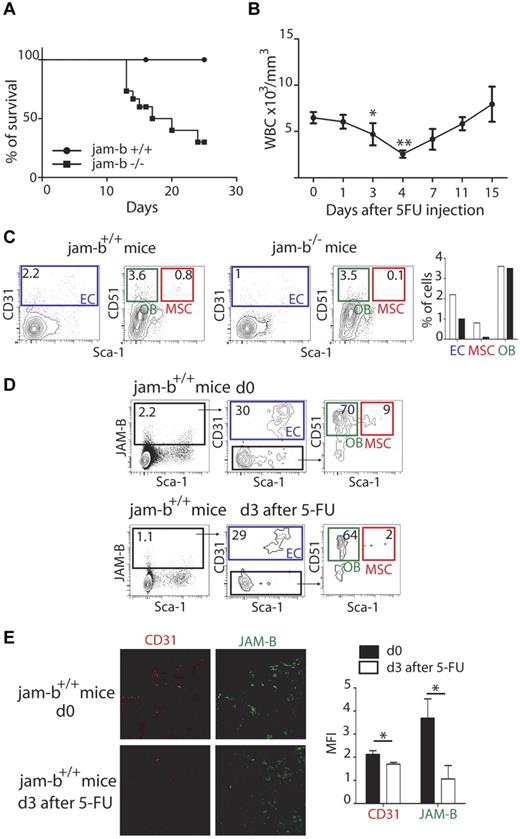

To further confirm that JAM-B supported the maintenance of the HSC pool, exhaustion assays were performed. To this end, 5-FU was administered once a week by intraperitoneal injection to control or jam-b−/− mice and mouse survival was followed. The median survival of jam-b−/− mice was 18.5 days, whereas all control mice survived beyond 25 days (Figure 6A). This defect was from the lack of JAM-B expression on stromal cells because identical experiments performed on chimeric mice reconstituted with either jam-b−/− or jam-b+/+ BM cells also survived beyond 25 days (not shown). To better understand the essential function of JAM-B in maintaining a competent BM microenvironment during myelo-ablation, we compared the composition of the bone marrow stroma on the day preceding the drop in circulating leukocytes normally observed 4 days after 5-FU injection37 (Figure 6B). We found that the MSC and endothelial compartments were more drastically compromised in jam-b−/− mice compared with control animals 3 days after 5-FU injection (Figure 6C). At this time, expression of JAM-B was strongly decreased in control animals with a specific decrease in the proportion of MSCs expressing JAM-B and an overall decrease in the quantity of CD31 expressing endothelial cells (Figure 6D-E). The complete recovery of JAM-B expression on stromal cells was achieved 18 days after 5-FU injection when white blood cell count returned to steady-state levels (supplemental Figure 8), suggesting that JAM-B is an active player in the dynamic changes occurring in the BM microenvironment during myelo-ablation recovery.

Dynamic changes in bone marrow JAM-B expressing stromal cells after 5-FU treatment. (A) The survival curves of jam-b deficient (square) and wild-type control mice (circle) that received 5FU (120 mg/kg) once a week are shown. The survival median for jam-b deficient mice is 18.5 days whereas all control mice were still alive 25 days after initiation of 5FU treatment Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments, n = 6. (B) The graph represents the leukocyte count in the blood of control mice after a single injection of 5-FU. There is a strong decrease of circulating leukocytes between day 3 and 4 after 5-FU injection. (C) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the bone marrow stromal composition of control and jam-b deficient mice 3 days after a single injection of 5-FU. The percentages of ECs, OBs, and MSCs are shown. (D) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the different stromal subsets expressing JAM-B before or 3 days after 5-FU treatment of wild-type mice. A 2-fold decrease in the proportion of stromal cells expressing JAM-B is observed on 5-FU treatment (1.1% vs 2.2%) with a specific decrease in the proportion of MSCs (2% vs 9%). Bones of 6 mice of each group were pooled to obtain enough cells. (E) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections obtained from control or 5-FU treated mice and stained with the indicated markers. Both JAM-B and CD31 signals are reduced after 5-FU treatment. The graph in the left panel show a quantification of CD31 and JAM-B staining observed on 8 femoral sections of control (black bars) and 5-FU treated mice (mice bar). Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with at least 5 mice per group.

Dynamic changes in bone marrow JAM-B expressing stromal cells after 5-FU treatment. (A) The survival curves of jam-b deficient (square) and wild-type control mice (circle) that received 5FU (120 mg/kg) once a week are shown. The survival median for jam-b deficient mice is 18.5 days whereas all control mice were still alive 25 days after initiation of 5FU treatment Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments, n = 6. (B) The graph represents the leukocyte count in the blood of control mice after a single injection of 5-FU. There is a strong decrease of circulating leukocytes between day 3 and 4 after 5-FU injection. (C) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the bone marrow stromal composition of control and jam-b deficient mice 3 days after a single injection of 5-FU. The percentages of ECs, OBs, and MSCs are shown. (D) Representative flow cytometry profiles showing the different stromal subsets expressing JAM-B before or 3 days after 5-FU treatment of wild-type mice. A 2-fold decrease in the proportion of stromal cells expressing JAM-B is observed on 5-FU treatment (1.1% vs 2.2%) with a specific decrease in the proportion of MSCs (2% vs 9%). Bones of 6 mice of each group were pooled to obtain enough cells. (E) Confocal images of 20-μm-thick femoral sections obtained from control or 5-FU treated mice and stained with the indicated markers. Both JAM-B and CD31 signals are reduced after 5-FU treatment. The graph in the left panel show a quantification of CD31 and JAM-B staining observed on 8 femoral sections of control (black bars) and 5-FU treated mice (mice bar). Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with at least 5 mice per group.

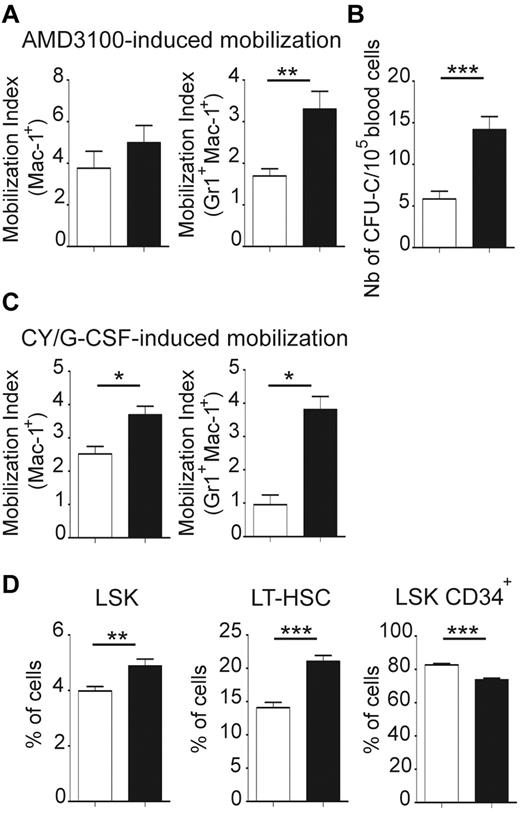

Jam-B deficient mice exhibit exacerbated responses to mobilizing agents

To test if the BM microenvironment of jam-b deficient mice provides the suitable retention signals to HSCs, we compared HSC mobilization efficiency in control and jam-b−/− mice. Results were expressed by a mobilization index which was defined as the frequency of circulating cells after mobilization divided by the frequency 2 weeks before mobilization to take into account individual variations at the steady state (Figure 7A-C). No difference in the mobilization index of Mac1Pos cells was found between control and jam-b−/− mice following AMD 3100 mobilization. However, there were twice as many granulocytes (Mac1PosGr1PosF4/80Neg) mobilized in jam-b−/− mice compared with control mice (Figure 7A). Moreover, as shown by CFU-C assays, there were 3 times as many progenitors circulating in the blood of jam-b−/− mice after AMD3100-induced mobilization compared with control animals (Figure 7B). When using the Cy/G-CSF protocol, we found a 2-fold increase in the mobilization index of Mac1+ cells and a 4-fold increase in the granulocyte mobilization index in jam-b−/− mice compared with control animals (Figure 7C). This was reflected by a greater frequency of LSK cells in the BM of jam-b−/− mice, mostly because of a greater expansion of the LT-HSC compartment (Figure 7D). This shows that HSC retention into BM microenvironment is altered in jam-b−/− mice and suggests that JAM-B is an active player in the dynamic maintenance of the LT-HSC pool by stromal cells.

Exacerbated BM mobilization in jam-b deficient mice. (A) The graphs show the mobilization indexes for the indicated subsets after AMD 3100 induced-mobilization in jam-b deficient mice (black bars) compared with control animals (white bars). (B) The number of circulating progenitor cells mobilized in the blood of jam-b deficient (black bar) and control mice (white bar) 3 hours after AMD3100 treatment is shown. (C) The mobilization indexes for the indicated subsets after Cy/G-CSF induced-mobilization in control (white bars) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar) are shown. (D) The frequencies of LSK, LT-HSC (LSK CD34Neg), and LSK CD34Pos cells after AMD 3100 induced-mobilization in the bone marrow of control (white bars) and jam-b deficient mice (black bars) are shown. Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Exacerbated BM mobilization in jam-b deficient mice. (A) The graphs show the mobilization indexes for the indicated subsets after AMD 3100 induced-mobilization in jam-b deficient mice (black bars) compared with control animals (white bars). (B) The number of circulating progenitor cells mobilized in the blood of jam-b deficient (black bar) and control mice (white bar) 3 hours after AMD3100 treatment is shown. (C) The mobilization indexes for the indicated subsets after Cy/G-CSF induced-mobilization in control (white bars) and jam-b deficient mice (black bar) are shown. (D) The frequencies of LSK, LT-HSC (LSK CD34Neg), and LSK CD34Pos cells after AMD 3100 induced-mobilization in the bone marrow of control (white bars) and jam-b deficient mice (black bars) are shown. Results are representative of at least 3 independent experiments with at least 5 mice per group (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that junctional adhesion molecule-B expressed by stromal cells plays a role in hematopoiesis through heterotypic interaction with JAM-C-expressing hematopoietic cells. JAM-B binding to LSK cells discriminates between LT-HSCs and more differentiated progenitors. This is consistent with the deregulated homeostasis of BM progenitor cells observed in jam-b−/− mice. Although previous studies have correlated the levels of JAM-C expression with LSK differentiation and reported hematopoietic defects in jam-c deficient mice,11,13 the function of JAM-C and the nature of the ligand used by JAM-C in the surrounding BM microenvironment were not identified. The protein JAM-B is the highest affinity ligand for JAM-C, and JAM-B interaction with the VLA-4 is facilitated by co-expression of JAM-C.6,7 Here, we show that JAM-B interaction with HSCs is dependent on JAM-C expression and not affected by VLA-4, although we cannot exclude a role for additional mechanisms because LSK cells adhere to JAM-B only after PMA activation. This third partner hypothesis is consistent with the fact that binding of JAM-B to LSK cells is not systematically associated with JAM-C expression (Figure 1B-C). Indeed, a subset of MPP2 cells that does not bind sol-JAM-B (30%) was identified, whereas uniform expression of JAM-C was found on MPP2. This indicates that JAM-B binding to LSK cells is a better marker of long-term reconstitution potential than JAM-C expression and that JAM-B/JAM-C interaction may be regulated by additional mechanisms. Whether such regulatory mechanisms may apply to other recently described markers of LT-HSCs such as JAM-A or ESAM remains to be tested.15,16,38

Although jam-b mRNA has been detected in HSCs and LSK cells by gene expression profiling studies,11,14 we were unable to detect JAM-B surface expression on progenitor cells. The analysis of JAM-B and JAM-C expression patterns is still hampered by the use of an old and confusing nomenclature despite the publication of a proposed consensus.39 For example, some studies have reported JAM-B expression on LSK cells using antibodies generated in our laboratory that are directed against mouse JAM-C.11,40 We find JAM-B expression predominantly associated with the vascular and perivascular compartments of the BM, consistent with previous reports demonstrating JAM-B expression on endothelial and stromal cells in the niche.2,41,42 As such, the current view is that JAM-C expressed by HSCs interacts with JAM-B expressed by BM stromal cells.

A second piece of evidence supporting the hypothesis that JAM-B/JAM-C interaction is involved in HSC retention in niches is the cell cycle status of LT-HSCs in jam-b deficient mice. Cycling of HSCs has been correlated with their exit from the niches.43 In wild-type mice, it is estimated that around 5% of HSCs are cycling, in contrast to cxcr4 deficient mice in which increased frequency of cycling HSCs leads to exhaustion of HSCs.44 Here, we show that jam-b deficient mice present a phenotype similar to cxcr4 deficient mice with an exacerbated response to mobilizing agents. This is consistent with a loosening of the interaction between HSC and stromal cells in jam-b deficient mice. Indeed, mobilization induced by cyclophosphamide and G-CSF requires progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation, wheras AMD3100 induces BM cells mobilization without the need of homeostatic response.25,26 In both experimental models, JAM-B appears to be a brake for egress during mobilization. This result fits well with a model in which adhesion molecules are involved in HSC retention in the BM stromal niches.21,43

We also report that the plasticity of BM stromal compartment can be followed using JAM-B as a marker of stromal subsets, and that the composition of the BM stroma is altered in jam-b deficient mice. Indeed, a 2-fold decrease in the proportion of endothelial cells, osteoblasts, and mesenchymal stem cells is observed in jam-b deficient mice compared with control animals (supplemental Figure 6). Because these 3 cell types contribute to HSC niches,45 the net result may be a reduced number of available niches for HSCs in jam-b deficient mice.46,47 Reduced niche availability could in turn disturb the balance of HSCs in the quiescent state and affect the levels of HSC maintenance factors such as SDF-1α. Although one would expect that the increase in SDF-1α content would reinforce HSC retention in the BM, we observed an exacerbated mobilization in jam-b deficient mice induced by cyclophosphamide/G-CSF or AMD3100. This apparent discrepancy could be explained by the fact that G-CSF induces mobilization through protease degradation of SDF-1α48 and that the drop in SDF-1α BM content is exacerbated in jam-b deficient mice. Similarly, the AMD3100 mobilization, which relies on antagonization of CXCR4,25 will be more efficient in jam-b deficient mice which present reduced levels of CXCR4 expression. Current studies aim at understanding the mechanisms by which SDF-1α is increased in the BM of jam-b deficient mice. Whether this is because of changes in stromal cell composition or exacerbated JAM-C signal transduction which we have recently shown to be mandatory for SDF-1α secretion remains to be addressed.10 Finally, we demonstrate that a single 5-FU injection results in a drastic reduction of JAM-B expressing BM stromal cells with a specific loss of JAM-B expressing MSC. We do not know whether these MSC are identical to CAR cells, NestinPos, or PDGFR-αPosSca-1Pos MSCs that are associated with sinusoidal endothelium,49-51 but the colocalization of the JAM-B staining with the mesenchymal marker α-SMA in perivascular regions is compatible with this hypothesis.

In summary, we have shown that JAM-B expressed by bone marrow stromal cells interacts with JAM-C expressed on HSCs and is an active player in the maintenance of the LT-HSC pool. Future studies may address whether anti–JAM-B therapy is a promising strategy to target the bone marrow microenvironment in leukemia.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. R. Galindo for assistance in flow cytometry sorting and D. Isnardon for confocal imaging. They thank L. Chasson from the Histology Platform at the CIML for cryosectioning, and A. Zarubica, D. Birnbaum, J. P. Borg, E. Soucie, P. Dubreuil, C. Mawas, and S. Sarrazin for critical reading of the paper and valuable advice.

This work was supported by Inserm Avenir program, Inca, Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC #4981 to M.A.-L.), Feder and Swiss National Science Foundation (#31-112551 to M.A.-L.). M.-L.A. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) and the Lilly Institute, and V.F. was supported by a doctoral fellowship from Inserm/Region and ARC.

Authorship

Contribution: M.-L.A. and M.A.-L. designed the experiments; M.-L.A., C.S., C.C., S.J.C.M., and M.A.-L. wrote the paper; M.-L.A. performed all experiments; V.F., F.B., E.O., L.C., S.J.C.M. performed some experiments; and S.A., R.H.A., and M.A.-L. generated deficient mice.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Correspondence: Michel Aurrand-Lions or Marie-Laure Arcangeli, Inserm, Centre de Researche en Cancérologie de Marseille, 27 bd Lei Roure, BP30059 13273 Marseille Cedex 09, France; e-mail: michel.aurrand-lions@inserm.fr or marie-laure.arcangeli@inserm.fr.