Abstract

Abstract 1000

Natural killer (NK) cells exhibit in vitro cytotoxicity against many tumor cell types and have an important role in controlling tumor growth, as depletion of NK cells from tumor-bearing mice hastens tumor growth and impairs survival. These data, in combination with results from clinical trials of haploidentical killer immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR)-ligand mismatched bone marrow transplantation, led to interest in the use of adoptive NK immunotherapy for the treatment of malignancy. Recent clinical results have shown that allogeneic NK cells can be safely administered after chemotherapy and/or irradiation but have also demonstrated limited persistence of the infused NK cells without clear evidence of efficacy. We traced the fate of adoptively infused NK cells in order to delineate the barriers to successful NK immunotherapy using several NK-sensitive murine tumor models.

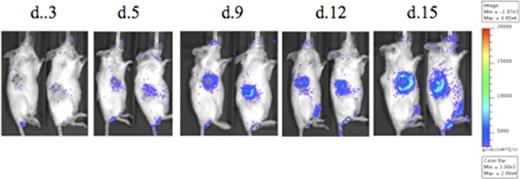

Adoptively transferred luciferase-transgenic NK cells accumulate within the tumor over time

Adoptively transferred luciferase-transgenic NK cells accumulate within the tumor over time

Eomesodermin and T-bet are transcription factors with important roles in effector functions of CD8+ T cells and NK cells. In T cells T-bet downregulation has been shown to correlate with exhaustion (Kao et al, Nat Imm 2011). Flow cytometry of reisolated NK cells revealed downregulation of Eomesodermin (naive splenic control, d+1 reisolated and d+10 reisolated cells showing 85%, 96%, and 29% expression, respectively) and T-bet (naive splenic control, d+1 reisolated and d+10 reisolated cells showing 82%, 99%, and 59% expression, respectively), correlating with loss of IFNγ production.

The phenotype described herein was most dramatic within the tumor and within mice carrying high tumor burdens, but was also present in NK cells reisolated from non-tumor bearing animals that received NK cells, suggesting that homeostatic proliferation after transfer of mature NK cells could also contribute to exhaustion. CFSElo proliferated NK cells showed the most dramatic loss of effector function (chromium release = 42% in unproliferated vs 18% in proliferated cells, p = 0.03) and transcription factor expression (Eomesodermin positive 83% in unproliferated cells vs 18% in proliferated cells, p = 0.002).

Collectively, our results suggest that the success of NK cell immunotherapy is limited by an acquired dysfunction that occurs within days after homeostatic proliferation and target encounter and that may be related to the downregulation of transcription factors required for NK effector function. These findings illuminate a previously unappreciated phenomenon and explain why short-term in vitro killing assays have limited utility in predicting the in vivo behaviour of transferred NK cells. Hence, these findings suggest that transferred NK cells become dysfunctional in vivo and that novel approaches may be required in order to circumvent the described dysfunction phenotype.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.