Abstract

Abstract 3154

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a common hematologic problem worldwide, potentially leading to cognitive delays, fatigue, seizures, and, when severe, high output heart failure. While IDA frequently is encountered in both the primary care setting and specialty clinics, its management is not evidence based. As a result, the diagnosis and treatment of IDA is often suboptimal. To help inform future clinical trials, we retrospectively characterized the clinical course of IDA in young patients (pts) referred to our center.

Using our comprehensive hematology database, the records of children ≤ 18 years (yrs) of age with IDA seen in our outpatient clinic between January 1, 2006 and June 30, 2010 were identified and carefully reviewed.

Of 217 IDA pts in the database, 215 had evaluable records, 20 of whom were determined to have an alternative diagnosis. Of 195 evaluable pts, 64% were ≤4 yrs old at their first clinic visit and 31% were age 11–18 yrs. Pts ≤ age 4 yrs were 63% male and 60% Hispanic, whereas those age 11–18 yrs were 83% female and 37% Hispanic, 35% African-American, and 15% Caucasian.

Causes of IDA in 128 pts ≤ 4 yrs were excessive consumption of cow milk (68%), breast feeding without iron supplementation (13%), overall iron-poor diet beyond 12 months (16%), prematurity (5%), and suspected malabsorption (6%). Causes of IDA in 60 pts aged 11–18 yrs were menorrhagia (43%), other blood loss (20%), iron-poor diet (22%), and poor iron absorption (7%). Some pts in both age groups had multiple causes of IDA, and in 17 the cause of the anemia was not clear.

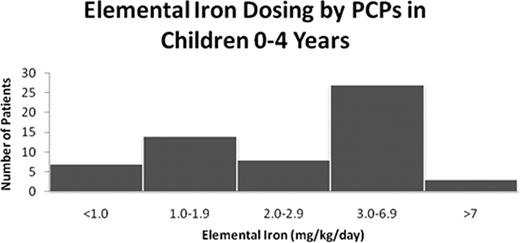

129 pts (66%) were referred to us directly by their primary care physician (PCP), and 49 (25%) by the emergency department (ED), 37 of whom had been sent there by their PCP for evaluation of anemia. Prior to their first visit to our center, 115 pts (59%) had received at least one trial of iron therapy, 62 with ferrous sulfate, 27 with carbonyl iron, 5 with iron polysaccharide, and 15 with an iron-containing multivitamin. For the pts ≤ 4 yrs of age where the precise dose of elemental iron prescribed by the PCP was known (n=59), greater than half of the pts were prescribed doses of iron outside of the accepted therapeutic range (3–6 mg/kg/day) (see figure). The pts' mean Hb concentration before referral to our clinic (last recorded Hb measured either by the PCP or the ED) was 7.8 g/dl (n=170).

Following evaluation in our hematology clinic, 86% of patients were treated with ferrous sulfate. However, 17% of such pts ≤ 4 yrs of age still received iron doses outside of the accepted therapeutic range. At the time of their first and last visits to the hematology clinic the mean Hb values were 9.0 g/dl and 11.3 g/dl respectively. One third of pts had documented poor adherence with iron therapy, due to poor tolerability (19%), gastrointestinal upset (11%), misunderstanding of prescribed dose (14%), and use of a lower dose than prescribed due to parental discretion (41%). 40% of pts were lost to follow up.

Among pts referred for IDA to our academic specialty clinic, Hispanic male toddlers and Hispanic or African-American female adolescents were disproportionately represented. Most toddlers had nutritional IDA while most adolescents had menorrhagia. Pts often received sub-therapeutic doses of iron before referral. After hematology clinic evaluation, most children demonstrated improvement of IDA; however, inappropriate dosing and non-adherence with oral iron therapy were high, and many pts were lost to follow up.

Insufficient screening and prevention of IDA remains problematic. Additionally, when IDA is suspected it is often inadequately treated or inappropriately referred to the ED or the hematology clinic, where treatment is associated with poor adherence and high attrition rates. Future research must focus on all of these deficiencies to prevent the many immediate and long-term sequelae of IDA.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.