To the editor:

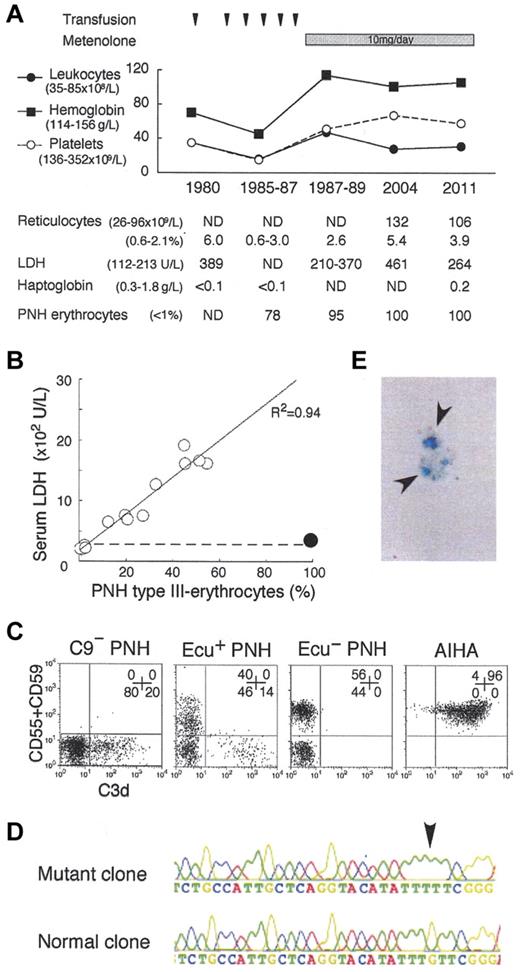

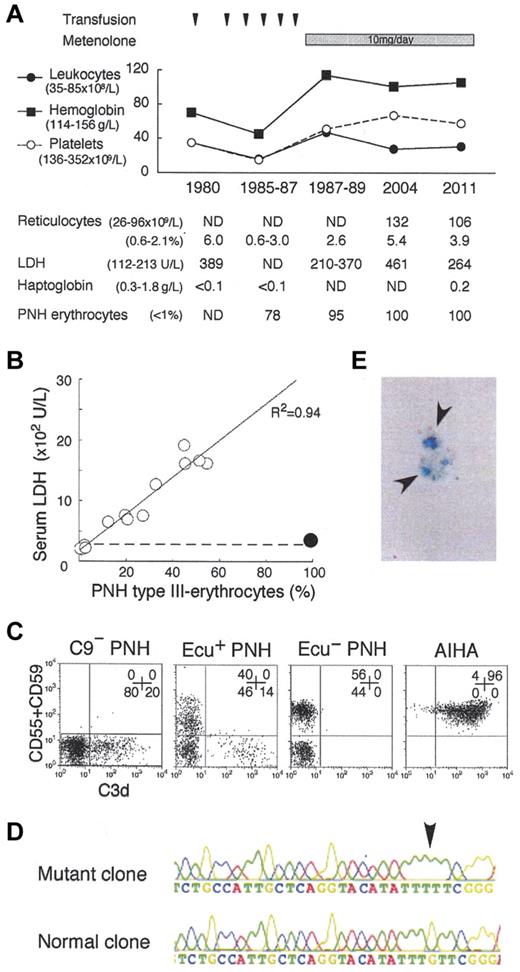

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) clone bears a PIGA mutation and fails to express glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked membrane proteins such as complement-regulatory CD55 and CD59, leading to complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis and thrombosis. The advent of eculizumab, an inhibitor of terminal complement C5, provides good quality of life (QOL) by preventing hemolysis and thrombosis,1,2 and may improve prognosis of PNH patients.3 However, the safety of its long-term use for more than 10 years1,2 and the pathogenesis of eculizumab-associated extravascular hemolysis have not been established.4 For the hemolysis, steroid, splenectomy,5 and C3-targeted therapy6 have been proposed, despite their individual risks.7 In 1980, we found a PNH patient with a coexisting congenital deficiency of C9, still the only case globally.8 Presently, the patient is 78 years old and has kept a high QOL (no experience of massive hemolysis, thrombotic events, critical infection, or malignant diseases) for more than 31 years after the PNH diagnosis. Of note, the patient manifests very low levels of PNH hemolysis (Figure 1A-B) and marrow failure (Figure 1A). The high QOL may reflect that the C9-deficiency prevents membrane attack complex (C5b-9) formation but allows immune reactions by generation of C5a and C5b-8.7 Currently, virtually all erythrocytes (and granulocytes) of the patient showed the PNH phenotype (Figure 1A-C). Whole blood cells had the same PIGA mutation in 1998 and 2011 (Figure 1D), indicating that the cells are of a single PNH clone. Marrow cells showed a normal karyotype. These findings support the concept that clonal hematopoiesis in PNH is a benign process. The clinical features suggest the safety and efficacy of long-term inhibition of terminal complement including C9 for even elderly PNH patients. Thus, we propose that C9 targeting is another option for PNH therapy.2

Analysis of the C9-deficient patient with PNH. (A) Clinical profile of the C9-deficient patient with PNH. ND indicates not determined; and PNH erythrocytes, negative for both CD55 and CD59. (B) Correlation between LDH levels and PNH type III erythrocytes (%). ○, 14 patients with PNH; •, C9-deficient patient with PNH; dashed line, upper limit of normal LDH range. (C) C3d expression on erythrocytes of PNH patients with C9 deficiency (C9− PNH), with eculizumab (Ecu+ PNH), without eculizumab (Ecu− PNH), and of a patient with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). Numbers indicate the population (%) of cells in each quadrant. (D) Arrow indicates a PIGA mutation, deletion of G (352), in the granulocyte genome exon 2 of C9− PNH. (E) Arrows indicate urine hemosiderin stained with Prussian blue of C9− PNH.

Analysis of the C9-deficient patient with PNH. (A) Clinical profile of the C9-deficient patient with PNH. ND indicates not determined; and PNH erythrocytes, negative for both CD55 and CD59. (B) Correlation between LDH levels and PNH type III erythrocytes (%). ○, 14 patients with PNH; •, C9-deficient patient with PNH; dashed line, upper limit of normal LDH range. (C) C3d expression on erythrocytes of PNH patients with C9 deficiency (C9− PNH), with eculizumab (Ecu+ PNH), without eculizumab (Ecu− PNH), and of a patient with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). Numbers indicate the population (%) of cells in each quadrant. (D) Arrow indicates a PIGA mutation, deletion of G (352), in the granulocyte genome exon 2 of C9− PNH. (E) Arrows indicate urine hemosiderin stained with Prussian blue of C9− PNH.

Hemosiderinuria (Figure 1E) is an indicator of intravascular hemolysis, probably induced by C5b-8 in the C9-deficient patient.7 Surprisingly, the patient had C3d-bound erythrocytes (Figure 1C) that often appear in PNH patients on eculizumab4,5 and are susceptible to extravascular hemolysis.7 Thus, the patient manifests extremely low levels of both intra- and extravascular hemolysis. It is interesting to verify whether ordinary PNH patients harbor dormant extravascular hemolysis. Judging from the fluorescence intensity of C3d-positive erythrocytes, the amount of C3d on the PNH erythrocytes of our patient appears less than that of some PNH patients on eculizumab (Figure 1C; current report4 ). In contrast, C3d+ erythrocytes were undetectable in PNH patients before eculizumab treatment (Figure 1C).4 The amount of C3d on erythrocytes may inversely correlate with the intensity of intravascular hemolysis. It then led us to speculate that intravascular hemolysis is too rapid to allow extravascular clearance of C3d-bound PNH erythrocytes in vivo. It is also theoretically possible that eculizumab-associated extravascular hemolysis is controllable by decreasing the dose of eculizumab. The C3d deposition could also be affected by the altered expression of erythrocyte glycolipids.9 In general, infection amplifies both intravascular hemolysis of PNH10 and extravascular hemolysis of hereditary spherocytosis. Eculizumab may not completely eliminate the infection-associated precipitation of hemolysis in PNH patients having both types of hemolysis.

The findings in our exceptional PNH patient surely promote unveiling of complex pathophysiology and contribute to the establishment of a better terminal complement-targeted therapy in PNH.

Authorship

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Kentaro Horikawa and Tatsuya Kawaguchi of Kumamoto University, Takahiko Horiuchi of Kyushu University, and Michiyo Hatanaka of Kobe Tokiwa University for critical discussion, and Naoto Minoura, Kenichi Nakatsuka, and Kazuki Fujii of Wakayama Medical University for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, the Ministry of Labor and Welfare of Japan, and the Takeda Science Foundation.

Contribution: N.H. designed and performed research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; Y.M. and T.K. performed molecular analyses; M.N., S.N., Y.Y., and T.S. analyzed the clinical data; and H.N. supervised the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.Y., T.K., and H.N. receive honoraria from Alexion Phamaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hideki Nakakuma, Department of Hematology/Oncology, Wakayama Medical University, 811-1 Kimiidera, Wakayama 641-8510, Japan; e-mail: hnakakum@wakayama-med.ac.jp.