To the editor:

Therapeutic targeting of the Bcl-2 family of pro-survival proteins is a promising new anticancer approach that is currently being evaluated in phase 1/2 clinical trials. ABT-263 (Navitoclax), is a well tolerated Bcl-2/Bcl-xL/Bcl-w–inhibitory BH3-mimetic that exhibits efficacy in human hematologic malignancies.1 Thrombocytopenia represents the major dose-limiting side effect of this class of compounds,1 because of their ability to antagonise the pro-survival function of Bcl-xL, leading to Bak/Bax-dependent platelet apoptosis.2 Recent studies in mice have also demonstrated that ABT-263 can induce functional defects in residual circulating platelets, leading to a transient thrombocytopathy that can undermine their hemostatic function (Figure 1A).3 Given that many patients receiving ABT-263 have pre-existing thrombocytopenia from their hematologic malignancies, understanding the impact of these potential new therapies on the hemostatic function of residual circulating platelets is important.

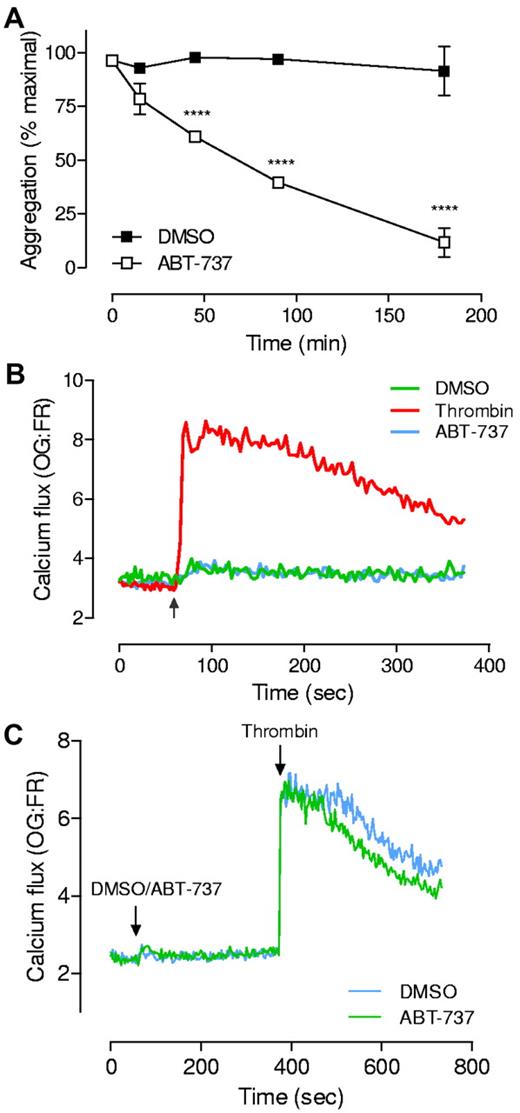

Examination of platelet function and cytosolic calcium flux on addition of Bcl-xL-inhibitory BH3 mimetics. (A) Washed platelets3,5 (3.0 × 108/mL) in Tyrode's buffer were treated with ABT-737 (1μM) for up to 180 minutes. At the indicated times, aggregation in response to thrombin (0.1 U/mL) was monitored at 37°C in a 4-channel automated platelet analyser (AggRAM, Helena Laboratories).3 Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 5; where ***P < .001). (B-C) Washed platelets (3.0 × 108/mL) loaded with Oregon-green BAPTA (OG) and Fura-Red (FR)9 were resuspended in Hepes-buffered saline (HBS) and either treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL), ABT-737 (10μM) or an equivalent volume of DMSO. Calcium flux was monitored continuously, both before and after addition of agonist or drug (indicated by the arrow), for a total of 6-12 minutes, at 535 and 660 nm, using a fluorescence plate reader and Wallac 1420 workstation software (Wallac VICTOR2 1420 multilabel counter, Perkin Elmer). Traces represent data collected from 1 experiment representative of at least 4 independent experiments. Note: for all experiments, similar results were obtained on addition of ABT-263 or ABT-737 (1-10μM). Moreover, similar results were obtained under a variety of different assay conditions (washed platelets resuspended in Tyrode buffer, in the presence or absence of EGTA) or using different calcium indicator dyes (Fluo-3).

Examination of platelet function and cytosolic calcium flux on addition of Bcl-xL-inhibitory BH3 mimetics. (A) Washed platelets3,5 (3.0 × 108/mL) in Tyrode's buffer were treated with ABT-737 (1μM) for up to 180 minutes. At the indicated times, aggregation in response to thrombin (0.1 U/mL) was monitored at 37°C in a 4-channel automated platelet analyser (AggRAM, Helena Laboratories).3 Results represent the mean ± SEM (n = 5; where ***P < .001). (B-C) Washed platelets (3.0 × 108/mL) loaded with Oregon-green BAPTA (OG) and Fura-Red (FR)9 were resuspended in Hepes-buffered saline (HBS) and either treated with thrombin (0.5 U/mL), ABT-737 (10μM) or an equivalent volume of DMSO. Calcium flux was monitored continuously, both before and after addition of agonist or drug (indicated by the arrow), for a total of 6-12 minutes, at 535 and 660 nm, using a fluorescence plate reader and Wallac 1420 workstation software (Wallac VICTOR2 1420 multilabel counter, Perkin Elmer). Traces represent data collected from 1 experiment representative of at least 4 independent experiments. Note: for all experiments, similar results were obtained on addition of ABT-263 or ABT-737 (1-10μM). Moreover, similar results were obtained under a variety of different assay conditions (washed platelets resuspended in Tyrode buffer, in the presence or absence of EGTA) or using different calcium indicator dyes (Fluo-3).

In this context, Vogler and colleagues recently reported that platelet exposure to ABT-263 induces the rapid depletion of intracellular calcium stores, leading to defective platelet functional responses induced by physiologic agonists.4 ABT-263 was demonstrated to mobilize a robust cytosolic calcium response, suggesting that this compound might have platelet activating properties. However, several independent reports have not demonstrated direct platelet activation by ABT-263 (or the related ABT-737).3,5,6 The study by Vogler et al has raised the provocative possibility that the deleterious impact of ABT-263 on platelet function may involve 2 distinct mechanisms, an immediate effect linked to depletion of intracellular calcium stores, and a delayed effect, because of Bak/Bax-mediated apoptosis.

We have monitored calcium flux in platelets exposed to ABT-263 (and ABT-737) under a variety of different assay conditions (refer to figure legend), including those described by Vogler.4 Our studies were unable to demonstrate any significant calcium flux induced by ABT-737 (Figure 1B) or ABT-263 (data not shown), above that observed with vehicle alone (DMSO, Figure 1B). Moreover, we found that brief exposure to ABT-737 had no detrimental effect on platelet responsiveness to subsequent soluble agonist stimulation. Platelets exposed to ABT-737 (or ABT-263) for less than 10 minutes, and subsequently challenged with thrombin (0.5 U/mL), were capable of initiating a calcium flux, indistinguishable from vehicle controls (Figure 1C), indicating that intracellular calcium stores remained intact. These findings do not support the conclusions by Vogler et al that BH3 mimetics can modulate platelet function through depletion of intracellular calcium stores.

Evidence exists to support a role for Bcl-2 proteins in modulating calcium cross-talk between the mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER).7 In this regard, it is notable that HA 14-1, a suggested Bcl-2 inhibitor structurally unrelated to ABT-737 and ABT-263, has been demonstrated to promote apoptosis in tumor cells through dual actions on the mitochondria and ER, initiating ER stress and depleting calcium stores.8 However, this has not been demonstrated with the Bcl-xL–inhibitory mimetics ABT-737 and ABT-263,8 which appear to mediate their cellular effects specifically through the mitochondria without impacting on the ER and intracellular calcium stores.8 Consistent with this, our studies3,5 and those of other independent laboratories6 do not support a role for ABT-737 or ABT-263 in regulating acute changes in platelet cytosolic calcium flux. Rather, the deleterious impact of these agents on platelet function is likely to be primarily related to the induction of mitochondrially-driven apoptosis events, since all ABT-263 and ABT-737 effects on platelets are abolished in the absence of Bak and Bax.5

Authorship

Acknowledgments: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (project grants 516725 and 1023029; fellowship to S.P.J).

Contribution: S.M.S. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and S.P.J. designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Simone M. Schoenwaelder, Australian Centre for Blood Diseases, and the Department of Clinical Hematology, Monash University, 6th level Burnet Building, 89 Commercial Road, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 3004; e-mail: simone.schoenwaelder@monash.edu.