Abstract

ERG and FLI1 are closely related members of the ETS family of transcription factors and have been identified as essential factors for the function and maintenance of normal hematopoietic stem cells. Here genome-wide analysis revealed that both ERG and FLI1 occupy similar genomic regions as AML1-ETO in t(8;21) AMLs and identified ERG/FLI1 as proteins that facilitate binding of oncofusion protein complexes. In addition, we demonstrate that ERG and FLI1 bind the RUNX1 promoter and that shRNA-mediated silencing of ERG leads to reduced expression of RUNX1 and AML1-ETO, consistent with a role of ERG in transcriptional activation of these proteins. Finally, we identify H3 acetylation as the epigenetic mark preferentially associated with ETS factor binding. This intimate connection between ERG/FLI1 binding and H3 acetylation implies that one of the molecular strategies of oncofusion proteins, such as AML1-ETO and PML-RAR-α, involves the targeting of histone deacetylase activities to ERG/FLI1 bound hematopoietic regulatory sites. Together, these results highlight the dual importance of ETS factors in t(8;21) leukemogenesis, both as transcriptional regulators of the oncofusion protein itself as well as proteins that facilitate AML1-ETO binding.

Introduction

E-twenty-six (ETS) specific transcription factors are a family of > 20 helix-loop-helix domain transcription factors that have been implicated in a myriad of cellular processes, including hematopoiesis.1 The hallmark ETS factor protein involved in hematopoietic development is SPI1 (Spleen focus forming virus Proviral Integration site 1; PU.1), which activates gene expression during myeloid and B-lymphoid cell development. Other ETS factors include the 2 closely related transcriptional activator proteins ERG (Ets Related Gene) and FLI1 (Friend Leukemia virus Integration site 1), which both play crucial roles in hematopoietic development2,3 and multiple forms of cancer.4,5

Recently, SPI1 was identified as a binding partner of the PML-RAR-α oncofusion protein complex in an inducible overexpression model.6 The PML-RAR-α oncofusion protein is the result of a translocation t(15;17)(q22;q21) involving the promyelocytic leukemia (PML) gene on chromosome 15 and the retinoic acid receptor-α (RAR-α) on chromosome 17.7,8 Another translocation, t(8;21)(q22;q22), is present in ∼ 10% of all de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cases, and results in the expression of the AML1-ETO (RUNX1-RUNX1T1) oncofusion protein. Expression of the AML1-ETO oncofusion protein in hematopoietic cells results in a stage-specific arrest of maturation and increased cell survival, predisposing cells to develop leukemia.9 At the molecular level RUNX1 (Runt-related transcription factor 1; AML1, CBFA2) represents a DNA-binding transcriptional activator factor required for hematopoiesis,10,11 while ETO (eight-twenty-one; MTG8, RUNX1T1) acts as a corepressor molecule.12 The t(8;21) translocation replaces the transactivation domain of RUNX1/AML1 with the almost complete ETO protein, thereby converting an essential transcriptional activator into a strong repressor.13,14

Here we extend genome-wide AML1-ETO studies15,16 and reveal that a subset of AML1-ETO binding sites are bound by CBF-β (core binding factor-β), whereas nearly all are bound by HEB (HeLa E-box–binding factor), RUNX1/AML1 as well as by the ETS factors ERG and FLI1. Subsequent analysis in t(8;21) cells revealed cell type specific ETS factor binding and preferential AML1-ETO binding to the cell type specific ETS factor binding sites, suggesting that these proteins facilitate oncofusion protein binding. In addition, we uncovered that binding of the ETS factors correlates with the “active” histone acetylation mark. Together, our results suggest that ETS factors demarcate hematopoietic regulatory sites that provide a target for (aberrant) epigenetic regulation by oncofusion proteins.

Methods

ChIP

Chromatin was harvested as described.17 ChIPs were performed using specific antibodies to ETO, HEB, ERG, FLI1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), H3K9K14ac, AML1-ETO, ETO, CBF-β, RNAPII (Diagenode), RUNX1, and FLI1 (Abcam), and H4panAc (Millipore) and analyzed by quantitative PCR or ChIP-seq. Primers for quantitative PCR are described in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Relative occupancy was calculated as fold over background, for which the second exon of the Myoglobin gene or the promoter of the H2B gene was used.

Illumina high throughput sequencing

End repair was performed using the precipitated DNA of ∼ 6 million cells (3 or 4 pooled biologic replicas) using Klenow and T4 PNK. A 3′ protruding A base was generated using Taq polymerase, and adapters were ligated. The DNA was loaded on gel and a band corresponding to ∼ 300 bp (ChIP fragment + adapters) was excised. The DNA was isolated, amplified by PCR, and used for cluster generation on the Illumina 1G genome analyzer. The 32- to 35-bp tags were mapped to the human genome HG18 using the eland program allowing 1 mismatch. For each base pair in the genome, the number of overlapping sequence reads was determined and averaged over a 10-bp window and visualized in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu). A list of the ChIP-seq profiles analyzed in this study can be found in supplemental Methods.

Patients' AML blasts and normal CD34+ hematopoietic cells

t(8;21) AML blasts from peripheral blood or bone marrow from de novo AML patients were studied after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Board of the University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. AML mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and AML CD34+ cells were selected as described.18 Percentages of CD34+ cells in the mononuclear AML cell fraction for patient 186 were 25%, 38% for patient 229, and 32% for patient 12. Normal CD34+ cells were obtained from bone marrow of donors following written informed consent. APL blasts were obtained from a patient with newly diagnosed AML having t(15;17). The sample consisted of > 80% bone marrow invasion and was a typical FAB M3 expressing the Bcr1 PML-RAR-α variant. These studies were approved by the SUN Ethical Committee (7028032003).

Results

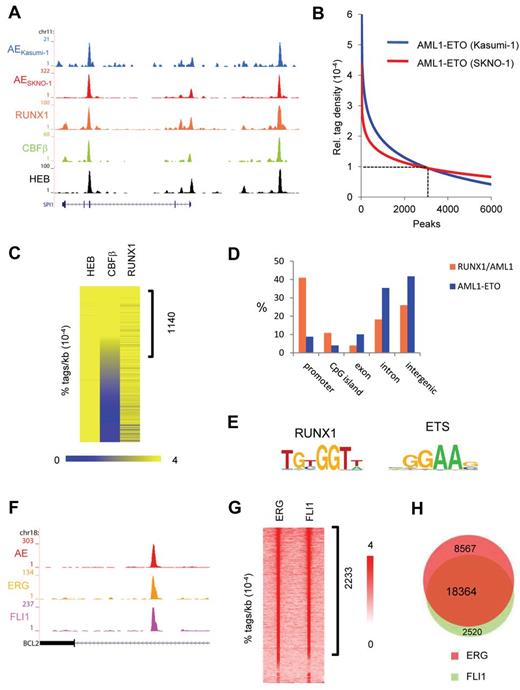

AML1-ETO binding sites coincide with ERG and FLI1 peaks

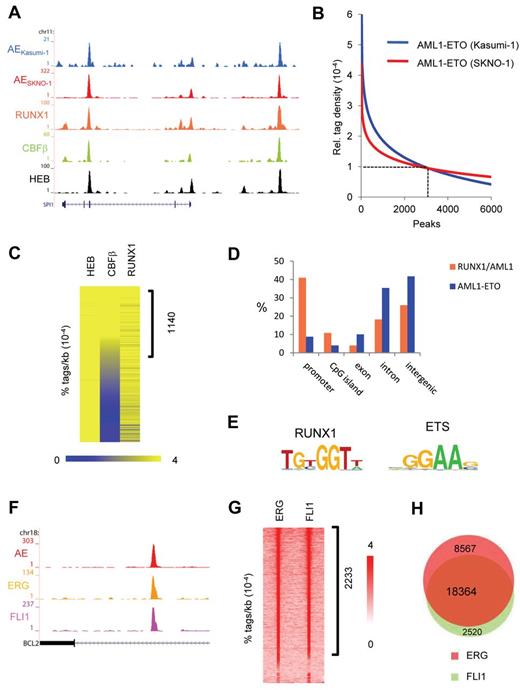

To identify targets of the AML1-ETO oncofusion protein, we developed a specific antibody against the fusion point of AML1-ETO. This antibody (AE) recognizes the fusion of AML1-ETO protein in Western blot analysis (supplemental Figure 1A-B) and shows specificity in AML1-ETO domain analysis (supplemental Figure 1C). The AE antibody was used in ChIP-seq experiments in the AML1-ETO–expressing leukemic cell lines Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 and allowed detection of AML1-ETO binding at many genomic targets, such as at the SPI1 gene (Figure 1A). We used MACS19 at a P value cut-off of 10−8 to identify AML1-ETO binding regions in SKNO-1 and Kasumi-1 cells (supplemental Tables 1 and 2), counted the number of AML1-ETO tags for each identified AML1-ETO binding region in both cell lines, and calculated for each binding region the relative tag density (ie, density at one region divided by average density at all regions). Regression curve analysis (Figure 1B) identified a set of 2754 genomic regions at a cut-off of 0.00010 (> 14 tags/kb) to which AML1-ETO binds with high confidence (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). These binding sites were verified using 2 additional antibodies that recognize different domains within the AML1-ETO protein (supplemental Figure 1C-E), with ChIP-quantitative PCR experiments (supplemental Figure 1F-G) and through comparison with AML1-ETO binding sites previously detected using a C-terminal ETO antibody in Kasumi-1 cells16 (supplemental Figure 1H), suggesting that our high-confidence binding sites represent a set of bona fide AML1-ETO targets.

AML1-ETO and ETS factors bind similar genomic regions. (A) Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO binding site. Blue represents the Kasumi-1 AML1-ETO (AE) ChIP-seq data; red, the SKNO-1 AML1-ETO (AE) data; orange, the RUNX1 data; green, the CBF-β data; and black, the HEB data. (B) AML1-ETO binding sites detected by ChIP-seq in leukemic Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. AML1-ETO peaks were called using MACS (P = .00000001) after which relative AML1-ETO density in Kasumi-1 or SKNO-1 cells was determined at these peaks. Results were sorted according to relative tag density, and the top 6000 peaks displayed in a regression curve. A cut-off was set at a relative tag density of 0.0001 (14 tags/kb). (C) Heatmap displaying HEB, CBF-β, and RUNX1 tag densities at the 2754 high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites. (D) Distribution of the AML1-ETO and RUNX1/AML1 binding site locations relative to RefSeq genes. Locations of binding sites are divided in promoter (− 500 bp to the transcription start site), nonpromoter CpG island, exon, intron, and intergenic (everything else). (E) Overview of the RUNX1 and ETS core binding motif. (F) Overview of the BCL2 AML1-ETO binding site in SKNO-1 cells. Red represents the AML1-ETO (AE) ChIP-seq data; orange, the ERG data; and pink, the FLI1 data. (G) Intensity plot displaying ERG and FLI1 tag densities at high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites. (H) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG and FLI1 binding sites in SKNO-1 cells.

AML1-ETO and ETS factors bind similar genomic regions. (A) Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO binding site. Blue represents the Kasumi-1 AML1-ETO (AE) ChIP-seq data; red, the SKNO-1 AML1-ETO (AE) data; orange, the RUNX1 data; green, the CBF-β data; and black, the HEB data. (B) AML1-ETO binding sites detected by ChIP-seq in leukemic Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. AML1-ETO peaks were called using MACS (P = .00000001) after which relative AML1-ETO density in Kasumi-1 or SKNO-1 cells was determined at these peaks. Results were sorted according to relative tag density, and the top 6000 peaks displayed in a regression curve. A cut-off was set at a relative tag density of 0.0001 (14 tags/kb). (C) Heatmap displaying HEB, CBF-β, and RUNX1 tag densities at the 2754 high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites. (D) Distribution of the AML1-ETO and RUNX1/AML1 binding site locations relative to RefSeq genes. Locations of binding sites are divided in promoter (− 500 bp to the transcription start site), nonpromoter CpG island, exon, intron, and intergenic (everything else). (E) Overview of the RUNX1 and ETS core binding motif. (F) Overview of the BCL2 AML1-ETO binding site in SKNO-1 cells. Red represents the AML1-ETO (AE) ChIP-seq data; orange, the ERG data; and pink, the FLI1 data. (G) Intensity plot displaying ERG and FLI1 tag densities at high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites. (H) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG and FLI1 binding sites in SKNO-1 cells.

To further substantiate our AML1-ETO binding results, we performed additional ChIP-seq experiments to examine RUNX1, HEB, and CBF-β binding, 3 proteins that have previously been suggested to colocalize with AML1-ETO.16,20-23 Using MACS at a P value cut-off of 10−6, this analysis yielded 23 278 RUNX1, 27 501 HEB, and 11 227 CBF-β peaks, respectively (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). At the majority of AML1-ETO binding sites, we detected enrichments of both RUNX1/AML1 and HEB (Figure 1A), whereas CBF-β enrichment was only detected at a subset of AML1-ETO binding sites. Quantitation of RUNX1, HEB, and CBF-β tag densities at AML1-ETO peaks revealed enrichments of both RUNX1/AML1 and HEB at the majority of high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites, whereas CBF-β enrichment was only detected at a subset (∼ 41%) of AML1-ETO binding sites (Figure 1C).

Interestingly, the genomic distribution of the 2754 high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites differs with that of the 23 278 RUNX1/AML1 sites as AML1-ETO localizes predominantly to nonpromoter regions (Figure 1D), whereas RUNX1 localizes preferentially to promoter regions, suggesting that AML1-ETO targets enhancer sites rather than promoter elements.

Motif analysis of the AML1-ETO binding sites revealed that, in conjunction with the RUNX1 motif, the ETS factor core motif GGAAG was enriched in nearly all (99%) of the binding sites (Figure 1E), corroborating previous studies, suggesting that ETS family members might bind similar genomic regions as CBFs.24 As the ETS factor family harbors > 20 representatives that each bind the GGAAG core consensus,25 we investigated which ETS candidate might interplay with the AML1-ETO complex. Analysis of published expression data26 revealed that 3 ETS proteins, TEL, FLI1, and ERG, are highly expressed in AML cells with t(8;21), identifying these as prime candidates to be colocalizing with AML1-ETO.

ChIP-seq analysis in SKNO-1 cells revealed enrichment of FLI1 and ERG at the AML1-ETO binding sites at, for example, the BCL2 gene (Figure 1F), whereas the presence of TEL could not be addressed because of lack of a suitable ChIP-seq grade antibody. Quantitation of ERG and FLI1 tag densities at AML1-ETO peaks revealed high levels of ERG and FLI1 at ∼ 81% of AML1-ETO binding sites (Figure 1G), whereas the remaining sites bound either ERG or FLI1. We also observed binding of both ERG and FLI1 at numerous other genomic regions that are not occupied by AML1-ETO. Overlapping the 26 931 ERG and 20 884 FLI1 binding regions confirmed this observation and suggested that ERG and FLI1 bind similar genomic loci (Figure 1H; supplemental Figure 1I).

Interestingly, ChIP-seq analysis in the PML-RAR-α–expressing leukemic cell line NB4, an APL cell line that expresses high levels of FLI1 and no detectable ERG, revealed FLI1 binding at many PML-RAR-α occupied genomic regions, such as the PRAM1 and GALNAC4S-6ST genes (supplemental Figure 2A). Counting the FLI1 tags within a previously defined set of 2722 PML-RAR-α binding regions27 revealed increased FLI1 binding at 71% of PML-RAR-α peaks (supplemental Figure 2B). Because recently the ETS factor SPI1 (PU.1) was identified as a binding partner of the PML-RAR-α oncofusion protein complex in a U937 overexpression cell system,6 these results suggest that, as for AML1-ETO, the PML-RAR-α oncofusion protein preferentially binds ETS factor occupied regions.

AML1-ETO binds and localizes to ETS factor binding sites

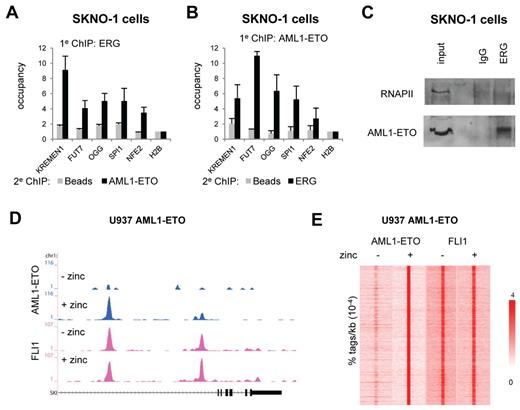

Our AML1-ETO/ETS factor ChIP-seq results extend a recent study that showed AML1 and ERG protein-protein interaction and binding of similar genomic regions in the mouse model cell line HPC-7.28 Indeed, re-ChIP analysis confirmed occupancy of AML1-ETO and ERG at similar genomic regions in SKNO-1 cells and a direct interaction of endogenous AML1-ETO and ERG in coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Figure 2A-C). Moreover, overexpression of ERG and AML1-ETO in the MCF7 breast cancer cell line, which does not endogenously express these proteins (supplemental Figure 3A), revealed binding of both proteins to the same genomic regions (supplemental Figure 3B-C), suggesting that simultaneous binding of AML1-ETO and ERG to genomic regions does not need the contribution of other hematopoietic-specific factors.

AML1-ETO is recruited to ETS factor binding sites. (A-B). Re-ChIP experiments validating AML1-ETO and ERG binding to the same locus. Five binding sites were selected and validated for AML1-ETO/ERG binding by re-ChIP using either ERG antibodies in the first round of ChIP followed by a second round using AML1-ETO and no antibodies (A) or AML1-ETO antibodies in the first round of ChIP followed by a second round using ERG and no antibodies (B). (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of AML1-ETO with ERG. Immunoprecipitations were performed in SKNO-1 cells using IgG and ERG antibodies and analyzed by Western using RNAPII and AML1-ETO antibodies. (D) ChIP-seq using U937 cells expressing (+ zinc) or not expressing (− zinc) AML1-ETO. Overview of the SKI AML1-ETO binding site in U937 AML1-ETO cells. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; and pink, the FLI1 data. (E) Intensity plot showing the tag density of AML1-ETO and FLI1 tags within a 10-kb window around AML1-ETO binding sites in U937 AML1-ETO cells treated or untreated with zinc.

AML1-ETO is recruited to ETS factor binding sites. (A-B). Re-ChIP experiments validating AML1-ETO and ERG binding to the same locus. Five binding sites were selected and validated for AML1-ETO/ERG binding by re-ChIP using either ERG antibodies in the first round of ChIP followed by a second round using AML1-ETO and no antibodies (A) or AML1-ETO antibodies in the first round of ChIP followed by a second round using ERG and no antibodies (B). (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of AML1-ETO with ERG. Immunoprecipitations were performed in SKNO-1 cells using IgG and ERG antibodies and analyzed by Western using RNAPII and AML1-ETO antibodies. (D) ChIP-seq using U937 cells expressing (+ zinc) or not expressing (− zinc) AML1-ETO. Overview of the SKI AML1-ETO binding site in U937 AML1-ETO cells. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; and pink, the FLI1 data. (E) Intensity plot showing the tag density of AML1-ETO and FLI1 tags within a 10-kb window around AML1-ETO binding sites in U937 AML1-ETO cells treated or untreated with zinc.

To investigate whether ETS factors are co-recruited by AML1-ETO or facilitate AML1-ETO binding, we extended our analysis to an inducible U937 cell line (UAE) that on zinc addition expresses AML1-ETO (supplemental Figure 3D).29 Genome-wide profiling of AML-ETO after 5 hours of zinc induction revealed numerous binding sites, such as at the SKI and NFE2 genes (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 3E). Using MACS, we identified 9635 AML1-ETO binding sites in zinc–treated UAE cells (Figure 2E left; supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Further ChIP-seq experiments in UAE cells, which express high levels of FLI1 (and no detectable levels of ERG), revealed that FLI1 is already present at the AML1-ETO binding sites before expression of the oncofusion protein at, for example, the SKI and NFE2 genes (Figure 2D; supplemental Figure 3E), suggesting that FLI1 demarcates potential AML1-ETO binding sites. Indeed, quantitation of FLI1 tag densities at AML1-ETO peaks confirmed the observation that AML1-ETO binding sites are defined by FLI1 binding (Figure 2E right), suggesting that FLI1 might represent a protein that facilitates AML1-ETO binding.

ETS factors recruit AML1-ETO

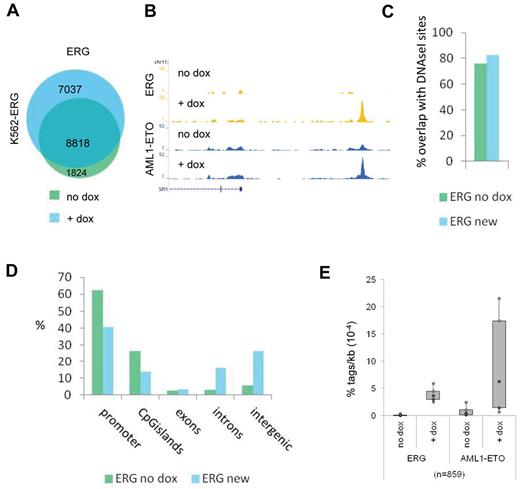

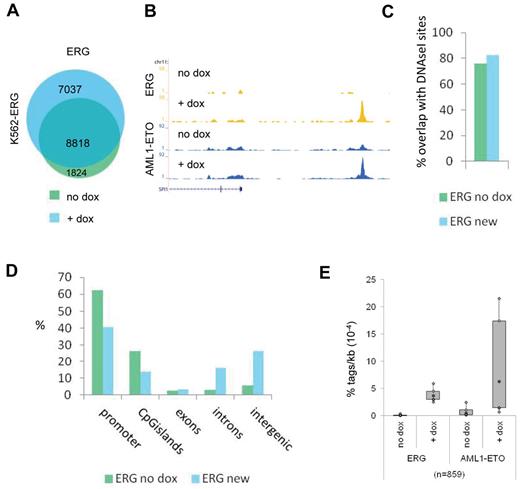

To further investigate the interplay of AML1-ETO and ETS factors, we used a doxycyclin-inducible ERG K562 cell line,30 which shows lower ERG expression before treatment and increased ERG expression after 72 hours doxycyclin treatment (supplemental Figure 4A). We transfected these cells 24 hours before harvesting with an expression vector that results in abundant expression of the AML1-ETO protein (supplemental Figure 4A). We used ChIP-seq and MACS at a P value cut-off of 10−6 to identify all ERG binding sites before and after dox induction and identified 10 642 and 15 855 binding events, respectively (Figure 3A; supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Interestingly, we detect 7037 new ERG binding sites that appear after doxycyclin treatment (Figure 3A), for example, at the SPI1 enhancer region and the TAF12 promoter (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4B). Comparison with public DNAseI-seq data in K562 cells (see UCSC “regulation” tracks) revealed that the majority of new ERG binding sites, similar as the ERG binding sites present before dox induction, localize to accessible regions (Figure 3C) and that, compared with ERG binding sites before dox induction, more intronic and intergenic regions than promoters are targeted (Figure 3D).

ETS factors facilitate AML1-ETO binding. (A) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG binding sites in K562-ERG cells not treated, or treated for 72 hours with dox. (B) ChIP-seq using K562-ERG cells expressing high levels (+ dox) or low levels (no dox) of ERG. Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO/ERG binding site in K562-ERG cells, transfected 24 hours before harvesting with AML1-ETO. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; and yellow, the ERG data. (C) Overlap of DNAseI accessibility defined regions with ERG binding sites present before dox induction (ERG no dox) and ERG binding sites that appear after dox induction (ERG new). (D) Distribution of the ERG “no dox” and ERG “new” binding site locations relative to RefSeq genes. (E) Boxplot showing the tag density of AML1-ETO and ERG within “new” ERG binding sites in K562-ERG cells transfected with AML1-ETO and treated or untreated with dox.

ETS factors facilitate AML1-ETO binding. (A) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG binding sites in K562-ERG cells not treated, or treated for 72 hours with dox. (B) ChIP-seq using K562-ERG cells expressing high levels (+ dox) or low levels (no dox) of ERG. Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO/ERG binding site in K562-ERG cells, transfected 24 hours before harvesting with AML1-ETO. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; and yellow, the ERG data. (C) Overlap of DNAseI accessibility defined regions with ERG binding sites present before dox induction (ERG no dox) and ERG binding sites that appear after dox induction (ERG new). (D) Distribution of the ERG “no dox” and ERG “new” binding site locations relative to RefSeq genes. (E) Boxplot showing the tag density of AML1-ETO and ERG within “new” ERG binding sites in K562-ERG cells transfected with AML1-ETO and treated or untreated with dox.

Subsequent AML1-ETO ChIP-seq analysis revealed that AML1-ETO was recruited to the SPI1 and TAF12 regions on dox induction (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 4B). Of the 7037 new ERG binding sites, 6178 harbor low levels of ERG before induction, whereas 859 did not show ERG binding in the uninduced state (Figure 3E; supplemental Figure 4C). Interestingly, at the 6178 “increased” ERG binding sites, AML1-ETO is localized before dox induction and moderately increased (supplemental Figure 4C), whereas at the 859 “new” ERG binding regions AML1-ETO is strongly increased after dox treatment (Figure 3E). Together, these results suggest that AML1-ETO is localized to regions that harbor the ERG protein and that ERG facilitates AML1-ETO binding.

ERG silencing results in decreased AML1-ETO and RUNX1 expression

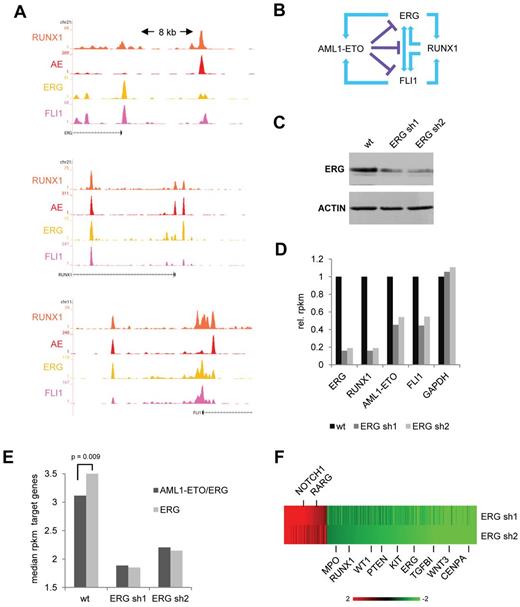

Our genome-wide binding data revealed that RUNX1 binds the upstream regulatory region of ERG and FLI1, whereas, vice versa, ERG and FLI1 bind near the promoter of RUNX1 (Figure 4A), suggesting a positive feed forward loop. Conversely, ERG/FLI1 potentially regulates AML-ETO expression and AML1-ETO binds at sites regulating ERG/FLI1 expression. As examining recent AML1-ETO siRNA silencing experiments16 showed (small) increases in expression of RUNX1, ERG, and FLI1 (supplemental Figure 5A), these observations suggest that AML-ETO interferes with the ERG/FLI1/RUNX1 positive feed forward loop (Figure 4B).

ERG regulates expression of AML1-ETO target genes. (A) Overview of the RUNX1, FLI1, and ERG upstream regulatory regions in SKNO-1 cells. Orange represents the RUNX1 data; red, the AE data; yellow, the ERG data; and pink, the FLI1 ChIP-seq data. (B) Schematic representation of a suggested positive feed forward loop between RUNX1 and FLI1/ERG and the potential interference of AML1-ETO. (C) Western analysis of ERG expression in wt and ERG silenced (+ dox) SKNO-1 cells. (D) Expression level (as assessed by RPKM values) of ERG, RUNX1, FLI1, and AML1-ETO in wt SKNO-1 cells and SKNO-1 cells that express different ERG silencing constructs. (E) Median RPKM values of ERG target genes bound (black) or not bound (gray) by AML1-ETO in wild-type SKNO-1 cells compared with 2 ERG silenced (+ dox) SKNO-1 cell lines. (F) Heatmap showing expression changes in genes bound by AML1-ETO/ERG at the promoter or within intragenic regions.

ERG regulates expression of AML1-ETO target genes. (A) Overview of the RUNX1, FLI1, and ERG upstream regulatory regions in SKNO-1 cells. Orange represents the RUNX1 data; red, the AE data; yellow, the ERG data; and pink, the FLI1 ChIP-seq data. (B) Schematic representation of a suggested positive feed forward loop between RUNX1 and FLI1/ERG and the potential interference of AML1-ETO. (C) Western analysis of ERG expression in wt and ERG silenced (+ dox) SKNO-1 cells. (D) Expression level (as assessed by RPKM values) of ERG, RUNX1, FLI1, and AML1-ETO in wt SKNO-1 cells and SKNO-1 cells that express different ERG silencing constructs. (E) Median RPKM values of ERG target genes bound (black) or not bound (gray) by AML1-ETO in wild-type SKNO-1 cells compared with 2 ERG silenced (+ dox) SKNO-1 cell lines. (F) Heatmap showing expression changes in genes bound by AML1-ETO/ERG at the promoter or within intragenic regions.

To examine whether ETS factors, in this instance ERG, have a role in regulation of AML1-ETO and/or RUNX1 expression, we performed shRNA-mediated silencing experiments using 2 previously reported ERG shRNA constructs.31 RNA-seq and Western analysis after shRNA silencing of ERG in SKNO-1 cells revealed reduced expression of ERG in these cells (Figure 4C-D). ERG silenced SKNO-1 cells showed reduced proliferation in growth assays (supplemental Figure 5B), suggesting ERG is needed to maintain the full leukemogenic potential of t(8;21) cells.

In agreement with an activating role of ERG in RUNX1/AML1-ETO transcription, RPKM values for RUNX1 and AML1-ETO were also reduced (Figure 4D; supplemental Figure 5C), whereas also FLI1 expression levels are down. Together, our results suggest that ETS factors are not only needed to facilitate AML1-ETO binding but also for driving AML1-ETO expression in t(8;21) AML.

To examine the effect of ERG silencing on AML1-ETO target genes, we compared in wild-type SKNO-1 cells expression of all genes having AML1-ETO/ERG promoter or intragenic binding (and most likely represent targets for regulation by AML1-ETO) with genes only bound by ERG. This analysis revealed that, compared with the 13 578 genes targeted by ERG alone, the median expression is lower for the 1803 genes bound by AML1-ETO/ERG (Figure 4E left; supplemental Figure 5D), suggesting that ERG regulated genes targeted by AML1-ETO are on average less transcribed.

Of the subset of 436 AML1-ETO/ERG target genes that show a higher than 2-fold change in expression using ERG silencing construct sh1 or sh2 (supplemental Tables 1 and 2), the majority (339), including RUNX1 and KIT, goes down in expression (Figure 4F), whereas only 97 increase 2-fold or more. Interestingly, silencing of ERG reduces expression of all ERG target genes (bound as well as not bound by AML1-ETO) to a similar level (Figure 4E), suggesting that ERG is involved in transcriptional activation and that AML1-ETO modulates expression of ERG target genes, on average reducing but not fully repressing transcriptional activation by ERG.

AML1-ETO and ERG binding coincides in AML primary patient blasts

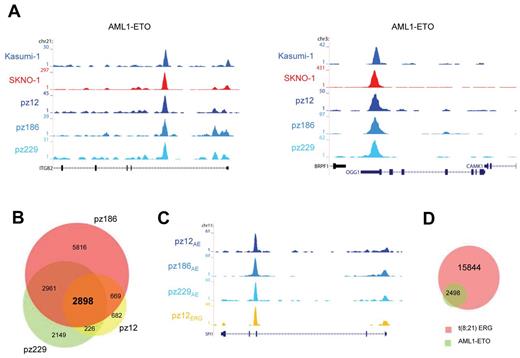

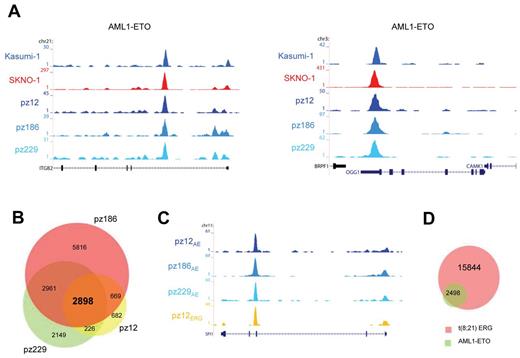

To examine whether the high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites found in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells are also bound by AML1-ETO in patient AML cells with t(8,21), we performed ChIP-seq using the AE antibody. We obtained AML1-ETO peaks at similar genomic regions in these primary AML blasts (n = 3) as in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells, for example, at the ITGB2 and OGG1 genes (Figure 5A). We performed MACS at a P value cut-off of .000001 to identify all AML1-ETO binding sites and detected 4475, 12 344, and 8234 sites in patients 12, 186, and 229, respectively (supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

AML1-ETO binding sites in patient AML CD34+ cells with t(8;21). (A) Overview of the ITGB2 and OGG1 AML1-ETO binding sites. Two cell lines (SKNO-1 and Kasumi-1) and blasts of 3 AML patients with t(8;21) were used in ChIP-seq experiments using a specific antibody that could recognize AML1-ETO (AE). (B) Venn diagram representing the overlap of binding sites detected in patients AML cells with t(8; 21); n = 3. (C) Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO binding site. A blast from one AML patient with t(8;21) was used in ChIP-seq experiments using a specific antibody that could recognize ERG and compared with the ChIP-seq results of AML1-ETO (AE) in 3 patient blasts with t(8;21). (D) Venn diagram representing the overlap of the 2898 common AML1-ETO binding sites detected in 3 patients with t(8;21) and ERG binding sites detected in one patient (pz12) with t(8;21).

AML1-ETO binding sites in patient AML CD34+ cells with t(8;21). (A) Overview of the ITGB2 and OGG1 AML1-ETO binding sites. Two cell lines (SKNO-1 and Kasumi-1) and blasts of 3 AML patients with t(8;21) were used in ChIP-seq experiments using a specific antibody that could recognize AML1-ETO (AE). (B) Venn diagram representing the overlap of binding sites detected in patients AML cells with t(8; 21); n = 3. (C) Overview of the SPI1 AML1-ETO binding site. A blast from one AML patient with t(8;21) was used in ChIP-seq experiments using a specific antibody that could recognize ERG and compared with the ChIP-seq results of AML1-ETO (AE) in 3 patient blasts with t(8;21). (D) Venn diagram representing the overlap of the 2898 common AML1-ETO binding sites detected in 3 patients with t(8;21) and ERG binding sites detected in one patient (pz12) with t(8;21).

Overlapping the binding regions of the 3 patient samples (Figure 5B) revealed a common set of 2898 regions (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). As these AML common regions probably include key binding sites for AML1-ETO–induced oncogenic transformation, we performed functional analysis of the associated genes using GO annotation clustering (supplemental Figure 6). This revealed high enrichment scores (> 3) for genes involved in cell death, structural processes, and hematopoietic differentiation.

To examine whether ETS factors bind similar genomic loci as AML-ETO also in primary AML blasts carrying t(8,21) as observed for SKNO-1 cells, we performed ChIP-seq using the ERG antibody with cells from an AML patient (pz12) that harbors t(8;21). We again found binding of both ERG and AML1-ETO at similar genomic regions in primary patient cells, for example, at the SPI1 gene (Figure 5C). Using MACS, we identified 18 342 ERG binding sites in this patient and confirmed that the majority of the 2898 common AML1-ETO binding sites identified in the AML cells bind similar loci as ERG (Figure 5D), corroborating and extending the AML1-ETO/ETS factor interplay to primary patient blasts.

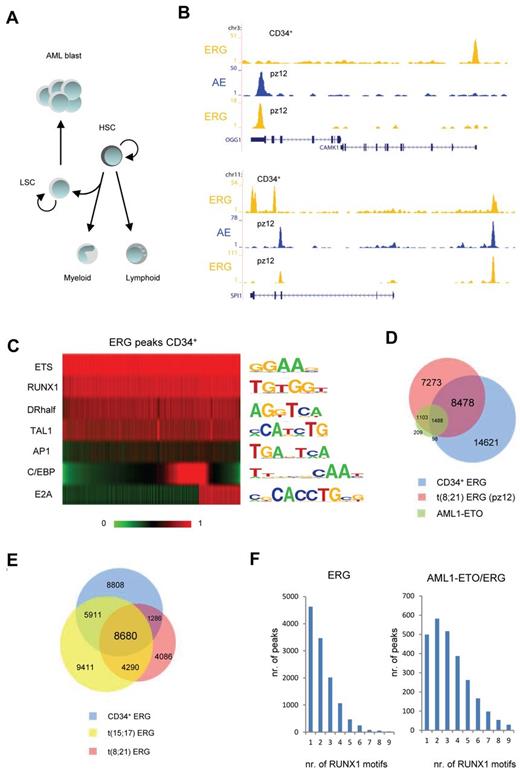

Distinct ERG distribution in normal CD34+ and AML1-ETO–expressing cells

As our results suggest that ERG and FLI1 flag AML1-ETO docking sites, we wondered whether the ETS bound regions are laid down in normal hematopoietic CD34+ cells, which represent a mixture of cells having the potential to differentiate toward both the myeloid and lymphoid lineage (Figure 6A).32 Therefore, ChIP-seq was performed to determine the ETS binding profile in normal CD34+ human progenitors. We focused our analysis on ERG as these CD34+ progenitors express high levels of ERG and only low levels of FLI1. Our analysis revealed ERG binding at nearly 25 000 binding regions, such as at the CAMK1 transcription start site and on the SPI1 gene (Figure 6B). Motif analysis of the sequences underlying ERG binding sites in CD34+ cells confirmed the presence of the ETS factor core motif, validating our binding sites as genuine ETS binding. Moreover, it revealed the presence of multiple consensus sequences for hematopoietic regulators, such as RUNX1, TAL1, nuclear receptor half sites, and AP1 factors (Figure 6C). Binding motifs for 2 proteins, E2A found in 6637 ERG binding sites and C/EBP in 8388 ERG binding sites specifying lymphoid and myeloid lineages, respectively, were enriched in mostly nonoverlapping subpopulations of CD34+ ERG binding regions, suggesting indeed that ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells may predefine regulatory sites for differentiation toward both the myeloid and lymphoid lineage.

ERG identifies genomic regions important in hematopoietic development and has cell type specific binding profiles. (A) Schematic representation of normal and aberrant hematopoietic differentiation. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cells; and LSC, leukemic stem cells. (B) Overview of the OGG1, CAMK1, and SPI1 ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells and ERG and AML1-ETO (AE) binding sites in blast cells from a patient with t(8;21). Yellow represents the ERG ChIP-seq data; and blue, the AML1-ETO data. (C) Heatmap display of motif scores of DNA sequences underlying ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells. (D) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG (pz12) and the common AML1-ETO binding sites of t(8;21) patient AML cells and ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells. (E) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells, t(15;17) APL cells, and t(8;21) AML patient cells (pz12). (F) Number of RUNX1 motifs present in t(8;21) patient ERG binding sites not occupied by AML1-ETO (left) or present in AML1-ETO binding sites (right).

ERG identifies genomic regions important in hematopoietic development and has cell type specific binding profiles. (A) Schematic representation of normal and aberrant hematopoietic differentiation. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cells; and LSC, leukemic stem cells. (B) Overview of the OGG1, CAMK1, and SPI1 ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells and ERG and AML1-ETO (AE) binding sites in blast cells from a patient with t(8;21). Yellow represents the ERG ChIP-seq data; and blue, the AML1-ETO data. (C) Heatmap display of motif scores of DNA sequences underlying ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells. (D) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG (pz12) and the common AML1-ETO binding sites of t(8;21) patient AML cells and ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells. (E) Venn diagram representing the overlap of ERG binding sites in normal CD34+ cells, t(15;17) APL cells, and t(8;21) AML patient cells (pz12). (F) Number of RUNX1 motifs present in t(8;21) patient ERG binding sites not occupied by AML1-ETO (left) or present in AML1-ETO binding sites (right).

Comparison of the CD34+ ERG binding sites with those detected in t(8;21) blasts revealed the presence of ERG at many common sites, such as at the SPI1 upstream region (Figure 6B). However, also differential ERG binding sites were detected, such as at the OGG1 promoter and the SPI1 gene (Figure 6B). Of the ERG binding sites detected in CD34+, only 40% overlapped with those in t(8;21) cells (Figure 6D), suggesting that ERG profiles might be cell type specific. This observation could be extended to analysis of the t(15;17) translocation (Figure 6E), confirming that ERG profiles could to a large extend be cell type specific.

Motif analysis of the 8376 newly gained ERG binding sites in t(8;21) cells revealed no major shifts in the presence of consensus sequences for ETS, RUNX1, TAL1, nuclear receptor half sites, and AP1 factors compared with normal CD34+ cells (supplemental Figure 7A), although less C/EBP and E2A consensus sequences were found. However, we noticed that a large fraction of AML1-ETO protein targets newly gained ERG binding sites (Figure 6D), which becomes even more apparent when examining AML1-ETO binding in t(8;21) cell lines (supplemental Figure 7B), where 69% of AML1-ETO protein targets ERG binding sites that are specific for SKNO-1 cells in the comparison with CD34+ cells. Together, these results suggest that AML1-ETO preferentially targets cell type specific ERG bound genomic regions.

Despite that all ERG binding sites have a RUNX1 consensus sequence, AML1-ETO binds only to a subset suggesting that these regions harbor additional molecular characteristics. As oligomerization of AML1-ETO has been suggested as essential for leukemogenesis,33,34 we hypothesized that targeting of AML1-ETO could be dependent on the number of RUNX1 sequences underlying the ERG binding regions. Counting the number of RUNX1 motifs in ERG only binding sites compared with those that bound also AML1-ETO revealed a statistical significant difference (P = 1.8 × 10−5) in the distribution of the number of binding sites. Whereas most overlapping AML1-ETO and ERG binding sites have 2-4 consensus RUNX1 motifs (Figure 6F right), other ERG binding sites have generally 1 or 2 (Figure 6F left). These results suggest that the underlying DNA template supports the binding of oligomerized AML1-ETO protein.

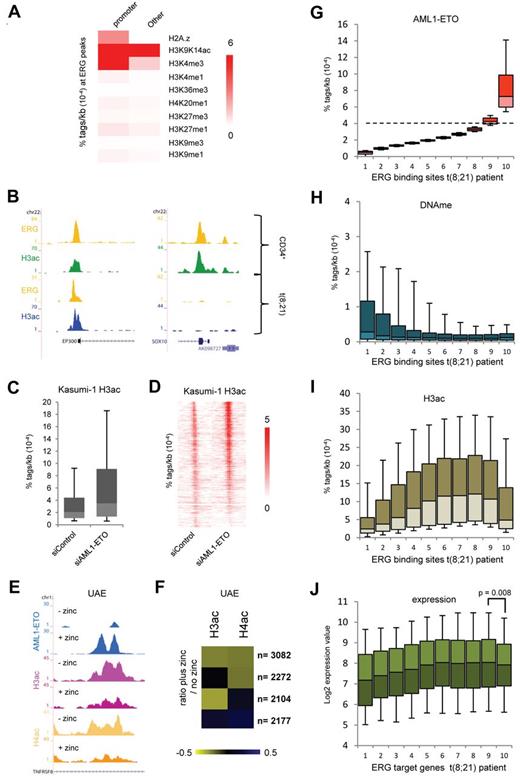

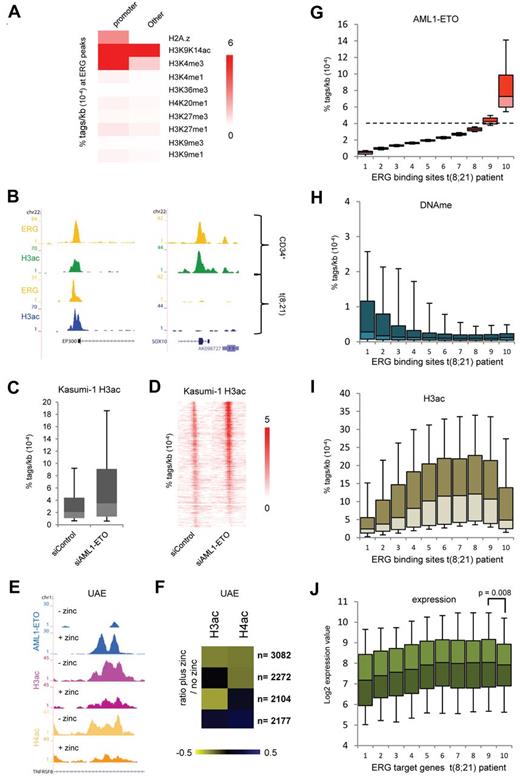

AML1-ETO/ERG binding sites have decreased H3 acetylation levels

To investigate whether oncofusion proteins could alter the epigenetic makeup of ERG binding sites, we correlated the epigenetic modifications at these genomic regions. To this aim, we performed ChIP-seq for H3K9K14ac in normal CD34+ cells and included 9 previously published histone modification profiles of hematopoietic progenitor cells35 in our analysis. This revealed a strong correlation of ERG binding sites with H3K9K14ac (Figure 7A), whereas other modifications are not enriched or only in subsets of ERG binding regions, such as H3K4me3, which is specifically enriched at ERG binding sites located at promoters. Indeed, at the ERG binding sites that are present at the p300 promoter and the SOX10 exon, we detect H3 acetylation in normal CD34+ cells (Figure 7B). The ERG site at the p300 promoter is still present in t(8;21) cells, whereas ERG binding and H3K9K14ac are lost at the SOX10 gene.

ERG defines H3 acetylation signatures in normal CD34+ and t(8;21) blast cells. (A) Heatmap displaying median tag densities of a variety of chromatin modifications at ERG binding sites that are present in normal CD34+ cells. (B) Overview of the SOX10 and P300 genes in normal CD34+ and AML cells with t(8;21). Yellow represents the ERG ChIP-seq data; green, the H3K9K14ac using normal CD34+ cells; and blue, the H3K9K14ac data using patient AML CD34+ cells with t(8;21). (C-D) Boxplot (C) and intensity plot (D) showing the H3K9ac tag density at high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites in control and AML1-ETO silenced Kasumi-1 cells. (E) ChIP-seq using U937 cells expressing (+ zinc) or not expressing (− zinc) AML1-ETO. Overview of the TNFRSF8 AML1-ETO binding site in U937 AML1-ETO cells. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; purple, the H3ac data; and yellow, the H4ac data. (F) Heatmap displaying the log2 ratio of H3ac or H4ac tags at AML1-ETO target regions in zinc treated cells versus untreated cells. (G-I) Boxplots showing the density of AML1-ETO (G), MethylCap-DNAme (H), and H3ac (I) tags in patient AML t(8;21) cells within 10 bins of ERG binding sites (pz12) that are ranked according to AML1-ETO tag density. The dotted line in panel G separates the ERG sites not bound by AML1-ETO (bins 1-8) from those bound by AML1-ETO (bin 10). (J) Boxplot showing log2 expression values of the genes targeted by both AML1-ETO and ERG (predominantly bin 10) or ERG alone in 22 t(8;21) patients.

ERG defines H3 acetylation signatures in normal CD34+ and t(8;21) blast cells. (A) Heatmap displaying median tag densities of a variety of chromatin modifications at ERG binding sites that are present in normal CD34+ cells. (B) Overview of the SOX10 and P300 genes in normal CD34+ and AML cells with t(8;21). Yellow represents the ERG ChIP-seq data; green, the H3K9K14ac using normal CD34+ cells; and blue, the H3K9K14ac data using patient AML CD34+ cells with t(8;21). (C-D) Boxplot (C) and intensity plot (D) showing the H3K9ac tag density at high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites in control and AML1-ETO silenced Kasumi-1 cells. (E) ChIP-seq using U937 cells expressing (+ zinc) or not expressing (− zinc) AML1-ETO. Overview of the TNFRSF8 AML1-ETO binding site in U937 AML1-ETO cells. Blue represents the AE ChIP-seq data; purple, the H3ac data; and yellow, the H4ac data. (F) Heatmap displaying the log2 ratio of H3ac or H4ac tags at AML1-ETO target regions in zinc treated cells versus untreated cells. (G-I) Boxplots showing the density of AML1-ETO (G), MethylCap-DNAme (H), and H3ac (I) tags in patient AML t(8;21) cells within 10 bins of ERG binding sites (pz12) that are ranked according to AML1-ETO tag density. The dotted line in panel G separates the ERG sites not bound by AML1-ETO (bins 1-8) from those bound by AML1-ETO (bin 10). (J) Boxplot showing log2 expression values of the genes targeted by both AML1-ETO and ERG (predominantly bin 10) or ERG alone in 22 t(8;21) patients.

AML1-ETO has been suggested to modulate H3 acetylation via recruitment of HDACs to target genes.36,37 To investigate the link between AML1-ETO binding and histone (de)acetylation, we analyzed previously published H3K9ac ChIP-seq profiles in siRNA-mediated AML1-ETO–silenced Kasumi-1 cells.16 This analysis revealed that, at the majority (75%) of our 2754 high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites, H3ac levels are increased on silencing of AML1-ETO (Figure 7C-D). In addition, we profiled H3ac and H4ac in a U937 cell line that on zinc addition expresses AML1-ETO (UAE).29 This revealed decreased acetylation at many of the Zn-induced AML1-ETO binding sites, for example, at the TNFRSF8 gene (Figure 7E). Counting the number of H3ac and H4ac tags within all the AML1-ETO target regions before and after zinc induction allowed identification of 4 groups (Figure 7F); the largest group (n = 3082) showed decreases in both H3ac and H4ac, whereas in other groups only H4ac (n = 2272) or H3ac decreased (n = 2104) or H3ac and H4ac moderately increased (n = 2177). Together, these results reveal that, at a very large number (77%) of binding sites, AML1-ETO binding induces decreases in H3 and/or H4 acetylation, whereas, vice versa, silencing of AML1-ETO increases histone acetylation levels, suggesting that AML1-ETO recruits HDAC activities to its binding sites.

To investigate whether AML1-ETO recruits HDAC activities to ERG binding sites in patient samples, we analyzed in t(8;21) blasts from 2 patients (pz186 and pz229) the H3ac and DNAme levels at all ERG binding sites. For this, we ranked the ERG binding sites according to AML1-ETO tag density (Figure 7G) and divided them in 10 bins of equal size. As such, bins 1-8 represent background binding, while especially bin 10 represents high-confidence AML1-ETO binding regions. For most bins, we observed an inverse correlation between H3ac levels and DNA methylation (Figure 7H-I). In contrast, bin 10, which has the highest AML1-ETO tag count and thus the highest level of AML1-ETO, shows reduced levels of H3ac. Interestingly, analyzing expression of the gene targets of the binding regions represented in the different bins using a published dataset on 22 t(8;21) patients26 revealed reduced expression of the genes targeted by AML1-ETO and ERG (bin 10) compared with genes bound only by ERG (Figure 7J). Together, these results imply that an important molecular strategy of the oncofusion protein AML1-ETO involves targeting of histone deacetylation activities to hematopoietic regulatory sites bound by ERG.

Discussion

Many breakpoints involved in specific chromosomal translocations have been cloned over the years. In most cases, however, the role of the chimeric oncofusion proteins in tumorigenesis has not been fully elucidated. Here we used antibodies specifically recognizing the AML1-ETO fusion point as well as 2 antibodies recognizing different parts of the ETO protein in ChIP-seq to identify AML1-ETO binding and identified 2754 high-confidence, mostly nonpromoter, binding sites in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. In addition, we analyzed genome-wide RUNX1/AML1, HEB, and CBF-β binding and could show enrichments of both RUNX1/AML1 and HEB at all high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites. The binding of AML1-ETO and RUNX1 to similar regions was further corroborated by the observation that all AML1-ETO binding sites harbor the RUNX1 DNA consensus motif, suggesting that AML1-ETO occupies sites normally bound by wild-type RUNX1. In contrast, CBF-β, for which its role in AML1-ETO leukemogenesis is still not fully resolved,38 was only detected at a subset of AML1-ETO binding sites.

Analysis of the high-confidence AML1-ETO binding sites showed an abundance of ETS factor consensus motifs at nearly every position. ChIP-seq with FLI1 and ERG antibodies revealed the presence of these ETS factors at AML1-ETO binding sites in SKNO-1 cells, a finding that could be corroborated and extended to a primary AML blast with t(8;21). In addition to AML1-ETO, ETS factor co-occupancy could also be identified at sites bound by the oncofusion protein PML-RAR-α, substantiating in the APL-derived NB4 cells previous findings that identified co-occurrence of the ETS factor SPI1 with PML-RAR-α in U937 overexpression PML-RAR-α cells.6

Interestingly, using an AML1-ETO-inducible cell system revealed that AML1-ETO is recruited to sites preoccupied by FLI1, uncovering at least some of the ETS factors as proteins that facilitate binding of other proteins. Further analysis in an ERG inducible cell system showed that AML1-ETO binds additional genomic regions when these are premarked by ERG binding. Moreover, we could show that AML1-ETO and ERG directly interact. Together, these data suggest that ETS factors have a pioneering function, demarcating accessible genomic regions to which oncofusion proteins, such as AML1-ETO, can be recruited in a cell type-specific fashion. The function of ERG in providing a docking platform for other hematopoietic regulators is further substantiated by the recent identification of a loss of function ERG mutant39 that still binds DNA but is suggested to have lost the potential to interact with other proteins and from ChIP-seq studies in mice that suggest that ERG and FLI1 bind with a variety of other hematopoiesis–associated proteins28,40 to similar loci. Interestingly, our results show that ERG is not only needed in facilitating AML1-ETO binding but also for driving AML1-ETO expression in t(8;21) AML. Such dual function of ERG in AML1-ETO leukemogenesis implies that silencing of this ETS factor will affect many AML1-ETO target genes, which we indeed could confirm through ERG silencing experiments.

Previous studies suggested that AML1-ETO represses genes activated by ETS factors, such as ELF441 and ETS1.42 Here comparison of expression in wild-type SKNO-1 cells of genes bound by both AML1-ETO/ERG or by ERG alone revealed that expression is reduced of those genes targeted by AML1-ETO/ERG, suggesting that AML1-ETO negatively affects, but does not completely block, expression. In contrast, silencing of ERG results in a substantial further decrease, suggesting that, whereas ERG is involved in transcriptional activation, AML1-ETO modulates expression of ERG target genes, on average reducing but not fully repressing transcriptional activation.

Increased expression of ERG and FLI1 in normal karyotype AMLs is associated with poor prognosis,43-45 suggesting that aberrant regulation by ERG or FLI1 might be a general mechanism associated with leukemogenesis. The molecular mechanisms behind these findings are unclear. Our results suggest that binding of ETS factors is cell type specific and that it is associated with histone hyperacetylation. Increased levels of ERG/FLI1 expression might result in changes in global histone acetylation because of binding of these ETS factors to more sites. In addition, our results reveal that overexpression of ETS factors results in localization of these proteins to many previously inaccessible genomic regions and thereby facilitate binding of secondary proteins. This function might be crucial in preventing normal hematopoietic differentiation in transformed cells and supporting leukemogenesis in high ERG or FLI1-expressing AMLs.

In addition to oncofusion protein-expressing cells, we assessed ETS factor binding in normal hematopoietic CD34+ cells. Normal CD34+ cells have the potential to differentiate along the lymphoid and myeloid lineages dependent on the culture conditions used, whereas the t(8;21) and APL cells are transformed and probably blocked at a certain stage of the myeloid differentiation program. Analysis and comparison of ERG binding sites in these cell types revealed that ERG binding sites are marked with “active” H3 acetylation. Extending these results to cells that express oncofusion proteins revealed that a main molecular strategy of AML1-ETO involves targeting of histone deacetylation activities to ERG bound hematopoietic regulatory sites. Interestingly, our study shows that PML-RAR-α binding regions are also occupied by ETS factors, and previously we reported that PML-RAR-α has similar epigenetic effects,27 suggesting that AML1-ETO and PML-RAR-α use similar molecular mechanisms to block differentiation. Indeed, recruitment of histone deacetylation activities to hyperacetylated ETS factor regulatory sites can be expected to have a significant impact on transcription and epigenetic organization and probably represents a crucial event in the transformation process. Moreover, these observations also highlight the potential of using specific HDAC inhibitors or other epigenetic-based drugs in AML treatment. Specific targeting of the epigenetic modifications that underlie “normal” ETS factor binding sites or targeting the acetylase/deacetylase containing complexes46 might provide an attractive approach to therapeutically eradicate leukemic cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank E. Megens, Y. Tan, and A. Kaan for technical assistance and S. van Heeringen, A. Brinkman, and K. Francoijs for bioinformatic support. SKNO-1 cells were a kind gift of Michael Lübbert, the AML1-ETO cDNA from Carol Stocking, the ERG expression construct from Jussi Taipale, and the K562-ERG cell line from Claudia Baldus.

All ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data can be downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no. GSE23730.

This work was supported by The Netherlands Bioinformatics Centre, the European Union (LSHC-CT-2005-518417 “Epitron”; HEALTH-F2-2007-200620 “CancerDip”), the Dutch Cancer Foundation (KWF KUN 2008-4130 and KUN 2009-4527), The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-VIDI 917.11.322, J.M.), the Epigenomics Flagship Project EPIGEN, and l'Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca contro il cancro. A.M. was supported by Pier Paolo Parnigotto, University of Padova, Italy and CARIPARO (scholarship).

Authorship

Contribution: J.H.A.M. and H.G.S. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript; and all authors designed methods, performed the experiments, contributed to the manuscript preparation, and gave approval of the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Joost H. A. Martens, Radboud University, Department of Molecular Biology, Faculty of Science, Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; e-mail: j.martens@ncmls.ru.nl; and Hendrik G. Stunnenberg, Radboud University, Department of Molecular Biology, Faculty of Science, Nijmegen Centre for Molecular Life Sciences, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands; e-mail: h.stunnenberg@ncmls.ru.nl.