Abstract

Cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (CPB) is associated with a high incidence of IgG Abs against platelet factor 4/heparin (PF4/H) complexes by day 6 after surgery. These Abs are associated with an immune-mediated adverse drug reaction, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Although the early onset of the anti-PF4/H IgG response is compatible with a secondary immune response, the rapid decline of Ab titers thereafter is not. To shed light on the origin of these Abs, in the present study, we prospectively compared the kinetics of these Abs with that of Abs against 2 recall Ags and to that of autoantibodies in 166 CPB patients over 4 months. Surgery induced strong inflammation, as shown by an increase in mean C-reactive protein levels. Consistent with previous studies, anti-PF4/H IgG optical density transiently increased between baseline and day 10 (P < .001; not associated with C-reactive protein levels), followed by a decrease over the next months. In contrast, concentrations of antidiphtheria toxin IgG and antitetanus toxin IgG increased constantly over the 4 months after surgery by 25%-30%. IgG autoantibodies did not change. Therefore, the transient kinetics of the anti-PF4/H IgG response resembled neither that of recall Abs nor that of IgG autoantibodies, but rather showed a unique profile.

Introduction

Platelet factor 4 (PF4), a chemokine stored in large amounts in platelet α granules, is rapidly released on platelet activation. The positively charged molecule forms tetramers that readily associate with polyanions such as heparin, forming large PF4/heparin (PF4/H) complexes. PF4 complexed to heparin exposes neoepitopes that can be targeted by antibodies (Abs). The resulting immune complexes can give rise to heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), the most common adverse drug reaction affecting blood cells. HIT is clinically relevant because it results in a paradoxical prothrombotic state.1

The immunobiology of the anti-PF4/H Ab response is not well understood. It exhibits unusual kinetics that fit neither a primary immune response nor a typical secondary immune response: in 2 studies of orthopedic surgery patient Abs of all classes, IgM, IgG, and IgA, but especially IgG, appeared from day 4 after the beginning of heparin exposure, even in heparin-naive patients.2,3 This has also been shown for trauma surgery patients4 and cardiac surgery patients.5 However, in the latter patient groups, anti-PF4/H Abs were usually only determined starting from day 6. This early onset of IgG production strongly indicates that patients have been pre-immunized against PF4/polyanion complexes, and we have shown recently that this probably occurs via PF4-coated bacteria.6,7 In fact, in vitro data and a mouse model suggest that PF4 might have a role in bacterial host defense mechanisms.7 The risk of developing anti-PF4/H Abs is influenced by patient related factors; for example, it is strongly increased when heparin is given within the context of trauma or inflammation.6,8 Trauma and inflammation might provide additional “danger signals” facilitating activation of the involved B cells.

Although HIT patients usually have anti-PF4/H IgG, only a minority of patients with an anti-PF4/H response develop overt HIT.9 Interestingly, during the acute phase of HIT, some anti-PF4/H Abs show characteristics of autoantibodies in that they bind to PF4 on platelets even in the absence of heparin.10,11 This autoimmune feature of HIT is most pronounced in patients with “delayed onset HIT,”12 in whom HIT symptoms typically occur several days after cessation of heparin.13 Therefore, HIT shows features of a secondary immune response, an autoimmune response, and it might be part of a general activation of a host defense system triggered by inflammation. Conversely, anti-PF4/H Ab titers typically decrease rapidly,3,14 even though a secondary immune response should lead to persisting high titers of IgG Abs.

Anti-PF4/H IgG Abs are generated in approximately 50% of patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (CPB). In addition to necessitating the administration of heparin for anticoagulation during extracorporeal circulation, CPB poses a substantial challenge to the immune system because of mechanical tissue damage, anesthesia and other medications, extensive contact with foreign surfaces, and ischemia-reperfusion injury to tissues, all of which induce strong inflammation with rapid increases of serum cytokines such as IL6, IL8, TNFα, and IL10.15-18

In the present study, we investigated whether the anti-PF4/H IgG response after CPB is part of a general disinhibition of autoreactive B cells (general loss of tolerance) or if it is associated with polyclonal activation of memory B cells against recall Ags.19-22 We followed CPB patients prospectively for more than 4 months after surgery to compare the kinetics of the anti-PF4/H IgG response with that of Abs targeting other autoantigens and Abs specific for the recall Ags tetanus toxoid (TT) and diphtheria toxin (DT). Our results show clearly that the kinetics of the anti-PF4/H Ab response has a unique profile: its rapid but transient increase was distinct from that of the Ab response to the recall Ags TT and DT, which gradually increased over the whole observation period without showing the decrease in titers typically observed for anti-PF4/H Abs. Neither was it part of a general break in tolerance, because an increase in the titer of Abs directed against other typical autoantigens was not observed.

Methods

Patients

Patients had been enrolled in a previously reported, prospective study in adult patients requiring CPB surgery.23-25 Serum samples had been collected from these patients before surgery and on days 3 and 10 after surgery. At discharge from the hospital, patients were invited to participate in this long-term study and to provide an additional blood sample at least 4 months after surgery. This time period corresponds to approximately 6 half-lives of serum IgG. After this time period, more than 98% of the Abs generated perioperatively should have been degraded. This would allow assessment of the long-term effects of CPB surgery on the B-cell response. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Ernst-Moritz-Arndt University in Greifswald, Germany.

Ab assays and CRP measurement

Anti-PF4/H IgG Abs were assessed by ELISA26 and reactivities are given as optical densities (ODs). Because several patients showed an OD > 0.5 in the baseline sample, we defined as responders patients experiencing an increase of the OD at day 10 of ≥ 0.5 compared with the baseline OD values. Patients with a lower increase or no increase at all were classified as nonresponders. Concentrations of anti-DT and anti-TT recall Abs were measured using the Serion ELISA classic kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The ODs were compared with an approved standard and are given in international serum units (IU). For the determination of IgM or IgG total serum concentrations, MaxiSorp 96-well plates (Nunc) were coated overnight at 4°C with goat anti–human Ig (SouthernBioTech). After washing, free protein-binding sites were blocked with 2% goat normal serum in PBS/Tween. Serum was diluted with the blocking buffer, added to the sample wells, and incubated for 1 hour. Bound Abs were detected with goat anti–human IgM-HRPOD (Dianova) or goat anti–human IgG-HRPOD (Dianova). The plates were developed with OptEIA TMB substrate reagent (BD Biosciences), stopped with 2N H2SO4, and read at 450 nm. Concentrations were determined with an appropriate standard curve.

To screen for autoantibodies, we used binding to the human epidermoid carcinoma cell line HEp2 as a readout, which allowed the detection of Ab binding to a large spectrum of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and cytoskeletal autoantigens. Human sera were diluted 1:100 in 20% FCS/PBS and incubated on HEp2-ANA slides (INOVA Diagnostics) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, bound Abs were visualized with 1 drop of FITC-labeled anti–human IgG conjugate with ready-to-use Evan's blue (INOVA Diagnostics). Slides were exposed for an equal length of time and pictures taken with an Axio Imager A.1 microscope and Spot Advanced Version 4.6 software (Carl Zeiss).

C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured by a standard high-sensitivity assay (CRPL3 and Cobas Integra 800; Roche) as part of the standard postsurgical monitoring protocol.

Statistical analysis

The Friedman test with Dunn posttest, Mann-Whitney U test, or Wilcoxon matched pairs test were used for statistical analysis, along with GraphPad Prism Version 5 software.

Results

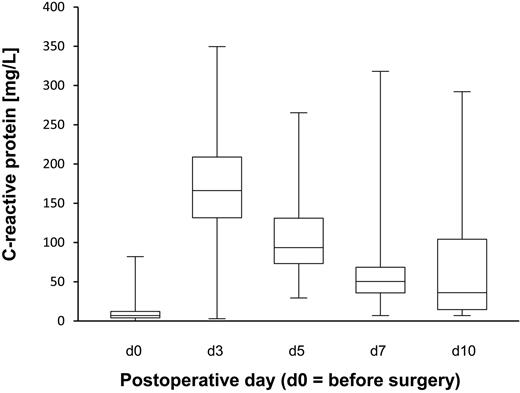

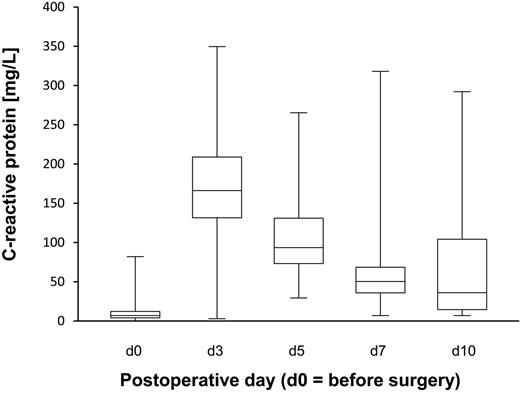

In total, 166 patients were enrolled in this long-term study. As expected, CPB surgery induced a strong inflammatory response. The patients' maximal CRP serum concentrations 3 days after surgery averaged 167 mg/dL (range, 3-350; the reference value for healthy controls was < 1 mg/dL; Figure 1). The CRP concentrations on day 3 (maximum) were not correlated with the increases of total or Ag-specific IgG concentrations described in the following 3 paragraphs (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Kinetics of the CRP concentrations in CPB patients. CRP was measured pre- and postoperatively. The figure illustrates that the patients developed transient strong inflammation after CPB surgery (normal levels are < 1 mg/dL). The box plots indicate the median, upper, and lower quartiles and the range.

Kinetics of the CRP concentrations in CPB patients. CRP was measured pre- and postoperatively. The figure illustrates that the patients developed transient strong inflammation after CPB surgery (normal levels are < 1 mg/dL). The box plots indicate the median, upper, and lower quartiles and the range.

Kinetics of the anti-PF4/H response

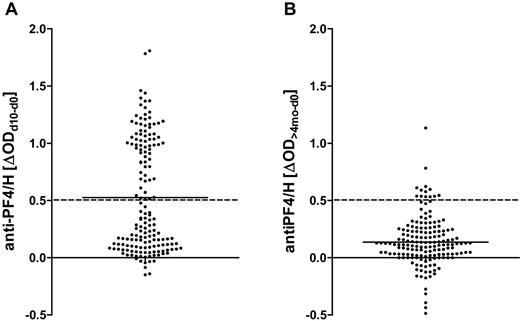

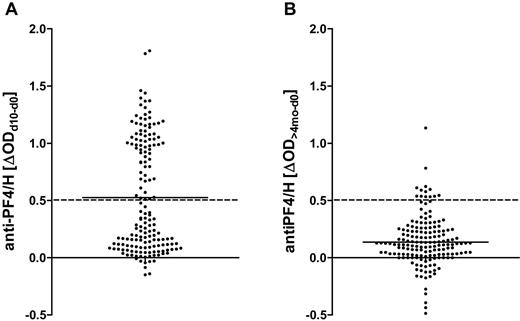

Anti-PF4/H IgG increased by at least 0.5 OD by day 10 after surgery in 72 patients (responders; Figure 2A). When these patients were reassayed at > 4 months, anti-PF4/H ODs had decreased and responders became indistinguishable from nonresponders (Figure 2B), consistent with earlier observations of the transient nature of the anti-PF4/H Ab response.8,14,27 Ninety-four patients were nonresponders (ΔOD < 0.5; Figure 2A).

Transient increase of IgG binding to PF4/H in CPB patients after surgery. A total of 166 patients undergoing CPB surgery were recruited into the study. Anti-PF4/H IgG binding was determined preoperatively, 10 days later, and reanalyzed around 4 months postoperatively. The differences between the OD values on day 10 or > 4 months and baseline OD values are shown. The means are shown by solid lines. (A) Patients were classified into responders or nonresponders according to the increase in anti-PF4/H IgG serum binding from day 0 to day 10, with a threshold of ΔOD = 0.5 (hatched line). (B) At approximately 4 months after CPB, anti-PF4/H Abs had decreased and responders became indistinguishable from nonresponders. Very few patients remained above the threshold for responders (hatched line).

Transient increase of IgG binding to PF4/H in CPB patients after surgery. A total of 166 patients undergoing CPB surgery were recruited into the study. Anti-PF4/H IgG binding was determined preoperatively, 10 days later, and reanalyzed around 4 months postoperatively. The differences between the OD values on day 10 or > 4 months and baseline OD values are shown. The means are shown by solid lines. (A) Patients were classified into responders or nonresponders according to the increase in anti-PF4/H IgG serum binding from day 0 to day 10, with a threshold of ΔOD = 0.5 (hatched line). (B) At approximately 4 months after CPB, anti-PF4/H Abs had decreased and responders became indistinguishable from nonresponders. Very few patients remained above the threshold for responders (hatched line).

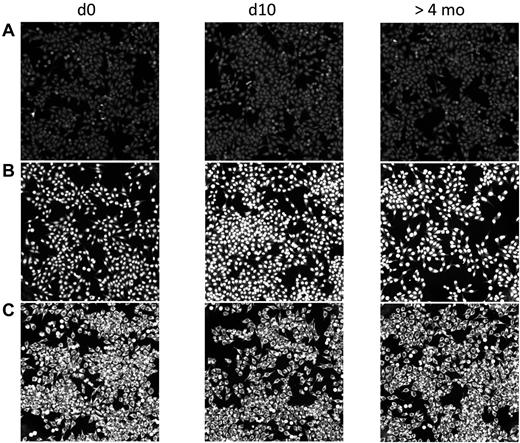

Kinetics of autoreactive Abs

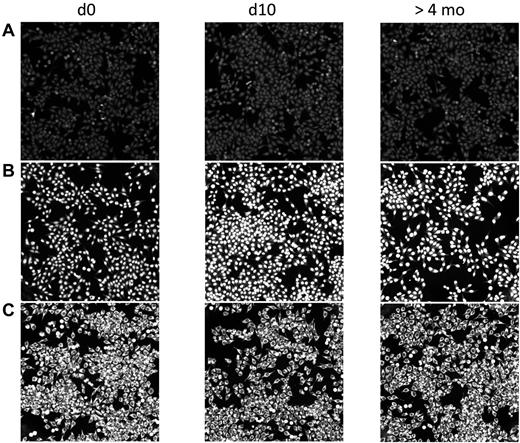

In contrast to the rapid transient increase in anti-PF4/H IgG, serum Ab binding to typical autoantigens did not change after CPB surgery. When we screened the sera for anticellular Abs using binding to HEp2 cells as a readout, the majority of patients, 124 of 166 (74.7%), did not show any sign of autoreactivity during the entire study period (Figure 3A); 22 patients had weakly binding IgG autoantibodies (not shown), and 20 patients exhibited strong IgG binding with typical patterns of autoreactivity (Figure 3B-C). In the patients with autoreactive Abs, these Abs were already present in the baseline sample taken before surgery. Neither the pattern nor the binding intensities of these IgG autoantibodies changed during the postsurgical period. This renders it very unlikely that the anti-PF4/H Ab response is part of a general activation of autoreactive B cells.

No change in autoreactive Abs in CPB patients after surgery. Human sera before (d0) and after CPB (d10 and > 4 months) were diluted in 20% FCS/PBS and incubated on commercially available HEp2-ANA slides. Bound Abs were visualized with FITC-conjugated anti–human IgG. The staining did not reveal any increase of autoreactive Abs postoperatively. Patient A is representative of the majority of patients (124 of 166) who showed no autoreactive Abs at any time. The 2 patients shown in panels B and C already had Abs against nuclear or cytoplasmic Ags before surgery. These did not change in quality or quantity after surgery. Twenty of the 166 patients had similar findings.

No change in autoreactive Abs in CPB patients after surgery. Human sera before (d0) and after CPB (d10 and > 4 months) were diluted in 20% FCS/PBS and incubated on commercially available HEp2-ANA slides. Bound Abs were visualized with FITC-conjugated anti–human IgG. The staining did not reveal any increase of autoreactive Abs postoperatively. Patient A is representative of the majority of patients (124 of 166) who showed no autoreactive Abs at any time. The 2 patients shown in panels B and C already had Abs against nuclear or cytoplasmic Ags before surgery. These did not change in quality or quantity after surgery. Twenty of the 166 patients had similar findings.

Polyclonal B-cell activation

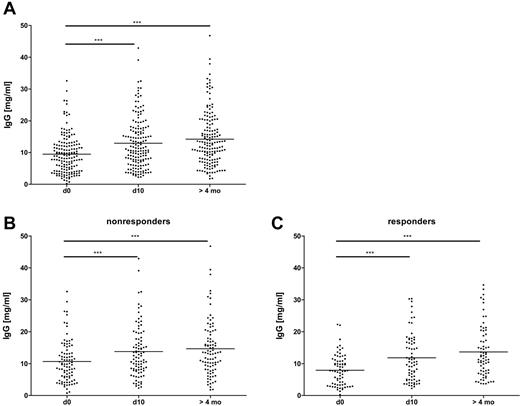

Total IgG serum concentration increased by a mean of 30% between baseline and day 10 after surgery (P < .001; Table 1) and was even higher in the sample taken more than 4 months after surgery (P < .001; Figure 4A). This increase was observed in both the anti-PF4/H responders and the nonresponders (Figure 4B-C), who did not differ in total IgG levels reached at day 10 and at > 4 months (for day 10, P = .25 and for the sample taken at > 4 months, P = .16 by Mann-Whitney U test). At baseline, anti-PF4/H responders had significantly lower IgG concentrations than nonresponders (P = .0047, Figure 4B-C and supplemental Figure 2). This difference was because of those patients, whose baseline IgG concentration exceeded 15 mg/mL, which was the case in 21 responders and 5 nonresponders. The 26 patients maintained or even increased their very high IgG serum concentrations over the whole study period (supplemental Figure 3). Yet neither the baseline IgG concentrations nor the changes in total IgG serum concentration correlated with the increase of anti-PF4/H ODs (supplemental Figure 4A-B). Furthermore, the 26 patients with high baseline IgG concentrations did not differ from the others with regard to their general inflammatory response as determined by serum CRP concentrations at day 3 after surgery (supplemental Figure 5).

Moderately increased serum concentrations of total IgG in CPB patients over the observation period. Serum IgG concentrations were determined by ELISA before (d0), 10 days (d10), and > 4 months after CPB. The Friedman test with a Dunn posttest revealed significant increases of IgG over time in all patients (A), with no major difference in the pattern between nonresponder (B) and responder (C) groups. However, the mean value for IgG in responders to PF4/H at baseline was lower than in nonresponders. This was because of a larger proportion of patients with total IgG levels > 15 mg/mL (see also supplemental Figure 2; n = 166). ***P < .001.

Moderately increased serum concentrations of total IgG in CPB patients over the observation period. Serum IgG concentrations were determined by ELISA before (d0), 10 days (d10), and > 4 months after CPB. The Friedman test with a Dunn posttest revealed significant increases of IgG over time in all patients (A), with no major difference in the pattern between nonresponder (B) and responder (C) groups. However, the mean value for IgG in responders to PF4/H at baseline was lower than in nonresponders. This was because of a larger proportion of patients with total IgG levels > 15 mg/mL (see also supplemental Figure 2; n = 166). ***P < .001.

The kinetic of total serum IgM concentrations was very similar to the changes in total serum IgG concentrations (supplemental Figure 6).

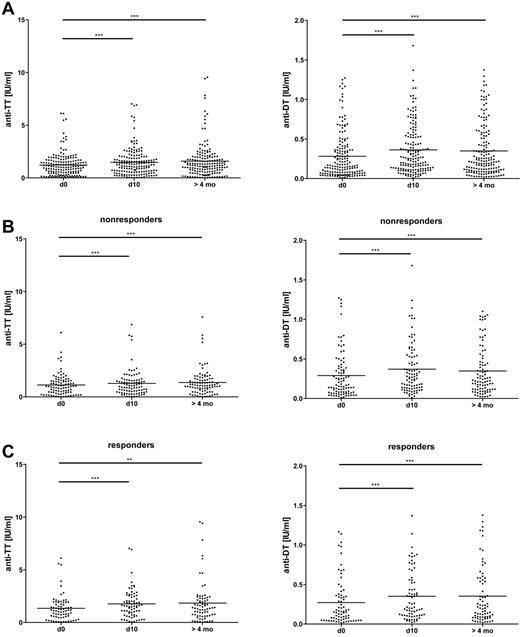

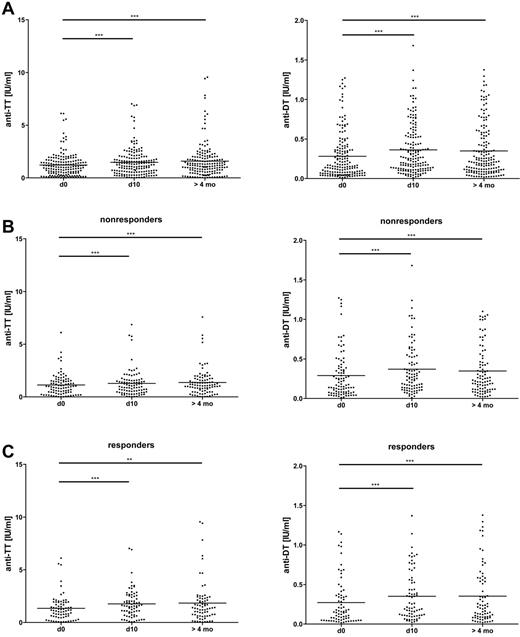

We then focused on established B cell memory for the classic recall Ags TT and DT and measured a small but significant increase of IgG binding to these Ags over time (P < .001 in both cases; Figure 5A), with no difference between anti-PF4/H responders and nonresponders (for the sample taken at > 4 months, P = .49 for TT and P = .35 for DT by Mann-Whitney U test; Figure 5B-C and Table 2). In addition, on an individual basis, the changes in IgG binding to the recall Ags TT and DT and to PF4/H were not correlated (supplemental Figure 7A-B). Therefore, the long-lasting effects of CPB surgery on total and Ag-specific Ig serum concentrations differed markedly from the transient kinetics of IgG binding to PF4/H.

Moderately increased IgG binding to the recall Ags DT and TT in CPB patients after surgery. Serum concentrations of Abs binding to DT and TT were determined by ELISA before (d0), 10 days (d10), and > 4 months after CPB. The Friedman test with a Dunn posttest revealed a significant increase of the concentrations over time in the patient group as a whole (A). The increase was similar in nonresponders (B) and responders (C). Means are shown as solid lines (n = 166). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Moderately increased IgG binding to the recall Ags DT and TT in CPB patients after surgery. Serum concentrations of Abs binding to DT and TT were determined by ELISA before (d0), 10 days (d10), and > 4 months after CPB. The Friedman test with a Dunn posttest revealed a significant increase of the concentrations over time in the patient group as a whole (A). The increase was similar in nonresponders (B) and responders (C). Means are shown as solid lines (n = 166). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Discussion

The results of the present study provide further evidence that the immune response to PF4/H after major surgery has distinct features that can be explained by neither a general response of autoreactive B cells nor a moderate polyclonal activation of memory B cells to recall Ags after CPB surgery.

The immune response to PF4/H is of great interest because it mediates HIT, the most frequent adverse drug reaction involving blood cells.28 To the best of our knowledge, there is no other iatrogenic immune reaction that occurs so frequently in adults. After CPB surgery, approximately 50% of the patients are expected to develop an anti-PF4/H immune response. Because the immune response to PF4/H always occurs in the second week of heparin treatment, clinical studies are feasible. In this study, we systematically assessed the acute and long-term B-cell response against PF4/H in comparison with immune responses to other Ags in humans under “real-world” conditions. Because IgG has a serum half-life of approximately 21 days, we followed patients for more than 4 months. After this time, more than 98% of the serum IgG that was present before surgery or produced perioperatively will have decayed. Therefore, any changes in the plasma cell pool, in particular generation of new long-lived plasma cells or loss of preexisting plasma cells, were detectable by changes of serum Ab titers.

CPB surgery elicited a pronounced increase of IgG binding to PF4/H that was preceded by a strong inflammatory response. However, there was no correlation between the serum concentrations of CRP 3 days after surgery and the subsequent increase in anti-PF4/H IgG binding. We were not able to differentiate whether the involved B cells require a more specific signal than broad activation of inflammation or if the inflammatory stimulus during cardiac surgery is so strong that maximal activation of the involved B cells may already be reached, even in patients with a relatively low increase in CRP. This could be studied by correlation of the CRP levels and anti-PF4/H Ab response in patients undergoing less invasive procedures.

It remains uncertain whether the anti-PF4/H immune response should be classified as an autoimmune response or as an alloimmune response to a neoepitope. Although PF4 presents repetitive epitopes when complexed with heparin,29 it remains an endogenous protein. In addition, there is increasing evidence that anti-PF4/H Abs can cross-react with PF4 bound to platelets without the need for additional heparin.11 In some patients, HIT occurs even several days after heparin is no longer administered (delayed-onset HIT),13,14 that is, in the absence of circulating pharmaceutical heparin. This would be compatible with an in vivo autoimmune response. However, this feature may be restricted to a subset of platelet-activating anti-PF4/H IgG Abs occurring in patients with symptomatic HIT.9-11 Very rarely, HIT occurs spontaneously.30,31 These patients either had an underlying autoimmune disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus or had a recent bacterial infection.32

We reasoned that the increase of anti-PF4/H Abs after CPB surgery might be part of a general activation of (natural) autoreactive B cells derived, for example, from marginal zone B cells or from B1 cells. It has already been shown in a mouse model that such B cells are triggered by tissue injury and ischemia reperfusion.33 In addition, Tiller et al discovered an abundance of autoreactive specificities among class-switched memory B cells derived from B2 cells. During homeostasis, these cells do not give rise to Ab-secreting plasma cells, implying stringent control.34 This balance, however, could be disturbed by major surgery and inflammation. We performed the same screening assay for the detection of autoreactive Abs as in the Tiller study34 (IgG binding to HEp2 cells) and found that, after CPB surgery, the control of this autoreactive B-cell population was clearly maintained. Serum IgG binding to other autoantigens increased neither in prevalence nor in intensity and there was no correlation between the presence of autoantibodies and generation of anti-PF4/H Abs. Our findings rule out that an entire class of “silent” IgG+ memory B cells with autoreactive potential is unleashed by CPB surgery.

Recently, we observed the appearance of anti-PF4/H Abs during bacterial sepsis in mice.7 Moreover, the natural immune response to PF4/H in the general population (ie, subjects not being treated with heparin) is strongly associated with periodontal disease.35 Anti-PF4/H Abs might therefore be part of a bacterial host defense mechanism. In this case, PF4/H complexes could represent a recall Ag against which a secondary Ab response is triggered by heparin treatment in conjunction with PF4 release induced by trauma and/or inflammation. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that anti-PF4/H IgG Abs occurred in approximately half of the patients in the present study until day 623,24 and HIT typically occurs between days 5 and 10 after surgery.24,36,37 These observations are difficult to reconcile with the notion of a primary immune response.

The immune response pattern after cardiac surgery has been studied previously. Two groups of investigators found a decrease of total IgG concentrations after CPB, which in the study by Lante et al, amounted to 30% on the first day after surgery.38,39 Considering the serum half-life of IgG, approximately 20 days, this rapid effect must be due to hemodilution and/or sequestration of IgG,39 because changes in IgG production can account for a decrease of maximally 3% within 1 day.

Furthermore, memory B cells are highly responsive to polyclonal stimuli such as microbial products, CD40 ligation, and common γ-chain cytokines.19 It has been proposed that polyclonal activation regularly boosts humoral memory and contributes to its maintenance in the absence of cognate Ag.19-22 We therefore assessed in the present study whether CPB surgery and the associated inflammatory response led to an Ag-independent activation of B cells by measuring the total serum IgG concentrations and response to 2 prototypic recall Ags, TT and DT. These Ags were selected because most subjects are vaccinated against these proteins and possess specific memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells that maintain the constant serum Ab concentrations.40 Obviously, there will be no Ag-driven reactivation of TT- or DT-specific memory B cells during CPB surgery.

IgG serum concentrations moderately increased over baseline by day 10 after surgery and continued to rise over the next months. This strongly indicates that cardiac surgery has long-term effects on Ab-producing plasma cells. Focusing on Ag-specific Abs, Lante et al observed that the concentration of TT-binding IgG had moderately increased by day 5 after CPB surgery.38 Our present data corroborate and extend their observations, showing that the increase was stable over several months and that anti-DT Abs exhibit a similar behavior. Therefore, stimulation of Ab production to recall Ags appears to be a more general feature of CPB intervention, indicating that memory B cells are indeed polyclonally activated in patients undergoing major surgery.

If the Ab titers to DT and TT had shown a transient increase, similar to the kinetics of the PF4/H response, the latter could have been attributed to polyclonal activation of memory B cells, too. However, this was not the case, so the polyclonal activation of memory B cells cannot fully explain the anti-PF4/H IgG response to CPB surgery. First, a continuous moderate increase characterized IgG binding to the “classic” recall Ags, whereas in many subjects, the anti-PF4/H response was initially strong or even dramatic. This strong initial increase can easily explained by Ag exposure. However, the PF4/H IgG titers declined and after 4 months there was no longer any difference between responders and nonresponders. This is consistent with our previous findings that IgG+ memory B cells with specificity for TT but not for PF4/H are found in the peripheral blood of CPB patients before surgery.41 Furthermore, from the transience of its kinetics, it is obvious that long-lived plasma cells do not readily develop during an anti-PF4/H response.41 Finally, there is evidence that an anti-PF4/H immune response can be elicited in MyD88-knockout mice that are deficient in their response to many polyclonal B-cell stimuli.42 The anti-PF4/H response shows a very different pattern compared with the polyclonal response to classic recall Ags. This suggests that the anti-PF4/H response is Ag-driven, which is likely because the immune system was challenged with heparin during and after surgery but not with DT and TT.

In addition to polyclonal activation of B cells, for example via TLRs,19 a shift in the T-cell subset composition could also contribute to alterations in the Ab response after major surgery. After an initial systemic inflammatory response, major surgery (including cardiac surgery) leads to an anti-inflammatory state characterized by transient lymphocytopenia with impairment of T-cell activation and down-regulation of CD14 on monocytes.15,43,44 When stimulated ex vivo, PBMCs and T lymphocytes obtained from such patients released less IFN-γ, shifting the balance from a Th-1 toward a Th-2 profile. This alteration can be (partially) reversed by the addition of IL-12.45,46 Although there was no net increase in the number of IL4-secreting cells nor in the amount of released IL4, DiPiro et al have measured increases of IgE concentration and eosinophil count in the blood after CPB surgery or sepsis.47 This is intriguing in view of recent reports that eosinophils48 are constituents of the niche for long-lived plasma cells. Megakaryocytes49 are also part of this niche, and it is very well known that a transient increase in platelet counts is typical after major surgery. Therefore, activation of the B cells producing anti-PF4/H Abs might be caused in part by down-regulation of the adaptive immune system. We already hypothesized that the anti-PF4/H immune response is an evolutionary ancient defense mechanism.7 Perhaps transient lymphocytopenia provides a favorable environment for these B cells, which are silenced again when the T-cell population recovers. This may explain the transience of anti-PF4/H Ab production. The recent finding that IL-10 promoter polymorphisms are associated with the risk for anti-PF4/H immune response50 would fit with such a regulatory feedback loop.

The observation that subjects with very high IgG plasma levels at baseline had a much lower risk for responding to PF4/H is interesting. Assuming a causal relationship, one may speculate that the high baseline IgG levels are because of a stimulated adaptive immune system, which may have a negative feedback on those B cells that produce PF4/H Abs. Because these patients did not have measurable anti-PF4/H Abs before surgery, neutralization of PF4/H complexes is not a likely explanation. Furthermore, with regard to their general inflammatory response as measured by CRP levels, patients with high baseline IgG concentrations did not differ from others, ruling out a general dampening effect of the IgG on inflammation such as that which is observed after therapeutic application of high-dose IV IgG.51-53 Potentially, a high serum IgG serum concentration reflects an ongoing (secondary) immune response. A vigorous plasma cell response could interfere with anti-PF4/H–plasma cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival, because the spleen has a finite capacity to sustain plasma cells.54 However, most nonresponders had baseline IgG serum concentrations well below 15 mg/mL, and those patients with high IgG levels at baseline did not experience a decrease of their IgG concentrations over time, as would be expected from a fading secondary Ab response (supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, at this stage, there is no final answer as to how very high IgG concentrations may prevent the development of anti-PF4/H Abs.

Our present findings have also implications of clinical relevance: Clearly, CPB did not interfere with long-term immune memory. It caused no loss of anti-DT and anti-TT protection and in fact moderately boosted the memory response.55-57 On its own, such a small boost may be of little biologic significance, but when repeated, this mechanism could stabilize memory. Obviously, the BM niches for Ag-specific long-lived plasma cells remained intact after CPB surgery. Either the polyclonally activated B cells were unable to displace resident long-lived plasma cells or they replaced them with newly generated plasma cells of the same Ag specificity.40,58-61 These findings are in good agreement with the results of a recent long-term study addressing humoral memory to vaccination Ags, in which extremely long serum half-lives (in the range of decades) of protective serum Ab responses were demonstrated.62

In summary, the results of the present study suggest that the increase in anti-PF4/H IgG after CPB surgery is an Ag-driven B-cell response that cannot be explained by a secondary response, a memory response, or general nonspecific activation of memory B cells. Furthermore, the autoimmune-like features of some anti-PF4/H IgG Abs cannot be explained by a general activation of B cells with autoreactive potential. This provides further evidence for our hypothesis that the anti-PF4/H Ab response shows a rather unique profile and may belong to a class of ancient humoral defense mechanisms at the interface between the innate and adaptive immune system. In the case of heparin administration, this response mechanism is misdirected to the platelet surface.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Erika Friebe for expert technical assistance.

This work was supported by the University Medicine Greifswald (FVMM), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, GRK 840), and the Zentrum für Innovationskompetenz Humorale Immunreaktionen bei Herz-Kreislauf Erkrankungen (ZIK HIKE), Federal Ministry of Education and Research (03Z2CK1, ZIK-HIKE 03Z2CI1).

Authorship

Contribution: C.P. and S.S. performed the experiments; C.P., B.M.B., and A.G. wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the study design and the data evaluation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Prof Dr Andreas Greinacher, Institut für Immunologie und Transfusionsmedizin, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universität Greifswald, 17489 Greifswald, Germany; e-mail: greinach@uni-greifswald.de.