Abstract

Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) induce peripheral tolerance by direct presentation to CD8 T cells (TCD8). We demonstrate that LECs mediate deletion only via programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) ligand 1, despite expressing ligands for the CD160, B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator, and lymphocyte activation gene-3 inhibitory pathways. LECs induce activation and proliferation of TCD8, but lack of costimulation through 4-1BB leads to rapid high-level expression of PD-1, which in turn inhibits up-regulation of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor that is necessary for TCD8 survival. Rescue of tyrosinase-specific TCD8 by interference with PD-1 or provision of costimulation results in autoimmune vitiligo, demonstrating that LECs are significant, albeit suboptimal, antigen-presenting cells. Because LECs express numerous peripheral tissue antigens, lack of costimulation coupled to rapid high-level up-regulation of inhibitory receptors may be generally important in systemic peripheral tolerance.

Introduction

It has been well established that intrinsic peripheral tolerance in self-reactive T cells occurs through anergy or deletion. Early work demonstrated that anergy in vitro was because of lack of CD28 costimulation,1 which also led to deletional tolerance in vivo.2,3 However, in other models, CD28 costimulation was required for tolerance induction.4,5 In addition, induction of peripheral deletion and/or anergy in vivo could be reversed by costimulation through CD27, 4-1BB, and OX40.6,7 While these costimulatory pathways operate at distinct points in the response of T cells to foreign antigens, they all induce IL-2 production,8-11 and are associated with up-regulation of antiapoptotic molecules and enhanced survival.10,12-14 However, the basis for their reversal of tolerance induction has not been established.

Inhibitory signals through programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA) receptors, via their ligands programmed cell death-1 ligand 1 (B7-H1; also known as PD-L1) and herpesvirus entry mediator (HVEM), also have been reported to diminish T-cell accumulation and/or acquisition of effector activity in in vitro15 and in vivo16-20 models of tolerance. Interfering with these pathways enables self-reactive T cells to accumulate in secondary lymphoid organs and become fully differentiated effectors that cause autoimmunity.16-19 Inhibitory signals through lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3) also diminish T-cell accumulation in peripheral tissue in vivo,21 but a role for LAG-3 in CD8 T-cell (TCD8) tolerance induction in secondary lymphoid organs has not been established. In response to foreign antigens, signaling via these inhibitory pathways is associated with inhibition of IL-2 production22-24 and diminished expression of antiapoptotic molecules.23 However, it has yet to be clearly established how a lack of costimulation and inhibitory signaling are related to one another during peripheral tolerance induction. Finally, the cells that express the ligands for these inhibitory receptors during peripheral tolerance induction in vivo have yet to be identified.

Peripheral tolerance has classically been ascribed to dendritic cells (DCs) that cross-present self-antigen acquired from peripheral tissues.25 More recently, it has been demonstrated that it can also be mediated via direct presentation by 3 different lymph node (LN) stromal cell (LNSC) populations, including extrathymic Aire-expressing cells,26 fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs),27 and lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs).28 We previously reported that LECs directly present an epitope derived from tyrosinase, a melanocyte differentiation protein that is recognized by TCD8 recovered from melanoma and vitiligo patients, and induce peripheral tolerance through deletion of tyrosinase-specific TCD8.28 Here, we determined the roles of both costimulatory and inhibitory pathways in this process.

Methods

Mice

Thy1.1 C57BL/6 mice carrying the AAD transgene (tyrosinase+) or carrying the AAD transgene with a deletion of tyrosinase (c38R145L; albino) have been described.29 Thy1.2 FH mice expressing a T-cell receptor specific for the Tyr369 epitope in the context of AAD have been described.30 PD-L1−/− mice have been described.20 PD-1−/−20 and Batf3−/−31 mice were from Tusuko Honjo (Kyoto University) and Kenneth Murphy (Washington University), respectively. CD11c:Cre (Aimin Jiang, Yale University) and ROSA26:DTA (R26DTA) mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were intercrossed to generate offspring lacking DCs. Animals were maintained in pathogen-free facilities. Procedures were approved by the University of Virginia Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against CD8a (53-6.7), Thy1.2 (53-2.1), CD45 (30-F11), CD11c (N418), CD31 (390), gp38 (8.1.1), 10.1.1 (in-house), PD-L1 (M1H5), B220 (RA3-6B2, BD), CD11c (N418), PD-L2 (TY25), MHC-II (M5/114.15.2), CD48 (HM4F-1), HVEM (LH1), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), 4-1BBL (TKS-1), OX40L (RM134L), CD70 (FR70), PD-1 (RMP1-30), BTLA (8F4), CD160 (CNX46-3), LAG-3 (C9B7W), 2B4 (244F4), CD25 (PC61.5), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD107a (1D4B), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), or TNF-α (MP6-XT22) were from eBioscience except where noted. Antigen (Ag)–specific cells were identified using Tyr369-HLA-A2 tetramers.30 Samples were run on a FACSCantoII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star).

Macrophage depletion

Mice were injected with control ecapsomes or clodronate liposomes (Encapsula Nanosciences) every 5 days over 2 weeks. Each mouse received 100 μg in the nape of the neck and 50 μg in each flank. Depletion was between 70% and 80%.

Bone marrow chimeras

Tyrosinase+ Thy1.1 and Thy1.2 PD-L1−/− mice were irradiated (650 rad × 2) and reconstituted with 4 × 106 Thy1.1 tyrosinase+ or Thy1.2 PD-L1−/− tyrosinase+ bone marrow cells depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec). More than 85% of peripheral blood Thy1.1 or Thy1.2+ cells were of donor origin 8 weeks after irradiation.

Viruses

Mice were infected with 1 × 106 PFU vaccinia virus expressing tyrosinase (VACV-tyr)30 IP.

Preparation of LN stromal cells

Peripheral LNs were digested with collagenase IV (Worthington) or liberase TM (Roche) and DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) and single-cell suspensions were negatively selected using anti-CD45 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). CD45neg cells were stained with gp38 or 10.1.1 and CD31 antibodies to distinguish stromal subsets.

Adoptive transfer

FH cells were positively selected with anti-CD8α beads (Miltenyi Biotec), labeled with 5-(and-6) carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Invitrogen) or Cell Trace Violet (CTV; Invitrogen) and 1 × 106 were injected intravenously.

In vivo antibody treatment

For molecules expressed by LNSCs, mice were treated every other day starting at day −1 with 200 μg of antibody IP or with isotype control hamster IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) or rat IgG (BioXCell). For inhibitory molecules expressed by T cells, mice were treated on day 0 with 200 μg of antibody IV and at day 1 and every other day with 200 μg of antibody IP. Mice were treated with antibodies against B7-H1/PD-L1 that block interaction with both PD-1 and CD80 (10B5),20,32 PD-1 only (10B4; Park et al32 and L.C., unpublished data, 2012), or CD80 only32 (43H12), or with antibodies against BTLA33 (6A6; BioXcell), LAG-3,21 (C9B7W, eBioscience and in-house) or CD16034 (CNX46-3; eBioscience). For exogenous costimulation, mice were treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB (25 μg, 3H3) and/or anti-OX40 (50 μg, OX86) IP as described.7 For CD25 blockade, mice were treated daily with 200 μg of blocking anti-CD25 (3C7, Biolegend, and in-house). LNs were harvested on day 3 or 7.

Phenotype and ex vivo analysis of T cell function

Single-cell suspensions from LNs were incubated with CD16/32 (2.4G2; BioXCell) to block Fc receptors, with antibodies described in “Antibodies and reagents,” and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde. For intracellular staining, cells were permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences). For ex vivo analysis of T-cell function, FH cells were incubated with AAD+ cells pulsed with 10μM Tyr369 for 5 hours at 37°C in media supplemented with 10 μg/mL monensin (BD Biosciences) and 10 μg/mL brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) containing anti-CD107a antibody, permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences), and stained for intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

LN sections were fixed and blocked with PBS/BSA, 3% H2O2, 0.1% NaN3, and a Biotin-Avidin Blocking kit (Vector Laboratories). Sections were stained with biotinylated PD-L1 and FITC-labeled CD31, gp38, B220, Thy1.2, CD11c, or unlabeled 10.1.1, followed by FITC anti–hamster IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Antibody signals, except for CD31, were amplified using fluorescein and biotin tyramide (PerkinElmer). Images were taken at room temperature using a Nikon Microphot-FXA fluorescent microscope with a Nikon HB-10101AF Mercury Lamp and a Olympus Q color 5 camera and captured using Olympus QCapture Pro Twain software with a plug-in for Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical analysis

P values on paired samples were calculated by unpaired t tests, Mann-Whitney tests, or 1-way analysis of variance with Tukey posttests. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferonni posttests was used to compare multiple groups of samples. Statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism Version 5.0.

Results

LEC induced peripheral tolerance depends selectively on the inhibitory molecule PD-L1

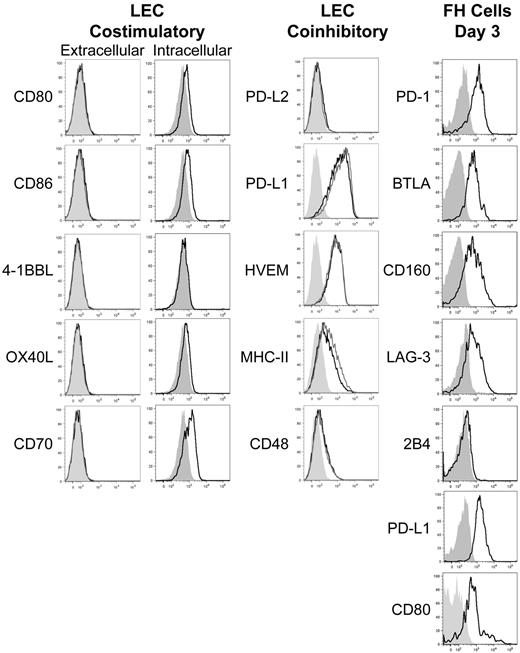

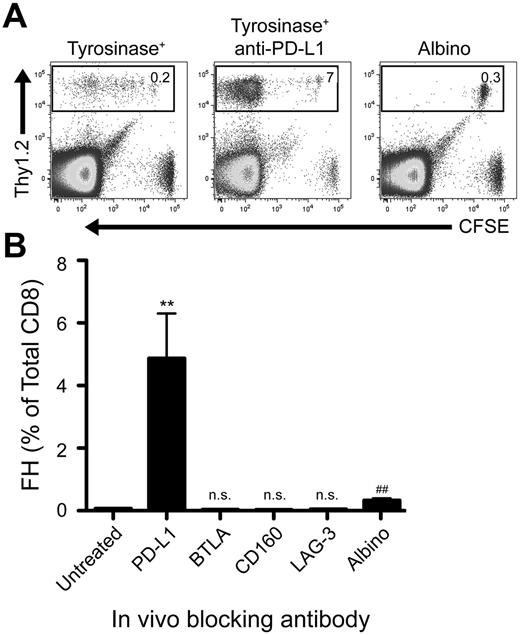

We previously developed T-cell receptor transgenic mice, known as FH, whose TCD8 recognize an MHC-I–restricted epitope from tyrosinase (Tyr369). Adoptive transfer of FH cells into tyrosinase+ recipients leads to their activation in all LNs, but not spleen, based on direct presentation of Tyr369 by LECs.28,30 FH cells activated by LECs fail to accumulate and undergo complete deletion 7 to 14 days after transfer.28,30 In keeping with the possibility that FH cell recognition of Tyr369 in the absence of costimulation leads to peripheral tolerance, LECs do not express the costimulatory ligands CD80, 4-1BBL, and OX40L extracellularly or intracellularly (Figure 1). Although LECs express CD86 and CD70 intracellularly, surface expression was negligible (Figure 1). In keeping with the possibility that FH cells undergo deletion due to recognition of Tyr369 in the context of an inhibitory pathway, LECs do not express programmed cell death-1 ligand 2 (PD-L2), Fas ligand, or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), but display high levels of PD-L1, HVEM, MHC-II, and CD48 (Figure 1 and not depicted). In mice adoptively transferred with FH cells 3 days previously, PD-L1 and MHC-II expression was slightly increased on LECs, while expression of other costimulatory and inhibitory molecules was unchanged (Figure 1). Three days after adoptive transfer into tyrosinase+ mice, FH cells express PD-1, BTLA, CD160, and LAG-3 (receptors for PD-L1, HVEM, and MHC-II, respectively), but not the CD48 receptor 2B4 (Figure 1). Thus, LECs could induce deletional tolerance through either a lack of costimulation, provision of inhibitory signals, or both. To determine the relevance of the inhibitory molecules, FH cells were adoptively transferred into tyrosinase+ mice treated with blocking antibodies. Blockade of PD-L1 led to robust accumulation in tyrosinase+ recipients (Figure 2), but not albino recipients (not depicted), while blockade of LAG-3, BTLA, and CD160 had no effect. Thus, despite the potential involvement of multiple inhibitory pathways, LEC-mediated deletion of FH cells is solely dependent on PD-L1.

LECs fail to express costimulatory ligands but express numerous inhibitory ligands while activated FH cells express the pertinent inhibitory receptors. gp38+CD31+ LECs were stained intracellularly or extracellularly for the expression of the costimulatory ligands CD80, CD86, 4-1BBL, OX40L, and CD70 and extracellularly for the inhibitory ligands PD-L2, PD-L1, HVEM, MHC-II, and CD48 under steady-state conditions or 3 days after transfer of FH cells. FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ recipients and examined 3 days after transfer for the expression of the inhibitory receptors PD-1, BTLA, CD160, LAG-3, 2B4, PD-L1, and CD80. Shading indicates fluorescence minus one (FMO), solid black line indicates expression by LECs in the steady-state or FH cells, and solid gray line indicates extracellular expression by LECs following FH adoptive transfer. LEC data are representative of at least 2 to 3 independent experiments, using LN pooled from multiple mice, with a single replicate for each sample. FH cell data are representative of 4 independent experiments using LN pooled from individual mice.

LECs fail to express costimulatory ligands but express numerous inhibitory ligands while activated FH cells express the pertinent inhibitory receptors. gp38+CD31+ LECs were stained intracellularly or extracellularly for the expression of the costimulatory ligands CD80, CD86, 4-1BBL, OX40L, and CD70 and extracellularly for the inhibitory ligands PD-L2, PD-L1, HVEM, MHC-II, and CD48 under steady-state conditions or 3 days after transfer of FH cells. FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ recipients and examined 3 days after transfer for the expression of the inhibitory receptors PD-1, BTLA, CD160, LAG-3, 2B4, PD-L1, and CD80. Shading indicates fluorescence minus one (FMO), solid black line indicates expression by LECs in the steady-state or FH cells, and solid gray line indicates extracellular expression by LECs following FH adoptive transfer. LEC data are representative of at least 2 to 3 independent experiments, using LN pooled from multiple mice, with a single replicate for each sample. FH cell data are representative of 4 independent experiments using LN pooled from individual mice.

Blockade of PD-L1, but not other inhibitory molecules, rescues FH cells from deletion. (A) Representative and (B) cumulative data of Thy1.2 FH cells transferred into Thy1.1 tyrosinase+ mice, tyrosinase+ mice treated with blocking antibodies against inhibitory ligands, or antigen-free albino mice. LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer. (A) Boxes represent the percentage of TCD8 that are Thy1.2+ FH cells in the LNs of recipient mice. Data represent 4 to 8 mice per condition from 2 to 8 independent experiments. (B) **P = .0049, ##P = .0021 (2-tailed, unpaired t test; error bars, SEM).

Blockade of PD-L1, but not other inhibitory molecules, rescues FH cells from deletion. (A) Representative and (B) cumulative data of Thy1.2 FH cells transferred into Thy1.1 tyrosinase+ mice, tyrosinase+ mice treated with blocking antibodies against inhibitory ligands, or antigen-free albino mice. LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer. (A) Boxes represent the percentage of TCD8 that are Thy1.2+ FH cells in the LNs of recipient mice. Data represent 4 to 8 mice per condition from 2 to 8 independent experiments. (B) **P = .0049, ##P = .0021 (2-tailed, unpaired t test; error bars, SEM).

PD-L1 expressed on LECs mediates FH cell deletion

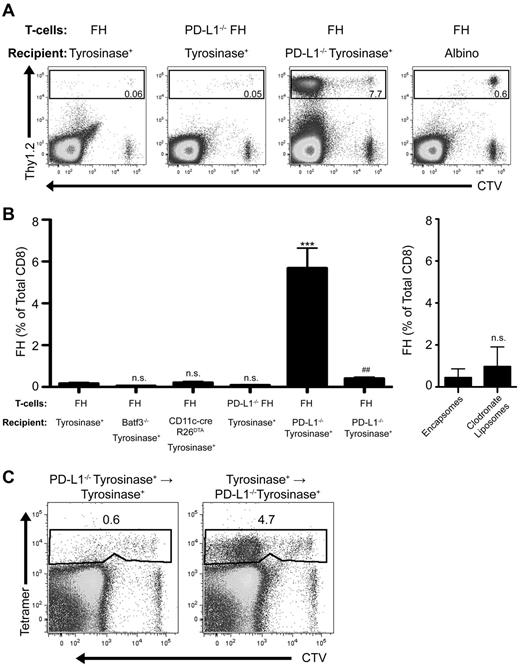

PD-L1 is widely expressed on nonhematopoietic and hematopoetic cells, including activated FH cells (Figure 1). However, PD-L1−/− FH cells did not accumulate after transfer into tyrosinase+ recipients (Figure 3A-B). Conversely, FH cells transferred into tyrosinase+ PD-L1−/− recipients accumulated robustly. FH cells also underwent deletion in recipients treated with clodronate liposomes to deplete macrophages, and in Batf3−/− and CD11c-cre+ × R26DTA mice (Figure 3B). Thus, expression of PD-L1 on macrophages and DCs, including radioresistant subpopulations such as Langerhans cells, does not contribute to FH cell tolerance induction. To determine whether the relevant PD-L1–expressing cell was hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic, we used reciprocal bone marrow chimeras. FH cells still underwent deletion after transfer into mice that expressed PD-L1 only on radioresistant nonhematopoietic cells, but accumulated in mice that expressed PD-L1 only on radiosensitive hematopoietic cells (Figure 3C). Thus, PD-L1+ radioresistant nonhematopoietic cells are entirely responsible for LEC-induced deletion.

PD-L1 expressed by a nonhematopoietic radioresistant, and not radiosensitive, cell is responsible for LEC-mediated FH cell deletion. (A) Representative and (B) cumulative data of FH or PD-L1−/− FH cells transferred into tyrosinase+, Batf3−/− tyrosinase+, CD11c-cre+R26DTA tyrosinase+, PD-L1−/− tyrosinase+, tyrosinase+ treated with control encapsomes or clodronate liposomes, or albino recipients. ***P = .0001, ##P = .0059 (2-tailed, unpaired t test; error bars, SEM). (C) Representative data of FH cells transferred into recipient bone marrow chimeras lacking PD-L1 expression in either the hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic compartment. (A-C) LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer. Boxes represent the percentage of TCD8 that are FH or PD-L1−/− FH cells in the LN of recipient mice. Data represent 2 to 10 mice per condition from 1 to 7 independent experiments.

PD-L1 expressed by a nonhematopoietic radioresistant, and not radiosensitive, cell is responsible for LEC-mediated FH cell deletion. (A) Representative and (B) cumulative data of FH or PD-L1−/− FH cells transferred into tyrosinase+, Batf3−/− tyrosinase+, CD11c-cre+R26DTA tyrosinase+, PD-L1−/− tyrosinase+, tyrosinase+ treated with control encapsomes or clodronate liposomes, or albino recipients. ***P = .0001, ##P = .0059 (2-tailed, unpaired t test; error bars, SEM). (C) Representative data of FH cells transferred into recipient bone marrow chimeras lacking PD-L1 expression in either the hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic compartment. (A-C) LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer. Boxes represent the percentage of TCD8 that are FH or PD-L1−/− FH cells in the LN of recipient mice. Data represent 2 to 10 mice per condition from 1 to 7 independent experiments.

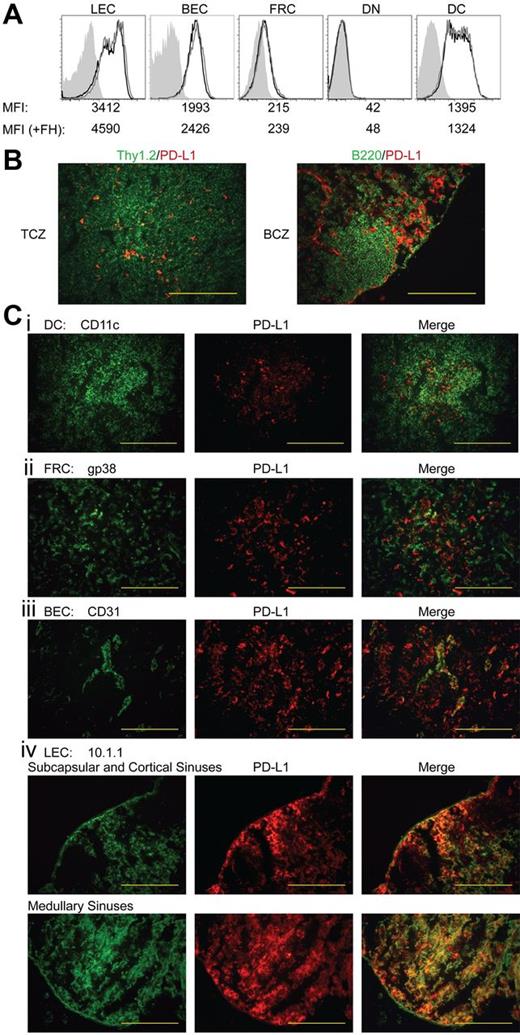

Because LEC-induced deletion of FH cells occurs only in LNs,30 we evaluated the level and distribution of PD-L1 on radioresistant LNSC populations. By flow cytometry, LECs expressed the highest level of PD-L1, although distinct subpopulations expressed intermediate and high levels (Figure 4A). PD-L1 expression on blood endothelial cells (BECs) was comparable with that of the intermediate LECs. However, FRCs expressed only approximately 5% as much PD-L1 as LECs, while double-negative cells were PD-L1 negative. Although not involved in FH cell deletion, subsets of DCs expressed low and intermediate levels of PD-L1. Adoptive transfer of FH cells led to a slight increase in PD-L1 expression by LECs and BECs, but PD-L1 expression on FRCs, double-negative cells, and DCs remained unchanged (Figure 4A). By immunofluorescent microscopy of LNs, we found sparse, punctate PD-L1 expression throughout the T-cell zone and more continuously in areas peripheral to B-cell follicles (Figure 4B). However, PD-L1 did not costain B220+ cells in the follicles, and within the T-cell zone, only rarely costained Thy1.2+, gp38+, or CD11c+ cells (Figure 4B-C). Much of the PD-L1 staining in the T-cell zone was colocalized with CD31+ BECs making up high endothelial venules (Figure 4C). However, using the LEC-specific marker 10.1.1, we found contiguous PD-L1 expression in subcapsular, cortical, and medullary lymphatic sinuses (Figure 4C). Although LECs in all sinuses were strongly PD-L1+, 2.5- to 3-fold longer exposure times of cortical sinus sections were necessary to give photographic intensities equivalent to those of medullary LEC sections. This suggests that the PD-L1int LEC population evident by flow cytometry resides in the cortical sinuses while the PD-L1hi LEC population resides in the medullary sinus. Based on this prevalent high-level expression of PD-L1, as well as the expression of tyrosinase, we conclude that PD-L1 expressed by radioresistant LECs is responsible for FH cell deletional tolerance.

Among LN populations, PD-L1 is most highly expressed on LECs. (A) Representative data of PD-L1 expression among LN populations. LN suspensions were separated based on CD45 expression. CD45neggp38+CD31+ LECs, CD45neggp38negCD31+ BECs, CD45neggp38+CD31neg FRCs, CD45neggp38negCD31neg double-negative cells, and CD45+CD3negCD11c+ DCs were stained for their expression of PD-L1. Shading indicates FMO, solid black line indicates steady-state PD-L1 expression, and solid gray line represents PD-L1 expression 3 days post-FH cell adoptive transfer. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each independent sample is listed below the appropriate panel. Data are representative of 2 to 6 independent experiments, using LN pooled from multiple mice, with a single replicate for each sample. (B) LN sections were stained with PD-L1 along with Thy1.2 to distinguish T cells and the T-cell zone and B220 to distinguish B cells and the B-cell zone or (Ci) CD11c, (ii) gp38, (iii) CD31, and (iv) 10.1.1 to distinguish DCs, FRCs, BECs, and LECs, respectively. Red staining demonstrates where PD-L1 is expressed within the LNs while green is used to determine cell-specific markers. Staining is representative of multiple magnifications and fields from 2 independent experiments consisting of multiple LNs per mouse. (magnification of ×200; B-C). Bars = 200 μm.

Among LN populations, PD-L1 is most highly expressed on LECs. (A) Representative data of PD-L1 expression among LN populations. LN suspensions were separated based on CD45 expression. CD45neggp38+CD31+ LECs, CD45neggp38negCD31+ BECs, CD45neggp38+CD31neg FRCs, CD45neggp38negCD31neg double-negative cells, and CD45+CD3negCD11c+ DCs were stained for their expression of PD-L1. Shading indicates FMO, solid black line indicates steady-state PD-L1 expression, and solid gray line represents PD-L1 expression 3 days post-FH cell adoptive transfer. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of each independent sample is listed below the appropriate panel. Data are representative of 2 to 6 independent experiments, using LN pooled from multiple mice, with a single replicate for each sample. (B) LN sections were stained with PD-L1 along with Thy1.2 to distinguish T cells and the T-cell zone and B220 to distinguish B cells and the B-cell zone or (Ci) CD11c, (ii) gp38, (iii) CD31, and (iv) 10.1.1 to distinguish DCs, FRCs, BECs, and LECs, respectively. Red staining demonstrates where PD-L1 is expressed within the LNs while green is used to determine cell-specific markers. Staining is representative of multiple magnifications and fields from 2 independent experiments consisting of multiple LNs per mouse. (magnification of ×200; B-C). Bars = 200 μm.

LEC-induced deletion results from lack of costimulation that leads to rapid and elevated PD-1 expression

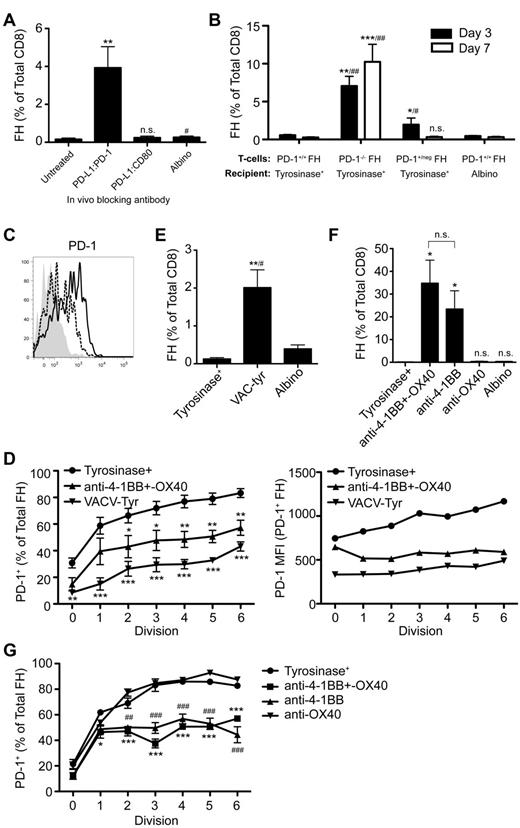

PD-L1 can deliver inhibitory signals leading to peripheral tolerance through PD-1 or CD80.16,17,20,32 In addition to PD-1, CD80 was also up-regulated on FH cells transferred into tyrosinase+ mice (Figure 1). However, using anti-PD-L1 antibodies that selectively block interaction with PD-1 or CD80, only interference with the PD-L1:PD-1 pathway led to FH cell accumulation (Figure 5A). This was confirmed using antibodies against PD-1 or CD80 that block interaction with PD-L1 (not depicted). Finally, PD-1−/− FH cells transferred into tyrosinase+ recipients underwent robust accumulation (Figure 5B). Thus, LEC-induced deletion is based on PD-L1 engagement of PD-1 and not CD80.

PD-L1 engages PD-1, which is expressed more rapidly and at a higher level following presentation of tyrosinase by LECs because of deficient costimulation, leading to FH cell deletion. (A) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ recipients treated with antibodies against PD-L1 that block interactions with PD-1 or CD80 and LNs harvested 7 days after transfer. Data represent 5 to 8 mice per condition from 5 to 6 independent experiments, respectively. **P = .0011, #P = .0262 (2-tailed, unpaired t test). (B) PD-1+/+, PD-1+/neg, or PD-1−/− FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ or albino recipients and LN harvested 3 or 7 days after transfer. Data represent 5 to 7 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments for day 3. Day 7 data represents 8 to 9 mice per condition from 3 to 5 independent experiments (*compared with tyrosinase+, #compared with albino). Day 3: *P = .0222, **P = .0057, #P = .0381, ##P = .0061. Day 7: ***P = .0006, ##P = .0028 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney test). (C) PD-1 expression was determined on naive (shaded) and CD69+ FH cells 24 hours after transfer into tyrosinase+ recipients (solid black line) or into albino recipients infected with VACV-tyr (dashed line). Data are representative of mice from 2 independent experiments. (D) Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express PD-1 and their level of PD-1 expression by MFI 3 days after transfer. Data are from 5 to 8 independent experiments using tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴), and albino mice infected with VACV-Tyr (▾). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). (E) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice, albino mice infected with VACV-tyr, or antigen-free albino mice. LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer and the percentage of FH cells determined. Data represent 4 to 6 mice per condition from 5 independent experiments (*compared with tyrosinase+, #compared with albino); **P = .0056, #P = .0259 (2-tailed, unpaired t test). (F) Tyrosinase+ recipients were left untreated or treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40, anti-4-1BB only, or anti-OX40 only. Cumulative data represents 3 to 7 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments. *P = .0167 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney test). (G) Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express PD-1 3 days posttransfer. Data are from one experiment using 3 untreated tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (■), agonist anti-4-1BB only (▴), or agonist anti-OX40 only (▾). #,*P < .05; ##,**P < .01; ###,***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). Error bars (A,B,D-G), SEM.

PD-L1 engages PD-1, which is expressed more rapidly and at a higher level following presentation of tyrosinase by LECs because of deficient costimulation, leading to FH cell deletion. (A) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ recipients treated with antibodies against PD-L1 that block interactions with PD-1 or CD80 and LNs harvested 7 days after transfer. Data represent 5 to 8 mice per condition from 5 to 6 independent experiments, respectively. **P = .0011, #P = .0262 (2-tailed, unpaired t test). (B) PD-1+/+, PD-1+/neg, or PD-1−/− FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ or albino recipients and LN harvested 3 or 7 days after transfer. Data represent 5 to 7 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments for day 3. Day 7 data represents 8 to 9 mice per condition from 3 to 5 independent experiments (*compared with tyrosinase+, #compared with albino). Day 3: *P = .0222, **P = .0057, #P = .0381, ##P = .0061. Day 7: ***P = .0006, ##P = .0028 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney test). (C) PD-1 expression was determined on naive (shaded) and CD69+ FH cells 24 hours after transfer into tyrosinase+ recipients (solid black line) or into albino recipients infected with VACV-tyr (dashed line). Data are representative of mice from 2 independent experiments. (D) Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express PD-1 and their level of PD-1 expression by MFI 3 days after transfer. Data are from 5 to 8 independent experiments using tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴), and albino mice infected with VACV-Tyr (▾). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). (E) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice, albino mice infected with VACV-tyr, or antigen-free albino mice. LNs were harvested 7 days postadoptive transfer and the percentage of FH cells determined. Data represent 4 to 6 mice per condition from 5 independent experiments (*compared with tyrosinase+, #compared with albino); **P = .0056, #P = .0259 (2-tailed, unpaired t test). (F) Tyrosinase+ recipients were left untreated or treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40, anti-4-1BB only, or anti-OX40 only. Cumulative data represents 3 to 7 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments. *P = .0167 (nonparametric Mann-Whitney test). (G) Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express PD-1 3 days posttransfer. Data are from one experiment using 3 untreated tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (■), agonist anti-4-1BB only (▴), or agonist anti-OX40 only (▾). #,*P < .05; ##,**P < .01; ###,***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). Error bars (A,B,D-G), SEM.

Signaling through PD-1 can lead to deletion, anergy, and exhaustion.16,17,20,35 However, PD-1 is also expressed on T cells activated by immunogenic stimulation.35 To determine how PD-1 expression leads to different outcomes, we compared FH cells activated by either LECs or an immunogenic stimulus. Approximately 40% of activated (CD69+) FH cells up-regulated PD-1 within 24 hours after LEC encounter and before their first division (Figure 5C). In contrast, less than 15% of CD69+ FH cells transferred into albino recipients infected with VACV-tyr had up-regulated PD-1 at this same point. Three days after Ag encounter, the percentage of FH cells activated by LECs that were PD-1+ was significantly higher than that of VACV-tyr–activated FH cells that had undergone a comparable number of divisions (Figure 5D left panel). The level of expression was also substantially higher on PD-1+ FH cells that had been activated by LECs, and in contrast to that of VACV-tyr–activated cells, increased with each cell division (Figure 5D right panel). Indeed, VACV-tyr–activated FH cells that had undergone 6 divisions still expressed less PD-1 in absolute and percentage terms than LEC-activated FH cells that had divided only once. Furthermore, FH cells activated following VACV-tyr infection accumulated despite the expression of PD-1 (Figure 5E). This suggested that the level of PD-1 expression might determine whether proliferating T cells accumulated or deleted. In support of this, PD-1+/neg heterozygous FH cells expressing half as much PD-1 (not depicted) actually accumulated 3 days after transfer compared with FH cells transferred into an albino recipient (Figure 5B). By day 7, however, PD-1+/neg and PD-1+/+ FH cells had deleted to a comparable extent. Thus, presentation of antigen by LECs leads to more rapid and higher level PD-1 expression that predisposes TCD8 to undergo deletion rather than accumulation.

An important difference between LECs and professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the context of vaccinia infection is their expression of costimulatory molecule ligands. To determine whether rapid, high-level expression of PD-1 on FH cells was because of lack of costimulation by LECs, we used agonistic antibodies specific for 4-1BB and OX40. Administration of anti-4-1BB and –OX40 24 hours after transfer into tyrosinase+ mice suppressed the rapid, high-level expression of PD-1 induced by LECs (Figure 5D) and led to substantial FH cell accumulation (Figure 5F). These effects were recapitulated by anti-4-1BB alone, while anti-OX40 was without significant effect either alone or in combination (Figure 5F-G). We attribute this to the timing of the expression of 4-1BB and OX40 on FH cells activated by LECs. FH cells activated by tyrosinase+ LECs up-regulated 4-1BB within 24 hours while OX40 was not detected until 72 hours (not depicted). These results indicate that the lack of costimulation by LECs, and potentially other nonprofessional APCs, is responsible for the rapid, high-level expression of PD-1 on TCD8 that predisposes them for deletion.

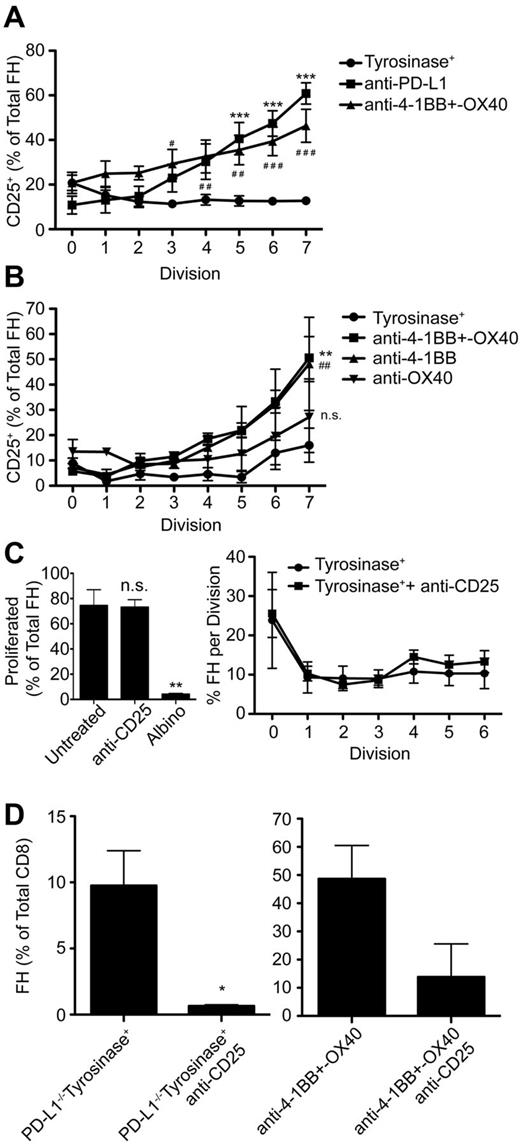

Signaling through PD-1 is associated with numerous downstream effects that inhibit TCD8 activation and function, but is complex and poorly understood. PD-1 signaling blocks T-cell receptor signaling in vitro36 and is associated with inhibition of numerous pathways necessary for T-cell activation, proliferation, and differentiation into effectors.15,23,36-38 However, the mechanisms by which PD-1 signaling leads to TCD8 peripheral deletion in vivo remain poorly understood. FH cells undergoing deletion after LEC encounter expressed less Bcl-xL and more Bim compared with naive cells and high levels of several additional proapoptotic molecules. However, these patterns were reversed in FH cells rescued via PD-L1 blockade or exogenous costimulation with anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). It has been previously reported that PD-1 signaling blocks autocrine IL-2 production, and that IL-2 overcomes PD-1–mediated inhibition of TCD8 proliferation in vitro37 and anergy in vivo.39 However, FH cells still underwent deletion in tyrosinase+ mice given IL-2 (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Instead, FH cells expressed high levels of the CD122 chain of the IL-2 receptor (IL-2R; supplemental Figure 2C), but did not up-regulate the CD25 chain 3 days after adoptive transfer (Figure 6A). In contrast, FH cells rescued through PD-L1 blockade, anti-4-1BB and –OX40 costimulation, or anti-4-1BB costimulation alone, expressed equivalent levels of CD122 but significantly up-regulated CD25 (Figure 6A-B, supplemental Figure 2C). This indicates that PD-1 signaling in TCD8 undergoing deletion is inherently different from in anergic TCD8.

Signaling through the high-affinity IL-2R, whose expression is inhibited by PD-L1:PD-1 engagement, is required for FH cell survival, but not proliferation. (A-B) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice treated with (A) blocking anti-PD-L1 (■), agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴), or left untreated (•) and (B) tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (■), anti-4-1BB only (▴), or anti-OX40 only (▾). CD25 expression on proliferating FH cells was examined 3 days later. Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express CD25 3 days after transfer. (A) Data represents 4 to 9 mice per condition from 4 to 9 independent experiments (*anti-PD-L1, #anti-4-1BB and –OX40) (B) Data represent 3 mice per condition (*anti-4-1BB + –OX40, #anti-4-1BB). #, *, P < .05; # #, **, P < .01; # # #, ***, P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). (C) Tyrosinase+ mice that had been adoptively transferred with CTV-labeled FH cells were left untreated (•) or treated with blocking anti-CD25 (■) beginning on day 0 and every 24 hours thereafter. Proliferation was evaluated 3 days posttransfer by flow cytometry. Data represent 3 to 6 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments. **P = .0052. (D) PD-L1−/− recipients and recipients treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 were treated with anti-CD25 beginning on day 0 and every 24 hours thereafter. LNs were harvested 7 days later and the percentage of FH cells of total TCD8 cells was determined. Data represent 3 untreated and 3 treated PD-L1−/− mice from one experiment and 6 mice treated with anti-4-1BB+–OX40 and 2 mice treated additionally with anti-CD25 from 2 independent experiments (C-D: 2-tailed, unpaired t test). Error bars (A-D), SEM.

Signaling through the high-affinity IL-2R, whose expression is inhibited by PD-L1:PD-1 engagement, is required for FH cell survival, but not proliferation. (A-B) FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice treated with (A) blocking anti-PD-L1 (■), agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴), or left untreated (•) and (B) tyrosinase+ mice (•), tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (■), anti-4-1BB only (▴), or anti-OX40 only (▾). CD25 expression on proliferating FH cells was examined 3 days later. Data represent the percentage of FH cells that have undergone the indicated number of divisions that express CD25 3 days after transfer. (A) Data represents 4 to 9 mice per condition from 4 to 9 independent experiments (*anti-PD-L1, #anti-4-1BB and –OX40) (B) Data represent 3 mice per condition (*anti-4-1BB + –OX40, #anti-4-1BB). #, *, P < .05; # #, **, P < .01; # # #, ***, P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). (C) Tyrosinase+ mice that had been adoptively transferred with CTV-labeled FH cells were left untreated (•) or treated with blocking anti-CD25 (■) beginning on day 0 and every 24 hours thereafter. Proliferation was evaluated 3 days posttransfer by flow cytometry. Data represent 3 to 6 mice per condition from 3 independent experiments. **P = .0052. (D) PD-L1−/− recipients and recipients treated with agonistic anti-4-1BB and –OX40 were treated with anti-CD25 beginning on day 0 and every 24 hours thereafter. LNs were harvested 7 days later and the percentage of FH cells of total TCD8 cells was determined. Data represent 3 untreated and 3 treated PD-L1−/− mice from one experiment and 6 mice treated with anti-4-1BB+–OX40 and 2 mice treated additionally with anti-CD25 from 2 independent experiments (C-D: 2-tailed, unpaired t test). Error bars (A-D), SEM.

To test the hypothesis that up-regulation of CD25 was required for FH cell survival after interaction with Tyr369-presenting LECs, PD-L1−/− recipients and wild-type recipients treated with anti-4-1BB and –OX40 were injected with blocking antibodies against CD25. In keeping with other work,40 this blockade did not suppress the initial induction of FH cell proliferation (Figure 6C). However, CD25 blockade completely abrogated FH cell rescue in PD-L1−/− mice and dramatically reduced it in mice treated with anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (Figure 6D). Thus, diminished FH cell survival as a consequence of LEC encounter occurs in part through PD-1–mediated inhibition of high-affinity IL-2R expression.

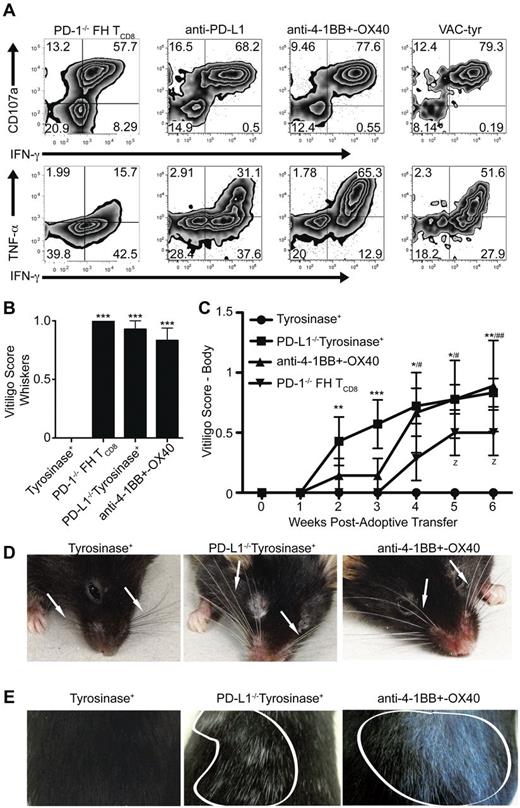

Bypassing LEC-mediated tolerance leads to autoimmunity

As tolerance mediated by LECs has only recently been demonstrated, the consequences of bypassing it remain to be elucidated. In addition, it is unknown whether LECs can function as APCs and induce fully differentiated effector TCD8 capable of mounting an immune response. FH cells rescued from LEC-mediated deletion through PD-1 deficiency, blockade of PD-L1, or costimulation with anti-4-1BB and –OX40 expressed high levels of CD107a, a measure of cytolytic function, and produced IFN-γ and TNF-α (Figure 7A). To determine whether bypassing LEC-mediated deletion leads to autoimmunity, FH, or PD-1−/− FH cells were transferred into untreated tyrosinase+ mice, PD-L1−/− mice, or mice treated with anti-4-1BB and –OX40. Mice were examined weekly for the development of autoimmune vitiligo based on the destruction of tyrosinase+ melanocytes.29 While untreated wild-type tyrosinase+ mice remained normally pigmented, recipients of PD-1−/− FH cells, PD-L1−/− mice, and those treated with agonistic costimulatory antibodies developed vitiligo (Figure 7B-E). Vitiligo development did not occur in mice that had not been given FH cells (not depicted). Whiskers at the muzzle and above the eyes became depigmented (Figure 7B,D, Table 1). Coat depigmentation was evident as early as 2 weeks posttransfer and continued to progress through 7 weeks (Figure 7C,E, Table 1). Thus, under conditions where inhibitory signaling is blocked or costimulatory signaling is enhanced, LECs have the ability to activate TCD8 cells to become fully differentiated effectors capable of causing autoimmune disease.

Bypassing LEC-mediated tolerance enables FH cells to acquire cytolytic and effector function leading to the development of autoimmune vitiligo. (A) FH or PD-1−/− FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice left untreated or treated with blocking anti-PD-L1, or agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40. Albino mice were infected with VACV-tyr. LNs were harvested 7 days after transfer and restimulated ex vivo. Numbers indicate the total percentages of FH cells that are negative, single, or double positive for CD107a, IFN-γ, or TNF-α. Data are representative of 4 to 11 mice per condition from 2 to 5 independent experiments. (B-E) FH or PD-1−/− (▾) FH cells were transferred into untreated tyrosinase+ mice (•), PD-L1−/− mice (■), or tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴). Mice were monitored weekly for the development of autoimmune vitiligo evidenced by (B,D) whisker or (C,E) coat depigmentation. Arrows point to whiskers (C) and areas of coat depigmention are outlined in white (D). (B,D) Data for vitligo scoring of whiskers is representative of 3 to 7 mice per condition from 2 independent experiment while (C,E) data for vitiligo scoring of the body is representative of 7 to 9 mice per condition from 2 to 3 independent experiments. (B) ***P < .005 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey posttest). (C) * indicates PD-L1−/−tyrosinase+; #, anti-4-1BB and OX40 treated; z, PD-1−/− FH TCD8. z, #, *P < .05; ##, **P < .01, ***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). Error bars (B-C), SEM.

Bypassing LEC-mediated tolerance enables FH cells to acquire cytolytic and effector function leading to the development of autoimmune vitiligo. (A) FH or PD-1−/− FH cells were transferred into tyrosinase+ mice left untreated or treated with blocking anti-PD-L1, or agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40. Albino mice were infected with VACV-tyr. LNs were harvested 7 days after transfer and restimulated ex vivo. Numbers indicate the total percentages of FH cells that are negative, single, or double positive for CD107a, IFN-γ, or TNF-α. Data are representative of 4 to 11 mice per condition from 2 to 5 independent experiments. (B-E) FH or PD-1−/− (▾) FH cells were transferred into untreated tyrosinase+ mice (•), PD-L1−/− mice (■), or tyrosinase+ mice treated with agonist anti-4-1BB and –OX40 (▴). Mice were monitored weekly for the development of autoimmune vitiligo evidenced by (B,D) whisker or (C,E) coat depigmentation. Arrows point to whiskers (C) and areas of coat depigmention are outlined in white (D). (B,D) Data for vitligo scoring of whiskers is representative of 3 to 7 mice per condition from 2 independent experiment while (C,E) data for vitiligo scoring of the body is representative of 7 to 9 mice per condition from 2 to 3 independent experiments. (B) ***P < .005 (one-way ANOVA, Tukey posttest). (C) * indicates PD-L1−/−tyrosinase+; #, anti-4-1BB and OX40 treated; z, PD-1−/− FH TCD8. z, #, *P < .05; ##, **P < .01, ***P < .005 (2-way ANOVA, Bonferonni posttest). Error bars (B-C), SEM.

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that LECs directly present an epitope from the melanocyte differentiation protein tyrosinase, and induce complete deletion of tyrosinase-specific TCD8.28,30 In the present study, we established that LECs act via PD-L1:PD-1, despite also expressing ligands for the CD160, BTLA, and LAG-3 inhibitory pathways. Although LECs can induce initial activation and proliferation, their failure to express costimulatory molecules, particularly 4-1BBL, leads to rapid, high-level expression of PD-1 on TCD8. This in turn blocks up-regulation of the high-affinity IL-2R, which is necessary for survival, culminating in apoptotic death. Rescue of tyrosinase-specific TCD8 either by interference with PD-1 signaling or provision of costimulatory signals leads to the induction of autoimmune vitiligo, demonstrating that LECs are significant, albeit suboptimal, APCs. Based on the fact that LECs express numerous peripheral tissue antigens,27,28 lack of costimulation coupled to rapid, high-level up-regulation of inhibitory receptors may be of general importance in the development of systemic peripheral tolerance.

PD-L1 was demonstrated previously to have a role in peripheral tolerance induction following both direct- and cross-presentation of self-antigen within LNs,16-18 but the PD-L1+ cell responsible was not identified. We demonstrate here that radiosensitive PD-L1+ cells play no role in the induction of tolerance to tyrosinase, and that it is mediated entirely by a radioresistant, nonhematopoietic, PD-L1+ cell. We conclude these cells are LECs based on the fact that they are radioresistant, express tyrosinase, and also consistently express the highest levels of PD-L1 of any cell in the LN. Our results do not formally exclude a role for BECs, which are also radioresistant, but consistently express a lower level of PD-L1. However, FH cells would most likely engage BECs as they enter the LNs through high endothelial venules, at which point they would be naive and PD-1neg. A small number of FH cells could leave the LN following activation by LECs and engage PD-L1+ BECs on re-entry into a different LN, but this is likely not a major mechanism. Similarly, the low level of PD-L1 expression on FRCs, coupled with our observations about the influence of PD-1 levels on TCD8 deletion, suggests that they will be ineffective inducers of FH cell deletion. Our data suggest a model in which FH cells activated by costimulatory molecule-deficient LECs rapidly up-regulate PD-1, and continuously engage PD-L1+ LECs as they attempt to exit the LN.

Our results raise provocative questions about the identity of the PD-L1+ cells that are involved in tolerance when the antigen is presented by DCs or FRCs. While PD-L1 is involved in peripheral cross-tolerance,18,21 it has not been directly demonstrated that this is because of PD-L1 expressed on DCs. We show that PD-L1 expression is high on DCs as evaluated by flow cytometry, but seems to be largely occluded in the LN microenvironment and it is not clear whether it is functionally relevant in vivo. In iFABP-OVA transgenic mice, both FRCs and DCs present self-antigen,41 and tolerance is PD-L1 dependent.27 In addition, FRCs express very low levels of PD-L1, which may be insufficient to induce tolerance directly. The finding that PD-L1 is most highly expressed on LECs in an unperturbed naive LN suggests an alternative model in which TCD8 activated through direct-presentation by FRCs or cross-presentation by DCs might then engage PD-L1 on LECs as they exit the LNs.

Our results demonstrate, perhaps unexpectedly, that despite the potential engagement of the BTLA:HVEM, CD160:HVEM, and LAG-3:MHC-II inhibitory pathways, other inhibitory pathways do not compensate to enforce peripheral tolerance mediated by LECs when the PD-L1:PD-1 pathway is compromised. This is in contrast to the additive role of these pathways in effector TCD8, which progressively lose their ability to proliferate and produce inflammatory cytokines as the expression of different inhibitory receptors is increased.34 It has not been determined whether inhibitory pathways other than PD-L1:PD-1 are involved in peripheral tolerance induction by FRCs in the LN of iFABP-OVA mice. Both LAG-3 and PD-1 have been reported to play important roles in the prevention of autoimmune disease in C3-HA mice.16,21 However, while LAG-3 blockade was shown to increase the accumulation and effector function of effector TCD8 in peripheral tissue,21 its involvement in peripheral tolerance induction in LNs was not evaluated. More directly, cross-tolerance in LNs of RIP-mOVA mice depends on both BTLA and PD-1.18,19 However, BTLA signaling was not shown to induce TCD8 deletion.19 Instead, inhibition of BTLA signaling enhanced the proliferation of OT-I cells and the incidence of OT-I–dependent autoimmune disease.19 In a strict deletional model, it would be expected that enhanced proliferation would have led to more rapid deletion. However, a portion of OT-I cells in RIP-mOVA mice persist to at least day 14,19 suggesting that they can also become anergic. This is consistent with a model in which BTLA signaling induces anergy while PD-1 signaling induces deletion. It would also be expected that the induction of anergy by BTLA would only be evident in TCD8 that do not express PD-1. Recently, it has been shown that LECs limit the proliferation of already activated T cells,42,43 and that this can be mediated by LEC release of nitric oxide (NO) in response to IFN-γ, TNF-α, and T-cell contact.43 However, FH cells undergoing LEC-mediated deletion proliferate robustly, but produce little to no IFN-γ or TNF-α (E.F.T. and V.H.E., unpublished data, 2012). Thus, NO is unlikely to participate in LEC-mediated deletional tolerance.

Several previous studies have demonstrated that either costimulation1,6,7 or blockade of inhibitory pathways16-20 can rescue TCD8 from anergy or deletion associated with peripheral tolerance, but the relationship between the two has not been previously examined. Costimulation through CD27 has been correlated with decreased PD-1 expression on tumor-infiltrating effector TCD8.44 However, this was not a model of peripheral tolerance, and because CD27 is expressed on all naive T cells, it is unclear whether costimulation directly inhibited PD-1 expression on TCD8, or operated indirectly by changing the quality or availability of help. More directly, lack of costimulation of naive TCD8 in vitro led to anergy associated with elevated PD-1 expression, and blockade of PD-1 restored functional activity.15 However, the outcome of T-cell activation was interpreted as dependent on a variable level of costimulation balanced against a constitutive level of inhibitory signaling. Here, we demonstrated conclusively that costimulatory and inhibitory pathways are interdependent, and that costimulation through 4-1BB specifically blocks the expression of PD-1 on TCD8 that is responsible for deletional tolerance. In this model, BTLA, CD160, and LAG-3 were also expressed on TCD8, but the level of expression of BTLA and CD160 was not changed by the provision of costimulatory signals. LAG-3 expression was decreased on TCD8 rescued by either PD-L1 blockade or costimulation and was thus not specifically regulated by costimulatory signals. In addition, it has been suggested that the inflammatory microenvironment associated with microbial infection might either directly suppress PD-1 expression on TCD8 or indirectly act by changing the state of tolerizing DCs.16 Our results do not exclude a role for inflammation in controlling PD-1 expression by either mechanism. However, we do demonstrate that costimulation via 4-1BB can directly inhibit PD-1 expression in the absence of inflammation. Finally, our demonstration that the lack of costimulation drives the rapid, high-level expression of PD-1 culminating in TCD8 deletion is not necessarily restricted to LEC-mediated deletion, but is likely to apply to additional models of peripheral deletion mediated by other APCs that express low or negligible levels of costimulatory molecules, such as FRCs and immature DCs.

Peripheral deletion has been previously associated with diminished expression of Bcl-xL and up-regulated Bim45,46 and PD-1 signaling has been associated with diminished expression of Bcl-xL in vitro.23 We have extended and linked these results to demonstrate that PD-1–mediated signaling in the context of peripheral tolerance in vivo inhibited Bcl-xL expression and induced expression of numerous proapoptotic molecules. Our results are also consistent with a model in which PD-1 determines the expression of these molecules indirectly by suppressing expression of the CD25 chain of IL-2R, although they do not preclude a direct effect as well. Previous work established that self-reactive TCD8 undergoing deletion in response to a cross-presented Ag also failed to express CD2547 and could not be rescued by IL-2,3 but deletion was not associated with CD25 expression, nor was it found to be PD-1 dependent. In contrast, PD-1 signaling leading to anergy has been associated with suppression of IL-2,37,39 and the anergic phenotype can be reversed by addition of IL-2, indicating that CD25 expression is not substantially impaired. It is not yet clear why PD-1 signaling can lead to these different outcomes and effects on CD25 expression. The level of antigen on APCs has been reported to determine whether cells undergo deletion or anergy.48 In the context of our results, high-level antigen, which is associated with anergy induction, might delay the expression of PD-1, allowing cells to re-express CD25, but ultimately leaving them susceptible to PD-1 signaling at a later point that would suppress IL-2 expression. It is also possible that the timing of PD-1 expression could enable interaction with inhibitory signaling pathways that predispose cells to become anergic, such as BTLA and LAG-3. Further work is necessary to illuminate these issues.

In the absence of PD-L1 or presence of costimulation, LECs serve as robust APCs that induce FH cell accumulation and effector differentiation, culminating in vitiligo. Thus, TCD8-mediated autoimmunity to peripheral tissue antigens presented by LECs28 might arise when the PD-L1:PD-1 pathway is blocked or when other LN-resident cells provide third-party costimulatory signals to self-reactive TCD8 engaged with LECs. While PD-L1−/− mice are more susceptible to the induction of autoimmune disorders, such as diabetes and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,49 they do not develop vitiligo spontaneously. This suggests that additional inhibitory mechanisms exist to control endogenous levels of autoreactive TCD8 in the absence of PD-1 signaling. However, autoimmunity in humans has been linked to polymorphisms in the PD-1 gene,49 suggesting that presentation of self-antigen by LECs with compromised PD-1 signaling could predispose to autoimmunity. Thus, enforcing PD-1 signaling or blocking costimulation to induce the up-regulation of inhibitory receptors on self-reactive T cells could be a useful therapeutic strategy for a variety of autoimmune disorders. In addition, LECs express at least 2 peripheral tissue antigens that are also tumor-associated antigens,28,50 tyrosinase, and the intestinal antigen A33.28 Thus, clinical responses to anti–PD-1 or anti–PD-L1 immunotherapy of advanced human cancers may be driven in part by rescuing TCD8 specific for these and other self-antigens from LEC-mediated tolerance. In this context, providing costimulation could be used therapeutically to reduce inhibitory receptor expression on TCD8 enabling them to persist and recognize tumor.

In summary, our work has provided new insights into the mechanisms by which LECs, a subset of LN stromal cells, induce deletional tolerance in TCD8. It particularly points to the role of PD-1, as opposed to other inhibitory molecules, in this process. It solidifies the understanding of how PD-1 engagement leads to deletion, and how PD-1 expression can be regulated by the quality of costimulation provided within the LN environment. The finding that costimulation through 4-1BB inhibits the up-regulation of PD-1 on TCD8 is likely to be of more general significance during presentation of antigens by other APCs that express low to negligible levels of costimulatory molecules. On the other hand, the finding that PD-L1 is most highly expressed in the LN by LECs suggests that they might also serve as quality control gatekeepers to determine the fate of emigrating TCD8 activated by other APCs. Finally, our work suggests that therapeutics that signal through PD-1 or inhibit costimulation could be useful in the treatment of autoimmune disorders while those that block PD-1 signaling or enforce costimulation could be useful to boost antitumor immunity based on enhanced self-reactivity.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank H. Davis, K. Cummings, and J. Gorman for excellent technical assistance, D. Vignali (St Jude Children's Research Hospital) for the LAG-3 C9B7W hybridoma, P. Marrack (National Jewish Health and University of Colorado Health Sciences Center) for the CD25 3C7 hybridoma, A. Farr (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) for the 10.1.1 hybridoma, the University of Virginia Research Histology Core for preparation of tissue sections, and the Engelhard laboratory for insightful discussions and advice.

This work was supported in part by US Public Health Service (USPHS) grant AI068836 (V.H.E.), PF-10-156-01-LIB from the American Cancer Society (E.F.T.), and USPHS training grant AI07496 (E.F.T, J.N.C., S.J.R.), GM007267 (J.N.C., S.J.R.), and CA44579 (C.J.G.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: E.F.T. designed and ran most of the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; J.N.C., S.J.R., and C.J.G. performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and edited the manuscript; H.Q. and S.P.F. performed experiments and analyzed and interpreted data; M.R.C. provided expertise and help with statistics; T.P.B. and K.S.T. provided reagents, technical expertise, and discussed and interpreted results; A.T.V., A.J.A., and L.C. provided reagents, technical expertise, discussed and interpreted results, and edited the manuscript; and V.H.E. headed the study, designed and interpreted experiments, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Victor H. Engelhard, Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Cancer Biology and Carter Immunology Center, University of Virginia, Bldg MR6, PO Box 801386, 345 Crispell Dr, Charlottesville, VA 22908; e-mail: vhe@virginia.edu.