Key Points

Knockdown of individual PRC1 members in human stem/progenitor cells revealed a lack of redundancy between various paralog family members.

CBX2 was identified as an important regulator of p21/CDKN1A independent of BMI1/PCGF4.

Abstract

The Polycomb group (PcG) protein BMI1 is a key factor in regulating hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and leukemic stem cell self-renewal and functions in the context of the Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1). In humans, each of the 5 subunits of PRC1 has paralog family members of which many reside in PRC1 complexes, likely in a mutually exclusive manner, pointing toward a previously unanticipated complexity of Polycomb-mediated silencing. We used an RNA interference screening approach to test the functionality of these paralogs in human hematopoiesis. Our data demonstrate a lack of redundancy between various paralog family members, suggestive of functional diversification between PcG proteins. By using an in vivo biotinylation tagging approach followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry to identify PcG interaction partners, we confirmed the existence of multiple specific PRC1 complexes. We find that CBX2 is a nonredundant CBX paralog vital for HSC and progenitor function that directly regulates the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21, independently of BMI1 that dominantly controls expression of the INK4A/ARF locus. Taken together, our data show that different PRC1 paralog family members have nonredundant and locus-specific gene regulatory activities that are essential for human hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are essential for proper cell lineage commitment and development during embryogenesis. Their activity is also crucial for accurate regulation of somatic stem cell self-renewal and is deregulated in various types of cancer.1,2 PcG proteins are involved in epigenetic repression of gene transcription and generally reside in 2 distinct complexes: Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2).3 According to the classical model for PcG-mediated repression, the PRC2 complex, by means of the methyltransferase EZH2, first trimethylates histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me3).4-6 This epigenetic modification recruits the 5-subunit PRC1 complex, most likely via the chromobox domain of the CBX subunit of the PRC1 complex.7,8 Subsequently, the PRC1 complex, via its RING1 subunit, can ubiquitinate histone H2A at Lysine 119 (H2AK119ub).9,10 In humans, each of the PRC1 components has multiple paralog family members: 6 PCGF members (PCGF1/NSPC1, PCGF2/MEL18, PCGF3, PCGF4/BMI1, PCGF5, and PCGF6/MBLR), 3 PHC members (PHC1, PHC2, and PHC3), 5 CBX members (CBX2, CBX4, CBX6, CBX7, and CBX8), 3 SCML members (SCML1, SCML2, and SMLH1), and 2 RING1 members (RING1A and RING1B). These paralogs allow a large diversity of distinct PRC1 complexes involved in PcG-mediated silencing.11 This idea was supported by the identification of BMI1- and MEL18-containing PRC1 complexes and similarly PRC1 complexes with mutually exclusivity of CBX paralogs.12-14 Very recently, PRC1 complexes that lack a CBX paralog family member but do contain RYBP or YAF2 and are targeted to PcG target genes independent of H3K27me3 were identified.15,16 Furthermore, some paralog family members like RING1A/B, NSPC1, and MBLR also reside in non-PRC1 complexes, such as the BCOR and E2F6 complexes.17-20 Taken together, these data suggest that many distinct PcG complexes exist with likely different functions.

A role for PcG proteins in hematopoiesis was first suggested by the phenotype of Bmi1−/− mice, which display reduced numbers of hematopoietic progenitors and more differentiated cells, eventually leading to hematopoietic failure.21 BMI1 has a key role in regulating hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) self-renewal in mice and humans by regulating symmetrical cell division.22-28 As a consequence, Bmi1−/− mice show severely reduced HSC numbers. Apart from normal hematopoiesis, BMI1 is also important for leukemic stem cell self-renewal as evidenced by loss of self-renewal and induction of apoptosis upon BMI1 knockdown in primary acute myeloid leukemia samples.23,26 Nevertheless, little information is available on the PRC1 complex composition in which BMI1 participates and whether different complexes exist in normal and leukemic stem and progenitor cells.

Methods

Primary cell isolation

Cord blood was isolated from healthy full-term pregnancies after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from the obstetrics departments at the Martini Hospital and University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the University Medical Center Groningen. CB CD34+ cells were isolated as described previously.29

Lentiviral transduction

All short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors were generated by MunI-SacII subcloning of the shRNA from the pLKO.1 puro vector (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) into the pLKO.1 green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector.30 pLKO.1 mCherry vectors were generated by swapping the BamHI-BsrGI mCherry fragment from the pRRL SFFV mCherry vector into the pLKO.1 GFP vector, thereby replacing GFP with mCherry (see supplemental Table 1 for shRNA sequences). CD34+ cells were prestimulated and transduced as described previously.29 One transduction round was performed. Cells were harvested at day 2 after transduction.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting procedures

Prior to staining, transduced cells were blocked with anti-human FcR block (Stem Cell Technologies). Cells were stained with either Allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti-CD34 (581, BD) alone or in combination with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD38 (HB7, BD). For fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses of MS5 stromal cocultures, cells were also blocked anti-human FcR block and subsequently stained with pacific blue–conjugated anti-CD15 (H198, eBioscience), PE-conjugated anti-CD14 (HCD14, Biolegend), and PE-Cy7–conjugated anti-CD34 (8G12, BD). For annexin V stains, transduced cells were stained with APC–conjugated annexin V (IQProducts) and PE-conjugated CD34 (8G12, BD). Cell sorts were performed on a MoFlo Astrios (Beckman Coulter). Analyses were done on a LSR-II (Becton Dickinson). Data were analyzed using FlowJo version 7.6.1 software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

MS5 cocultures and liquid cultures

MS5 stromal cells for cocultures were cultured in α-minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. For MS5 cocultures, 50 000 CD34+ cells were plated in T25 flasks precoated with MS5 stromal cells in long-term culture (LTC) medium (Gartner’s).29 Cultures were demidepopulated each week. For stroma-independent liquid cultures, CB CD34+ cells were cultured in IMD medium (PAA Laboratories) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum, penicillin and streptomycin, 20 ng/mL stem cell factor, and 20 ng/mL interleukin-3. For single-cell cultures, cells were seeded at single-cell density in Terasaki plates in liquid culture medium.

CFC and LTC-IC assays

For colony-forming cell (CFC) assays, 1000 GFP+CD34+ cells were plated in duplicate in 1 mL methylcellulose (H4230, Stem Cell Technologies) supplemented with 20 ng/mL interleukin-3, interleukin-6, stem cell factor, granulocyte CSF, Flt-3L, 10 ng/mL granulocyte macrophage CSF, and 1 U/mL Epo. Colonies were scored after 2 weeks. For replating, cultures were harvested and pooled and 200 000 cells were plated in 1 mL methylcellulose in duplicate. For the LTC initiating-cell (IC) assays, cells were sorted on MS5 stromal cells in limiting dilutions from 25 to 13 125 cells per well in 96-well plates. Medium of the cultures was replenished on a weekly basis. After 5 weeks, the medium was removed and replaced with methylcellulose supplemented with the same cytokines as listed above. After a further 2 weeks, wells were scored as positive or negative for CFC and LTC-IC frequencies were calculated using L-Calc software (Stem Cell Technologies).

RNA isolation and qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from ∼2 × 105 cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Amplification of cDNA was performed using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad) on a MyIQ thermocycler (Bio-Rad) and quantified using MyIQ software (Bio-Rad). RPL27 expression was used to calculate relative expression levels. Primer sequences are available on request. The depicted quantitative polymerase chain reactions (qPCRs) are representative experiments of at least 3 independent experiments, and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean of 3 sample replicates.

ChIP

Chromatin immune precipitation analysis (ChIP) analysis was essentially performed as described previously.31 Briefly, CB CD34+ cells were prestimulated for 2 days and crosslinked. Alternatively, cells were crosslinked after 14 days liquid culture when indicated in the text. ChIP reactions were performed using the following antibodies: αCBX2 (Y-23, Santa Cruz), αBMI1 (AF27, K. Helin), αH3K27me3 (07-449, Millipore), αH2AK119ub (D27C4, Cell Signaling Technology), and αGFP (ab290, Abcam). ChIP efficiencies were assessed using qPCR. The depicted qPCRs are the average of at least 3 independent experiments, and the error bars represent the standard deviation across these experiments. Primer sequences are available on request.

Antibodies

For western analysis, the following antibodies were used: p16 (C-20, Santa Cruz), p21 (EA10, Merck), p53 (DO-1, Santa Cruz), Bax (N-20, Santa Cruz), BMI1 (F6, Millipore), RING1B (H. Koseki), and β-actin (C4, Santa Cruz),

Additional methods on the cloning of vectors, in vivo biotinylation strategy, and proteomics analyses can be found in the supplemental data.

Results

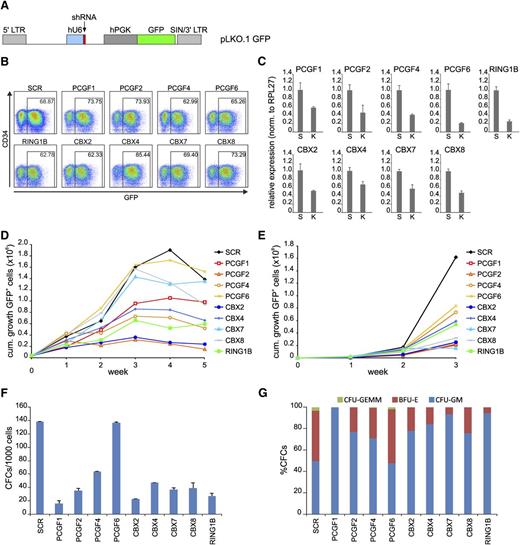

To study the functional role of various PRC1 subunits in human hematopoiesis, we knocked down various members of the PCGF, CBX, and RING1 paralog families in cord blood (CB) CD34+ cells using pLKO.1 GFP shRNA lentiviral vectors (Figure 1A). Transduction efficiencies as measured by GFP expression at day 2 after transduction were very similar (60%-85%; Figure 1B). qPCR analysis of the various targeted transcripts in the transduced GFP+ cell population showed a downregulation ranging from 40% to 80% compared with scrambled (SCR) controls (Figure 1C). To study whether knockdown of these genes would affect cell viability and/or proliferation, we initiated unsorted MS5 stromal cocultures. Plotting the cumulative expansion of GFP+ cells showed that many PRC1 paralog knockdowns induced a proliferative disadvantage compared with SCR control cultures, suggesting an important role for these genes in regulating cell proliferation in CB CD34+ cells (Figure 1D). FACS profiles of all various knockdown cells did not show changes in expression of myeloid markers, except for PCGF1 shRNA-expressing cells, which showed a more rapid loss of CD34+ cells and skewing toward CD15+ at week 1 and 2 of the cocultures (supplemental Figure 1). These data indicate that in general myeloid differentiation is not regulated by PRC1 paralog family members, although we cannot exclude the possibility that in some cases knockdown might not have been efficient enough to uncover biological phenotypes. Liquid culture experiments showed a phenotype comparable to the MS5 cocultures, where most PRC1 paralog knockdowns resulted in a competitive disadvantage compared with nontransduced cells (Figure 1E). Interestingly, in contrast to MS5 cocultures, knockdown of CBX7 and CBX8 did negatively affect cell growth in liquid cultures. To read out progenitor phenotypes, CFC frequency of GFP+ CD34+ cells was measured (Figure 1F). Clearly, except for PCGF6 knockdown cells, all PRC1 paralog family member knockdowns resulted in a reduction in CFC frequency. However, the most dramatic reduction in CFC frequency among the PCGF and CBX paralog family members was observed with PCGF1 and CBX2. Morphologic analyses of the colonies showed a mild skewing toward myeloid differentiation (Figure 1G). We also determined the specificity of our shRNA vectors (supplemental Figure 2). These experiments showed that short-hairpin vectors against CBX members were quite specific. The same was true for hairpins against PCGF members, with the exception of hairpins against PCGF1 that also downmodulated other PCGF members. Thus, we cannot interpret the data of PCGF1 shRNA-transduced cells as being specific for PCGF1. Among the tested CBX paralogs (CBX2, 4, 7, and 8), knockdown of CBX2 induced the most dramatic phenotype in MS5 stromal cocultures, liquid cultures, and CFC frequency analyses. The lack of functional complementation by other CBX paralog family members indicates that CBX2 is a nonredundant CBX paralog family member, highly important for human hematopoietic cell proliferation.

PRC1 paralog family members show lack of redundancy in human CD34+ cord blood (CB) cells. (A) Schematic representation of the lentiviral pLKO.1 GFP vector. (B) FACS analysis of transduced CD34+ CB cells at day 2 after transduction. (C) qPCR analyses of a representative experiment showing knockdown efficiency of the various shRNAs. SCR and the specified knockdown are indicated with “S” and “K,” respectively. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. (D) Cumulative expansion of GFP+ cells in bone marrow stromal cocultures on MS5 cells. (E) Cumulative expansion of GFP+ cells in liquid culture assays. (F) The effects of knockdown of PRC1 members on progenitor frequencies (F) and subtype (G) as determined by CFC assays. cum., cumulative.

PRC1 paralog family members show lack of redundancy in human CD34+ cord blood (CB) cells. (A) Schematic representation of the lentiviral pLKO.1 GFP vector. (B) FACS analysis of transduced CD34+ CB cells at day 2 after transduction. (C) qPCR analyses of a representative experiment showing knockdown efficiency of the various shRNAs. SCR and the specified knockdown are indicated with “S” and “K,” respectively. Error bars indicate standard deviation of triplicate measurements. (D) Cumulative expansion of GFP+ cells in bone marrow stromal cocultures on MS5 cells. (E) Cumulative expansion of GFP+ cells in liquid culture assays. (F) The effects of knockdown of PRC1 members on progenitor frequencies (F) and subtype (G) as determined by CFC assays. cum., cumulative.

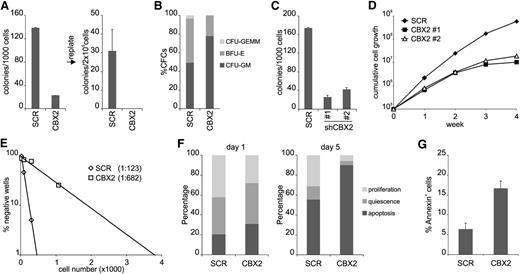

To investigate the effect of CBX2 knockdown on progenitor expansion more thoroughly, we performed CFC assays but now also investigated replating efficiency. CBX2 shRNA expression resulted in a marked reduction in CFC plating efficiency and a loss of replating potential (Figure 2A). Overall, colony morphology was not changed although a slight skewing was observed toward myeloid colonies (Figure 2B). Expression of a second independent CBX2 hairpin also resulted in downregulation of CBX2 messenger RNA (mRNA) and CFC analysis showed a comparable reduction in colony formation using either hairpin (Figure 2C). To investigate if the effect of CBX2 knockdown was cell intrinsic, we initiated sorted cytokine-driven liquid cultures in a stroma-free system. Clearly, CBX2 knockdown resulted in a strong reduction in proliferative capacity, irrespective of the used hairpin (Figure 2D). To check whether the HSC compartment was also affected by CBX2 knockdown, we performed limiting-dilution LTC-IC assays. Strikingly, CBX2 knockdown resulted in a prominent ∼5-fold reduction of LTC-IC frequency, indicating that both progenitor and HSC compartments are controlled by CBX2 (Figure 2E). To better understand the CBX2 knockdown phenotype in HSCs and progenitors, we initiated single-cell cultures in Terasaki plates and monitored their growth behavior. CD34+CD38− CB cells expressing SCR or CBX2 shRNAs were plated at single-cell density under liquid culture conditions and plating efficiency was assessed shortly after seeding the cells (Figure 2F). Here, a representative experiment out of 3 independent experiments is shown (n = 120 per group) where wells were scored as apoptotic (no cell), quiescent (1 cell), or proliferating (>1 cell). At day 1 after seeding, shCBX2-expressing cells already showed an increase in apoptosis and a decrease of wells with proliferation. At day 5, this phenotype was much more pronounced as illustrated by a strong increase of wells with apoptosis and a dramatic reduction in wells with quiescent or proliferating cells. Cell counts of proliferating wells showed that CBX2 knockdown cells had a clear proliferative disadvantage compared with SCR cells (supplemental Figure 3). These data indicate that upon knockdown of CBX2, both cell cycle and apoptosis are affected. Apoptosis induction was further confirmed by an increase in annexin V positivity of shCBX2-expressing CB CD34+ cells derived from liquid cultures at day 5 after transduction (Figure 2G).

CBX2 is required for both hematopoietic stem and progenitor self-renewal. (A) CFC analysis and subsequent replating of SCR and CBX2 CD34+ knockdown cells. (B) CFC colonies were scored on the basis of morphology as CFU-GEMM, BFU-E, and CFU-GM. (C) CFC analysis of transduced CD34+ CB cells using 2 distinct shCBX2 hairpin vectors (#1 and #2). (D) Liquid culture of sorted SCR and CBX2 knockdown (#1 and #2) cells. (E) Representative experiment of limiting-dilution LTC-IC analysis of SCR and CBX2 knockdown cells. (F) Representative experiment of single-cell cultures of transduced CD34+CD38− cells. Wells without cells were annotated as apoptosis, wells with 1 cell as quiescent, and wells with >1 cell as proliferation. (G) Annexin V staining of transduced CD34+ cells after 3 days of liquid culture (n = 2).

CBX2 is required for both hematopoietic stem and progenitor self-renewal. (A) CFC analysis and subsequent replating of SCR and CBX2 CD34+ knockdown cells. (B) CFC colonies were scored on the basis of morphology as CFU-GEMM, BFU-E, and CFU-GM. (C) CFC analysis of transduced CD34+ CB cells using 2 distinct shCBX2 hairpin vectors (#1 and #2). (D) Liquid culture of sorted SCR and CBX2 knockdown (#1 and #2) cells. (E) Representative experiment of limiting-dilution LTC-IC analysis of SCR and CBX2 knockdown cells. (F) Representative experiment of single-cell cultures of transduced CD34+CD38− cells. Wells without cells were annotated as apoptosis, wells with 1 cell as quiescent, and wells with >1 cell as proliferation. (G) Annexin V staining of transduced CD34+ cells after 3 days of liquid culture (n = 2).

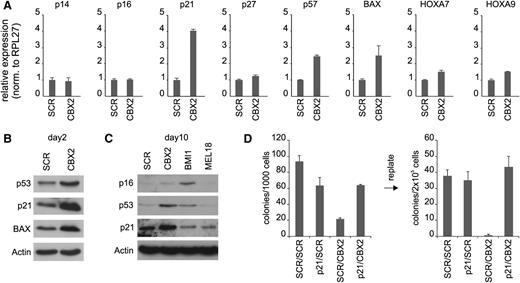

To understand the molecular cause underlying the observed phenotype in CBX2 knockdown cells, we performed transcriptome analysis of cells expressing either SCR of CBX2 shRNAs. Gene set enrichment analysis showed a significant enrichment of genes with Gene Ontology annotations “negative regulation of cell cycle” and “apoptosis” among the shCBX2-up transcripts (supplemental Figure 3). Furthermore, we observed an enrichment for p53 target genes (16 out of 690 genes) among the upregulated transcripts (>1.5-fold change) vs downregulated transcripts (2 out of 742 genes; <1.5-fold change) in CBX2 knockdown cells. Because p53 signaling is activated by the expression of p14ARF, which is transcribed from the classical Polycomb target gene CDKN2A, we investigated whether expression of p14ARF and p16INK4A was increased in CBX2 knockdown cells. Surprisingly, the expression of both transcripts, as measured by qPCR at day 4 after transduction, was not affected by knockdown of CBX2 (Figure 3A). Analysis of 2 other classical Polycomb target genes, HOXA7 and HOXA9, showed a marginal increase upon CBX2 knockdown. Strikingly, CBX2 knockdown did result in a strongly increased expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and, to a lesser extent, of p57 (Figure 3A). In addition, the p53 target gene BAX, a proapoptotic protein, was also increased in CBX2 knockdown cells. Western blot analysis at day 2 after transduction confirmed the upregulation of p21 and BAX at the protein level and also showed increased expression of p53 in CBX2 knockdown cells (Figure 3B).

CBX2 knockdown induces p21 and p14ARF expression and p21 knockdown partially rescues the CBX2 knockdown phenotype. (A) qPCR analysis of mRNA levels in SCR and CBX2 knockdown cells from liquid cultures at day 4 after transduction. (B) Western blot analysis of shSCR/shCBX2-expressing cells at day 2 after transduction. (C) Western blot analysis of SCR, CBX2, BMI1, and MEL18 shRNA-expressing cells at day 10 after transduction. (D) CFC analysis of freshly transduced and replates of cells expressing SCRGFP/SCRCFP, p21GFP/SCRCFP, SCRGFP/CBX2CFP, or p21GFP/CBX2CFP shRNAs.

CBX2 knockdown induces p21 and p14ARF expression and p21 knockdown partially rescues the CBX2 knockdown phenotype. (A) qPCR analysis of mRNA levels in SCR and CBX2 knockdown cells from liquid cultures at day 4 after transduction. (B) Western blot analysis of shSCR/shCBX2-expressing cells at day 2 after transduction. (C) Western blot analysis of SCR, CBX2, BMI1, and MEL18 shRNA-expressing cells at day 10 after transduction. (D) CFC analysis of freshly transduced and replates of cells expressing SCRGFP/SCRCFP, p21GFP/SCRCFP, SCRGFP/CBX2CFP, or p21GFP/CBX2CFP shRNAs.

The fact that p53 targets were upregulated independent of p14ARF expression tempted us to speculate that the p14-HDM2-p53-p21 axis is controlled at multiple levels by distinct PRC1 complexes. Indeed, we observed differences in gene expression changes upon knockdown of specific Polycomb genes (supplemental Figure 4 and Figure 3C). CB cells expressing shRNAs directed against BMI1, a classical repressor of the CDKN2A locus, showed a strong upregulation of p14ARF and p16INK4A compared with SCR cells, although not until 7 to 10 days after transduction. In contrast, p21 was not increased in BMI1 knockdown cells. As expected, CBX2 knockdown resulted in an increased p21 expression in the absence of p14ARF upregulation. Interestingly, when CBX2 knockdown cultures were followed for longer periods an increase in p14ARF expression was observed, although never as prominent as in BMI1 knockdown cells (supplemental Figure 5). Expression levels of p16INK4A were not changed in CBX2 knockdown cells. Knockdown of the BMI1 paralog family member MEL18 did not show increased expression of p14ARF, p16INK4A, p21, or BAX at later stages in liquid cultures. This indicates that the severe phenotype observed in MEL18 knockdown MS5 cocultures (Figure 1C) is not a consequence of a deregulated p14-p53-p21 axis. Western blot analysis of SCR, CBX2, BMI1, and MEL18 knockdown cells at day 10 after transduction confirms that only BMI1 knockdown cells show an upregulation of p16 but not (or only slightly) of p21 and p53. CBX2 knockdown cells show a very low p16 expression but a clear upregulation of p21 and p53. Taken together, these data suggest that CBX2 may directly regulate the expression of p21 in a manner independent of BMI1. Contrastingly, p14ARF expression likely is regulated both by CBX2 and BMI1. To further validate p21 as an important CBX2 target and p21 upregulation as a crucial event for the phenotype of CBX2 knockdown cells, we tried to rescue the CBX2 knockdown phenotype by concomitant CBX2 and p21 shRNA expression. Therefore, we cotransduced CB CD34+ cells using pLKO.1 CFP SCR/CBX2 and pHR′trip GFP SCR/p21 knockdown vectors. CFC analysis was performed and a representative experiment is shown in Figure 3D. As expected, SCRGFP/CBX2CFP transduced cells showed a strong reduction in CFC frequency as compared with SCRGFP/SCRCFP transduced cells. However, p21GFP/CBX2CFP double-knockdown cells clearly showed a partial rescue of the CBX2 knockdown phenotype, indicating that this phenotype can to a large extent be explained by an induction of p21 expression. Replating experiments further supported this conclusion, because SCRGFP/CBX2CFP cells displayed a loss of replating potential whereas p21GFP/CBX2CFP cells showed a frequency of secondary CFCs that was comparable to SCRGFP/SCRCFP cells (Figure 3D).

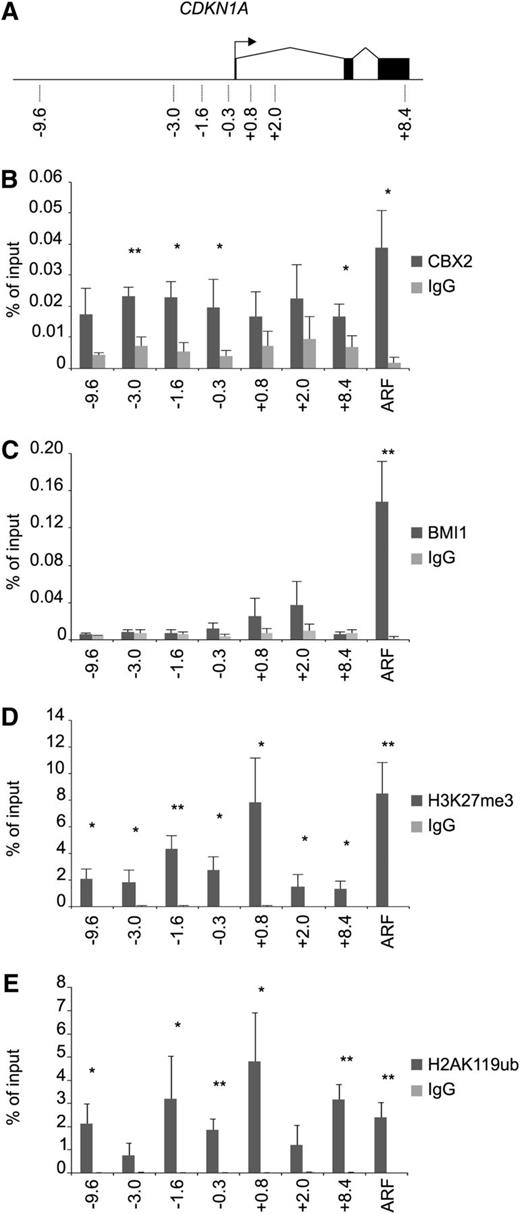

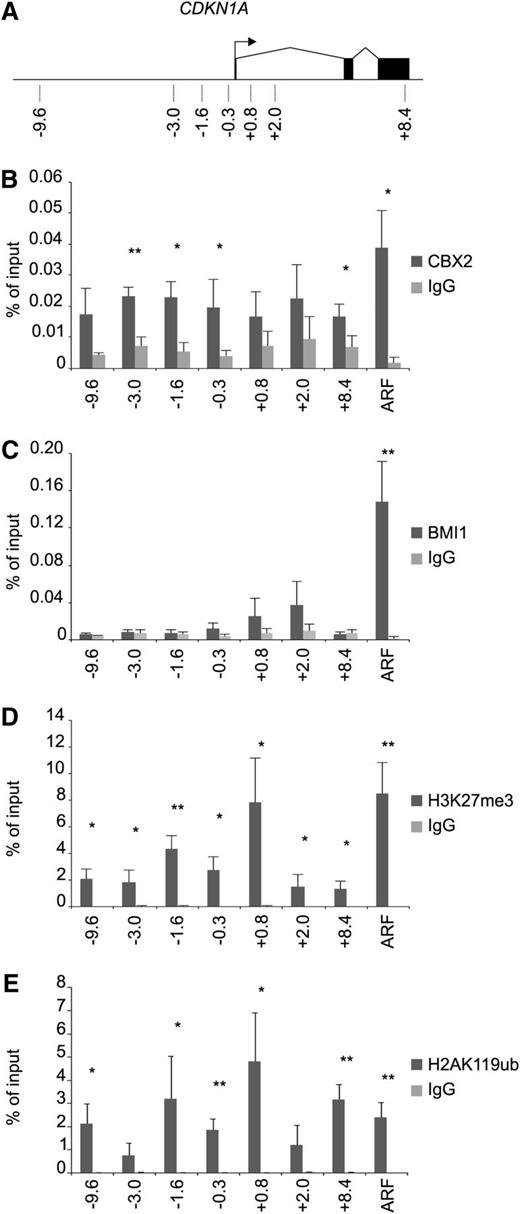

To verify that p21 is indeed directly targeted by CBX2 in CB CD34+ cells, we performed ChIP analysis on the CDKN1A locus (p21) and the p14ARF transcription start site (TSS; Figure 4A). These experiments clearly showed an enrichment of CBX2 on the p21/CDKN1A locus compared with the immunoglobulin G control (Figure 4B). In addition, the p14ARF TSS was also targeted by CBX2. BMI1 strongly occupied the p14ARF promoter, whereas no significant binding of BMI1 was observed at the p21 locus (Figure 4C). Analysis of H3K27me3 levels at the p21 gene and the p14ARF promoter showed the presence of the PRC2 mark at both genes at comparable levels (Figure 4D). H3K27me3 levels were found most prominently around the TSS of p21. H2AK119ub ChIP experiments showed a strong enrichment for this mark on the p21 locus and the p14ARF TSS in a manner that mimicked the H3K27me3 ChIPs (Figure 4E). These data show that the p21 locus in human CB CD34+ cells is targeted by a functional PRC1 and PRC2 complex. The fact that CBX2 was enriched both at the p14ARF and p21 loci, whereas BMI1 was not enriched at the p21 promoter, suggests the presence of distinct PRC1 complexes at these gene loci.

CBX2 directly targets the p21 gene in a BMI1-independent manner. (A) Schematic representation of the CDKN1A gene with locations of primers as indicated. (B) CBX2 ChIP analyses of prestimulated CB CD34+ cells on p21 gene and p14ARF promoter. (C) BMI1 ChIP on the p21 gene locus and the p14ARF promoter. (D) H3K27Me3 ChIP experiments showing enrichment across the p21 gene and the p14ARF promoter. (E) H2AK119ub ChIP analyses on the p21 and p14ARF loci. ChIP experiments are depicted as percentage of input and the data represent the average of 3 independent experiments on different CB batches. Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. Mean ± standard deviation (*P < .05, **P < .005). IgG, immunoglobulin G.

CBX2 directly targets the p21 gene in a BMI1-independent manner. (A) Schematic representation of the CDKN1A gene with locations of primers as indicated. (B) CBX2 ChIP analyses of prestimulated CB CD34+ cells on p21 gene and p14ARF promoter. (C) BMI1 ChIP on the p21 gene locus and the p14ARF promoter. (D) H3K27Me3 ChIP experiments showing enrichment across the p21 gene and the p14ARF promoter. (E) H2AK119ub ChIP analyses on the p21 and p14ARF loci. ChIP experiments are depicted as percentage of input and the data represent the average of 3 independent experiments on different CB batches. Statistical analysis was performed using Student t test. Mean ± standard deviation (*P < .05, **P < .005). IgG, immunoglobulin G.

To independently validate the presence of CBX2 on the p21 locus, we transduced CB CD34+ cells with either pRRL SFFV GFP-CBX2 or pRRL SFFV GFP virus and ChIP experiments were performed using either anti-GFP antibody or immunoglobulin G as a control. Strong enrichment of GFP-CBX2, but not GFP, on the p21 promoter was observed (Figure 5A), which was reduced upon knockdown of CBX2 (Figure 5C). The clear drop in mean fluorescence intensity of GFP-CBX2 cells cotransduced with shCBX2 vectors confirmed efficient knockdown of CBX2 at the protein level (Figure 5B). Furthermore, enrichment of GFP-CBX2 at the p14ARF locus was observed, which again was reduced upon downmodulation of CBX2 (Figure 5A,C). Using a similar approach, we also analyzed whether BMI1-GFP or MEL18-GFP could bind the p21 promoter. ChIP analyses showed that whereas GFP-CBX2 was strongly enriched at the p21 locus, BMI-GFP and MEL18-GFP were not (supplemental Figure 6A). As expected, we did find enrichment of BMI1-GFP on the p14ARF promoter. Similarly, we observed MEL18-GFP binding to the p14ARF promoter, although levels were lower compared with BMI1-GFP (supplemental Figure 6B). MEL18 was previously shown to bind to various HOX clusters.12 Our ChIP experiments confirmed these data and showed that MEL18-GFP was efficiently targeted to the HOXA9 and HOXA13 promoters, which was also observed for BMI-GFP (supplemental Figure 6B).

GFP-CBX2 binds to the p21 and p14ARF loci, which is reduced upon knockdown of CBX2. (A) CB CD34+ cells were transduced with GFP control or GFP-CBX2 vectors, cells were expanded in liquid culture for 12 days, and ChIP experiments were performed on the p14ARF and p21 loci. (B-C) Experiment was performed as in panel A, but cells were cotransduced with pLKO.1 mCherry shRNA vectors against SCR or CBX2. The reduced mean fluorescence intensity of GFP confirmed efficient knockdown of CBX2 protein (B), which coincided with reduced CBX2 binding to p14ARF and p21 loci (C). IgG, immunoglobulin G.

GFP-CBX2 binds to the p21 and p14ARF loci, which is reduced upon knockdown of CBX2. (A) CB CD34+ cells were transduced with GFP control or GFP-CBX2 vectors, cells were expanded in liquid culture for 12 days, and ChIP experiments were performed on the p14ARF and p21 loci. (B-C) Experiment was performed as in panel A, but cells were cotransduced with pLKO.1 mCherry shRNA vectors against SCR or CBX2. The reduced mean fluorescence intensity of GFP confirmed efficient knockdown of CBX2 protein (B), which coincided with reduced CBX2 binding to p14ARF and p21 loci (C). IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Next, we used a proteomics approach to identify PcG protein interaction partners and study the diversity of PRC1 complexes. We used an in vivo biotinylation strategy using retroviral vectors expressing Avi-tagged PcG proteins and a GFP-BirA fusion from the same mRNA.32 Figure 6A shows the Avi-PCGF4/BMI1 expression vector and the GFP-BirA control vector. K562 cells were transduced and stable cell lines were generated in which Avi-PCGF4/BMI1 was expressed at similar levels compared with endogenous BMI1 (Figure 6B, I is input fraction). Avi-PCGF4/BMI1 strongly precipitated with streptavidin beads in the bound fraction (B) while Avi-PCGF4/BMI1 was selectively depleted from the nonbound fraction (NB), showing the efficacy of our approach. Similarly, we generated vectors for Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2/MEL18, Avi-RING1A, and CBX2-Avi. Streptavidin pullouts were performed on stably transduced K562 lines, followed by western blot analysis using antibodies directed against BMI1 and RING1B (Figure 6C). Again, BMI1 was efficiently precipitated from the Avi-PCGF4/BMI1 cells. Furthermore, CBX2 and RING1A, but not PCGF1 or PCGF2/MEL18, interacted with BMI1, suggesting that only one PCGF member can participate within the PRC1 complex, and that BMI1 and MEL18 are mutually exclusive. In addition, RING1B interacted with CBX2, PCGF2, and PCGF4, but not RING1A, again indicating that RING1 proteins are mutually exclusive within the PRC1 complex (Figure 6C). Next, large-scale pullout experiments and LC-MS Orbitrap analysis were performed. Figure 6D provides a summary of coprecipitated PcG proteins with the Avi-tagged proteins. Importantly, none of the PcG proteins identified in the Avi pullouts were detected in the BirA control pullouts. Numbers indicate the number of uniquely identified peptides in the analysis. Interactions between Avi-RING1A and all known PCGF paralogs were identified. CBX2 only precipitated with PCGF2 and 4, and PCGF1, 2, and 4 proteins most likely act in a mutually exclusive manner within PRC1 complexes (Figure 6D). CBX2 itself was efficiently precipitated in the CBX2-Avi pullout, but remarkably some CBX4 and CBX8 were also identified within the CBX2 pullouts. Avi-RING1A complexes contained CBX2, CBX4, and CBX8, but not CBX7. Furthermore, no RING1B was identified in the RING1A pullouts, suggesting that also RING1A and RING1B are mutually exclusive in the PRC1 complex in K562 cells. Finally, CBX2-Avi pullouts selective failed to coprecipitate RYBP and YAF2, whereas their presence in Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2, Avi-PCGF4, and Avi-RING1A complexes was confirmed, in line with recently published data.15,16 Taken together, these data show that in K562 cells many different PRC1 complexes exist with likely unique and specific functions. This might also underlie the diversity in phenotypes of PRC1 paralog knockdowns in human CD34+ CB cells and suggests that the specific phenotype of CBX2 depletion on the p21 promoter likely is a consequence of depletion of a specific type of PRC1 complex.

Proteomic analysis reveals mutually exclusivity of PRC1 paralog family members in PRC1 complexes. (A) Schematic representation of retroviral vectors expressing a bicistronic mRNA resulting in expression of Avi-tagged PCGF4/BMI1 and GFP-BirA. MSCV IRES GFP-BirA was used as a negative control. (B) Anti-BMI1 western blot showing input (I), nonbound (NB), and bound (B) fraction of streptavidin pullout of Avi-BMI1 from K562 cells stably expressing Avi-BMI1. (C) Western analyses showing input (I), nonbound (NB), and bound (B) fraction of BirA, CBX-Avi, Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2/MEL18, Avi-PCGF4/BMI1, and Avi-RING1A pullouts. Blot was stained using BMI1 and RING1B antibodies. (D) Table showing number of unique peptides of PcG proteins coprecipitated with Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2, Avi-PCGF4, CBX2-Avi, or Avi-RING1A.

Proteomic analysis reveals mutually exclusivity of PRC1 paralog family members in PRC1 complexes. (A) Schematic representation of retroviral vectors expressing a bicistronic mRNA resulting in expression of Avi-tagged PCGF4/BMI1 and GFP-BirA. MSCV IRES GFP-BirA was used as a negative control. (B) Anti-BMI1 western blot showing input (I), nonbound (NB), and bound (B) fraction of streptavidin pullout of Avi-BMI1 from K562 cells stably expressing Avi-BMI1. (C) Western analyses showing input (I), nonbound (NB), and bound (B) fraction of BirA, CBX-Avi, Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2/MEL18, Avi-PCGF4/BMI1, and Avi-RING1A pullouts. Blot was stained using BMI1 and RING1B antibodies. (D) Table showing number of unique peptides of PcG proteins coprecipitated with Avi-PCGF1, Avi-PCGF2, Avi-PCGF4, CBX2-Avi, or Avi-RING1A.

Discussion

Using an RNA interference screen in primary human hematopoietic cells, we were able to identify a set of nonredundant PRC1 paralog family members that are highly important for hematopoiesis. Among the CBX paralog family members, CBX2 knockdown resulted in the most prominent phenotype, which was illustrated by a loss of HSCs and progenitors, decreased cell proliferation, and an increase in apoptotic events. Interestingly, previously performed competitive repopulation experiments using CBX2 (M33) knockout fetal liver cells showed no effects on HSC function.22 It is possible that these differences are a consequence of species-specific differences in CBX2 function. For example, we find p21 to be a bona fide target of CBX2/PRC1 and PRC2 complexes whereas p21 has not been annotated as a Polycomb target gene in mouse cells. Recently, 2 independent studies also reported different functional modalities between CBX paralog family members in mouse embryonic stem cells.33,34 These data show a key role for CBX7 in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells whereas CBX2 and CBX4 are essential for lineage commitment. We observed a high expression of CBX2 and CBX4 in primary human cord blood cells whereas CBX7 is expressed at low levels (supplemental Figure 7), which is in line with the most dominant phenotypes observed upon knockdown of CBX2 and CBX4. These data were further confirmed by published gene expression data sets of CB HSCs, progenitors, and differentiated cells by Noverhstern et al35 and Fatrai et al36 (supplemental Figure 8). Clearly, these data highlight important cell-type–specific differences in expression and functionality of PRC1 members.

Our gene expression and ChIP studies show that upon CBX2 knockdown we find a direct upregulation of p21 and a late induction of p14ARF expression. The difference in timing of transcriptional activation after CBX2 knockdown is likely a consequence of a different PRC1 context. P14ARF is part of the CDKN2A locus, a classical PcG target, which has been studied in detail and is known to harbor various PcG proteins in a variety of cell models. Although both the p14ARF promoter and the p21 locus are targeted by CBX2, the first is also bound by BMI1 whereas the second is regulated in a BMI1-independent manner. The fact that we found CBX2, H3K27me3, and H2AK119ub marking at the p21 locus, but not BMI1 or MEL18, suggests that CBX2 is incorporated here in an alternative PRC1 complex with another member of the PCGF paralog family. A promising candidate might be PCGF1 (NSPC1), which was previously reported to directly repress p21 expression by competing with retinoic acid receptors for the retinoic acid responsive element that is located at the −1357 to −1083 region in the p21 promoter.37 Future studies are required to analyze the potential role of PCGF1 in PRC1-mediated repression of the human p21 locus in further detail.

Our proteomics data clearly show that there are many distinct types of PRC1 complexes present in hematopoietic cells, likely with important differences in terms of gene regulatory functions and target specificity. Using an in vivo biotinylation approach, we were able to efficiently coprecipitate many PcG proteins. These data show that within PRC1 complexes, PCGF paralog family members most likely act in a mutually exclusive manner in the PRC1 complex. Similarly, RING1B does not coprecipitate with RING1A and RYBP and YAF2 do not coprecipitate with CBX2, whereas these latter proteins were detected in all other performed PRC1 pullouts. These data are in line with the recent identification of PRC1 complexes that contain RYBP or YAF2 but are devoid of CBX paralog family members.15,16 As a consequence, these data point toward a previously unanticipated complexity of PcG protein biology and likely a diverse range of functional modalities between various PRC1 paralog family members. This might also explain the striking differences in phenotype we have observed upon PRC1 paralog knockdown and the lack of redundancy between the various paralog family members.

Now that we are beginning to understand the role of various PRC1 paralog family members in human hematopoiesis, the next step will be to see if their function is deregulated in various hematopoietic malignancies. Although the role of the PRC1 complex member BMI1 in leukemic stem cell self-renewal has been investigated quite thoroughly, recent results also indicate a role for CBX8 in MLL-AF9–induced leukemia.38 The fact that many PcG proteins show a deregulated expression or are mutated in various types of cancer2 suggests that we are just beginning to understand how PcG proteins contribute to the development of leukemia and other malignancies.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the help of Dr J. J. Erich and Dr A. van Loon and colleagues (Departments of Obstetrics, University Medical Center Groningen and Martini Hospital Groningen) for collecting cord blood. The authors thank Kirin for supplying TPO, Amgen for supplying Flt-3L and SC, and Sjaak Philipsen and Harald Braun for kindly sharing reagents and protocols for the in vivo biotinylation experiments. The retroviral GFP-CBX2 construct was obtained from Pierre-Olivier Angrand. The authors thank Kristian Helin and Haruhiko Koseki for providing the BMI1 AF27 and RING1B monoclonal antibodies, respectively, Bauke de Boer and Henny Maat for generation of GFP-fusion constructs, and Henk Moes, Geert Mesander, and Roelof-Jan van der Lei for help with cell sorting.

This work is supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Foundation (RUG 2009-4275) and by grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (G.M. and G.V.).

Authorship

Contribution: V.v.d.B., M.R.-G., F.B., D.v.G., A.M.H., F.F., and J.J.S. performed experiments and analyzed data. D.M., G.V., and G.M. provided and functionally tested the shRNA vectors. V.v.d.B., E.V., and J.J.S. analyzed and discussed data. V.v.d.B. and J.J.S. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jan Jacob Schuringa, Department of Experimental Hematology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Hanzeplein 1, 9700RB Groningen, The Netherlands; e-mail: j.j.schuringa@umcg.nl.