In this issue of Blood, Bakchoul et al and Lee et al describe and characterize a common but only recently recognized immune response to protamine after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery with potential important clinical implications.1,2

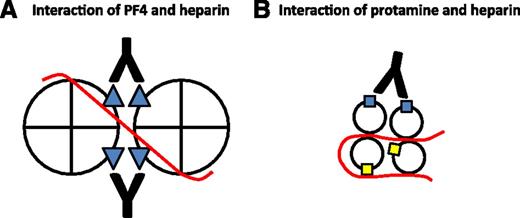

Potential role of heparin in the immune responses to PF4 and protamine. Heparin (red line) binds to PF4 and neutralizes cationic charge repulsion between tetramers, forming oligomeric complexes (shown here as a dimer for simplicity) that approximate anti-PF4/heparin (HIT antibody) binding sites (blue triangles). Close apposition of epitopes allows a single antibody to bind adjacent tetramers, thereby increasing antibody avidity (A). Heparin may also oligomerize protamine and approximate some immunogenic epitopes (blue squares) while obscuring others (yellow squares) from antibody binding (B). Panel A is adapted from Sachais et al, Blood. 2012; 120(5):1137-1142.10

Potential role of heparin in the immune responses to PF4 and protamine. Heparin (red line) binds to PF4 and neutralizes cationic charge repulsion between tetramers, forming oligomeric complexes (shown here as a dimer for simplicity) that approximate anti-PF4/heparin (HIT antibody) binding sites (blue triangles). Close apposition of epitopes allows a single antibody to bind adjacent tetramers, thereby increasing antibody avidity (A). Heparin may also oligomerize protamine and approximate some immunogenic epitopes (blue squares) while obscuring others (yellow squares) from antibody binding (B). Panel A is adapted from Sachais et al, Blood. 2012; 120(5):1137-1142.10

Protamines are small, positively charged, DNA-binding proteins found in the sperm of invertebrate and vertebrate animals. Protamine sulfate, derived from salmon sperm, is used to reverse the anticoagulant activity of unfractionated heparin during CPB and as a stabilizer in neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH), a long-acting formulation of insulin.

As reported by Bakchoul et al and Lee et al, the immune response to protamine in the CPB population bears several similarities to the immune response to complexes of platelet factor 4 (PF4) and heparin, the antigenic target in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Only 1% to 3% of patients are seropositive at the time of surgery for anti-protamine1,2 or anti-PF4/heparin IgG.3 Formation of these antibodies is common after CBP, occurring in 25% to 29%1,2,4 and 39%3 of individuals, respectively, by 4 to 6 weeks. Like anti-PF4/heparin antibodies, a minority of anti-protamine antibodies induce platelet activation in vitro in a FcγRIIA-dependent manner.1,2,4

However, important differences between the anti-PF4 and anti-protamine immune response also exist. Chief among these is the nature of the antigen. PF4 is an endogenous chemokine stored in the α granules of platelets. PF4 monomers polymerize to form non–covalently-linked tetramers with a molecular weight of ∼32 kDa. Salmon protamine is a ∼4 kDa xenogeneic protein that bears scarce similarity in its linear amino acid sequence to human protamine.

The onset and persistence of antibody formation to these proteins after CPB may differ as well. Anti-PF4/heparin IgG seroconversion occurs at a median of 4 to 6 days after CPB.5 This early response suggests preimmunization to antigenic epitopes on PF4, which may reflect prior binding to the vasculature6 or certain bacteria.7 The immune response to protamine is more delayed. In the study by Lee et al, of 143 patients in whom anti-protamine IgG developed, 96% (137) seroconverted between hospital discharge and day 30 after CPB,2 a time course more consistent with a typical naïve immune response. Anti-PF4/heparin antibodies become undetectable at a median of 85 days after heparin withdrawal, although titers persist beyond 100 days in 40% of patients with HIT.8 In the study by Bakchoul et al, anti-protamine IgG was present in only 5% of patients at day >120.1 Continued exposure to an endogenous antigen (PF4) and finite exposure to a foreign protein (protamine) may underlie differences in the persistence of the immune response. Whether the immune response to protamine occurs sooner or is more persistent in NPH-treated patients with diabetes is unknown.

Heparin may also play somewhat different roles in the immune responses to PF4 and protamine. A hallmark of the immune response to PF4 is its marked augmentation by heparin. KKO is a HIT-like murine monoclonal IgG that binds to well-mapped epitopes on human PF4. At equimolar concentrations, heparin enhances KKO binding to PF4 by greater than 400-fold and promotes KKO-induced platelet activation in vitro and a HIT-like thrombotic thrombocytopenic disorder in a mouse model.9 Why is KKO binding and pathogenicity dependent on heparin? Recent studies suggest that heparin may oligomerize PF4, bringing epitopes from adjacent tetramers into apposition such that they can be recognized by single KKO molecules, thereby increasing antibody avidity (see figure, A).10,11

The effect of heparin on the immune response to protamine is less clear and may be more complex. Both Bakchoul et al and Lee et al found that heparin only modestly enhanced binding to protamine (<twofold).1,2 Importantly, in both studies, platelet activation in vitro was induced by protamine alone,1,2 a phenomenon not reported with simple addition of PF4. The addition of heparin marginally accelerated platelet activation (as measured by shortened lag time to platelet aggregation) in one study1 ; in the other study, platelet activation (as measured by 14C-serotonin release) was reduced on addition of heparin.2 These results leave uncertain the role of heparin in the immune response to protamine. It may be that heparin oligomerizes protamine and approximates some immunogenic epitopes while shielding others from antibody binding, thereby limiting its effect in vitro and in vivo (see figure, B).

Dissimilarities between the immune responses to protamine and PF4 may underlie differences in their associated disease states. HIT affects ∼1% of patients after CPB and typically presents on days 5 to 10, a median of 2 days after anti-PF4/heparin IgG seroconversion.5 If protamine-induced thrombocytopenia (PIT) exists as a clinical entity, it is likely to be rarer than HIT because of a dyssynchrony between antigen exposure (intraoperative protamine use) and antibody formation (days to weeks after CPB). An exception is patients who come to surgery with preexisting platelet-activating anti-protamine IgG, presumably because of prior CPB or NPH exposure. These patients may be at risk for severe thrombocytopenia and thrombosis in the early postoperative period, once heparin levels have decreased below those that dissociate complexes. Indeed, Bakchoul et al describe 2 participants in their cohort of 591 patients with platelet-activating anti-protamine IgG at baseline, in whom severe thrombocytopenia and arterial thromboembolism developed soon after CPB.1 There are no reports of PIT in NPH-treated diabetic patients in whom anti-protamine IgG develops after CPB. It may be that plasma concentrations of protamine achieved with NPH are sufficient to sensitize the immune system but insufficient to augment antibody binding and induce clinical disease, although this population warrants formal study.

Bakchoul et al and Lee et al have taken a critical first step by providing a description and characterization of the immune response to protamine after CPB. More work is needed to define epitopes, elucidate the role of heparin, validate clinical assays to identify patients at potential risk during CPB, and understand the clinical ramifications and management of this response. Continued comparisons with the immune response to PF4/heparin may be fruitful in addressing these questions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.