Key Points

D6 regulates the ability of lymphatic endothelial cells to discriminate between mature and immature dendritic cells.

D6 expression is regulated by inflammatory cytokines indicative of a preferential role in inflamed conditions.

Abstract

The mechanisms by which CC chemokine receptor (CCR)7 ligands are selectively presented on lymphatic endothelium in the presence of inflammatory chemokines are poorly understood. The chemokine-scavenging receptor D6 is expressed on lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) and contributes to selective presentation of CCR7 ligands by suppressing inflammatory chemokine binding to LEC surfaces. As well as preventing inappropriate inflammatory cell attachment to LECs, D6 is specifically involved in regulating the ability of LEC to discriminate between mature and immature dendritic cells (DCs). D6 overexpression reduces immature DC (iDC) adhesion to LECs, whereas D6 knockdown increases adhesion of iDCs that displace mature DCs. LEC D6 expression is regulated by growth factors, cytokines, and tumor microenvironments. In particular, interleukin-6 and interferon-γ are potent inducers, indicating a preferential role for D6 in inflamed contexts. Expression of the viral interleukin-6 homolog from Kaposi sarcoma–associated herpesvirus is also sufficient to induce significant D6 upregulation both in vitro and in vivo, and Kaposi sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma cells demonstrate high levels of D6 expression. We therefore propose that D6, which is upregulated in both inflammatory and tumor contexts, is an essential regulator of inflammatory leukocyte interactions with LECs and is required for immature/mature DC discrimination by LECs.

Introduction

Leukocyte migration is regulated by peptides belonging to the chemokine family.1 Chemokines possess variations on a conserved cysteine motif and can be divided into 4 subfamilies according to the specific nature of this motif (CC, CXC, XC, and CX3C subfamilies). Chemokines interact with target cells through receptors belonging to the 7-transmembrane-spanning family of G protein–coupled receptors,2 which are referred to as CC chemokine receptor (CCR), CXC chemokine receptor (CXCR), XCR, and CX3CR to reflect their ligand-binding specificity. Almost 50 chemokines and 19 receptors are known, and the biology of chemokines and their receptors is complicated. However, it is possible to relatively simplify chemokine biology by defining chemokines as being either homeostatic or inflammatory, according to the contexts in which they function.3,4 Homeostatic chemokines and their receptors regulate basal migration of leukocytes to and from peripheral tissues and secondary lymphoid organs. These chemokines are expressed at discrete tissue locales and by specific cell types and are generally nonresponsive to inflammatory or infectious challenge. In contrast, inflammatory chemokines and their receptors are essential for leukocyte migration to inflamed or damaged tissue sites. Accordingly, inflammatory chemokines are made in large numbers, at high concentrations, at injured or infected sites. The inflammatory chemokine/chemokine receptor system is therefore inherently less subtle than the homeostatic chemokine/chemokine receptor system.5

Although inflammatory and homeostatic chemokines play roles in different biological contexts, they work together to coordinate dendritic cell (DC)-dependent antigen presentation for initiation of adaptive immune responses. In this context, inflammatory chemokine receptor–expressing immature DCs (iDCs) are recruited to infected sites by inflammatory chemokines. Subsequent antigen exposure, in the presence of inflammatory stimuli, induces DC maturation with downregulation of inflammatory chemokine receptors and upregulation of the homeostatic receptor, CCR7.6-9 This process is essential for lymph node (LN) migration and antigen presentation by the now-mature DC (mDC). To facilitate the LN homing of CCR7+ve mDCs, the CCR7 ligand, CCL21, is selectively presented on the surface of lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) in peripheral tissues.6 Therefore, in an ongoing inflammatory response, this chemokine “receptor switching” controls the preferential lymphatic recruitment of CCR7+ve mDCs over the large number of CCR7-ve inflammatory cells; iDCs also present at inflamed sites. Importantly, this requires selective presentation of CCL21 on LEC surfaces against a background of inflammatory chemokines. Given the tendency of chemokines to bind to cell surface glycosaminoglycans,10,11 it has so far been unclear as to how the selective presentation of CCR7 ligands on LEC surfaces is achieved in such inflammatory chemokine-rich contexts.

We have been studying an atypical chemokine receptor called D612,13 that binds all inflammatory CC chemokines but not homeostatic chemokines, such as CCL21, or chemokines from any of the other subfamilies.12-15 D6 is characterized by an apparent inability to signal following ligand binding,16-19 and in vitro studies have indicated that the main role for D6 is as a chemokine-scavenging receptor that efficiently internalizes and degrades inflammatory CC chemokines.20-22 Interestingly, 1 of the primary sites of D6 expression is lymphatic endothelium.23 Recently, we demonstrated that D6-deficient mice display impaired ability to initiate adaptive immune responses.24 This is associated with aberrant inflammatory leukocyte adhesion to the lymphatic vasculature and impaired lymphatic drainage. Our hypothesis therefore is that D6 functions on LECs to ensure that the cell surface is maintained free of inflammatory CC chemokines that would lead to inappropriate adhesion of inflammatory leukocytes and iDCs, thus congesting the lymphatic system and subverting antigen presentation. In wild-type mice, therefore, D6 ensures that the only chemokines presented on lymphatic vasculature are those for CCR7; thus, only cells that have undergone switching to CCR7 positivity are able to migrate to LNs. This explains the selective presentation of CCR7 ligands, such as CCL21, on LECs in inflamed contexts. Despite these observations, we have limited insights into the precise mode of function or regulation of D6 in this context. We have shown that D6 is expressed on a subset of lymphatic vessels23 and thus it is likely that its expression is dynamically regulated. The purpose of the present study was to examine D6 biology and regulation in more detail. Here we demonstrate the ability of D6 to control inflammatory leukocyte interactions with LECs and to regulate iDC (CCR7-ve)/mDC (CCR7+ve) discrimination by LECs in a cell-autonomous manner. In addition, we report regulation of D6 by inflammatory cytokines and highlight the implications of this for the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma herpes virus (KSHV)-related neoplasms.25

Methods

Human sample use in this study was covered by ethics approval from the North Glasgow University Hospitals Division. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Cell culture, transfection, and PCR

Human iDCs (MHC-IImid/CD86mid/CD83−/CD80−/CD25-CCR7−/CCR2hi) were prepared from monocytes7,26 and matured (MHC-IIhi/CD86hi/CD83+/CD80+/CD25+/CCR7hi/CCR2lo) with LPS, prostaglandin-E2 (Sigma, Dorset, UK) and Pam3CSK4 (EMC, Germany) for 48 hours.8,27 All cytokines were from Peprotech (London, UK). Viral interleukin-6 (vIL-6) was subcloned into pEF6-TOPO (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and human dermal lymphatic endothelial cells (HDLECs; cultured as described28 ), and transfected using Amaxa-Nucleofector kit for endothelial cells (Lonza, Slough, UK). Silencer-select small interfering RNA (siRNA) (3nM) was transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). HDLECs were transduced with adenoviruses at 100 or 1000 virus particles/cell.29 RNA extraction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) were as described.26 For the analysis of vIL-6 and D6 expression, cell lines were cultured in RPMI/10% fetal calf serum/Glut plus pen/strep. CHO-K1 and CHO-745 cells30,31 were maintained in 5% CO2 in RPMI/10% fetal calf serum/4 mM glutamine with pen/strep (Invitrogen).

Adhesion assays

iDC, labeled with carboxyfluoresceinsuccinimidyl-ester and mDC with 5(6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine were seeded onto HDLEC monolayers (pretreated with 1 ng/mL tumor necrosis factor). For assays involving both iDC and mDC, 8 × 104 iDC were placed in each well and allowed to settle (30 minutes), followed by addition of 2 × 104 mDC. After 5 hours, nonadherent DCs were removed by gentle washing (phosphate-buffered saline). HDLECs and adhered DC were then detached using trypsin/EDTA and counted using FACS (MACSQuant; Miltenyi Biotec, Surrey, UK).

Immunostaining

Formalin-fixed, wax-embedded, samples were sectioned, rehydrated, and peroxidase-blocked. Antigen retrieval was in Tris/EDTA/pH 9 (30 minutes, 90°C) and sections were stained for podoplanin (rabbit anti-podoplanin, Sigma; biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG, Vector Labs, Peterborough, UK), Lyve-1 (goat anti-human; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, biotinylated anti-goat IgG, Vector Labs) and D6 (monoclonal rat anti-D6, R&D Systems; biotinylated anti-rat IgG, Vector Labs). Podoplanin and D6 were visualized in psoriatic sections using avidin-Texas-Red and avidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled secondary antibodies respectively. KS sections (from the AIDS and Cancer Specimen Bank, http://acsr.ucsf.edu) were stained as described.13

HDLECs were seeded into 24-well plates, grown until 80% confluent, then stimulated with interleukin-6 (IL-6) or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) for 6 hours or 24 hours and stained for D6 as previously described.32

Generation and expression of epitope-tagged D6 (HAD6) in CHO K1 and CHO 745 cells

D6 with an N-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag (HAD6) was cloned into pcDNA3.1 and transfected into CHO cell lines using Effectene (Qiagen, Crawley, UK) to give CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 lines. Stable transfectants were selected in 1.6 mg/mL G418 (Promega, Southampton, UK) and clones isolated by “ring-cloning” using borosilicate glass cloning-rings (SciQuip, Shropshire, UK).

Anti-D6 monoclonal antibody23,26 was biotinylated using the EZ-Link Micro-PEO4-Biotinylation Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). High D6-expressing cells were separated from low-expressing and nonexpressing cells by adding the biotinylated anti-D6 antibody to cells and mixing with Streptavidin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were run through MACS separation columns (Miltenyi Biotec) attached to a MidiMACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec) and eluates collected.

Expression of D6 was verified by flow cytometry using anti-D6 monoclonal antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled secondary antibody (R&D Systems) or alternatively biotinylated anti-HA antibody (Miltenyi Biotec) and phycoerythrin-streptavidin–labeled secondary antibody (R&D Systems).

Chemokine uptake assay with CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 clones

Alexafluor-647 labeled CCL2 (Alexa-CCL2; Almac Scotland, Edinburgh, UK) was added to CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 cells. Cells were incubated for different time periods at 37°C in 5% CO2 and subsequently washed twice in ice cold FACS buffer. DRAQ7 (BioStatus, Leicestershire, UK) was added to each cell suspension to identify non-viable cells. Fluorescence intensity of the cells was measured on a MACSquant analyzer (Miltenyi Biotec).

PCR analyses

QPCR was performed as described previously26 using RT kit Nanoscript (PrimerDesign, Southampton, UK) and SYBR Green mix Perfecta (Quanta Bioscience, Gaithersburg, MD). The following primers were used.

D6 forward: AGGAAGGATGCAGTGGTGTC

D6 reverse: CGGAGCAAGACCATGAGAAG

Tata binding protein (TBP) forward: AGGATAAGAGAGCCACGAACC

TBP reverse: TGGTCGGTGTCGTTGATG

vIL-6 forward: CAGAGGCTGAACTGGATGCT

vIL-6 reverse: TGGCGGTGTCGTTGATG

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase forward: CAAGGCTGAGAACGGGAAG

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase reverse: GGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT

HEK KSHV infection

HEK cells were cultured as previously described.12 Ninety-six–well plates were seeded with HEK cells or HEK-D6–expressing cells. Twenty-four hours later, cells were cultured in serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium and infected with KSHV-green fluorescent protein at a multiplicity of infection of 1. Cells were spun-inoculated for 25 minutes at 300g and incubated for a further 60 minutes in a 37°C heated, humidified tissue incubator. Complete media was then added and left for 24 hours. Cells were trypsinized and analyzed for green fluorescent protein expression by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using two-tailed t tests and GraphPad software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Results

D6 facilitates mature/immature DC discrimination by LECs

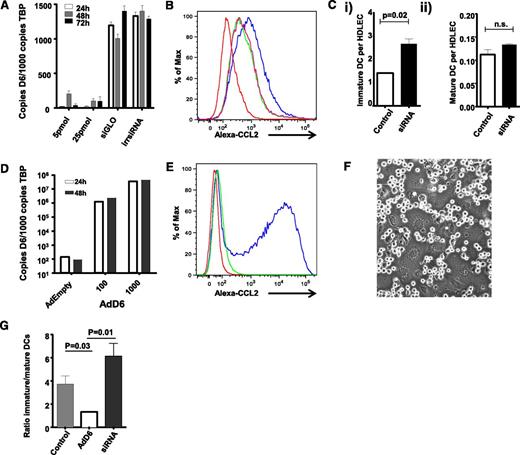

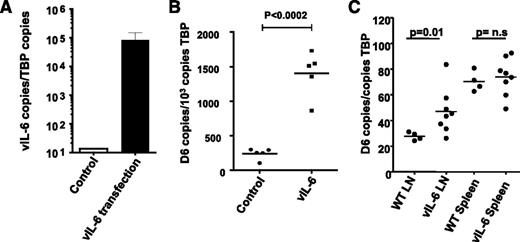

We reported D6 involvement in the selective presentation of CCR7 ligands on LEC surfaces within inflamed tissues.24 This suggests that D6 may regulate the ability of LECs to discriminate between inflammatory and immune cell types and in particular between iDC and mDC at the initiation of adaptive immune responses. Directly testing this in vivo presents a number of technological barriers; therefore, to analyze mechanisms of D6 function on LECs, we used in vitro cultured primary HDLECs.28 To test whether D6 can regulate iDC/mDC discrimination by HDLECs, we used siRNA knockdown and adenoviral overexpression strategies to generate HDLECs expressing different levels of D6. siRNA knockdown in HDLECs substantially reduced D6 transcript levels compared with control-“irrelevant” siRNA-treated cells (Figure 1A) and, importantly, decreased D6 function as shown by reduced uptake of Alexa-CCL2 (a high-affinity D6 ligand) by siRNA-treated HDLECs (Figure 1B). Next, in vitro derived iDC and mDC were incubated with control and D6-siRNA–treated HDLECs to examine the impact of D6 depletion on iDC/mDC binding. HDLECs in vitro express CCL228 and can be used to test roles for D6 in ensuring selective presentation of CCR7 ligands on HDLEC surfaces. As shown in Figure 1Ci, siRNA-mediated reduction in D6 expression was associated with a significant increase in iDC interacting with HDLEC but unaltered binding of CCR7+ve mDCs (Figure 1Cii); thus, reduced HDLEC D6 expression is associated with increased iDC binding.

D6 regulates lymphatic interactions with dCs. (A) D6 expression can be knocked down by D6-specific siRNA, but not by irrelevant siRNAs (irr siRNA) or fluorescent transfection control siRNA (siGLO), as determined by QPCR. (B) siRNA knock-down of D6 downregulates the endogenous Alexa-CCL2 uptake ability of HDLECs. Red, baseline autofluorescence of HDLECs; blue, endogenous uptake ability of control HDLECs; green/pink, repeats of D6 siRNA–treated HDLECs exposed to Alexa-CCL2. Functional D6 knockdown is represented as a “left-shift” in the flow cytometry profiles. (Ci) siRNA knockdown of D6 in HDLECs increases the number of iDC adhering (8 × 104 added) to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated HDLEC monolayers as assessed by flow cytometry. (Cii) siRNA knockdown of D6 has no effect on the number of mDC adhering (2 × 104 added) to TNF-stimulated HDLEC monolayers. (D) D6 is strongly overexpressed in HDLECs following transduction with an adenovirus expressing D6 (AdD6) vector (at 100 and 1000 viral particles/cell), as determined by QPCR. (E) AdD6 induces Alexa-CCL2 uptake. Red, baseline autofluorescence of HDLECs; green, control HDLECs treated with Alexa-CCL2; blue, adenovirus-infected HDLECs treated with Alexa-CCL2. (F) mDC and iDC compete for binding sites at HDLEC:HDLEC cell junctions. This figure visualizes unlabeled DC interacting with the underlying LEC monolayer. (G) HDLECs were either treated with siRNA to knockdown D6 or transduced with AdD6 to increase expression. Differentially dye-labeled iDC and mDC were mixed at a ratio of 4:1 (numbers as in C) and allowed to adhere to HDLEC monolayers; the relative numbers of iDC and mDC binding were assessed by FACS and expressed as an iDC/mDC ratio. All HDLECs used in the experiments represented in this figure were between passages 4 and 7.

D6 regulates lymphatic interactions with dCs. (A) D6 expression can be knocked down by D6-specific siRNA, but not by irrelevant siRNAs (irr siRNA) or fluorescent transfection control siRNA (siGLO), as determined by QPCR. (B) siRNA knock-down of D6 downregulates the endogenous Alexa-CCL2 uptake ability of HDLECs. Red, baseline autofluorescence of HDLECs; blue, endogenous uptake ability of control HDLECs; green/pink, repeats of D6 siRNA–treated HDLECs exposed to Alexa-CCL2. Functional D6 knockdown is represented as a “left-shift” in the flow cytometry profiles. (Ci) siRNA knockdown of D6 in HDLECs increases the number of iDC adhering (8 × 104 added) to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-stimulated HDLEC monolayers as assessed by flow cytometry. (Cii) siRNA knockdown of D6 has no effect on the number of mDC adhering (2 × 104 added) to TNF-stimulated HDLEC monolayers. (D) D6 is strongly overexpressed in HDLECs following transduction with an adenovirus expressing D6 (AdD6) vector (at 100 and 1000 viral particles/cell), as determined by QPCR. (E) AdD6 induces Alexa-CCL2 uptake. Red, baseline autofluorescence of HDLECs; green, control HDLECs treated with Alexa-CCL2; blue, adenovirus-infected HDLECs treated with Alexa-CCL2. (F) mDC and iDC compete for binding sites at HDLEC:HDLEC cell junctions. This figure visualizes unlabeled DC interacting with the underlying LEC monolayer. (G) HDLECs were either treated with siRNA to knockdown D6 or transduced with AdD6 to increase expression. Differentially dye-labeled iDC and mDC were mixed at a ratio of 4:1 (numbers as in C) and allowed to adhere to HDLEC monolayers; the relative numbers of iDC and mDC binding were assessed by FACS and expressed as an iDC/mDC ratio. All HDLECs used in the experiments represented in this figure were between passages 4 and 7.

Given the increased association of iDC with D6-siRNA–treated HDLECs, we next performed a reciprocal experiment to determine whether increased D6 expression could inhibit iDC interactions with HDLECs. For these experiments, a D6-expressing adenovirus construct was used to establish high-level D6 expression on HDLECs (Figure 1D) and a resultant increase in D6 function in Alexa-CCL2 uptake assays (Figure 1E). Crucially, when differentially dye-labeled iDC and mDC were mixed, applied to HDLEC monolayers, and allowed to compete for binding sites (predominantly located at cell–cell junctions: shown for unlabeled cells in Figure 1F), D6 overexpression (but not “empty” adenovirus control) enhanced HDLEC ability to discriminate in favor of mDC binding as indicated by the decreased ratio of iDC/mDC binding to HDLECs (Figure 1G). Again, siRNA-treated HDLECs demonstrated preferential binding of iDCs in this experiment, as indicated by the increased iDC/mDC ratio. Note that these ratios differ slightly from those predicted from Figure 1C, which is likely due to variations in the efficiency of DC maturation between experiments. Thus D6, in a cell-autonomous manner, can regulate the ability of HDLECs to discriminate between iDCs and mDCs.

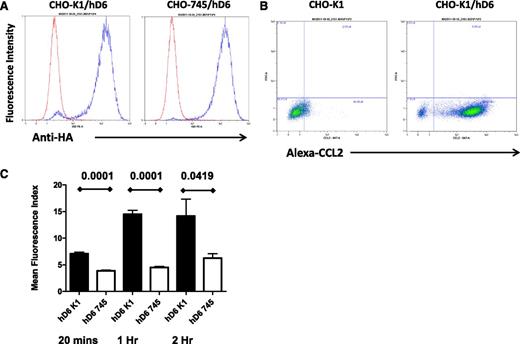

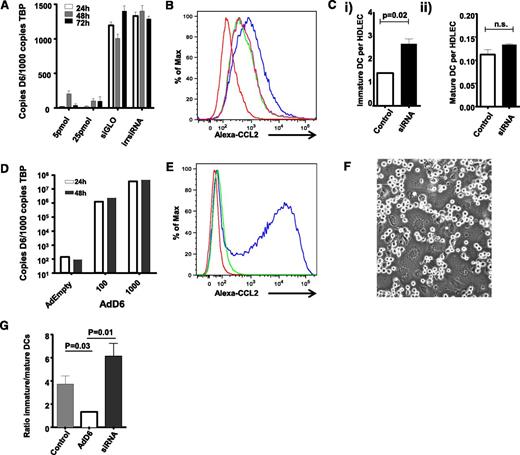

Cis-presentation of chemokines by glycosaminoglycans contributes to D6 activity

The data provided here suggest that D6 scavenges inflammatory chemokines from LEC surfaces, thereby ensuring preferential presentation of CCR7 ligands and binding of mDCs. For this to be effective in an intact lymphatic endothelium, D6 must interact with and scavenge inflammatory CC chemokines as they settle on the LEC surface. We therefore examined possible mechanisms for this with a specific focus on glycosaminoglycans, which are known binders and presenters of chemokines33,34 on endothelial cell surfaces. Given the numerous glycosaminoglycan subtypes expressed by LECs and present in associated basement-membrane structures35 and the difficulties inherent in comprehensively blocking these to examine their importance for D6 function, we opted to use CHO cells as a surrogate as well-characterized CHO cells deficient in glycosaminoglycan synthesis (CHO-745) are available for comparison with WT CHO cells (CHO-K1).30 Therefore, to determine the importance of glycosaminoglycan presentation for chemokine scavenging by D6, we generated WT (CHO-K1/hD6) and glycosaminoglycan-deficient (CHO-745/hD6)30 transfectants. Clones of CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 transfectants, with similar D6 expression levels, were identified using flow cytometry for the amino-terminal HA epitope tag (Figure 2A). Importantly, CHO-K1/hD6 cells can bind Alexa-CCL2, thus confirming the appropriateness of this model for examining the relevance of glycosaminoglycans for D6 function (Figure 2B). To directly test this, we performed a D6-dependent chemokine uptake assay using Alexa-CCL2. As shown in Figure 2C, when incubated with 15 nM Alexa-CCL2, CHO-K1/hD6 cells displayed a time-dependent increase in Alexa-CCL2 internalization that plateaued at 1 hour. In contrast, CHO-745/hD6 cells, lacking glycosaminoglycan expression, failed to significantly take up the Alexa-CCL2 at any of the time points examined. These data therefore indicate that cis-presentation of ligand by glycosaminoglycans is important for D6-dependent internalization and scavenging of inflammatory chemokines.

cis-presentation by glycosaminoglycans is important for D6 function. (A) Flow cytometry using antibodies against the N-terminal HA tag demonstrates equivalent D6 expression in the CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 clones selected for analysis. Red lines, isotype control profile; blue lines, anti-HA immunoreactivity profile. (B) FACS profiles demonstrating uptake of Alexa-CCL2 by D6-transfected CHO cells (CHO-K1/hD6) but not untransfected controls (CHO-K1). Alexa-CCL2 uptake is seen as a “right-shift” in the FACS profiles. (C) Alexa-CCL2 uptake by CHO-K1/hD6 (hD6 K1) and CHO-745/hD6 (hD6 745) transfectants at 20 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours as assessed by FACS.

cis-presentation by glycosaminoglycans is important for D6 function. (A) Flow cytometry using antibodies against the N-terminal HA tag demonstrates equivalent D6 expression in the CHO-K1/hD6 and CHO-745/hD6 clones selected for analysis. Red lines, isotype control profile; blue lines, anti-HA immunoreactivity profile. (B) FACS profiles demonstrating uptake of Alexa-CCL2 by D6-transfected CHO cells (CHO-K1/hD6) but not untransfected controls (CHO-K1). Alexa-CCL2 uptake is seen as a “right-shift” in the FACS profiles. (C) Alexa-CCL2 uptake by CHO-K1/hD6 (hD6 K1) and CHO-745/hD6 (hD6 745) transfectants at 20 minutes, 1 hour, and 2 hours as assessed by FACS.

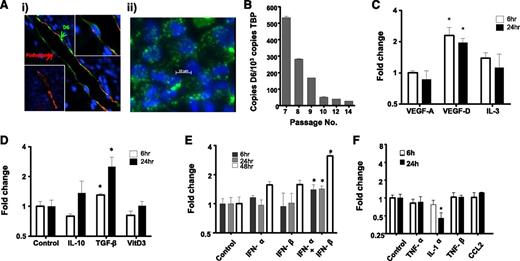

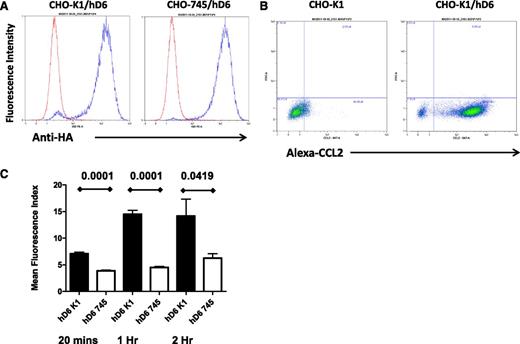

Expression of D6 by LECs is dynamically regulated

We next examined regulation of HDLEC D6 expression to determine contexts in which it may function to regulate iDC/mDC discrimination. Because D6 is likely to function predominantly in inflamed situations, we initially examined its expression pattern by immunostaining psoriatic skin as a representative human inflammatory pathology.32 This revealed varied levels of D6 expression on individual cutaneous lymphatic vessels with some being strongly positive and others lacking detectable expression (Figure 3Ai). Intriguingly, examination of the major lymphatic vessel apparent in this figure indicates that D6 expression is biased toward the luminal face of the LECs (green arrow in Figure 3Ai), suggesting that D6 may suppress inflammatory leukocyte binding to both luminal and subluminal lymphatic endothelial surfaces, in keeping with our previous results.24 Next we examined regulation of D6 expression in cultured HDLECs, which displayed a punctate D6 expression pattern (Figure 3Aii) similar to that seen in transfected cells. The vesicles present in the HDLECs are likely to correspond to the early and recycling endosomal compartment previously shown to be the major reservoir of cellular D6 protein expression.22 In keeping with the variable expression of D6 on lymphatic vessels, dynamic expression of D6 was also seen following in vitro culture of HDLECs, in that although D6 expression starts at high levels it is rapidly repressed (Figure 3B) and, following 10 passages, is near background levels. Together these observations suggest dynamic and context-dependent regulation of D6 expression on LECs.

D6 expression is dynamic and regulated by lymphangiogenic and inflammatory cytokines. (Ai) Lymphatic endothelia in human psoriatic skin stained for D6 (green) and the lymphatic marker podoplanin (red). 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) stains the nuclei. Some vessels stain strongly for D6 (top right inset), whereas others are negative for D6 expression (bottom left inset). (Aii) In vitro cultured lymphatic endothelial cells display D6 immunoreactivity (green) in punctate intracellular vesicles. DAPI (blue) stains the nuclei. (B) D6 is expressed by cultured HDLECs and is downregulated with repeat passage during continuous culture, as determined by QPCR. D6 transcript levels in HDLECs were assessed by QPCR and shown to be regulated by (C) lymphangiogenic factors, (D) anti-inflammatory cytokines, (E) type I interferons, and (F) pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines were used at the following concentrations: transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-1α (10 ng/mL); TNF-α (20 ng/mL); CCL2 (30 ng/mL); IL-3 and IL-10 (50 ng/mL); TNF-β and vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF; 100 ng/mL); vitamin D3 (10 μM); and IFN-α/β (100 μ/mL). *P < .05.

D6 expression is dynamic and regulated by lymphangiogenic and inflammatory cytokines. (Ai) Lymphatic endothelia in human psoriatic skin stained for D6 (green) and the lymphatic marker podoplanin (red). 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue) stains the nuclei. Some vessels stain strongly for D6 (top right inset), whereas others are negative for D6 expression (bottom left inset). (Aii) In vitro cultured lymphatic endothelial cells display D6 immunoreactivity (green) in punctate intracellular vesicles. DAPI (blue) stains the nuclei. (B) D6 is expressed by cultured HDLECs and is downregulated with repeat passage during continuous culture, as determined by QPCR. D6 transcript levels in HDLECs were assessed by QPCR and shown to be regulated by (C) lymphangiogenic factors, (D) anti-inflammatory cytokines, (E) type I interferons, and (F) pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokines were used at the following concentrations: transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and IL-1α (10 ng/mL); TNF-α (20 ng/mL); CCL2 (30 ng/mL); IL-3 and IL-10 (50 ng/mL); TNF-β and vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF; 100 ng/mL); vitamin D3 (10 μM); and IFN-α/β (100 μ/mL). *P < .05.

To attempt to understand this in more detail, we sought to determine factors capable of modulating D6 expression. HDLECs were stimulated with angiogenic, lymphangiogenic, anti-inflammatory, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Notably (Figure 3C), the lymphangiogenic cytokine vascular endothelial growth factor-D significantly upregulated expression in HDLECs as did the immunosuppressive cytokine transforming growth factor-β (Figure 3D). Most pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines did not modulate D6 expression although type-I IFNs significantly upregulated expression (Figure 3E) and IL-1α induced a significant downregulation (Figure 3F). Together, these data demonstrate that HDLEC D6 expression is dynamic and modulated by select cytokines with roles in lymphangiogenesis and inflammation.

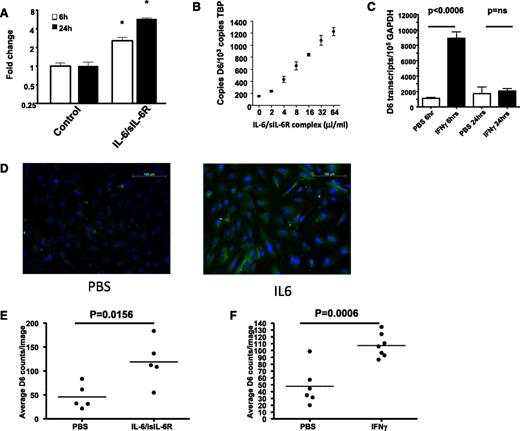

IL-6 and IFN-γ are important regulators of D6 expression

Given the importance of D6 for inflammatory responses,36-39 we further examined inflammatory cytokines for their ability to regulate D6 expression. In contrast to the relatively weak transcriptional regulation demonstrated in Figure 3, a marked effect was mediated by IL-6 (Figure 4A). In these experiments, IL-6 was applied with its soluble receptor (sIL-6R), which is required for signaling through GP130 in cells not expressing the membrane-bound IL-6 receptor.40 IL-6/sIL-6R dose-dependently upregulated D6 expression (Figure 4B). In addition, rapid and significant upregulation of D6 expression was seen following treatment of HDLECs with IFN-γ, although this was transient, with D6 levels returning to baseline by 24 hours (Figure 4C). Thus IL-6 and IFN-γ induce D6 transcription and represent the most potent regulators of D6 expression yet reported.

D6 expression is upregulated by IL-6 and IFN-γ. (A) IL-6, in concert with its soluble receptor (IL6/sIL6-R at a 1:5 molar ratio) induces significant and prolonged upregulation of D6 expression in LECs (*P < .05). (B) IL-6/sIL-6R dose dependently enhances D6 expression in LECs as assessed by QPCR. (C) IFN-γ rapidly enhances D6 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells as assessed by QPCR. (D) D6 protein expression is upregulated by 24 hours following IL-6 stimulation of LECs as demonstrated by immunostaining of IL-6 treated LEC monolayers (scale bar, 100 μm). (E-F) Quantitation of the number of D6-positive cells per field of view for IL-6– and IFN-γ–treated LECs. Note that each point represents the average of 5 field-of-view counts. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

D6 expression is upregulated by IL-6 and IFN-γ. (A) IL-6, in concert with its soluble receptor (IL6/sIL6-R at a 1:5 molar ratio) induces significant and prolonged upregulation of D6 expression in LECs (*P < .05). (B) IL-6/sIL-6R dose dependently enhances D6 expression in LECs as assessed by QPCR. (C) IFN-γ rapidly enhances D6 expression in lymphatic endothelial cells as assessed by QPCR. (D) D6 protein expression is upregulated by 24 hours following IL-6 stimulation of LECs as demonstrated by immunostaining of IL-6 treated LEC monolayers (scale bar, 100 μm). (E-F) Quantitation of the number of D6-positive cells per field of view for IL-6– and IFN-γ–treated LECs. Note that each point represents the average of 5 field-of-view counts. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

To examine the impact of the transcript upregulation on D6 protein expression, we immunostained LEC monolayers treated with phosphate-buffered saline, or the appropriate cytokine, and counted the number of D6 positive cells per field of view. Typical immunostaining results are shown for IL-6 in Figure 4D and quantified for both IL-6 and IFN-γ in Figures 4E-F. As can be seen, both IL-6 and IFN-γ induced highly significant increases in the number of D6 positive LECs, confirming concomitant upregulation of both transcript and protein in response to these factors. These results, therefore, indicate an important role for the inflammatory mediators IL-6 and IFN-γ as inducers of LEC D6 expression.

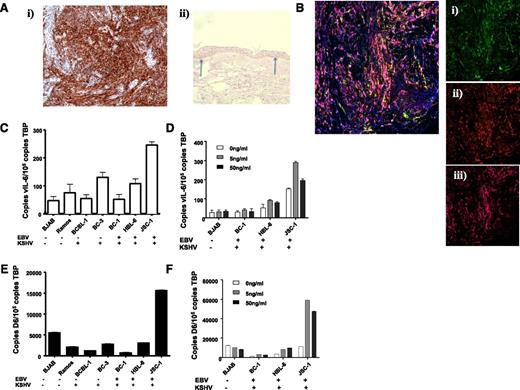

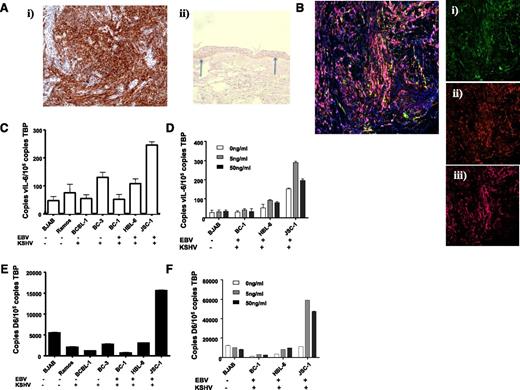

D6 is strongly expressed in KSHV-related pathologies

In addition to inflammatory contexts, the ability of IL-6 to regulate D6 expression raised the possibility of it being upregulated in pathologies associated this cytokine. Notably, KSHV, a virus that preferentially infects lymphatic endothelial-like cells giving rise to Kaposi sarcoma (KS)25 contains, within its genome, vIL-6. We therefore examined D6 expression in KS lesions. As shown in Figure 5Ai, sections from KS biopsies demonstrated strong D6 immunostaining (brown staining), and antibody specificity was confirmed by showing preferential staining of basal keratinocytes in healthy control human skin (Figure 5Aii).32 D6 staining was coincident with podoplanin and Lyve-1 (Figure 5B) indicating the lymphatic-restricted nature of the staining; thus, strong D6 expression is seen in KS.

KSHV-related pathologies display high level of D6 expression. (Ai) KS tissue samples were stained for D6 immunoreactivity. D6 positivity is represented by the brown coloration and is seen throughout the tumor mass. (Aii) Staining for D6 immunoreactivity in healthy human skin confirming the specificity of staining by the antibody (basal keratinocyte staining indicated by arrows). (B) Costaining of a KS lesion for expression of D6, Lyve1, and podoplanin. Insets show (Bi) D6 (fluorescein isothiocyanate; green), (Bii) Lyve 1 (Texas Red; red), and (Biii) podoplanin (Alexa-647; purple). Complete overlap among all 3 markers leads to a pink coloration. (C) QPCR analysis of expression of vIL-6 in control and PEL cell lines. EBV and KSHV status is indicated below the graph. (D) QPCR analysis of expression of D6 in control and PEL cell lines. Again, EBV and KSHV status is indicated below the graph. (E) QPCR analysis of vIL-6 induction by phorbol ester at the indicated concentrations of TPA. (F) QPCR analysis of D6 expression in cell lines after phorbol ester treatment at the indicated concentrations of TPA.

KSHV-related pathologies display high level of D6 expression. (Ai) KS tissue samples were stained for D6 immunoreactivity. D6 positivity is represented by the brown coloration and is seen throughout the tumor mass. (Aii) Staining for D6 immunoreactivity in healthy human skin confirming the specificity of staining by the antibody (basal keratinocyte staining indicated by arrows). (B) Costaining of a KS lesion for expression of D6, Lyve1, and podoplanin. Insets show (Bi) D6 (fluorescein isothiocyanate; green), (Bii) Lyve 1 (Texas Red; red), and (Biii) podoplanin (Alexa-647; purple). Complete overlap among all 3 markers leads to a pink coloration. (C) QPCR analysis of expression of vIL-6 in control and PEL cell lines. EBV and KSHV status is indicated below the graph. (D) QPCR analysis of expression of D6 in control and PEL cell lines. Again, EBV and KSHV status is indicated below the graph. (E) QPCR analysis of vIL-6 induction by phorbol ester at the indicated concentrations of TPA. (F) QPCR analysis of D6 expression in cell lines after phorbol ester treatment at the indicated concentrations of TPA.

KSHV is also the causative agent in other neoplasms including primary effusion lymphoma (PEL).25 Therefore, to determine whether D6 expression is associated with other KSHV-related pathologies, we obtained a variety of cell lines derived from PEL patients. Because many PEL cells are also co-infected with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV),41 we selected cell lines expressing only KSHV or expressing both EBV and KSHV. In addition, we obtained 2 B cell–derived cell lines that were not infected by either EBV or KSHV and that acted as negative controls for defining basal expression levels. To confirm active KSHV genome transcription in the PEL cell lines, we measured vIL-6 expression by QPCR. As shown in Figure 5C, the only PEL cell line displaying significant vIL-6 expression (defined as being higher than the background of nonspecific PCR product generation from the EBV and KSHV-negative BJAB and Ramos cells) was JSC-1, which also expressed markedly higher levels of D6 than any of the other cell lines (Figure 5D). Notably, there was no effect of the presence or absence of EBV on D6 or vIL-6 expression. These observations further support an association between KSHV vIL-6 and D6 expression levels. To investigate this in more detail, we took advantage of the fact that vIL-6 expression can be increased in KSHV-infected cells by treating with the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA).42 As shown in Figures 5E-F, QPCR revealed increased vIL-6 expression in 2 of the PEL cell lines in response to TPA (HBL-6 and JSC-1). Notably, in both these cell lines, especially JSC-1, a concomitant induction of D6 expression was also seen. That D6 is not upregulated by TPA in the other cell lines is in agreement with our previous demonstration of static D6 expression in the presence of TPA.36 Together, these data suggest a broad correlation between KSHV infection and D6 expression.

D6 is not a cellular entry receptor for KSHV

The data presented here suggest either that D6 is a cellular receptor for KSHV and that KSHV preferentially infects D6-positive cells or that vIL-6 upregulates D6 in KSHV-associated tumor cells perhaps to impair antitumor inflammatory responses. To test if D6 is capable of acting as a receptor for cellular entry by KSHV, we examined KSHV infection rates in HEK cells and in HEK cells transfected with D6. Results from 3 such experiments are shown in Table 1, which demonstrated no enhanced infection of D6 expressing HEK cells compared with untransfected HEK cells. These data suggest that although KS and some PEL cells express high levels of D6, this is not indicative of activity as a KSHV coreceptor.

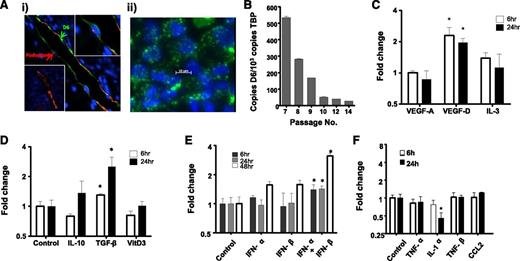

vIL-6 from KSHV upregulates D6 in LECs

To directly examine D6 induction by vIL-6 (which, in contrast to its mammalian homolog does not require the sIL-6R for signaling42 ) in LECs, we ectopically expressed vIL-6 in uninfected HDLECs by transfecting the cells with a vIL-6 expression vector, resulting in high vIL6 expression (Figure 6A). Importantly, this was associated with a highly significant increase in D6 transcription (Figure 6B), indicating the ability of vIL6 to directly induce D6 expression in HDLECs in vitro. To determine whether vIL-6 can also regulate D6 expression in vivo, LNs were obtained from vIL-6 transgenic mice43 which revealed significantly higher D6 expression than in LNs from control mice (Figure 6C). Interestingly, spleens, which lack afferent lymphatic vessels but that contain many D6-expressing leukocytes,44 did not demonstrate altered D6 expression in the vIL-6 transgenic mice (Figure 6C). Thus, although D6 appears not to be a cellular entry receptor for KSHV, it does appear to be upregulated by vIL-6 in a manner similar to that seen with human IL-6.

KSHV vIL-6 induces D6 expression in LECs. (A) Transfection of HDLECs with KSHV-encoded vIL-6 vector results in high vIL-6 expression (by QPCR). (B) Transfection with the vIL-6 vector, but not control plasmid vector, significantly upregulates D6 expression in HDLECs. (C) Transgenic expression of vIL-6 in mice under the control of the MHC-I promoter results in the overexpression of D6 in mouse lymph nodes but not spleen.

KSHV vIL-6 induces D6 expression in LECs. (A) Transfection of HDLECs with KSHV-encoded vIL-6 vector results in high vIL-6 expression (by QPCR). (B) Transfection with the vIL-6 vector, but not control plasmid vector, significantly upregulates D6 expression in HDLECs. (C) Transgenic expression of vIL-6 in mice under the control of the MHC-I promoter results in the overexpression of D6 in mouse lymph nodes but not spleen.

Discussion

Lymphatic endothelium represents the interface between innate and adaptive immune responses; this cellular barrier is essential for the selective migration of antigen-presenting cells, such as mDCs, to LNs and initiation of adaptive immune responses.6,45,46 Fundamental to this process is a selective presentation of the CCR7 ligand, CCL21, which is required to support CCR7-dependent antigen-presenting cell migration into the lymphatic system. Previously it has been unclear how the lymphatic endothelium selectively presents CCL21 within an inflamed environment where many inflammatory chemokines capable of binding to LEC surface glycosaminoglycans are also present at high concentrations. In this study, we provide evidence that the inflammatory CC-chemokine scavenging receptor D6, in conjunction with cell-surface proteoglycans, is capable of removing inflammatory CC chemokines from lymphatic endothelial surfaces on a cell-autonomous basis. This has the overall effect of enhancing the selective interaction of CCR7-expressing mDCs with the LEC surface. In this way, D6 contributes to the integration of innate and adaptive immune responses. We have shown that, in the absence of D6, lymphatic endothelial surfaces in inflamed tissues are characterized by accumulation of large numbers of inflammatory leukocytes.24 The current data provide a mechanistic explanation for this phenomenon and, although presented in the specific context of DCs, also helps explain the general lack of inflammatory cell association with lymphatic endothelium in inflamed tissues.

To provide insights into the biological contexts in which LEC D6 functions, we carried out a detailed analysis of the regulation of D6 expression in LECs. Our data demonstrate modest regulation by a range of lymphangiogenic and inflammatory cytokines, but more marked regulation by IL-6 and IFN-γ. These data suggest that LEC D6 is preferentially upregulated in response to typical proinflammatory mediators, indicating a role for D6 in inflamed contexts. Interestingly, the ability of IFN-γ to upregulate D6 expression is also seen in keratinocytes in psoriatic skin.32 It is therefore likely that a variety of cell types exposed to IFN-γ will be capable of enhancing D6 expression to either regulate interactions with inflammatory leukocytes (as with LECs) or of dampening down localized inflammatory responses (as is probably the case in psoriasis).

There is an association between D6 expression and the viral agent—KSHV—responsible for KS that preferential infects LEC-like cells and contains within its genome a viral IL-6 homolog.25,42 We now show that vIL-6 can increase D6 expression on LECs and that it is also associated with D6 expression in PEL cells. So, what possible role might vIL-6–induced D6 have in the pathogenesis of KS and PEL? One possibility is that the upregulation of D6 on tumor cells impairs the release of inflammatory CC chemokines from the tumor environment and therefore dampens inflammatory responses to the emerging cancer. In HIV patients with compromised adaptive immune responses, the innate inflammatory responses may represent the only remaining hurdle to the rapid development of KSHV-derived tumors. The ability to induce an inflammatory chemokine scavenging receptor such as D6 may therefore be an essential contributor to the emergence of these tumors. Unfortunately, KSHV mutants lacking vIL-6 are not yet available to directly test this hypothesis.

In summary, therefore, the data presented here demonstrate a clear role for D6 in ensuring the ability of lymphatic endothelium to discriminate between inflammatory chemokine receptor–expressing leukocytes and CCR7-expressing mature DCs. This has important implications for our understanding of the overall regulation of adaptive immune responses in inflamed contexts and highlights D6 as a novel contributor to this process.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Prof David Jackson and Dr Louise Johnson, The Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, for their assistance.

This work was supported by a program grant from the Medical Research Council with support from Scottish Chief Scientist's Office, Cancer Research UK, and British Heart Foundation; the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany (SFB415, project C6, SFB877, project A1), and by the Cluster-of-Excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces” (S.R.-J.); and from the University Hospitals Birmingham charity (D.J.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.H.B., R.J.B.N., and G.J.G. designed the study; C.S.M., M.D.S., K.H., O.L.-F., M.L.B., K.M.L., and R.W. performed experiments; and S.R.-J. and D.J.B. provided essential reagents.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Gerard J. Graham, Centre for Immunobiology, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, 120 University Place, Glasgow, G12 8TAUK; e-mail: gerard.graham@glasgow.ac.uk.