Key Points

CD44 expression in CLL is micromilieu instructed and promotes leukemic cell survival, which can be antagonized by CD44 antibodies.

As a surface coreceptor, CD44 supports leukemogenesis by modulating stimuli of MCL1 expression (eg, B-cell receptor signals).

The cell-surface glycoprotein CD44 is expressed in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), but its functional role in this disease is poorly characterized. We therefore investigated the contribution of CD44 to CLL in a murine disease model, the Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mouse, and in CLL patients. Surface CD44 increased during murine CLL development. CD44 expression in human CLL was induced by stimulation with interleukin 4/soluble CD40 ligand and by stroma cell contact. Engagement of CD44 by its natural ligands, hyaluronic acid or chondroitin sulfate, protected CLL cells from apoptosis, while anti-CD44 small interfering RNAs impaired tumor cell viability. Deletion of CD44 during TCL1-driven murine leukemogenesis reduced the tumor burden in peripheral blood and spleen and led to a prolonged overall survival. The leukemic cells from these CD44 knockout animals revealed lower levels of antiapoptotic MCL1, a higher propensity to apoptosis, and a diminished B-cell receptor kinase response. The inhibitory anti-CD44 antibodies IM7 and A3D8 impaired the viability of CLL cells in suspension cultures, in stroma contact models, and in vivo via MCL1 reduction and by effector caspase activation. Taken together, CD44 expression in CLL is mediated by the tumor microenvironment. As a coreceptor, CD44 promotes leukemogenesis by regulating stimuli of MCL1 expression. Moreover, CD44 can be addressed therapeutically in CLL by specific antibodies.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a paradigmatic disease for the central role of the tumor microenvironment promoting leukemic cell survival and therapy resistance. At specific sites of disease involvement (ie, peripheral blood [PB], secondary lymphoid tissues, or bone marrow), the malignant clone receives input from instructed macrophages or nurse-like cells, T cells, follicular dendritic cells, or extracellular stroma components.1 Such stimuli are mediated via cytokine, (auto)antigen, or integrin receptors and converge in the AKT, nuclear factor κB, and mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (MAPK/ERK) signaling nodes. One of the best-characterized antiapoptotic downstream effectors in CLL is the multidomain BCL2 family member MCL1.2 In CLL, MCL1 is regulated by diverse stimuli,3 but the details regarding involved receptors and upstream signaling intermediates are less well established. We previously demonstrated the relevance of the chemokine macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) for CLL development.4 Consequently, we investigated here whether one particular component of the MIF-receptor complex,5 CD44, plays a functional role in CLL.

The cell-surface glycoprotein CD44 is involved in cell motility, cellular trafficking, and stem cell differentiation.6,-8 It contributes to the phenotypic hallmarks of many cancers, such as invasiveness, self-renewal, and sustained survival.9 CD44 transmits both growth and apoptotic signals, a functional duality that is also observed in hematologic malignancies.10,,,-14 Underlying this are a prominent alternative splicing and posttranslational modifications (ie, glycosylation), making CD44 a structurally diverse and multivalent coreceptor. Signaling by its conserved intracellular domain is highly complex and incompletely understood. Context-specific input that depends, for example, on the cell’s isoform or coreceptor profile, CD44’s glycosylation status, or its ligand-complex composition, initiates corecruitment of various intermediates at defined membrane clusters (eg, receptor tyrosine kinases, ankyrin-cytoskeletal complexes, nonreceptor Src family kinases such as Lyn, or Ras-GTPases), which eventually all evoke a strong MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT response.15

The functional role of CD44 in CLL, where it is predominantly found in its standard form (CD44s) lacking all variable exons, remains poorly established. Natural-ligand–based CD44 engagement on CLL cells seems protective toward spontaneous and fludarabine-induced apoptosis, an effect that could be mimicked by stimulatory monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).16 Certain inhibitory CD44 mAbs can induce apoptosis in myeloid leukemias via ligand blocking or by alternative functional activation.17,,,,-22

Given the proposed participation of CD44 in prosurvival signaling in CLL, we wished to elucidate its functional contribution to leukemic development and its potential as a therapeutic target. Our results suggest that CD44 regulates antiapoptotic MCL1 expression via the ERK and AKT pathways. Moreover, specific anti-CD44 antibodies may be therapeutically used to interrupt survival-promoting pathways.

Methods

CLL patients

After obtaining written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Institutional Review Board–approved protocols (#11-319) at Cologne University, 60 individuals with a diagnosis of CLL based on iwCLL criteria23 provided PB samples, which were taken ≥1 month after any therapy.

Mice

Eµ-TCL1 transgenic mice24 were crossed with C57BL/6 CD44 knockout (ko) animals (CD44−/−)25 to receive F2 generations of Eµ-TCL1 mice with CD44 in wild-type (wt) “wt/wt” (Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt) or “−/−” (Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko) configuration. For determination of disease-specific overall survival (OS), Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt and Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko littermates were observed from birth until the end points of death or killing (if required by internationally endorsed principles). Hematologic screening was performed at months 3, 6, 9, and 12. Numbers of normal (CD5−) and aberrant (CD5+) B cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Experiments were approved by the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, under #9.93.2.10.31.07.097.

Murine and human sample purification and cell culture

Primary human CLL B cells and murine splenocytes were purified and cultured as described elsewhere.4,26 Healthy-donor PB mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. Their CD19+ B-cell fraction was purified by CD19 microbeads (Miltenyi). The minimum purity of CD19+ or CD5+CD19+ B cells from mice and patients was 90%. Interleukin 4 (IL-4; 20 ng/mL) and soluble CD40 ligand (CD40L; 100 ng/mL), both from PeproTech, were added as indicated. Supplemented hyaluronic acid (HA) or chondroitin sulfate (CS) were both used at 50 µg/mL (Sigma). For B-cell receptor (BCR) crosslinking, murine CLL cells were serum starved for 3 hours and stimulated with in-solution 10 µg/mL goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin M (IgM) antigen-binding fragment (SouthernBiotech) for the indicated times. For cocultures, 1 × 106 cells of the human bone marrow stroma cell (BMSC) line NKtert were prepared and 1 × 107 freshly isolated CLL primary cells added as described previously.27

Flow cytometry

Antibodies comprised anti–mouse/human CD44 (IM7) and anti–mouse CD5 (53-7.3) from Becton Dickinson; anti–mouse CD19 (6D5), anti–human CD19 (HIB19), anti–human CD45 (HI30), and anti–human immunoglobulin G1 (MOPC-21) from Biolegend; and anti–human CD5 (BL1a) and anti–human immunoglobulin G2a (7T4-1F5) from Beckman Coulter. Measurements were performed on FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) or Gallios (Beckman Coulter) cytometers. Data storage and processing was done using the Cell QuestPro (Becton Dickinson) or KALUZA (Beckman Coulter) software packages. Analytic gates refer to the CD19+ populations. Reported CD44 mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) are isotype corrected (δ-MFI).

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were prepared, separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred, and secondary HRP-labeled antibodies were applied as described previously.26 Membrane probing included the following primary antibodies: anti–mouse/human CD44 (IM7), anti–human TCL1 (1-21),26 anti–mouse MCL1 (Poly6136), and anti–BCL2 (Poly6119) from Biolegend; anti–β-actin (AC-15) from Sigma-Aldrich; anti–phospho (p)AKT (Ser473, D9E), anti-AKT (40D4), anti-pERK (Thr202/Tyr204, D13.14.4E), anti-ERK (3A7), anti-pGSK3β (Ser9, D85E12), anti-pSYK (Tyr525/526), anti-PARP (46D11), and anti–caspase-3 (8G10) from Cell Signaling Technology; and anti–human MCL1 and anti–c-MYC (N-262) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Densitometry was performed using ImageJ, including normalization to β-actin or GAPDH (or for p-proteins) to respective total protein levels.

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total splenocyte RNA was isolated (Qiagen), followed by reverse transcription and whole-transcriptome amplification, using the Quantitect Whole Transcriptome Kit (Qiagen). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) for MCL1 was run on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using Express SYBR GreenER qPCR Supermix (Invitrogen). MCL1 expression levels were normalized to peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A = PPIA). The following primers were used: mouse MCL1: forward 5′-TGTAAGGACGAAACGGGACT-3′, reverse 5′-AAAGCCAGCAGCACATTTCT-3′, mouse PPIA: forward 5′-CGCGTCTCCTTCGACCTGTTTG-3′, reverse 5′-TGTAAAGTCACCACCCTGGCACAT-3′.

Transfection of anti–human CD44 siRNA and myr-AKT

The sequences of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting human CD44 (#1: 5′-GCAAGUCUCAGGAAAUGGUGCAUUU-3′ and #2: 5′-GAGCCUGGCGCAGAUCGAUUUGAAU-3′) were generated using messenger RNA (mRNA) templates from the GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information). Sense and antisense oligonucleotides were from Invitrogen. CLL cells were electroporated with siRNAs or expression vectors of constitutively active myristoylated (myr)-AKT or controls, using the Nucleofector kit VPA-1001 (program U-013, AMAXA). For 1 × 106 cells, 3 µM anti-CD44 or scrambled control siRNA and/or 2 µg of pCDNA3.1 myr-AKT construct or empty vector were used per nucleofection. Efficiency was confirmed by an enhanced green fluorescent protein construct.

Anti-CD44 antibody treatment

The pan-isoform anti-CD44 mAb IM7 recognizing a species-conserved h-group epitope generates an apoptotic signal; this is in contrast to f-group “blocking” antibodies, which act through abrogation of HA binding.28 The anti–human CD44 clone A3D8, from immunizing human Sezary T cells, detects an unknown epitope in the CD44H (hematopoietic) cluster, which largely corresponds to CD44s.29,30 In vitro, isolated splenocytes from leukemic mice were incubated with 50 µM fludarabine, 10 µg/mL IM7, isotype control (RTK4530) antibodies (Biolegend), and respective combinations for 24 hours. Human CLL cells (as single-cell suspensions or on NKtert feeders27 ) were treated with 5 µg/mL or 10 µg/mL A3D8 or same-concentration immunoglobulin G1 isotypes (8c/6-39; Sigma Aldrich). For caspase inhibition, 25 µM or 50 µM of in-solution caspase inhibitor VI Z-VAD-FMK, a general caspase inhibitor, or 50 µM of a specific caspase 3/7 inhibitor, Z-DEVD-FMK (both from Merck Millipore), were used. In vivo, Eµ-TCL1 transgenic (tg) cells from founder #58631 were engrafted at day 20 in 8-week-old C57BL6/C3H F1 female hosts with PB CD5+19+ cells ≥5000/µL and ≥50% of all leukocytes. At this point, endotoxin-free IM7 or isotype control mAbs at 50 µg per animal were injected intravenously once or for 2 consecutive days. Pretherapeutic CLL cell counts were equally distributed across the 4 cohorts (4-5 animals per treatment arm). Postinterventional leukemic burden was determined at 24 hours and 48 hours from PB and at final postmortem exam.

Analysis of in vitro cell death and viability

The rate of apoptosis was recorded by flow cytometry for AnnexinV/7AAD (Becton Dickinson). The CaspaseGlo3/7 assay (Promega) detected caspase activity. Cell viability was evaluated by ATP content (metabolic activity) with the CellTiter-Glo assay (Promega). Luminescence was recorded on a MicroLumatPlus (EG&G Berthold) microplate luminometer (integration time: 0.1-1.0 s/well).

Immunohistochemistry and TUNEL staining

Apoptotic cells in paraffin-embedded spleen sections from leukemic mice were detected by an anti–cleaved caspase-3 antibody (Asp175; Cell Signaling Technology) and a polymer-conjugated secondary antibody with color development by FastRed (UltraVision LP Detection Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). In situ cell death detection by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) used the ApopTagPlus Kit from Merck Millipore. Images were obtained on a Pannoramic 250 Flash scanner and analyzed by Pannoramic Viewer Software (3DHISTECH). Labeled (apoptotic) cells were counted at ×40 magnification by a blinded pathologist (L.H.).

Cytomorphology

Cytospins from single-cell suspensions of isolated murine and human CLL cells were done according to routine protocols. Images were taken using an AxioScope A1 microscope (Zeiss).

Determination of IGHV mutation status

Immunoglobulin heavy chain (IGH) gene sequence analysis of murine splenocytes was done as described previously.4

Statistics

Nonparametric Mann-Whitney procedures or parametric Student’s t test estimations (both paired or nonpaired), where appropriate, were done in GraphPad Prism. Difference estimations in the cumulative survival analysis used log-rank statistics.

Results

Surface CD44 is expressed within a broad range in human CLL

CD44 surface expression on B cells from 14 normal donors and 45 CLL patients (for cohort characteristics, see supplemental Table 1) was quantified by flow cytometry with the pan-isoform mAb IM7. Recorded as isotype-controlled MFI (Figure 1A), CD44 was expressed in CD5+CD19+ CLL cells (median, 223; range, 118-453) at greater variability than in CD19+ healthy donor B cells (median, 284; range, 250-334). There were no significant differences in median CD44 MFI between ZAP70-positive vs ZAP70-negative (median/range, 249/118-418 vs 207/128-435; P = .22) or between IGHV-mutated vs IGHV-unmutated CLL (median/range, 190/156-453 vs 242/150-403; P = .57). We confirmed these findings in a comprehensive in silico meta-analysis of publically available array-derived gene expression data sets (supplemental Figure 1A and Table 2) and in comparisons of CD44 mRNA levels of healthy-donor B cells vs CLL cells by qRT-PCR (supplemental Figure 1B).

CD44 levels show a broad range in overt CLL and overexpression marks the developing malignant B-cell phenotype. (A) Surface expression of CD44 as detected by flow cytometry with the anti–pan-isoform antibody IM7 and recorded as isotype-corrected MFI in the CD19+ gate shows a markedly higher variability in 45 CLL (median, 223; range, 118-453) as compared with PB B cells from 14 healthy donors (median, 284; range, 250-334). (B) Intensity of B-cell–specific CD44 surface expression as per flow cytometry from tail vein blood increases in 3-, 6-, and 9-month-old TCL1-tg mice during evolution of CLL. Shown are medians (ranges) of isotype-corrected CD44 MFI of the CD5+CD19+ fraction at 3 months [60.0 (26.4-70.0)], 6 months [86.9 (60.9-99.1)], and 9 months [89.9 (57.3-150.3)]; data point 150.3 is not illustrated. Leukemic development is illustrated by the increasing percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells. CD44 levels do not significantly increase in the CD5-negative B-cell fraction of Eµ-TCL1 B cells. (C) Surface CD44 expression (MFI) of B cells differed significantly between splenocytes of Eµ-TCL1 mice (n = 10) at the leukemic stage (age ≥ 12 months) and their age-matched wt controls (n = 6), both within the population of CD5−CD19+ cells [median (range), 18.8 (13.5-21.6) vs 34.9 (20.9-93.6)] and of CD5+CD19+ cells (median (range), 44.9 [18.8-53.4] vs 74.7 [51.6-146.1]). (D) Immunoblots for pan-CD44 by IM7 from lysates of isolated CD19+ splenic B cells from age-matched wt (n = 2) and Eµ-TCL1 (n = 5) mice show the magnitude of differences in CD44 expression at the whole-cell level.

CD44 levels show a broad range in overt CLL and overexpression marks the developing malignant B-cell phenotype. (A) Surface expression of CD44 as detected by flow cytometry with the anti–pan-isoform antibody IM7 and recorded as isotype-corrected MFI in the CD19+ gate shows a markedly higher variability in 45 CLL (median, 223; range, 118-453) as compared with PB B cells from 14 healthy donors (median, 284; range, 250-334). (B) Intensity of B-cell–specific CD44 surface expression as per flow cytometry from tail vein blood increases in 3-, 6-, and 9-month-old TCL1-tg mice during evolution of CLL. Shown are medians (ranges) of isotype-corrected CD44 MFI of the CD5+CD19+ fraction at 3 months [60.0 (26.4-70.0)], 6 months [86.9 (60.9-99.1)], and 9 months [89.9 (57.3-150.3)]; data point 150.3 is not illustrated. Leukemic development is illustrated by the increasing percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells. CD44 levels do not significantly increase in the CD5-negative B-cell fraction of Eµ-TCL1 B cells. (C) Surface CD44 expression (MFI) of B cells differed significantly between splenocytes of Eµ-TCL1 mice (n = 10) at the leukemic stage (age ≥ 12 months) and their age-matched wt controls (n = 6), both within the population of CD5−CD19+ cells [median (range), 18.8 (13.5-21.6) vs 34.9 (20.9-93.6)] and of CD5+CD19+ cells (median (range), 44.9 [18.8-53.4] vs 74.7 [51.6-146.1]). (D) Immunoblots for pan-CD44 by IM7 from lysates of isolated CD19+ splenic B cells from age-matched wt (n = 2) and Eµ-TCL1 (n = 5) mice show the magnitude of differences in CD44 expression at the whole-cell level.

CD44 expression increases during leukemogenesis in mice

Next we performed longitudinal studies of CD44 surface expression during the emergence of leukemic B cells in Eµ-TCL1 mice.24 This was assessed in all B cells as well as in their CD19+CD5− (“normal”) and CD19+CD5+ (“aberrant”) subsets from tail vein PB at 3, 6, and 9 months of animal age (Figure 1B). At these time points, pan–B-cell median (range) CD44 MFI increased from 14.2 (11.3-20.6) over 29.0 (14.0-88.8, P = .0073) to 69.0 (40.2-145.1, P = .0003; not shown). The CD5+ B-cell fractions at these time points comprised at median 3.0%, 18.5%, and 48.0% of all TCL1-tg B cells. This expansion of aberrant B cells was also paralleled by a significant increase of their CD44 expression, especially within the first 6 months; median MFI (range) was 60.0 (26.4-70.0) at 3 months, 86.9 (60.9-99.1; P = .0044) at 6 months, and 89.9 (57.3-150.3; P = .0036) at 9 months. In contrast, the expression of CD44 in the CD5-negative B-cell fraction remained low at all of these time points (Figure 1B).

We then compared CD44 levels in splenocyte subsets of Eµ-TCL1 animals at the overt leukemic stage (age ≥ 12 months; CD5+ B cells > 50%) to age-matched C3H/C57Bl6J controls (TCL1 in wt configuration). We observed a significant CD44 upregulation in B cells of leukemic Eµ-TCL1 animals compared with their nonleukemic (TCL1wt) counterparts (Figure 1C). This was seen in both the CD5-negative (P = .001) and the CD5-positive (P = .0005) fraction of B cells, suggesting that the expression of CD44 was increased during leukemic development before the acquisition of surface CD5. Pan-CD44 immunoblot analysis via IM7 of CD19+ purified (>90%) splenocytes confirmed the CD44 upregulation in leukemic Eµ-TCL1mice (Figure 1D).

CD44 expression and receptor activation by microenvironmental stimuli promotes CLL cell survival in vitro

To explore the regulation of CD44 expression in the CLL microenvironment, we assessed how T-cell–derived cytokines32 or stromal cells27 influence CD44 expression of human CLL cells in vitro. We added soluble IL-4 and CD40L to CLL suspension cultures and also performed coculture experiments on immortalized human NKtert BMSCs.27 Under these conditions, control-normalized cell survival as per Annexin V/7AAD flow cytometry increased at day 2 by 1.20 ± 0.32-fold with IL-4/CD40L, by 1.44 ± 0.12-fold with NKtert-preconditioned supernatants, and by 1.64 ± 0.24-fold in direct CLL-NKtert BMSC feeder layer cocultures (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; all P < .05, not shown). Without any survival support, surface CD44 expression of human CLL cells diminished gradually. At day 2, CLL cells exposed to IL-4/CD40L showed a higher CD44 expression than those maintained in nonsupplemented culture media (Figure 2A). A stronger and more sustained (including day 7) increase of CD44 was observed in CLL cells exposed to preconditioned supernatants from NKtert BMSC. This was even more pronounced in CLL cells directly cocultured on NKtert feeders (Figure 2B).

CD44 promotes CLL cell survival in vitro. (A) The apoptosis-associated decrease (relative to day 0) of isotype-corrected CD44 surface expression by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 0.83 ± 0.07) in 5 human CLL samples is reversed by supplementation of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 1.17 ± 0.08; P < .05). (B) Coculture of 4 human CLL samples with the BMSC line NKtert leads to strong promotion of cell survival paralleled by increased CD44 surface expression (MFI), which is more marked in the direct feeder layer coculture (2.36 ± 0.45 at 2 days and 3.36 ± 1.20 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05) than in cultures with 2-day-old NKtert-conditioned supernatant (1.63 ± 0.27 at 2 days and 2.71 ± 1.18 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05). (C-D) The natural CD44 ligands HA and CS increase CLL cell viability and prevent apoptosis in vitro as analyzed in 19 human CLL samples. (C) A cytokine cocktail containing IL-4 and soluble CD40L consistently promotes ATP activation (mean ± SEM, 2.07 ± 0.27; P < .0001). Supplementation of media with additional HA or CS for the same 36 hours variably induces increased ATP activity and thus can synergize with the effects of IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM fold-changes to medium-only: 4.99 ± 3.91 for HA and 5.81 ± 3.77 for CS). (D) HA and CS partially prevent apoptosis (mean ± SEM fold-change to medium-only: 0.49 ± 0.09 for HA and 0.50 ± 0.10 for CS; P < .05) to a similar degree than does IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM, 0.51 ± 0.13; P < .05). (E) Double-target nucleofection experiments of scrambled/CD44 siRNAs in parallel to empty vector/complementary DNA for myr-AKT in 3 primary human CLL samples demonstrate the prosurvival relevance of CD44. CD44 knockdown decreases ATP activity (control: 2335 ± 308, CD44-siRNA: 1433 ± 328). Sole transfection of myr-AKT increases viability (4610 ± 1056), which is significantly reverted by CD44 knockdown (2134 ± 681). All values represent mean ± SEM, P < .0005, paired Student’s t test.

CD44 promotes CLL cell survival in vitro. (A) The apoptosis-associated decrease (relative to day 0) of isotype-corrected CD44 surface expression by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 0.83 ± 0.07) in 5 human CLL samples is reversed by supplementation of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 1.17 ± 0.08; P < .05). (B) Coculture of 4 human CLL samples with the BMSC line NKtert leads to strong promotion of cell survival paralleled by increased CD44 surface expression (MFI), which is more marked in the direct feeder layer coculture (2.36 ± 0.45 at 2 days and 3.36 ± 1.20 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05) than in cultures with 2-day-old NKtert-conditioned supernatant (1.63 ± 0.27 at 2 days and 2.71 ± 1.18 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05). (C-D) The natural CD44 ligands HA and CS increase CLL cell viability and prevent apoptosis in vitro as analyzed in 19 human CLL samples. (C) A cytokine cocktail containing IL-4 and soluble CD40L consistently promotes ATP activation (mean ± SEM, 2.07 ± 0.27; P < .0001). Supplementation of media with additional HA or CS for the same 36 hours variably induces increased ATP activity and thus can synergize with the effects of IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM fold-changes to medium-only: 4.99 ± 3.91 for HA and 5.81 ± 3.77 for CS). (D) HA and CS partially prevent apoptosis (mean ± SEM fold-change to medium-only: 0.49 ± 0.09 for HA and 0.50 ± 0.10 for CS; P < .05) to a similar degree than does IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM, 0.51 ± 0.13; P < .05). (E) Double-target nucleofection experiments of scrambled/CD44 siRNAs in parallel to empty vector/complementary DNA for myr-AKT in 3 primary human CLL samples demonstrate the prosurvival relevance of CD44. CD44 knockdown decreases ATP activity (control: 2335 ± 308, CD44-siRNA: 1433 ± 328). Sole transfection of myr-AKT increases viability (4610 ± 1056), which is significantly reverted by CD44 knockdown (2134 ± 681). All values represent mean ± SEM, P < .0005, paired Student’s t test.

To further evaluate the role of CD44 for CLL cell survival, we assessed the viability of CLL cells in the presence of the natural CD44 ligands HA and CS. Although, at variable degrees, HA and CS at 50 µg/mL added to the increased IL-4/CD40L–induced cellular ATP synthesis (Figure 2C), both ligands also reduced the spontaneous in vitro apoptosis of human CLL cells at 36 hours, which was of similar magnitude as mediated by the IL-4/CD40L cytokine cocktail alone (Figure 2D).

In order to substantiate the relevance of CD44 for CLL cell survival, we asked whether a reduction of CD44 expression by a siRNA-mediated knockdown would diminish CLL cell viability. Transfection efficiency based on green fluorescent protein control vectors was ∼35% to 45%. The nucleofected constructs reduced CD44 surface expression by 39% to 49% (supplemental Figure 2A). To additionally mimic a defined prosurvival stimulus without resorting to CD44-upregulating culture supplements (above), we also cotransfected CLL cells with a vector encoding constitutively active myr-AKT. AKT is an established key mediator for CLL survival and is implicated in CD44 signaling.15,33 Ectopically overexpressed myr-AKT induced elevated levels of AKT S473-phosphorylation (supplemental Figure 2B) and markedly increased ATP activity of CLL cells (Figure 2E). In contrast, CD44 knockdown reduced CLL cell viability both in AKT-untargeted and in myr-AKT–overexpressing CLL cells (Figure 2E). These data further support a functional role of CD44 for CLL cell survival.

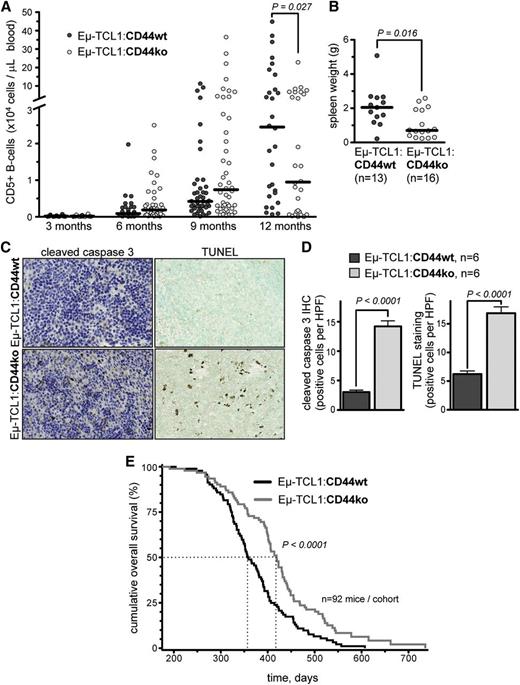

Deficiency of CD44 during murine CLL development leads to increased apoptosis, a reduced tumor load, and prolonged animal survival

To assess the role of CD44 in CLL development in an intact organism, we employed CD44 gene deletion and studied its impact on murine leukemogenesis. For that, Eµ-TCL1 mice were crossed with CD44−/− (double-allelic deficient) animals. Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt (n = 92) and Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko (n = 92) mice were followed for signs of leukemia (leukocytosis, CD5+ lymphocytosis, organomegaly) and survival. At months 3, 6, 9, and 12, there was no significant difference in absolute leukocyte count between the 2 genotypes. PB CD5+ B-lymphocyte counts tended to be higher at 3 to 9 months in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice. At 12 months, however, Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice showed significantly lower PB CD5+ B-cell counts than did Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice (median, 9481; range, 37-228 769 cells/µL vs 24 496; 653-535 108 cells/µL; P = .027; Figure 3A). TCL1wt littermates from CD44wt (n = 12) and CD44ko (n = 12) cohorts did not reveal leukocyte elevations or CD5+ B cells over a 12-month period (not shown).

CD44 deficiency mediates higher basal apoptosis and a milder presentation in murine CLL. (A) Charted are CD5+ B cells over time in the PB of Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt (black circles) and Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko (gray circles) mice. After 12 months, there is a significantly higher CD5+ B-cell count in the PB of leukemic Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice (n = 30; median, 24 496; range, 653-535 108) as compared with the Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko animals (n = 28; median, 9481; range, 37-228 769; P = .027). (B) In leukemic mice (age ≥ 12 months), spleen weights of Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt animals (n = 13; median, 2.1 g; range, 0.2-5.1 g) were significantly higher (P = .016) than in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko animals (n = 16; median, 0.7 g; range, 0.2-2.6 g). (C-D) CD44 deficiency is associated with increased apoptotic CLL cell numbers in vivo as determined in murine splenic sections by immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase-3 (left panels of C and D) and TUNEL staining (right panels of C and D). Mean ± SEM positive cells per 10 high-power fields per animal: cleaved caspase-3, Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt, 3.0 ± 0.3 vs Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko, 14.2 ± 0.9 (P < .0001); TUNEL, Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt, 6.2 ± 0.6 vs Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko 16.9 ± 1.1 (P < .0001). (E) Kaplan-Meier plots with log-rank statistics indicate a significantly prolonged leukemia-specific OS of those animals lacking CD44 expression. Median OS was 358 days for Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice vs 419 days for the Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko cohort. HPF, high-power fields.

CD44 deficiency mediates higher basal apoptosis and a milder presentation in murine CLL. (A) Charted are CD5+ B cells over time in the PB of Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt (black circles) and Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko (gray circles) mice. After 12 months, there is a significantly higher CD5+ B-cell count in the PB of leukemic Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice (n = 30; median, 24 496; range, 653-535 108) as compared with the Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko animals (n = 28; median, 9481; range, 37-228 769; P = .027). (B) In leukemic mice (age ≥ 12 months), spleen weights of Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt animals (n = 13; median, 2.1 g; range, 0.2-5.1 g) were significantly higher (P = .016) than in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko animals (n = 16; median, 0.7 g; range, 0.2-2.6 g). (C-D) CD44 deficiency is associated with increased apoptotic CLL cell numbers in vivo as determined in murine splenic sections by immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase-3 (left panels of C and D) and TUNEL staining (right panels of C and D). Mean ± SEM positive cells per 10 high-power fields per animal: cleaved caspase-3, Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt, 3.0 ± 0.3 vs Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko, 14.2 ± 0.9 (P < .0001); TUNEL, Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt, 6.2 ± 0.6 vs Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko 16.9 ± 1.1 (P < .0001). (E) Kaplan-Meier plots with log-rank statistics indicate a significantly prolonged leukemia-specific OS of those animals lacking CD44 expression. Median OS was 358 days for Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice vs 419 days for the Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko cohort. HPF, high-power fields.

To determine whether the lower leukemic PB involvement in CD44-deficient mice resulted from a reduced tumor load rather than from a compartment shift, animals of both genotypes were sacrificed at 12 months and spleen and liver weights were analyzed. Leukemic mice of both genotypes showed splenomegaly and hepatomegaly.24 However, the absence of CD44 was associated with significantly decreased spleen weights (Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt: median, 2.1 g [range, 0.2-5.1 g]; Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko: median, 0.7 g [range 0.2-2.6 g]; P = .016) (Figure 3B). The degree of hepatomegaly did not significantly differ between both groups (Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt: median, 2.66 g; Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko: median 2.52 g), nor did PB hemoglobin and platelet counts (not shown).

We proposed that these CD44-mediated phenotypic differences in murine CLL were primarily tumor-context specific rather than resulting from predetermining effects by altered B-cell physiology or BCR genetic makeup. In fact, CD44 seems dispensable for normal B-cell development;34 hence, we analyzed IGHV mutation status and gene usage from Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt vs Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice. In this limited set of cases, the BCR genetics of both phenotypes did not reveal marked differences (supplemental Table 3).

A defective apoptotic response is a hallmark of CLL. Therefore, we studied the effect of lost CD44 on spontaneous splenocyte apoptosis in leukemic animals. Spleen sections from 12-month-old animals showed a significantly higher number of cleaved caspase-3–positive and TUNEL-stained cells in the Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko genotype compared with Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt controls (both P < .0001; Figure 3C-D). A higher degree of spontaneous apoptosis was confirmed in vitro in TCL1wt:CD44ko vs TCL1wt:CD44wt splenocytes (supplemental Figure 3). Most importantly, in long-term follow-ups, the median disease-specific survival of CD44-deficient mice was significantly increased compared with CD44wt mice (358 days for Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt vs 419 days for Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko; P < .0001; Figure 3E). Postmortem pathology exam uniformly confirmed death due to leukemia.

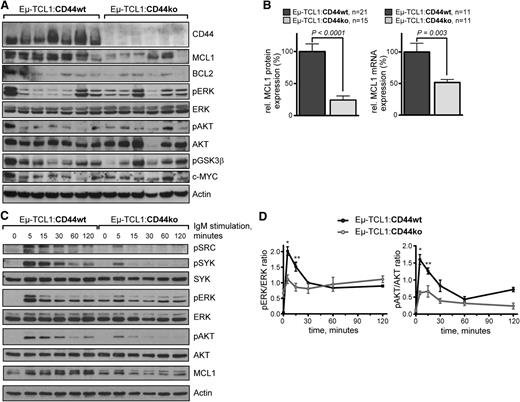

Lack of CD44 in murine leukemia is associated with reduced MCL1 levels and impaired BCR kinase response

To study the underlying molecular mechanisms of CD44-mediated survival protection in CLL, we investigated major regulators of CLL cell survival in nonstimulated, freshly isolated splenocytes from leukemic Eµ-TCL1 mice (≥12 months old) of both CD44 genotypes (Figure 4A). In immunoblots of leukemic splenocytes, MCL1 showed the most markedly reduced protein expression in CD44-deficient compared with CD44wt mice (Figure 4A-B left). This was also confirmed at the mRNA level (Figure 4B right). Interestingly, steady-state levels of major upstream inducers or stabilizers of MCL1, namely phosphoactivated kinases ERK1/2 and AKT, were not significantly altered in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko animals. We then studied the impact of altered CD44 on BCR signaling, a major trigger of MCL1. Upon IgM crosslinking, Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko splenocytes showed a delayed, less intense, and shorter phosphorylation of major BCR downstream kinases such as SRC, SYK, AKT, and ERK1/2 than did Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt splenocytes (Figure 4C-D). This was paralleled by a reduced induction of MCL1. Together, these data imply that CD44 acts in an antiapoptotic manner via modulation of MCL1 levels and functions in conjunction with BCR kinase signaling.

Lack of CD44 is associated with reduced MCL1 levels and diminished BCR kinase response. (A) A representative immunoblot of 4 independent experiments screening a panel of indicated proteins from whole splenocyte lysates (1 leukemic mouse of age ≥ 12 months per lane) shows most prominently the reduced levels of MCL1 protein in the CD44 ko genotype vs CD44 wt leukemias. (B) Left: Densitometric values of relative MCL1/Actin protein expression are charted for a larger number of animals. For better comparability across different immunoblots, means in the CD44 wt cohort are set as 100%. Mean ± SEM values were 100.0 ± 11.9 for Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt vs 24.3 ± 6.3 for Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko (P < .0001). Right: qRT-PCR from splenocyte RNA of leukemic mice (age ≥ 12 months) with MCL1 mRNA normalized to peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A = PPIA). Means in the wt cohort were set as 100%. Mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments per 11 animals per genotype show reduced MCL1 mRNA levels in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice (51.6 ± 4.8 vs 100.0 ± 13.7 in Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt; P = .003). (C) CD44 deficiency leads to diminished BCR kinase response in murine CLL cells. Splenocytes of 1 representative leukemic mouse (age ≥ 12 months) for each genotype (n = 2) were stimulated by BCR crosslinking with in-solution anti–mouse IgM antigen-binding fragment. Lack of CD44 in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko splenocytes is associated with a reduced amplitude and earlier termination of BCR-stimulated pSRC, pSYK, pERK1/2, and pAKT induction. This is associated with a much less robust MCL1 induction in BCR-activated CD44ko leukemic cells. (D) Densitometric evaluation of pERK1/2/ERK1/2 and pAKT/AKT protein from immunoblots on 3 individual splenic isolates summarizes the kinetics of the significantly reduced early BCR-induced phosphokinase response in CD44-deficient murine CLL cells. *P = .028 and P = .028 at 5 minutes and **P = .008 and P = .003 at 15 minutes for pERK1/2 and pAKT induction, respectively.

Lack of CD44 is associated with reduced MCL1 levels and diminished BCR kinase response. (A) A representative immunoblot of 4 independent experiments screening a panel of indicated proteins from whole splenocyte lysates (1 leukemic mouse of age ≥ 12 months per lane) shows most prominently the reduced levels of MCL1 protein in the CD44 ko genotype vs CD44 wt leukemias. (B) Left: Densitometric values of relative MCL1/Actin protein expression are charted for a larger number of animals. For better comparability across different immunoblots, means in the CD44 wt cohort are set as 100%. Mean ± SEM values were 100.0 ± 11.9 for Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt vs 24.3 ± 6.3 for Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko (P < .0001). Right: qRT-PCR from splenocyte RNA of leukemic mice (age ≥ 12 months) with MCL1 mRNA normalized to peptidylprolyl isomerase A (cyclophilin A = PPIA). Means in the wt cohort were set as 100%. Mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments per 11 animals per genotype show reduced MCL1 mRNA levels in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice (51.6 ± 4.8 vs 100.0 ± 13.7 in Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt; P = .003). (C) CD44 deficiency leads to diminished BCR kinase response in murine CLL cells. Splenocytes of 1 representative leukemic mouse (age ≥ 12 months) for each genotype (n = 2) were stimulated by BCR crosslinking with in-solution anti–mouse IgM antigen-binding fragment. Lack of CD44 in Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko splenocytes is associated with a reduced amplitude and earlier termination of BCR-stimulated pSRC, pSYK, pERK1/2, and pAKT induction. This is associated with a much less robust MCL1 induction in BCR-activated CD44ko leukemic cells. (D) Densitometric evaluation of pERK1/2/ERK1/2 and pAKT/AKT protein from immunoblots on 3 individual splenic isolates summarizes the kinetics of the significantly reduced early BCR-induced phosphokinase response in CD44-deficient murine CLL cells. *P = .028 and P = .028 at 5 minutes and **P = .008 and P = .003 at 15 minutes for pERK1/2 and pAKT induction, respectively.

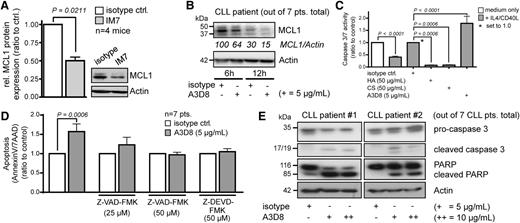

Antibody-based targeting of CD44 in CLL induces caspase-mediated cell death associated with downregulation of antiapoptotic MCL1

The data from our CD44 knockout and siRNA experiments suggested that CD44 could serve as a therapeutic target. To exploit this by antibody-based targeting, we selected the anti-CD44 mAbs IM7 and A3D8 based on their capacity to inhibit tumor propagation in other hematologic malignancies.19,22,29,30,34,35

Here, incubation with IM7 specifically reduced survival of cultured murine CLL B cells from Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt mice (Figure 5A). As reported earlier,34 the effect of IM7 was not mediated by complement-dependent cytotoxicity, since it demonstrated the same degree of apoptosis induction in serum-free conditions (not shown). The killing efficacy of IM7 in combination with fludarabine in leukemic splenocytes from Eµ-TCL1 mice was additive (Figure 5A). In concordance, exposure of 19 human CLL to concentrations of A3D8 significantly reduced cell viability (ATP activity) and induced a higher rate of apoptosis than did isotype controls (Figure 5B-C), even in the presence of IL-4/CD40L. A3D8-mediated killing appeared to be rather CLL cell specific as it was less pronounced in healthy donor B cells (supplemental Figure 4). There was no significant association of this A3D8 response with established markers of prognostic CLL subsets (eg, ZAP70 status). Treatment with 5 μg/mL A3D8 also substantially antagonized the prosurvival effect of BMSC support (NKtert cells) in 6 additional CLL patient samples (Figure 5D). Both IM7 (in TCL1-tg cells) and A3D8 (in human CLL) induced a characteristic apoptosis morphology (vacuolization, blebbing, or karyorrhexis; Figure 5E). In a pilot series of adoptive transfers of murine CLL into immunocompetent hosts, 50 µg of intravenous IM7 injected as a single dose or on 2 consecutive days significantly reduced PB leukemic growth after 24 hours and at 48 hours over the 50 µg isotype control. This was most pronounced after 2 administrations and at 24 hours postinjection (Figure 5F).

Antibody-based targeting of CD44 induces apoptosis in CLL. (A) The anti-CD44 mAb IM7 shows a specific reduction of viability by inducing cell death only in Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt splenocytes vs those from Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice (n = 10; mean ± SEM, 0.61 ± 0.06 vs 0.94 ± 0.03; P = .002). Cell death induction is increased in combination with fludarabine at 50 µM (Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt 0.35 ± 0.04, Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko 0.67 ± 0.06; P = .0012). (B) The anti-CD44 mAb A3D8 significantly reduces cell viability (ATP activity at 5 µg/mL: ratio-to-control mean ± SEM, 0.65 ± 0.08; at 10 µg/mL: 0.66 ± 0.01) and (C) induces cell death (5 µg/mL: mean ± SEM, 1.42 ± 0.10; at 10µg/mL: 1.54 ± 0.23) as compared with isotype controls in short-term (24 hours) cultures of 19 human primary CLL samples, even in the presence of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L. (D) A3D8 shows significant reduction of CLL viability in suspension cultures as well as when added for 24 hours to CLL cocultures with prosurvival NKtert stromal cell support (n = 6; mean ± SEM, isotype control 1.70 ± 0.21 vs A3D8 at 5 µg/mL 1.04 ± 0.16; P = .026). (E) Incubation of CLL cells in vitro with anti-CD44 mAbs (left: IM7 on murine Eµ-TCL1 tumor cells; right: A3D3 on human CLL cells) leads to characteristic apoptotic figures (arrows: vacuolization, blebbing, karyorrhexis). Shown are representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of a total of 3 murine and 7 human CLL after 36 hours of incubation with 5 μg/mL isotype (no signs of antibody internalization) vs 5 μg/mL CD44 mAbs. Asterisk indicates spin artifact. (F) Eight-week-old C57BL6/C3H F1 female hosts sufficiently engrafted by Eµ-TCL1 tg cells from founder #58631 were intravenously injected with endotoxin-free IM7 or isotype-control mAbs, both at 50 μg/animal, for 1 or 2 (shown here) consecutive day(s). Leukemic burden in the PB was determined before as well as 24 hours (shown here) and 48 hours after treatment. The continued leukemic growth in the isotype-treated animals (P = .0056; paired Student’s t test) was strongly inhibited by IM7 treatment (n = 4/cohort). Mean ± SEM CD19+ leukocyte counts in PB at 24 hours postinjection (“after”) were 124 ± 13 for isotype control vs 57 ± 15 for IM7 (P = .0142, unpaired Student’s t test). Postmortem (48 hours after first injection) leukemic burden in bone marrow, liver, or spleen remained unaffected (not shown).

Antibody-based targeting of CD44 induces apoptosis in CLL. (A) The anti-CD44 mAb IM7 shows a specific reduction of viability by inducing cell death only in Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt splenocytes vs those from Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko mice (n = 10; mean ± SEM, 0.61 ± 0.06 vs 0.94 ± 0.03; P = .002). Cell death induction is increased in combination with fludarabine at 50 µM (Eµ-TCL1:CD44wt 0.35 ± 0.04, Eµ-TCL1:CD44ko 0.67 ± 0.06; P = .0012). (B) The anti-CD44 mAb A3D8 significantly reduces cell viability (ATP activity at 5 µg/mL: ratio-to-control mean ± SEM, 0.65 ± 0.08; at 10 µg/mL: 0.66 ± 0.01) and (C) induces cell death (5 µg/mL: mean ± SEM, 1.42 ± 0.10; at 10µg/mL: 1.54 ± 0.23) as compared with isotype controls in short-term (24 hours) cultures of 19 human primary CLL samples, even in the presence of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L. (D) A3D8 shows significant reduction of CLL viability in suspension cultures as well as when added for 24 hours to CLL cocultures with prosurvival NKtert stromal cell support (n = 6; mean ± SEM, isotype control 1.70 ± 0.21 vs A3D8 at 5 µg/mL 1.04 ± 0.16; P = .026). (E) Incubation of CLL cells in vitro with anti-CD44 mAbs (left: IM7 on murine Eµ-TCL1 tumor cells; right: A3D3 on human CLL cells) leads to characteristic apoptotic figures (arrows: vacuolization, blebbing, karyorrhexis). Shown are representative Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins of a total of 3 murine and 7 human CLL after 36 hours of incubation with 5 μg/mL isotype (no signs of antibody internalization) vs 5 μg/mL CD44 mAbs. Asterisk indicates spin artifact. (F) Eight-week-old C57BL6/C3H F1 female hosts sufficiently engrafted by Eµ-TCL1 tg cells from founder #58631 were intravenously injected with endotoxin-free IM7 or isotype-control mAbs, both at 50 μg/animal, for 1 or 2 (shown here) consecutive day(s). Leukemic burden in the PB was determined before as well as 24 hours (shown here) and 48 hours after treatment. The continued leukemic growth in the isotype-treated animals (P = .0056; paired Student’s t test) was strongly inhibited by IM7 treatment (n = 4/cohort). Mean ± SEM CD19+ leukocyte counts in PB at 24 hours postinjection (“after”) were 124 ± 13 for isotype control vs 57 ± 15 for IM7 (P = .0142, unpaired Student’s t test). Postmortem (48 hours after first injection) leukemic burden in bone marrow, liver, or spleen remained unaffected (not shown).

In agreement with the results from the murine CD44-deficient leukemias, both anti-CD44 antibodies rapidly reduced intracellular MCL1 levels in CLL cells (Figure 6A-B). We then examined the participation of effector caspases in anti-CD44 mAb-mediated killing. As an internal control, IL-4/CD40L inhibited the increased caspase-3/7 activity, which was otherwise associated with spontaneous apoptosis of human CLL cells, by 60% (mean ± SEM, 0.40 ± 0.04). In marked contrast, a near-complete downregulation of caspase-3/7 activity was observed when adding the CD44 ligands HA and CS (mean reductions of 93% for HA and 93% for CS 93%; both P = .0006; Figure 6C). Treatment of human CLL samples with A3D8 led to a 1.8-fold increase of caspase-3/7 activity (mean ± SEM, 1.79 ± 0.30; P < .0001). A3D8-induced apoptosis was blocked by the caspase inhibitors Z-VAD-FMK and Z-DEVD-FMK (Figure 6D). Immunoblots for caspase-3 and the distal apoptotic readout poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) showed that both caspase-3 and PARP were cleaved upon treatment with A3D8 (Figure 6E).

Anti-CD44 antibodies induce cell death in CLL cells by reduction of MCL1 levels and by effector caspase activation. (A) Treatment with IM7 leads to reduction of MCL1 protein levels in murine CLL cells. Shown is a representative immunoblot of 4 independent experiments with splenocytes (isolated from TCL1 transgenic leukemic mice of age ≥ 12 months) that were treated for 24 hours in culture with 10 µg/mL IM7 or isotype control. MCL1 protein expression was quantified by densitometry and normalized to actin control. MCL1 protein in cells treated with IM7 was 0.50 ± 0.05 as compared with isotype (mean ± SEM, P = .0211). (B) Reduction of MCL1 protein levels upon A3D8 ligation in human CLL. Shown is 1 out of 7 representative cases. Numbers indicate densitometric values relative to β-actin. (C) A cocktail of IL-4/CD40L blunted increases of caspase-3/7 activity associated with spontaneous apoptosis in human CLL cells (7 cases; mean ± SEM, 0.40 ± 0.04). Caspase activity is significantly increased by the CD44-targeting clone A3D8 (mean ± SEM, 1.79 ± 0.29; P < .0001) compared with stimulation with the natural CD44 ligands HA and CS, showing mean reductions of 93% (HA) and 92% (CS) (both P = .0006) compared with A3D8-specific isotype. (D) Caspase inhibitors prevent anti-CD44–induced apoptosis (A3D8: mean 1.57 ± 0.20, dose 5 µg/mL; Z-VAD-FMK: mean 1.23 ± 0.20, dose 25 µM; Z-VAD-FMK: mean 0.97 ± 0.07, dose 50 µM; Z-DEVD-FMK: mean 1.05 ± 0.08). Incubation time was 36 hours. Plotted are mean values with SEM. (E) Cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP upon anti-CD44 ligation by A3D8 indicate induction of apoptosis. Shown are 2 exemplary cases out of 7 CLL patients.

Anti-CD44 antibodies induce cell death in CLL cells by reduction of MCL1 levels and by effector caspase activation. (A) Treatment with IM7 leads to reduction of MCL1 protein levels in murine CLL cells. Shown is a representative immunoblot of 4 independent experiments with splenocytes (isolated from TCL1 transgenic leukemic mice of age ≥ 12 months) that were treated for 24 hours in culture with 10 µg/mL IM7 or isotype control. MCL1 protein expression was quantified by densitometry and normalized to actin control. MCL1 protein in cells treated with IM7 was 0.50 ± 0.05 as compared with isotype (mean ± SEM, P = .0211). (B) Reduction of MCL1 protein levels upon A3D8 ligation in human CLL. Shown is 1 out of 7 representative cases. Numbers indicate densitometric values relative to β-actin. (C) A cocktail of IL-4/CD40L blunted increases of caspase-3/7 activity associated with spontaneous apoptosis in human CLL cells (7 cases; mean ± SEM, 0.40 ± 0.04). Caspase activity is significantly increased by the CD44-targeting clone A3D8 (mean ± SEM, 1.79 ± 0.29; P < .0001) compared with stimulation with the natural CD44 ligands HA and CS, showing mean reductions of 93% (HA) and 92% (CS) (both P = .0006) compared with A3D8-specific isotype. (D) Caspase inhibitors prevent anti-CD44–induced apoptosis (A3D8: mean 1.57 ± 0.20, dose 5 µg/mL; Z-VAD-FMK: mean 1.23 ± 0.20, dose 25 µM; Z-VAD-FMK: mean 0.97 ± 0.07, dose 50 µM; Z-DEVD-FMK: mean 1.05 ± 0.08). Incubation time was 36 hours. Plotted are mean values with SEM. (E) Cleavage of caspase 3 and PARP upon anti-CD44 ligation by A3D8 indicate induction of apoptosis. Shown are 2 exemplary cases out of 7 CLL patients.

Discussion

The adhesion molecule and glycoprotein receptor CD44 is implicated in tumor cell propagation of various cancers by mediating proliferation and dissemination.15 It is also recognized as a key marker of cancer-initiating cells in many solid tumors and in hematologic malignancies of myeloid differentiation.36,-38 Therefore, a CD44-defined niche also seems to play a pivotal role in the early steps of malignant transformation and in processes of tumor self-renewal.36 The relevance of CD44 in CLL development has not been thoroughly addressed. In particular, mechanistic insights into the role of CD44 in in vivo models of CLL were thus far not available. Consequently, we investigated here the specific contribution of CD44 in the pathogenesis of CLL by functional in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Specifically, we found that CD44 is overexpressed during evolution of CLL in the Eµ-TCL1 mouse. CD44 expression in human CLL was regulated by microenvironmental stimuli such as CD40L and IL-4, but also by stroma cell coculture. Stimulation with the known CD44 ligands HA and CS promoted the survival of CLL cells. In a CD44 knockout model of murine CLL, targeted deletion of CD44 caused a decrease in antiapoptotic MCL1 protein in leukemic cells, a higher rate of CLL cell apoptosis, a milder disease presentation with reduced tumor burden, and a longer survival of leukemic animals. In human CLL cells, CD44 reduction by siRNAs also reduced cell viability. Moreover, the BCR-triggered responses of major phosphokinases and of MCL1 levels were reduced in the leukemic CD44ko cells. Finally, the use of specific mAbs against CD44 on CLL cells induced a caspase-dependent cell death, indicating a potential therapeutic role of anti-CD44 antibodies in CLL.

As survival of CLL cells crucially depends on signals from the microenvironment,1,10 CD44 might be a central element of this tumor-promoting crosstalk. In earlier studies, CD44 was identified in a supramolecular CLL surface complex together with CD38, CD49d, and MMP-9.39,40 In our study, CD44 expression was regulated by T-cell–derived cytokines or culture on BMSC. Similarly, CLL cocultures with fibroblasts or endothelial cells have been shown to induce a CD44 upregulation along with ZAP70 overexpression.41 Furthermore, ZAP70-mediated ERK1/2 activation after BCR engagement increased CD44 expression.42 These data indicate that the very intense dialogue of CLL cells with stromal cells is mediated at least in part by CD44.

We observed here a marked variability of surface CD44 across CLL samples as compared with CD19+ PB B cells from healthy donors. However, we did not detect significant differences of CD44 levels between established prognostic CLL subgroups defined by ZAP70 or IGHV gene mutations. Published results16,43 and our in silico meta-analysis (supplemental Figure 1A and Table 2) support both of these findings. Available reports on surface vs soluble and on CD44s vs CD44v isoforms in CLL37,43,,,,,,-50 show in their entirety no clear-cut prognostic associations. However, they implicate a higher CD44 turnover in CLL over normal lymphocytes, especially in more aggressive disease subsets. Taken together, this suggests that the role of CD44 in CLL is not reflected by its mere quantitative expression.

Our in vitro and in vivo experiments of genetic CD44 targeting showed that reduced levels of CD44 led to an increased sensitivity of CLL cell apoptosis. This finding is supported by the earlier observation that CD44 activation by stimulatory antibodies led to decreased apoptosis of CLL cells in vitro.16 Our in vivo data of a strongly reduced splenic and PB leukemic burden in CD44ko variants of Eµ-TCL1 animals further support the notion that CD44 is of relevance in disease initiation or progression. Most importantly, loss of CD44 did prolong the survival of leukemic mice, indicating that this receptor promotes aggressive features of these leukemias.

Functionally, CD44 is regarded as a facultative coreceptor for several receptor complexes regulating growth, adhesion, or homing.15 In previous studies, we demonstrated the relevance of the chemokine MIF, a ligand of the CD74/CD44 complex, in CLL development.4 MIF deficiency in leukemic Eµ-TCL1 mice was associated with a phenotype of reduced tumor load and prolonged survival similar to the CD44-deficient leukemias of this study. These data suggest that the protumorigenic role of CD44 could be mediated at least in part by the MIF-receptor complex.

In the present work, we provide evidence that signaling via the BCR might be functionally regulated by CD44. Genetic loss of CD44 in murine CLL had a negative impact on the phosphoactivation response of SRC, SYK, ERK1/2, and AKT kinases to BCR stimulation. ERK1/2 and AKT represent major effectors for CD44 signaling and are important regulators of the antiapoptotic MCL1 protein in CLL.51,,-54 Accordingly, we observed decreased levels of basal and BCR-induced MCL1 in CD44-deficient leukemias, suggesting that CD44 exerts its distal antiapoptotic effects via MCL1. In line with our data are the observation that resistance to MCL1-mediated apoptosis induced by CLL–follicular dendritic cell cocultures or HA directly can be blocked by “neutralizing” anti-CD44 antibodies.53

To test for a potential therapeutic benefit of targeting CD44 in CLL, we used inhibitory anti-CD44 antibodies. The mAbs IM7 and A3D8 have been described previously and elicit a proapoptotic response in other cancer models.19,22,34,35,55 The anti–human CD44 mAb A3D8 causes apoptosis of acute myeloid leukemia cells.18,19,22,56 In our experiments, both mAbs induced MCL1 reduction and caspase-mediated cell death in murine and human CLL. Clearly, more extensive testing, addressing also the impact of soluble CD44, is needed before proceeding to clinical trials with any of these antibodies in CLL.

Overall, in extension of preliminary data implicating a relevance of CD44 in CLL,16,53 we interrogated here in detail CD44’s pathogenic role, its regulatory and downstream signals, and its target potential in this disease. We demonstrate that upregulation of CD44 on CLL cells is achieved by characteristic stimuli of the leukemic microenvironment. Furthermore, deletion or inhibition of CD44 by diverse strategies, such as gene knockout, siRNA-based targeting, and mAbs, unanimously demonstrates that CD44 is important for leukemic cell survival and the clinical aggressiveness of CLL. The antiapoptotic effects of CD44 signaling in CLL seem to be mediated by an increase of MCL1 protein expression. It is possible that this effect of CD44 results from its interactions with cytokine receptors for ligands such as MIF4 and/or with BCR signaling. Finally, specific CD44 antibodies, which are already pursued in clinical trials for other entities,57 may present a valuable addition to our current treatment options for CLL.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

Eµ-TCL1-tg breeder mice were obtained from C. Croce (Ohio State University, Columbus, OH).

The myr-AKT encoding vector and the Eµ-TCL1-tg #586 cells were kind gifts from D. Efremov (Rome, Italy). NKtert cells were obtained from J. Burger (MDACC, Houston, TX).

CLL sample acquisition was supported by the Biobank of the Center of Integrated Oncology Cologne Bonn, which is funded by the German Cancer Aid. This work was supported by The German Cancer Aid Max-Eder award (M. Herling), by a grant from The German Jose Carreras Leukemia Foundation (R09/15) (G.F.-R. and M. Herling), by start-up funds from The Köln Fortune Program (M. Herling and A.A.P-Z.), by funds from the Cluster of Excellence in Cellular Stress Responses in Aging-associated Diseases initiative (M. Hallek and M. Herling), and by grants from the German Research Foundation (grant HE-3553/2-1) (M. Herling) (grant A16 in the collaborative research consortium 832) (M. Hallek).

Authorship

Contribution: O.F., M.S., and A.A.P.-Z. designed and executed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; P.M., R.B., L.E., A.B., N.R., N.L., T.L., and M.M. designed and/or performed experiments; G.C. performed in silico data analysis; M.M.-R., L.H., and J.D. analyzed data; and M. Herling, M. Hallek, and G.F.-R. designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: G.F.-R. has been an employee of F. Hoffmann-LaRoche since 2010. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marco Herling, Cologne University, Department of Medicine I, LFI Building, Level 4, Room 105, Joseph-Stelzmann-Straße 9, 50924 Cologne, Germany; e-mail: marco.herling@uk-koeln.de.

References

Author notes

O.F., M.S., and A.A.P.-Z. contributed equally to this study, sharing first authorship.

G.F.-R. and M. Herling contributed equally to this study, sharing last authorship.

![Figure 1. CD44 levels show a broad range in overt CLL and overexpression marks the developing malignant B-cell phenotype. (A) Surface expression of CD44 as detected by flow cytometry with the anti–pan-isoform antibody IM7 and recorded as isotype-corrected MFI in the CD19+ gate shows a markedly higher variability in 45 CLL (median, 223; range, 118-453) as compared with PB B cells from 14 healthy donors (median, 284; range, 250-334). (B) Intensity of B-cell–specific CD44 surface expression as per flow cytometry from tail vein blood increases in 3-, 6-, and 9-month-old TCL1-tg mice during evolution of CLL. Shown are medians (ranges) of isotype-corrected CD44 MFI of the CD5+CD19+ fraction at 3 months [60.0 (26.4-70.0)], 6 months [86.9 (60.9-99.1)], and 9 months [89.9 (57.3-150.3)]; data point 150.3 is not illustrated. Leukemic development is illustrated by the increasing percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells. CD44 levels do not significantly increase in the CD5-negative B-cell fraction of Eµ-TCL1 B cells. (C) Surface CD44 expression (MFI) of B cells differed significantly between splenocytes of Eµ-TCL1 mice (n = 10) at the leukemic stage (age ≥ 12 months) and their age-matched wt controls (n = 6), both within the population of CD5−CD19+ cells [median (range), 18.8 (13.5-21.6) vs 34.9 (20.9-93.6)] and of CD5+CD19+ cells (median (range), 44.9 [18.8-53.4] vs 74.7 [51.6-146.1]). (D) Immunoblots for pan-CD44 by IM7 from lysates of isolated CD19+ splenic B cells from age-matched wt (n = 2) and Eµ-TCL1 (n = 5) mice show the magnitude of differences in CD44 expression at the whole-cell level.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/20/10.1182_blood-2012-11-466250/2/m_4126f1.jpeg?Expires=1769129836&Signature=stilbd6T1UDc0KOjuKSjHaOW9iMSmMVWAp47XZiZVBkhmq2Xr65Xq0NdczQYexThqQi9UEaz9R1MDTOi~xw8KTLyRo~5mH2AjPGLhBy34yzS-R0vUEzbTEO-XM2ZLKkcIEys5FSSmSKmbiupgQck7VJ0eiL1ESueqYyR2X-f0aO-JOCSUMeK0evToPyAMR9NT2Teil4P3trF4xvvy3K3LogKczl8R3QholNWJYSyI-5b01Ayfmx4RPsrqri-f0iEEewZns04uIaJPoGqagV6LELJdiAV2BFZFEZupejVImf0FGNg-dKgVvwx-mAUDCZZ1n~hIuHhzjnVpCKViyXC8g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. CD44 promotes CLL cell survival in vitro. (A) The apoptosis-associated decrease (relative to day 0) of isotype-corrected CD44 surface expression by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 0.83 ± 0.07) in 5 human CLL samples is reversed by supplementation of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 1.17 ± 0.08; P < .05). (B) Coculture of 4 human CLL samples with the BMSC line NKtert leads to strong promotion of cell survival paralleled by increased CD44 surface expression (MFI), which is more marked in the direct feeder layer coculture (2.36 ± 0.45 at 2 days and 3.36 ± 1.20 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05) than in cultures with 2-day-old NKtert-conditioned supernatant (1.63 ± 0.27 at 2 days and 2.71 ± 1.18 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05). (C-D) The natural CD44 ligands HA and CS increase CLL cell viability and prevent apoptosis in vitro as analyzed in 19 human CLL samples. (C) A cytokine cocktail containing IL-4 and soluble CD40L consistently promotes ATP activation (mean ± SEM, 2.07 ± 0.27; P < .0001). Supplementation of media with additional HA or CS for the same 36 hours variably induces increased ATP activity and thus can synergize with the effects of IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM fold-changes to medium-only: 4.99 ± 3.91 for HA and 5.81 ± 3.77 for CS). (D) HA and CS partially prevent apoptosis (mean ± SEM fold-change to medium-only: 0.49 ± 0.09 for HA and 0.50 ± 0.10 for CS; P < .05) to a similar degree than does IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM, 0.51 ± 0.13; P < .05). (E) Double-target nucleofection experiments of scrambled/CD44 siRNAs in parallel to empty vector/complementary DNA for myr-AKT in 3 primary human CLL samples demonstrate the prosurvival relevance of CD44. CD44 knockdown decreases ATP activity (control: 2335 ± 308, CD44-siRNA: 1433 ± 328). Sole transfection of myr-AKT increases viability (4610 ± 1056), which is significantly reverted by CD44 knockdown (2134 ± 681). All values represent mean ± SEM, P < .0005, paired Student’s t test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/20/10.1182_blood-2012-11-466250/2/m_4126f2.jpeg?Expires=1769129836&Signature=Fvu8YfFgUG2JFCMmYb~w6htvInLb-LF7BjES2WheymQq1HjhsSAEq33OvH4O13if8Bjmfs2zd7n1odzhdiKvFG4SfzAsK-e92imdJ5OOEpXjy~UM2Usg0LRQOKB0484aPc59kqNQ6EUdSnhyMMwPN5rN2TYb-To~37EvqCiVKG4nux9nXBIc6iTWGS4Sff9fKXAlppbbo2o-nBH1uVGsFUh~kvr9kpqNzU7Ft01QVQHcQ3QiROiRf~95sfenGzZ5TDFNz7VDzajVGhFwg8UtiACKHVmREDqq3vkRJyFKGfaERQnc8W5eY9vTYRvZxhP1v9kGmfcPXgQT0tIoURpzsA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. CD44 levels show a broad range in overt CLL and overexpression marks the developing malignant B-cell phenotype. (A) Surface expression of CD44 as detected by flow cytometry with the anti–pan-isoform antibody IM7 and recorded as isotype-corrected MFI in the CD19+ gate shows a markedly higher variability in 45 CLL (median, 223; range, 118-453) as compared with PB B cells from 14 healthy donors (median, 284; range, 250-334). (B) Intensity of B-cell–specific CD44 surface expression as per flow cytometry from tail vein blood increases in 3-, 6-, and 9-month-old TCL1-tg mice during evolution of CLL. Shown are medians (ranges) of isotype-corrected CD44 MFI of the CD5+CD19+ fraction at 3 months [60.0 (26.4-70.0)], 6 months [86.9 (60.9-99.1)], and 9 months [89.9 (57.3-150.3)]; data point 150.3 is not illustrated. Leukemic development is illustrated by the increasing percentage of CD5+CD19+ cells. CD44 levels do not significantly increase in the CD5-negative B-cell fraction of Eµ-TCL1 B cells. (C) Surface CD44 expression (MFI) of B cells differed significantly between splenocytes of Eµ-TCL1 mice (n = 10) at the leukemic stage (age ≥ 12 months) and their age-matched wt controls (n = 6), both within the population of CD5−CD19+ cells [median (range), 18.8 (13.5-21.6) vs 34.9 (20.9-93.6)] and of CD5+CD19+ cells (median (range), 44.9 [18.8-53.4] vs 74.7 [51.6-146.1]). (D) Immunoblots for pan-CD44 by IM7 from lysates of isolated CD19+ splenic B cells from age-matched wt (n = 2) and Eµ-TCL1 (n = 5) mice show the magnitude of differences in CD44 expression at the whole-cell level.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/20/10.1182_blood-2012-11-466250/2/m_4126f1.jpeg?Expires=1769176592&Signature=PZkZGNOXFHk3IC9MdF0G-TIbXXTRD9IxTGnNv7Q2WaubbL6s-uF8t4aCggSActcNNPQS1c~UbjQEqjqEqOpVIdBG~DZyyNDHtR8Td40mDujPVH4ppkTyop44TVz3xwjJJKtjESuVFjXvxHa2P5MqYi5ADTo6Jq13yICnPkPBQiyHatjO6xuu3PMQiHFji1QrC~X9jDBMIQXGjWpF19rdHjJq8pM-7j78fj-eyw1UWr40OKmvPDjrvj4F44F2xcEqMwiyTI6APwkBNbc-BaDgaV~lq3tg0sjOs9~lpxuQG8214t3PImPOXx4cOby9rTHknn95qo2Ph-jMxLjgXcrzFA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. CD44 promotes CLL cell survival in vitro. (A) The apoptosis-associated decrease (relative to day 0) of isotype-corrected CD44 surface expression by flow cytometry (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 0.83 ± 0.07) in 5 human CLL samples is reversed by supplementation of prosurvival IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM MFI at 2 days, 1.17 ± 0.08; P < .05). (B) Coculture of 4 human CLL samples with the BMSC line NKtert leads to strong promotion of cell survival paralleled by increased CD44 surface expression (MFI), which is more marked in the direct feeder layer coculture (2.36 ± 0.45 at 2 days and 3.36 ± 1.20 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05) than in cultures with 2-day-old NKtert-conditioned supernatant (1.63 ± 0.27 at 2 days and 2.71 ± 1.18 at 7 days [mean ± SEM]; P < .05). (C-D) The natural CD44 ligands HA and CS increase CLL cell viability and prevent apoptosis in vitro as analyzed in 19 human CLL samples. (C) A cytokine cocktail containing IL-4 and soluble CD40L consistently promotes ATP activation (mean ± SEM, 2.07 ± 0.27; P < .0001). Supplementation of media with additional HA or CS for the same 36 hours variably induces increased ATP activity and thus can synergize with the effects of IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM fold-changes to medium-only: 4.99 ± 3.91 for HA and 5.81 ± 3.77 for CS). (D) HA and CS partially prevent apoptosis (mean ± SEM fold-change to medium-only: 0.49 ± 0.09 for HA and 0.50 ± 0.10 for CS; P < .05) to a similar degree than does IL-4/CD40L (mean ± SEM, 0.51 ± 0.13; P < .05). (E) Double-target nucleofection experiments of scrambled/CD44 siRNAs in parallel to empty vector/complementary DNA for myr-AKT in 3 primary human CLL samples demonstrate the prosurvival relevance of CD44. CD44 knockdown decreases ATP activity (control: 2335 ± 308, CD44-siRNA: 1433 ± 328). Sole transfection of myr-AKT increases viability (4610 ± 1056), which is significantly reverted by CD44 knockdown (2134 ± 681). All values represent mean ± SEM, P < .0005, paired Student’s t test.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/121/20/10.1182_blood-2012-11-466250/2/m_4126f2.jpeg?Expires=1769176592&Signature=eTcbkc~rZTIxXnFNfRE~2sz-Vn0Gn~3lWqfkkASLZ77hnBLKvZniGFbFEyypmO~gp4Zn3alSNjwtzygZOeVU4ihKHFhvr9PCPlmDv8w9c6iC5aWyAJIKsgPL~fP6vpIY7TECGM5gjS9WY4bsM8VyMlyc-U1SqkVLaEXxMkNp11erZWARqyFvZ61rBR8LhDwTA6wG88XQ5WwG3gE4avOHYRp~kI50pdBVuJny49gbqb~V1qitTD5WrUe25zMqhNWv-aqJ1zW1kRhkxX3-zc2FVRlTRKbSNBUgpSXXz7Rf5DhZC7DFQhKS26mkSb3AJvQ-OB-s1PKDn-rnCVwLiAczKg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)