Abstract

The two most commonly accepted approaches for limited stage, non-bulky diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)—an abbreviated course of chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) with radiation (RT) or an extended course of CIT alone—are largely based on studies performed prior to the widespread use of rituximab. Little is known about the comparative effectiveness of these treatment approaches, especially for the elderly.

We conducted a retrospective analysis using the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare). Patients > 65 years of age diagnosed with stage I or II DLBCL between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2009 were eligible. Patients who received RT prior to CIT or 6 to 8 cycles of CIT plus RT were excluded, as we considered these to be surrogates for bulky disease. We characterized the prevalence and covariates of treatment types initiated within 180 days of diagnosis: standard treatment (3 to 4 cycles of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone [RCHOP] plus RT or 6 to 8 cycles of RCHOP), nonstandard treatment (any therapy except standard treatment), and no treatment. We also characterized disability status, defined as “poor” if there were any claims for mobility aids, oxygen therapy supplies, home care services or skilled nursing facility admissions in the 12 months prior to diagnosis. Next, using propensity-score weighted Cox regression models that included available sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (see Table), we compared treatment-free (TFS) and overall survival (OS) for patients who received one of the two standard treatments. TFS was defined as freedom from one of two events: evidence of subsequent treatment (any new claim for chemotherapy occurring > 90 days after the completion of initial therapy) or death. We also assessed the odds of hospitalization and of developing poor disability status in the year following therapy for both standard treatments.

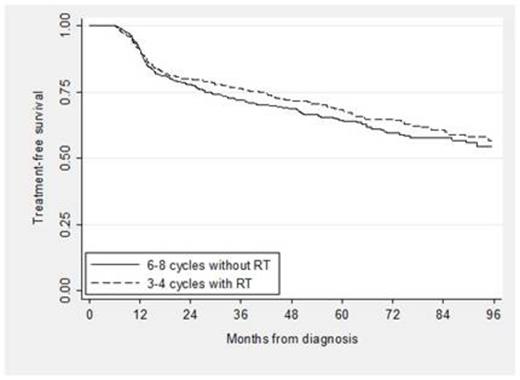

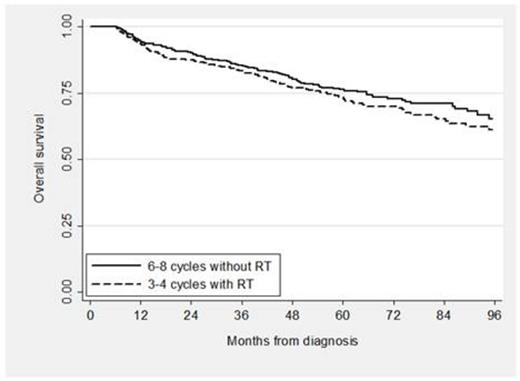

A total of 4,035 patients were eligible: 24% received standard treatment, 66% received nonstandard treatment and 10% received no treatment. Among the patients with nonstandard treatment, 13% received RT alone, 26% received < 6 cycles of RCHOP and no RT, 9% received 1, 2 or 5 cycles of RCHOP plus RT, and 52% received therapy other than RCHOP. Of those who received standard treatment, 439 received 3 to 4 cycles of RCHOP plus RT and 530 received 6 to 8 cycles of RCHOP. Characteristics of the standard treatment groups are shown below (see Table). In the propensity score analysis, TFS and OS for patients who received abbreviated CIT plus RT compared to an extended course of CIT alone were not significantly different (see Figure 1; propensity score adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for TFS 0.90, 95% CI [0.72, 1.12], p = 0.33; HR for OS 1.18, 95% CI [0.92, 1.53], p = 0.19). In addition, the odds of hospitalization was not different for patients who received abbreviated CIT plus RT compared to extended CIT (OR 0.90, 95% CI [0.70, 1.16], p = 0.43) and neither were the odds of developing poor disability status (OR 1.37, 95% CI [0.97, 1.94], p = 0.10).

In this large cohort of elderly patients with a potentially curable disease, a significant proportion received non-standard therapy or no treatment at all. For those able to complete standard treatment, there was no difference in TFS or OS comparing 3 to 4 cycles of RCHOP plus RT with 6 to 8 cycles of RCHOP, confirming clinical trial findings from the pre-rituximab era. Moreover, the lack of differences in subsequent hospitalizations or changes in disability status suggests similar tolerability, and thus similar effectiveness of both treatments.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.