Abstract

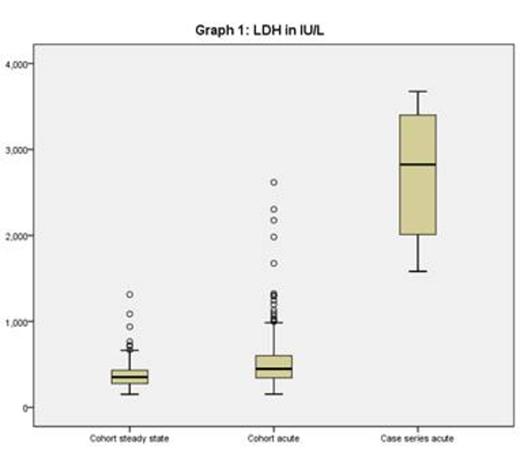

Recurrent vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) is a hallmark of sickle cell disease (SCD). Its pathobiology remains poorly understood. VOC occurs on a background of chronic haemolysis with lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a key biomarker. In steady state, patients have elevated total LDH which becomes more elevated in VOC. Recent data from King's College Hospital (2009-10) shows LDH in VOC was significantly increased by 28% compared to steady state, from 379 +/- 155 IU/L in steady state to 507+/-272 IU/L in VOC. In the same population, platelet counts remained similar in VOC and steady state (363 +/-177x109/L versus 379+/-161x109/L, respectively).

Recent analysis has identified LDH as the best bio-predictor of the clinical trajectory of a VOC; severity of VOC appears to correlate with the rise in LDH. A putative mechanism has been suggested after LDH levels were found to be proportional to total activated von Willebrand's Factor (VWF), suggesting that acute SCD may represent a haemolytic microangiopathy on the thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) spectrum. LDH is composed of five isoforms; it has been suggested that some of the increased LDH may be of non-red cell origin, for example bone marrow necrosis.

On a retrospective review of our medical records (2006-2013), we identified 12 admissions in 12 different patients with both strikingly elevated LDH (> 1500IU/L) AND thrombocytopenia (platelets <150 x109/L). Laboratory values for the King's cohort in steady state, in acute admissions and for the case series are in graphs 1 (LDH) and 2 (platelets).

The patient characteristics are summarised in table 1. The average age on admission was 29.5 years (+/-10.5 years), 9 patients were male, and included 10 HbSS and 2 HbSC. The clinical phenotypes varied from minimal sickle problems to major co-morbidities. Five patients had frequent hospital admissions (>2/year) due to VOC. All other hospital admissions for these same patients were accompanied by mild elevations in LDH. One patient was on hydroxyurea and two patients were on regular exchange transfusion programmes.

Except for patient 3, all the patients had a similar presentation: admission with acute pain, some with a fever, with typical VOC admission bloods i.e. mild Hb decrease, mild LDH increase, and platelets similar to steady state. In the subsequent 2-3 days, patients became more unwell, and hyper-acutely developed both a strikingly elevated LDH, and a synchronous drop in platelet count. Four patients had an associated Hb drop that required blood transfusion. One was red cell exchanged for acute chest syndrome (ACS). Two patients (4, 9) had ADAMTS13 confirmed as low, although not low enough for TTP itself to be diagnosed; they were plasma exchanged. Two patients had bone infarction identified radiologically. The outcome was poor in two of twelve cases: one patient died, and another suffered cauda equina syndrome.

For all patients, these episodes represented an extraordinary VOC admission suggesting a separate, unpredictable severe acute phenomenon rather than a typical VOC event. A super elevated LDH together with thrombocytopenia appears to represent a distinct and rare acute sickle phenomenon. Considering it on the TTP spectrum may yield further clues to its underlying pathobiology, although significant bone infarction may also contribute. Interpreting an elevated LDH is not biologically simple, but its clinical utility is undisputed. We suggest using a super elevated LDH concomitant with thrombocytopenia to identify patients potentially at risk of unusually severe VOC, and to consider pre-emptive strategies (e.g. transfusion) early in these cases.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

patient characteristics

| Pt . | Genotype . | Age . | Gender . | Admission diagnosis . | Steady state . | Admission . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb . | Plts . | LDH . | Hb . | Plts . | LDH . | |||||

| 1 | HbSS | 19 | m | ACS | 9.9 | 580 | 405 | 6.5 | 39 | 2486 |

| 2 | HbSS | 48 | f | ACS | 7.8 | 509 | 373 | 4.5 | 129 | 2035 |

| 3 | HbSS | 36 | f | Ruptured ovarian abscess | 7.6 | 542 | 355 | 7.3 | 88 | 1582 |

| 4 | HbSS | 38 | m | TTP like syndrome | 7.6 | 280 | 384 | 5.7 | 25 | 1922 |

| 5 | HbSS | 27 | m | ACS | 10.8 | 361 | 302 | 8.6 | 56 | 3385 |

| 6 | HbSS | 19 | m | Pain crisis | 9.9 | 353 | 191 | 5.7 | 89 | 1985 |

| 7 | HbSC | 48 | f | Multi-organ failure | 12.2 | 188 | 260 | 7.5 | 21 | 3414 |

| 8 | HbSS | 26 | m | Lumbar-sacral infarcts with CES | 9.8 | 570 | 315 | 7.4 | 107 | 3200 |

| 9 | HbSS | 25 | m | TTP like syndrome | 10.1 | 254 | 305 | 6.5 | 21 | 3647 |

| 10 | HbSS | 22 | m | ACS | 8.4 | 330 | 411 | 6.9 | 117 | 2286 |

| 11 | HbSS | 19 | m | Extra-dural and extra-cranial haematomas, bone infarction | 11.9 | 353 | 403 | 5.4 | 75 | 3675 |

| 12 | HbSC | 28 | m | Encephalitis | 12.8 | 326 | 317 | 9.1 | 60 | 3165 |

| Pt . | Genotype . | Age . | Gender . | Admission diagnosis . | Steady state . | Admission . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb . | Plts . | LDH . | Hb . | Plts . | LDH . | |||||

| 1 | HbSS | 19 | m | ACS | 9.9 | 580 | 405 | 6.5 | 39 | 2486 |

| 2 | HbSS | 48 | f | ACS | 7.8 | 509 | 373 | 4.5 | 129 | 2035 |

| 3 | HbSS | 36 | f | Ruptured ovarian abscess | 7.6 | 542 | 355 | 7.3 | 88 | 1582 |

| 4 | HbSS | 38 | m | TTP like syndrome | 7.6 | 280 | 384 | 5.7 | 25 | 1922 |

| 5 | HbSS | 27 | m | ACS | 10.8 | 361 | 302 | 8.6 | 56 | 3385 |

| 6 | HbSS | 19 | m | Pain crisis | 9.9 | 353 | 191 | 5.7 | 89 | 1985 |

| 7 | HbSC | 48 | f | Multi-organ failure | 12.2 | 188 | 260 | 7.5 | 21 | 3414 |

| 8 | HbSS | 26 | m | Lumbar-sacral infarcts with CES | 9.8 | 570 | 315 | 7.4 | 107 | 3200 |

| 9 | HbSS | 25 | m | TTP like syndrome | 10.1 | 254 | 305 | 6.5 | 21 | 3647 |

| 10 | HbSS | 22 | m | ACS | 8.4 | 330 | 411 | 6.9 | 117 | 2286 |

| 11 | HbSS | 19 | m | Extra-dural and extra-cranial haematomas, bone infarction | 11.9 | 353 | 403 | 5.4 | 75 | 3675 |

| 12 | HbSC | 28 | m | Encephalitis | 12.8 | 326 | 317 | 9.1 | 60 | 3165 |

ACS – acute chest syndrome, AVN – avascular necrosis, TTP – thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.