Abstract

ASXL1 gene mutations and IDH1/IDH2 mutations were described in Ph-negative MPN in 2009 and 2010, respectively. We aimed to study frequency of aferomentioned mutations and their clinical importance, prevelance and potential prognostic significance in Ph-negative MPN.

Study group consisted of 107 ET (58 females, 49 males) and 77 PMF (43 females, 34 males) patients diagnosed according to WHO 2008 criteria. Exon 12 of ASXL1 was amplified from genomic DNA and bidirectionally sequenced. High-resolution melting was performed for IDH1 mutations (R130) and IDH2 mutations (R140 and 172) followed by confirmatory bidirectional sequence analysis. To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of ET studying ASXL1 mutations.

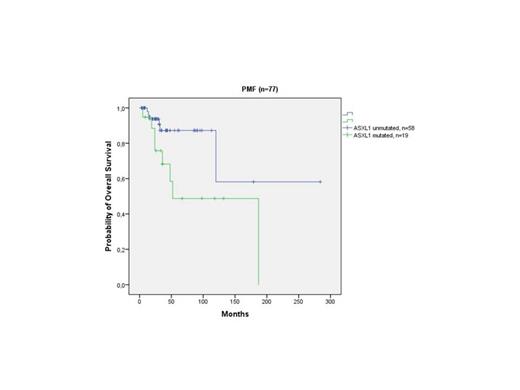

Frequency of ASXL1 mutations (exon 12) was significantly higher in PMF (24.7%) compared to ET patients (8.4%; p=0.005). Our analysis identified 29 different mutations of ASXL1 in 28 out of a total 184 patients, (15.2%) (one PMF patient presented with two simultaneous mutations). Nonsense mutations, including frameshift mutations were detected in 19 patients (10.3%). Mutant IDH was detected in 2 ET (1 IDH1 R140Q, 1 IDH1 R132C) and 5 PMF patients (3 IDH1 R123C, 1 IDH1 R132S, 1 IDH2 R140Q). The ET patient with IDH2 mutation (R140Q) harbored JAK2V617F mutation with an allele burden of 5% while the other patient with IDH1 mutation (R132C) did not harbor JAK2V617F mutation. 3 of 5 IDH mutated PMF patients (1 IDH1 R132C, 1 IDH1 R132S and 1 R140Q) concurrently carried JAK2V617F mutation with an allel burden of 31-50%, 5-12.5% and 31-50%, respectively. Frequency of IDH mutation for ET and PMF patients was 1.9% and 6.5%, respectively (p=0.131). We observed shortened OS in ASXL1-mutated PMF patients as compared to ASXL1 wild-type PMF patients(mean 108 months; 95% CI: 62-153 and 202 months; 95% CI: 123-282, respectively; p=0.025). (Figure 1). Also, trend towards shorter OS was observed in presence of ASXL1 nonsense sequence variations with respect to other sequence variations (p=0.09). Multivariate survival analysis confirmed independent prognostic value of ASXL1 mutations (OR: 2.75; 95% CI:1.37-5.5; p=0.033) but not ASXL1 nonsense sequence variations (p=0.131). Although number of IDH mutated PMF patients was small, we observed significantly shorter LFS in IDH mutated patients as compared to IDH wild-type patients (p=0.024).

Survival analysis of PMF patients according to the ASXL1 mutational status.

In our study group, 7% of JAK2V617F-negative ET and 26.3% of JAK2V617F-negative PMF patients showed ASXL1 mutations. Based on our findings, it may be deduced that analysis of ASXL1 genes provided an additional 7% increase in ET and a 26.3% increase in PMF patients with a detected molecular marker of clonality. In our relatively large cohort of PMF patients, ASXL1 and IDH mutations were associated with shortened OS and LFS, respectively. One of 5 IDH mutated PMF patients harboring IDH mutations showed leukemic transformation. Thus, it can be suggested that IDH mutations may play a role in prediction of leukemic transformation. ASXL1 mutated PMF patients did not show an increase in poor karyotype features. In PMF, death and bleeding complications were associated with combined ASXL1 and IDH mutations. Additional studies are needed to clearly assess impact of mutation combinations on disease course and severity. An important characteristic feature of IDH mutated PMF in this study was the paucity of abnormal or unfavorable karyotype. All IDH mutated PMF patients had normal karyotype. Thus, it seems that ASXL1 mutations and IDH mutations represent independent prognostic biomarkers in PMF. Our findings support previous observations that mutations affecting epigenetic regulation might be prognostically more relevant than those involving JAK-STAT signaling in PMF.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.