Key Points

Activation of endothelial cells by anti-β2GPI antibodies causes myosin RLC phosphorylation, leading to actin-myosin association.

In response to anti-β2GPI antibodies, release of endothelial microparticles, but not E-selectin expression, requires actomyosin assembly.

Abstract

The antiphospholipid syndrome is characterized by thrombosis and recurrent fetal loss in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs). Most pathogenic APLAs are directed against β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), a plasma phospholipid binding protein. One mechanism by which circulating antiphospholipid/anti-β2GPI antibodies may promote thrombosis is by inducing the release of procoagulant microparticles from endothelial cells. However, there is no information available concerning the mechanisms by which anti-β2GPI antibodies induce microparticle release. In seeking to identify proteins phosphorylated during anti-β2GPI antibody-induced endothelial activation, we observed phosphorylation of nonmuscle myosin II regulatory light chain (RLC), which regulates cytoskeletal assembly. In parallel, we observed a dramatic increase in the formation of filamentous actin, a two- to fivefold increase in the release of endothelial cell microparticles, and a 10- to 15-fold increase in the expression of E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, and tissue factor messenger RNA. Microparticle release, but not endothelial cell surface E-selectin expression, was blocked by inhibiting RLC phosphorylation or nonmuscle myosin II motor activity. These results suggest that distinct pathways, some of which mediate cytoskeletal assembly, regulate the endothelial cell response to anti-β2GPI antibodies. Inhibition of nonmuscle myosin II activation may provide a novel approach for inhibiting microparticle release by endothelial cells in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies.

Introduction

The antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is characterized by venous or arterial thrombosis and recurrent fetal loss associated with persistently positive test results for antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs).1-4 Most pathogenic APLAs are directed against phospholipid binding proteins, the most common of which is β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI).5-8 β2GPI is a 5-domain protein that binds to endothelial cells or phospholipid via lysine-rich regions in domain 5.9 Crosslinking of cell-bound β2GPI by anti-β2GPI antibodies that bind domain 17 induces cellular activation through receptors such as annexin A210,11 or apoER2.12,13 Endothelial cell activation by anti-β2GPI antibodies is thought to play an important role in the development of thrombosis,1,14 although these antibodies also inhibit key anticoagulant processes such as the activation and activity of protein C15 and the formation of an annexin A5 antithrombotic shield.16

The mechanisms underlying endothelial cell activation by anti-β2GPI antibodies have been the focus of intensive research. Activation occurs in a β2GPI-dependent manner11,17,18 and is mediated via pathways that involve activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB),19 extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK 1/2), and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase.20 Activation of endothelial cells leads to increased expression of adhesion molecules17,21 and inflammatory cytokines22 as well as procoagulant activity23 and the release of microparticles.24

Microparticles are cell-derived vesicles <1 µM in size that arise from a number of cell types in response to activation or apoptosis.25 Most microparticles express anionic phospholipid,26 providing a site for assembly of coagulation complexes and tissue factor.27 Elevated levels of microparticles circulate in patients with several vascular disorders24,28 and may be associated with thrombosis.29 Microparticles may also contribute to (patho)physiological processes through other mechanisms, such as transfer of cellular receptors and nucleic acids.26,30

Compared with the many descriptions of circulating microparticles in patients with clinical disorders, there is little information concerning the mechanisms of microparticle formation in response to disease-inducing stimuli.31 Because elevated levels of microparticles have been detected in patients with APS, a disorder thought to result in part from endothelial activation, we assessed the cellular mechanisms underlying microparticle release by anti-β2GPI antibodies.

Materials and methods

Materials

These studies were approved by the institutional review board of the Cleveland Clinic and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Human β2GPI was purified from fresh-frozen plasma.11 Anti-β2GPI antibodies were affinity purified from rabbits immunized with human β2GPI and from 3 patients with APS using β2GPI conjugated to Affigel HZ (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA)11 ; purity of the affinity-purified antibodies was confirmed by reduced sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Goat anti–human E-selectin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated rabbit anti-mouse and rabbit anti-goat secondary antibodies and purified C1q were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and control rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) was from Zymed (South San Francisco, CA). Phycoerythrin (PE)-IgG and anti-CD144-PE-IgG were from eBioscience. Phosphate-free RPMI 1640 containing l-glutamine was from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). 32P-orthophosphate was from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). Laboratory-Tek II chambered coverglasses were from Nalge-Nunc (Rochester, NY). ML-7, Y-27632, and blebbistatin were from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA). Antibodies against the phosphorylated nonmuscle myosin II regulatory light chain (RLC) were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and antibodies against actin and nonmuscle myosin IIA (NM IIA) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibodies to ROCK-1, ROCK-2, and MLCK and Super-Femto immunoblot reagents were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated phalloidin and Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibodies were from Life Technologies. Baby rabbit complement was obtained from Pel-Freez (Rogers, AR).

Endothelial cells

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were cultured as described elsewhere.32 Cells were maintained in Medium 199 containing 10% cosmic calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), penicillin-streptomycin, and endothelial cell growth supplement. All experiments were performed using cells of passage 3 or lower.

Activation of endothelial cells by anti-β2GPI antibodies

To assess endothelial cell activation by anti-β2GPI antibodies, we measured the cell surface expression of E-selectin by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and levels of E-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), tissue factor, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) messenger RNA (mRNA) were measured by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction.33

To measure cell surface E-selectin expression, endothelial monolayers were incubated for 2 hours in serum-free M199 containing 1% bovine serum albumin and then with 100 nM β2GPI and 600 nM anti-β2GPI or control antibodies.10,33 Cells were fixed using 0.1% glutaraldehyde and then incubated with goat anti–human E-selectin, peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti–goat IgG, and the peroxidase substrate, Turbo-TMB (Pierce). The reaction was stopped by adding 1.0 M H2SO4, and amounts of endothelial cell–bound E-selectin antibodies were assessed by measuring absorbance at 450 nm. In selected studies, cells were preincubated with increasing concentrations of the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 (5 µM), the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (5 µM), and/or the nonmuscle myosin II Mg2+-ATPase inhibitor blebbistatin (50 µM), or pretreated with scrambled RNA or small interfering RNA (siRNA) to ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK. Data are expressed as the mean plus or minus standard error. Experimental points were determined in quadruplicate, and assays were repeated at least 3 times.

To assess levels of mRNA in endothelial cells exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies, RNA was isolated using TRIzol. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction analyses were performed using primer sets and conditions described in previous studies.10

Metabolic labeling of endothelial cells with 32P-orthophosphate

Metabolic labeling of endothelial cells was performed as described by Butt et al.34 Briefly, confluent cells were cultured for 60 minutes in 400 µL serum- and phosphate-free RPMI 1640. Cells were then incubated with 32P-orthophosphate at a final concentration of 500 µCi/mL, after which 80 µL of phosphate-containing RPMI was added to the medium. Cells were then incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI or control antibodies as described for endothelial activation assays.

2D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry to identify differentially phosphorylated proteins

After incubation with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies, endothelial cells were lysed using a buffer containing 2 M thiourea, 7 M urea, 65 mM CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammmonio]-1-propane-sulfinate), 58 mM dithiothreitol, and 4.5% pH 3 to 10 ampholytes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Proteins were separated by two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis using nonlinear pH 3 to 10 immobilized pH gradient strips for the first dimension and 4% to 12% acrylamide gels for the second dimension.35 Proteins were visualized by Coomassie staining and phosphoproteins by autoradiography. Spots differentially labeled with 32P-orthophosphate were identified by comparison of Coomassie-stained gel images with corresponding autoradiographs. Spots consistently differentially labeled were excised and digested with trypsin.35 For mass spectrometric analysis, excised bands were destained then dehydrated and digested with methylated porcine trypsin. Resulting peptides were extracted and the extract evaporated to <30 μL for liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis using a Thermo-Fisher LTQ ion trap mass spectrometer. Ten-microliter volumes were injected onto an 8-cm × 75-μm inner diameter Phenomenex Jupiter C18 reversed-phase capillary chromatography column and peptides eluted with an acetonitrile/0.05 M acetic acid gradient. The digest was analyzed using full-scan mass spectra to determine peptide molecular weights and product ion spectra to determine amino acid sequence. Data were analyzed using all collision-induced dissociation spectra to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information databases using the search program Mascot. Interpretation was aided by additional searches using Sequest.

Measurement of microparticles

Endothelial cells were seeded on 6-well tissue culture plates and incubated with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies. After incubation for 4 to 8 hours, medium was collected and microparticle content measured immediately using a BD LSRII flow cytometer. Briefly, medium was centrifuged at 1500g for 30 minutes. Supernatant was then recentrifuged at 13 000g for 2 minutes. A total of 50 µL supernatant was transferred to individual polystyrene tubes and incubated with 3 µL control PE-IgG (eBioscience) or anti–CD144-PE-IgG (eBioscience) to label endothelial cell–derived microparticles. A total of 200 µL of a 2.5-μm polystyrene bead solution (3.0 × 106 beads per mL) was added to each sample and used to standardize the volume analyzed. Control IgG consisted of a conjugate and isotype-matched immunoglobulin.

The upper size limit of microparticles was defined in a logarithmic forward scatter/side scatter dot plot using 1-μm calibrated latex beads (FC Size Calibration Beads; Sigma-Aldrich). The microparticle gate was drawn around the 1-μm bead population and excluded the first channel of forward scatter and side scatter. Endothelial microparticles were defined as events of size ≤1 μm expressing CD144. We established background fluorescence within the microparticle gate by incubating labeled control antibodies with microparticles. Each sample was run until 50 000 calibration beads were counted in the 2.5-µm gate. Positive events in the gated area of interest were multiplied by a concentration factor to determine the number of microparticles per mL.

In selected studies, cells were preincubated for 30 minutes prior to the addition of β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies with the MLCK inhibitor ML-7, the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632, the nonmuscle myosin II Mg2+-ATPase inhibitor blebbistatin, or a combination of these inhibitors. The role of complement in endothelial cell microparticle release in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies was also examined in the presence of purified C1q as well as unheated and heat-inactivated baby rabbit serum.

siRNA studies

To specifically define the roles of ROCK-1, ROCK-2, and MLCK in microparticle release, endothelial cells were transfected with smartpool siRNAs to these kinases (Dharmacon/Thermo Scientific) using X-tremeGENE siRNA transfection reagent (Roche USA). Briefly, 50 µL of transfection reagent was diluted using 200 µL M199 and mixed with 250 µL siRNA solution prepared by mixing 240 µL medium with 10 µL of 20 µM siRNA. Depletion of protein expression was assessed by immunoblotting 72 hours after transfection.

Immunofluorescent staining

Confluent monolayers of endothelial cells in gelatin-coated Laboratory-Tek II chambered slides were incubated with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies.36 Cells were then fixed by incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, and 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized using PBS containing 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100, and blocked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween and 1% bovine serum albumin before incubation with primary antibodies. After washing, cells were sequentially incubated with Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 568–conjugated phalloidin, and 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole prior to imaging using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Immunoblotting

Cell extracts were prepared by adding 10% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid to the dish. Extracts were collected and the protein pellet obtained by centrifugation. Pellets were washed with cold acetone, suspended in SDS sample buffer, and heated at 95°C and separated using 4% to 20% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride and incubated with primary antibodies, followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies, and bound antibodies were visualized using Super-Femto western blot reagents. To ensure equal sample loading, aliquots of samples were separated by SDS-PAGE, stained with Coomassie blue, and analyzed by total lane densitometry.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All experimental points were performed in triplicate or quadruplicate and experiments repeated at least 3 times. Experimental results were compared using the Student 2-tailed t test for paired samples. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Endothelial cell activation by anti-β2GPI antibodies leads to microparticle release

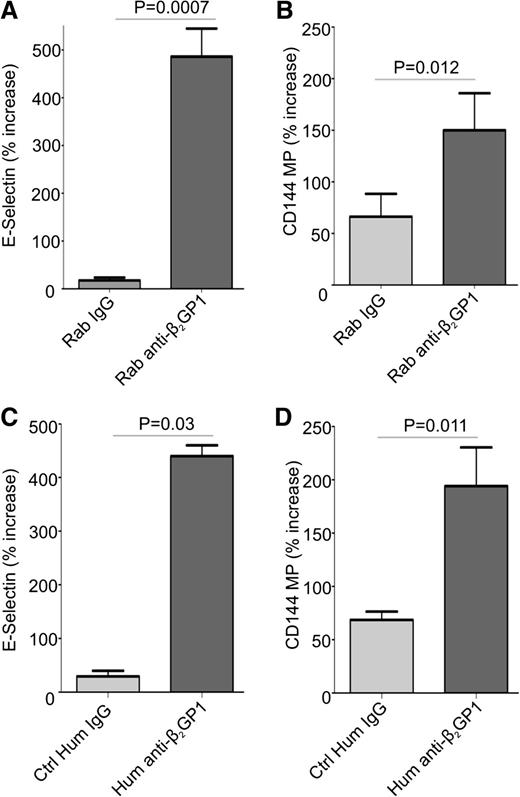

Previous studies have demonstrated that endothelial cells are activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies in the presence of β2GPI.11,17,37 We confirmed these results using endothelial cells incubated with human β2GPI and rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies (Figure 1A,C). Cells treated with rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies for 8 hours increased their expression of cell surface E-selectin to a similar extent. The expression of mRNA encoding E-selectin, ICAM-1, tissue factor, and VCAM-1 was also significantly increased in cells treated with anti-β2GPI antibodies (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site).

Anti-β2GP1 antibodies induce cell surface E-selectin expression and the release of endothelial cell microparticles. Endothelial cells were activated by incubation with 100 nM β2GP1 and 600 nM affinity-purified rabbit (A-B) or human (C-D) anti-β2GPI antibodies for 8 hours. Human IgG anti-β2GPI antibodies used in this experiment were affinity purified from a patient with a history or recurrent deep vein thrombosis who had an anti-β2GPI antibody level of 60 SGU and a lupus anticoagulant. Results obtained using anti-β2GPI IgG from this patient are representative of 2 additional patients that were also studied. Endothelial cell surface E-selectin (A,C) was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” Endothelial microparticles were measured in conditioned medium using flow cytometry after staining with anti-CD144 antibodies (B,D). For consistency, data are presented as the percent increase in E-selectin expression or microparticle release caused by control or anti-β2GPI IgG relative to that by cells incubated in medium alone. All values were determined in quadruplicate, and all assays repeated at least 3 times. Differences between control and experimental conditions were assessed using the Student 2-tailed t test. Ctrl, control; Hum, human; Rab, rabbit.

Anti-β2GP1 antibodies induce cell surface E-selectin expression and the release of endothelial cell microparticles. Endothelial cells were activated by incubation with 100 nM β2GP1 and 600 nM affinity-purified rabbit (A-B) or human (C-D) anti-β2GPI antibodies for 8 hours. Human IgG anti-β2GPI antibodies used in this experiment were affinity purified from a patient with a history or recurrent deep vein thrombosis who had an anti-β2GPI antibody level of 60 SGU and a lupus anticoagulant. Results obtained using anti-β2GPI IgG from this patient are representative of 2 additional patients that were also studied. Endothelial cell surface E-selectin (A,C) was measured as described in “Materials and methods.” Endothelial microparticles were measured in conditioned medium using flow cytometry after staining with anti-CD144 antibodies (B,D). For consistency, data are presented as the percent increase in E-selectin expression or microparticle release caused by control or anti-β2GPI IgG relative to that by cells incubated in medium alone. All values were determined in quadruplicate, and all assays repeated at least 3 times. Differences between control and experimental conditions were assessed using the Student 2-tailed t test. Ctrl, control; Hum, human; Rab, rabbit.

To determine whether anti-β2GPI antibodies induced release of microparticles from endothelial cells, conditioned medium from cells incubated with β2GPI and rabbit or human anti-β2GPI antibodies, or control IgG, was compared. Microparticle release occurred in a time-dependent manner, with differences in release from cells incubated with control IgG or anti-β2GPI antibodies apparent after 8 hours (supplemental Figure 2); this time point was used for subsequent studies. Though microparticles were detected in conditioned medium from cells incubated under all conditions, two- to threefold more were released in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies than control IgG (Figure 1B,D). Due to similar responses to affinity-purified human or rabbit anti-β2GPI antibodies, and to ensure a consistent source of anti-β2GPI antibodies for all experiments, rabbit anti-β2GPI antibodies were used for subsequent studies.

The addition of C1q or baby rabbit serum to cells as a source of complement during anti-β2GPI–induced endothelial cell activation enhanced neither endothelial E-selectin expression nor microparticle release (supplemental Figure 3).

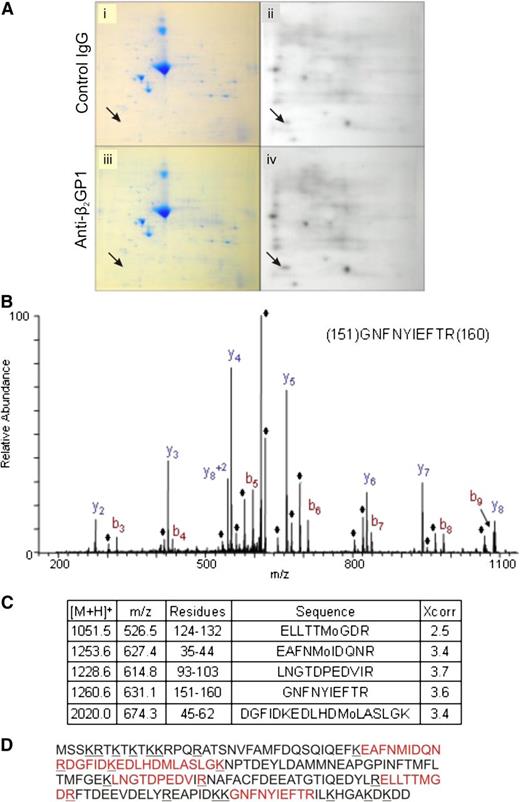

Identification of a novel phosphoprotein in endothelial cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies

We used a 2D gel system to identify protein phosphorylation during activation of endothelial cells by anti-β2GPI antibodies. Compared with cells exposed to control antibodies (Figure 2A, panels i-ii), exposure of cells to anti-β2GPI antibodies resulted in differential radiolabeling of several proteins with 32P-orthophosphate (Figure 2A, panels iii-iv). A protein that demonstrated a consistent increase in phosphorylation across 5 experiments following exposure of cells to β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies that was selected for study is depicted by arrows in Figure 2A. Other proteins were phosphorylated following exposure to β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, but differences were less robust.

Assessment of protein phosphorylation in cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies. Endothelial cells were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate in serum and phosphate-free media prior to addition of β2GPI and either control IgG or affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies. Total cell lysates were subjected to 2D SDS-PAGE. (A) Coomassie staining (i,iii) and autoradiography (ii,iv) of total cell lysates from cells incubated with β2GPI and control IgG (i-ii), or β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies (iii-iv). Arrows point to the protein spot demonstrating consistently increased phosphorylation following incubation of cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies. (B) Mass spectrometric profile of the differentially phosphorylated protein following tryptic digestion. The ions denoted with the ♦ represent H2O loss peaks. (C) The 5 myosin RLC peptides identified in this analysis, including the Sequest Xcorr score for each peptide. (D) Sequence of myosin RLC with the peptides positively identified in the LC-MS/MS analysis shown in red.

Assessment of protein phosphorylation in cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies. Endothelial cells were metabolically labeled with 32P-orthophosphate in serum and phosphate-free media prior to addition of β2GPI and either control IgG or affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies. Total cell lysates were subjected to 2D SDS-PAGE. (A) Coomassie staining (i,iii) and autoradiography (ii,iv) of total cell lysates from cells incubated with β2GPI and control IgG (i-ii), or β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies (iii-iv). Arrows point to the protein spot demonstrating consistently increased phosphorylation following incubation of cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies. (B) Mass spectrometric profile of the differentially phosphorylated protein following tryptic digestion. The ions denoted with the ♦ represent H2O loss peaks. (C) The 5 myosin RLC peptides identified in this analysis, including the Sequest Xcorr score for each peptide. (D) Sequence of myosin RLC with the peptides positively identified in the LC-MS/MS analysis shown in red.

Using in-gel digestion and analysis of tryptic peptides by mass spectrometry (Figure 2B), this phosphoprotein was identified as myosin II RLC, a ∼20 kDa cytoskeletal protein identified from sequences of 5 different peptides covering 38% of the protein sequence (Figure 2C). Figure 2D depicts the full sequence of RLC with positions of identified peptides denoted. All peptides had masses within 2.5 Da of that predicted from the native sequence.

Direct assessment of RLC phosphorylation

RLC is an essential component of nonmuscle myosin II (NM II) motor proteins ubiquitously expressed in nonmuscle cells. The NM II system includes myosin IIA motor protein, which exists as a complex consisting of 2 myosin II heavy chains (MHCs), 2 essential light chains, and 2 RLCs. The activity of NM II motor proteins is regulated by RLC phosphorylation, which increases Mg2+-ATPase activity in the MHC head domain and induces conformational changes in the heavy chains leading to association of the NM II motor protein with actin.

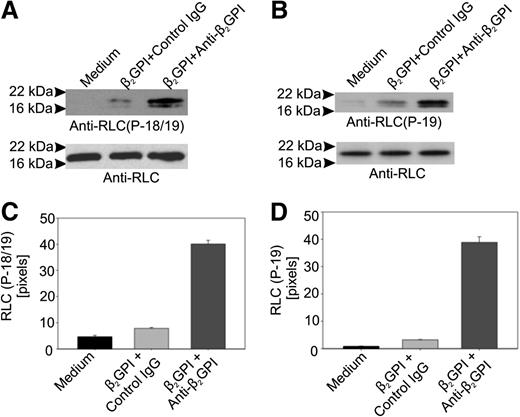

We assessed whether RLC phosphorylation occurred in anti-β2GPI antibody-treated cells using antibodies specific for an epitope formed by phosphorylation of RLC threonine 18/serine 19 (T18/S19) or S19 alone. In cells incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, the reactivity of both phosphorylation-dependent antibodies with RLC was markedly increased compared with cells incubated in medium alone or with β2GPI and control IgG (Figure 3).

Anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate phosphorylation of myosin RLC. (A) Phosphorylation of RLC residues T18 and S19 in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies. Total lysates prepared from endothelial cells incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies for 60 minutes were subjected to immunoblotting using an anti–phospho-RLC (T18/S19) antibody. After blotting with the phosphorylation-specific antibody, blots were stripped and reblotted with an antibody to RLC. (B) The same lysates depicted in panel A were immunoblotted using an antibody specific for phosphorylated S19 in RLC. (C) Densitometric analysis of panel A using NIH ImageJ. (D) Densitometric analysis of panel B using NIH ImageJ.

Anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate phosphorylation of myosin RLC. (A) Phosphorylation of RLC residues T18 and S19 in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies. Total lysates prepared from endothelial cells incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies for 60 minutes were subjected to immunoblotting using an anti–phospho-RLC (T18/S19) antibody. After blotting with the phosphorylation-specific antibody, blots were stripped and reblotted with an antibody to RLC. (B) The same lysates depicted in panel A were immunoblotted using an antibody specific for phosphorylated S19 in RLC. (C) Densitometric analysis of panel A using NIH ImageJ. (D) Densitometric analysis of panel B using NIH ImageJ.

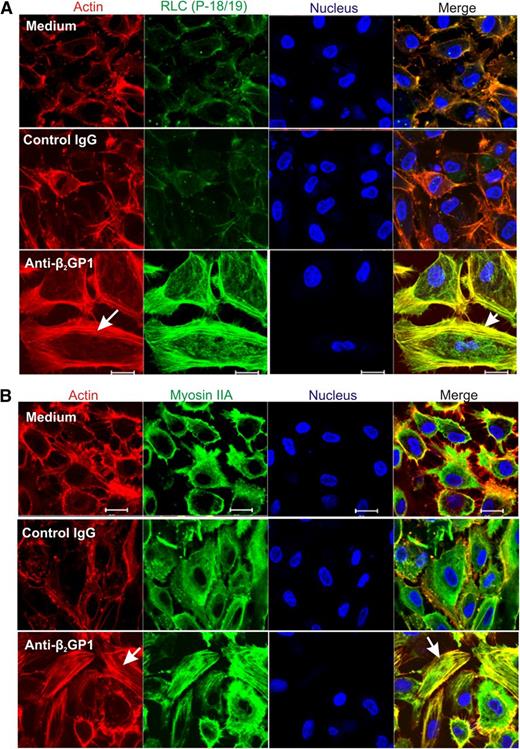

Effects of RLC phosphorylation on the endothelial cell cytoskeleton

To assess the effects of RLC phosphorylation in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies on the endothelial cell cytoskeleton, cells were permeabilized to allow intracellular localization of phosphorylated RLC, actin, and myosin IIA. As shown in Figure 4A, phosphorylated RLC (T18/S19) was detected on intracellular filaments in cells exposed to anti-β2GPI antibodies, but not in cells incubated in medium alone, or with β2GPI and control IgG. Colocalization of RLC with filamentous actin (F-actin) was evident on analysis of merged images of cells costained with phalloidin–Alexa Flour 568. Incubation of endothelial cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies also led to actin-myosin association, as demonstrated by colocalization of actin and myosin IIA filaments (Figure 4B, lower right panel).

Immunolocalization of phosphorylated RLC and myosin IIA in anti-β2GPI antibody-exposed endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were incubated with medium alone, or with β2GPI and either control or anti-β2GPI antibodies, and then fixed and stained with RLC (P-18/19) or myosin IIA antibodies. Cells were also stained with phalloidin to study formation of the actin network, and with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole to localize nuclei. (A) Assembly of the actin network (arrow, lower left panel) occurs exclusively in cells treated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, with colocalization of phosphorylated RLC and actin (arrow, lower right panel). (B) Incubation of cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies causes actin assembly (arrow, lower left panel), as well as actin-myosin association, as demonstrated by colocalization of these 2 proteins (arrow, lower right panel). Confocal images were collected using a ×63 oil objective with 1.4 numerical aperture on a Zeiss LSM 501 microscope. Bar represents 20 μm.

Immunolocalization of phosphorylated RLC and myosin IIA in anti-β2GPI antibody-exposed endothelial cells. Endothelial cells were incubated with medium alone, or with β2GPI and either control or anti-β2GPI antibodies, and then fixed and stained with RLC (P-18/19) or myosin IIA antibodies. Cells were also stained with phalloidin to study formation of the actin network, and with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole to localize nuclei. (A) Assembly of the actin network (arrow, lower left panel) occurs exclusively in cells treated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies, with colocalization of phosphorylated RLC and actin (arrow, lower right panel). (B) Incubation of cells with anti-β2GPI antibodies causes actin assembly (arrow, lower left panel), as well as actin-myosin association, as demonstrated by colocalization of these 2 proteins (arrow, lower right panel). Confocal images were collected using a ×63 oil objective with 1.4 numerical aperture on a Zeiss LSM 501 microscope. Bar represents 20 μm.

Role of RLC phosphorylation in E-selectin expression and microparticle release in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies

To assess the role of RLC phosphorylation and assembly of the actin network in endothelial cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies, we determined the effects of inhibiting RLC phosphorylation on cell surface E-selectin expression and the release of microparticles.

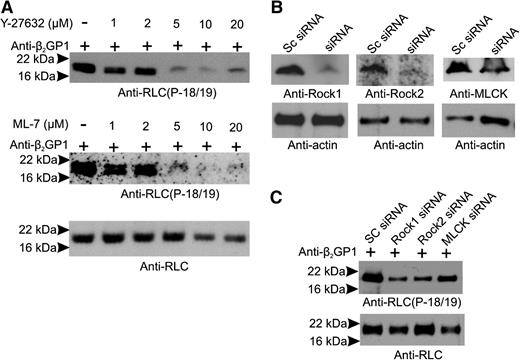

RLC phosphorylation may occur via Rho-associated protein kinases (ROCK-1 and ROCK-2) or RLC/myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), which may be phosphorylated by ERK 1/2.38 Anti-β2GPI antibodies activate monocytes39 and endothelial cells,40 in part via ERK 1/2, a finding confirmed in this study (supplemental Figure 4). To address the roles of MLCK, ROCK, and the Mg2+-ATPase activity of the NM II motor domain in endothelial activation, cells were incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GP1 antibodies in the absence and presence of the MLCK inhibitor ML-7, the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632, blebbistatin (which inhibits the Mg2+-ATPase activity of the NM II motor domain), or a combination of inhibitors. Cells were also separately treated with siRNA to ROCK-1, ROCK-2, and MLCK. As shown in Figure 5A, ML-7 and Y-27632 blocked phosphorylation of RLC in response to anti-β2GP1 antibodies in a dose-dependent manner, with maximal inhibition at a concentration of 5 µM. Likewise, siRNA to ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK significantly reduced their levels (Figure 5B), markedly inhibiting RLC phosphorylation (Figure 5C).

RLC phosphorylation in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies is prevented by MLCK or ROCK inhibition. Endothelial cells were incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 or the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632. (A) Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phosphoRLC (T18/S19) (upper and middle panels) or anti-RLC (total protein). (B) Endothelial cells were treated with scrambled (Sc) RNA (control) or siRNA specific for ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK; blotting with anti-actin antibodies was used to demonstrate equal loading. (C) Effect of siRNA knockdown of ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK on levels of phosphorylated RLC. Significant inhibition was caused by knockdown of each of the kinases.

RLC phosphorylation in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies is prevented by MLCK or ROCK inhibition. Endothelial cells were incubated with β2GPI and anti-β2GPI antibodies in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the MLCK inhibitor ML-7 or the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632. (A) Lysates were immunoblotted with anti-phosphoRLC (T18/S19) (upper and middle panels) or anti-RLC (total protein). (B) Endothelial cells were treated with scrambled (Sc) RNA (control) or siRNA specific for ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK; blotting with anti-actin antibodies was used to demonstrate equal loading. (C) Effect of siRNA knockdown of ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK on levels of phosphorylated RLC. Significant inhibition was caused by knockdown of each of the kinases.

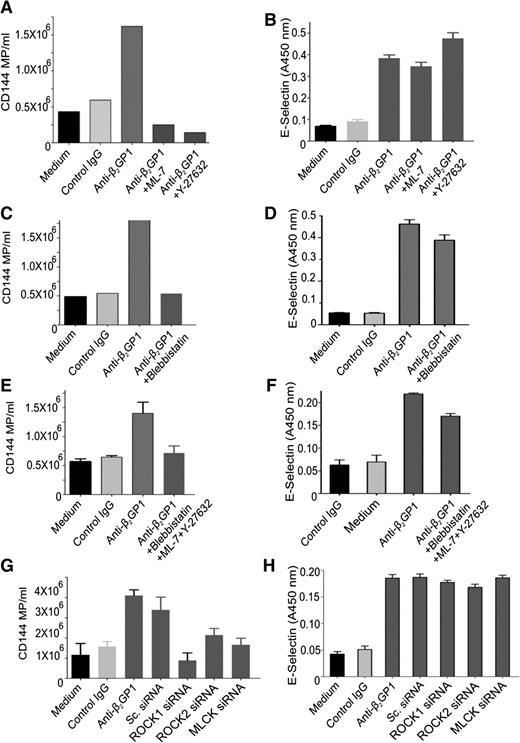

Inhibition of RLC phosphorylation by either ML-7 or Y-27632 (Figure 6A) or blebbistatin (Figure 6C) inhibited the enhanced release of microparticles from endothelial cells stimulated with anti-β2GPI antibodies, reducing microparticle release to levels below those observed constitutively. There was no additive effect of using the inhibitors simultaneously (Figure 6E). Similar effects were seen with siRNA-mediated knockdown of ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK (Figure 6G). However, inhibition of RLC phosphorylation by chemical inhibitors or kinase knockdown did not affect the increased expression of endothelial cell surface E-selectin (Figure 6B,D,F,H). Levels of E-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, or tissue factor mRNA were also unaffected.

Effect of inhibiting RLC phosphorylation stimulated by anti-β2GPI antibodies on endothelial microparticle release and cell surface E-selectin expression. Endothelial cells were incubated in medium alone or with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies for 8 hours and the release of microparticles and cell surface expression of E-selectin quantified as described in “Materials and methods.” Inhibitors used include Y-27632 (5 µM), ML-7 (5 µM), or blebbistatin (50 µM). Inhibitors were used alone or in combination, as depicted in abscissa of each graph. (A,C,E,G) The effects of inhibitors or specific siRNA on endothelial cell microparticle release induced by anti-β2GPI antibodies. (B,D,F,H) The effects of inhibitors or specific siRNA on endothelial E-selectin expression induced by anti-β2GPI antibodies.

Effect of inhibiting RLC phosphorylation stimulated by anti-β2GPI antibodies on endothelial microparticle release and cell surface E-selectin expression. Endothelial cells were incubated in medium alone or with β2GPI and control or anti-β2GPI antibodies for 8 hours and the release of microparticles and cell surface expression of E-selectin quantified as described in “Materials and methods.” Inhibitors used include Y-27632 (5 µM), ML-7 (5 µM), or blebbistatin (50 µM). Inhibitors were used alone or in combination, as depicted in abscissa of each graph. (A,C,E,G) The effects of inhibitors or specific siRNA on endothelial cell microparticle release induced by anti-β2GPI antibodies. (B,D,F,H) The effects of inhibitors or specific siRNA on endothelial E-selectin expression induced by anti-β2GPI antibodies.

Discussion

Levels of circulating endothelial cell microparticles are increased in patients with APLA/anti-β2GPI antibodies,24,28 though the mechanisms by which these antibodies induce microparticle release are unknown. Here, we demonstrate that anti-β2GPI antibodies induce release of microparticles from endothelial cells and that this process depends upon phosphorylation of the myosin RLC and assembly of actin-myosin networks. Inhibition of RLC phosphorylation blocks actin-myosin assembly and microparticle release, though other effects of anti-β2GPI antibody-induced endothelial activation, such as increased expression of cell surface E-selectin, are unaffected. These findings are among the first to define mechanisms by which anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate endothelial cell microparticle release and to dissociate pathways that result in distinct consequences of endothelial cell activation.

Although we expected to identify several proteins whose phosphorylation levels would increase after exposure of cells to anti-β2GPI antibodies, RLC was the primary protein that was consistently phosphorylated. This reflects the fact that 2D electrophoresis resolves only a small fraction of intracellular proteins leading to overrepresentation of cytoskeletal proteins.35

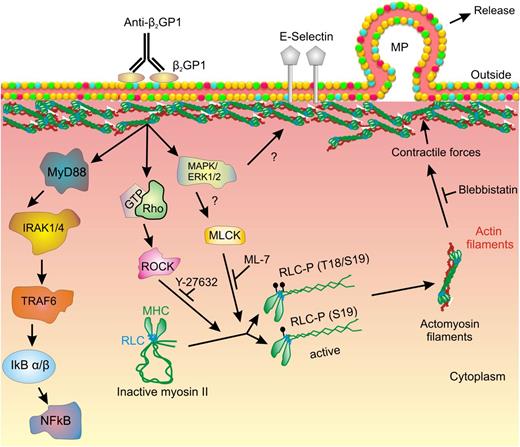

Myosin RLC regulates the activity of the NM II motor protein through binding the MHC. The MHC consists of an N-terminal globular motor domain (head) containing Mg2+-ATPase activity, which is stimulated following RLC phosphorylation leading to a conformational change in the myosin heads.41 The head region is followed by a short neck region that contains binding sites for the RLC as well as the essential light chain, which stabilizes the heavy chain. An α-helical coiled-coil C-terminal domain mediates heavy chain dimerization and terminates in a short nonhelical tail region unique among the 3 NM II heavy chain proteins (NM II A, B and C).41 In the inactive state, the MHC C-terminal tail domain folds back and attaches to the RLC. However, phosphorylation of RLC by MLCK, ROCK-1, or ROCK-242 leads to unfolding of the MHC, followed by its assembly into filaments with high affinity for filamentous actin (Figure 7). Myosin II filaments formed by association with F-actin generate intracellular forces leading to development of isometric tension and contraction.41,42

Mechanism of myosin II–mediated release of microparticles from endothelial cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies. In this diagram, crosslinking of β2GPI bound to a cell surface receptor (ie, annexin A2) leads to activation of intracellular signaling, including the TLR4–NF-κB pathway. ERK 1/2 and ROCK are also activated, though the pathways leading to activation of these kinases have not been clearly defined. We propose that ERK mediates activation of MLCK and that MLCK and ROCK mediate phosphorylation of RLC on T18/S19; activation by both MLCK and ROCK may be needed to achieve sufficient RLC phosphorylation to trigger subsequent events. Phosphorylated RLC causes the myosin heavy chain to unfold and bind actin, leading to submembranous actin-myosin assembly. Submembranous contractile forces promote budding of microparticles from the endothelial cell surface membrane. Y-27632, ML-7, and blebbistatin inhibit various steps in this pathway, impairing microparticle release. However, the expression of cell surface E-selectin is not impaired by these inhibitors.

Mechanism of myosin II–mediated release of microparticles from endothelial cells activated by anti-β2GPI antibodies. In this diagram, crosslinking of β2GPI bound to a cell surface receptor (ie, annexin A2) leads to activation of intracellular signaling, including the TLR4–NF-κB pathway. ERK 1/2 and ROCK are also activated, though the pathways leading to activation of these kinases have not been clearly defined. We propose that ERK mediates activation of MLCK and that MLCK and ROCK mediate phosphorylation of RLC on T18/S19; activation by both MLCK and ROCK may be needed to achieve sufficient RLC phosphorylation to trigger subsequent events. Phosphorylated RLC causes the myosin heavy chain to unfold and bind actin, leading to submembranous actin-myosin assembly. Submembranous contractile forces promote budding of microparticles from the endothelial cell surface membrane. Y-27632, ML-7, and blebbistatin inhibit various steps in this pathway, impairing microparticle release. However, the expression of cell surface E-selectin is not impaired by these inhibitors.

Microparticle formation is a complex process that involves an interplay among signal transduction; lipid membrane remodeling by flippase, floppase, and scramblase; and the coordinated activation, assembly, and disruption of the underlying cytoskeleton.31 One report implicated the Rho kinase ROCK-2 in the release of endothelial cell microparticles in response to thrombin.43 Activation of ROCK was mediated by caspase-2, and both ROCK activation and microparticle release was inhibited by ZVAD-FMK, a caspase-2 inhibitor. In another report, endothelial microparticle release caused by angiotensin II was mediated via angiotensin II receptor type I and ROCK and was associated with superoxide production.44 In these studies, our results are limited to detection of microparticles greater than approximately 400 nM in size that are resolved by flow cytometry. The role of the cytoskeleton in release of smaller vesicles, including exosomes, is uncertain.

A remarkable aspect of our studies is the dramatic assembly of the actin-myosin network in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies.31 Latham et al recently reported a similar response to endothelial cell activation by cytokines and other agonists that stimulate microparticle release.45 These investigators defined 2 groups of agonists, one that induced rapid microparticle release (A23187, TRAP-6) and a second that did so over a period of 6 to 12 hours (tumor necrosis factor α, lipopolysaccharide, interferon γ), similar to that observed by anti-β2GPI antibodies. Microparticle release was postulated to occur following assembly of basal stress fibers that drove perinuclear particulate actin-rich structures upward, disrupting the apical γ-actin network and leading to membrane protuberances ultimately released as microparticles. The studies reported in here, though not analyzing β- and γ-actin separately, confirm a critical role for the cytoskeleton in microparticle release in response to a clinically important pathophysiological stimulus and demonstrate that this response may be disassociated from other membrane-dependent events.

Prior studies have demonstrated elevated levels of circulating endothelial cell microparticles in patients with APLAs 24,28 that were detected at times distinct from acute thrombotic events. Though the relationship between a two- to threefold stimulation of endothelial cell microparticle release by anti-β2GPI antibodies in vitro to the development of thrombosis in patients with APS requires further study, elevated levels of microparticles provides evidence of subclinical vascular activation46,47 that may contribute to disease pathogenesis. Microparticle release might be further enhanced in vivo by additional effectors such as complement,48 though complement did not enhance microparticle release in vitro.

Two additional studies have assessed the effects of APLAs on endothelial cell microparticle release in vitro.24,49 One demonstrated increased vesiculation of the endothelial membrane, reflecting nascent microparticles, in response to APLAs.24 The second demonstrated increased release of microparticles from endothelial cells incubated with IgG fractions from 28 women with APS, compared with 8 controls.49 However, neither of these studies assessed the effects of isolated anti-β2GPI antibodies, nor were mechanisms underlying microparticle release explored.

Our results provide new information concerning potential pathogenic mechanisms of APLA/anti-β2GPI antibodies. First, we determined that microparticle release in response to anti-β2GPI antibodies was reduced to baseline levels by the ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 and the MLCK inhibitor ML-7. Microparticle release was also inhibited by blebbistatin, an inhibitor of the Mg2+-ATPase activity of the NM II motor domain. A combination of these 3 inhibitors did not inhibit microparticle release further, suggesting that 2 pathways converge to stimulate release. Knockdown of ROCK-1, ROCK-2, or MLCK with siRNA also led to inhibition of RLC phosphorylation and release of microparticles, supporting the specificity of the chemical inhibitors.

Although we did not define the upstream activator of MLC kinase, previous work suggests that this occurs in response to ERK 1/2.50 Prior reports demonstrate that induction of monocyte tissue factor mRNA and protein by anti-β2GPI antibodies was dependent upon p38 and ERK 1/2 39 and that anti-β2GPI antibodies activate the Ras-ERK pathway in endothelial cells,40 a finding confirmed in this study (supplemental Figure 4). However, inhibition of microparticle release by Y-27632, ML-7, blebbistatin, or ROCK or MLCK siRNA did not affect the cell surface expression of E-selectin, a process dependent upon the TLR4–NF-κB pathway.19 Thus, our studies demonstrate that distinct pathways regulate cell surface adhesion molecule expression and microparticle release (Figure 7).

Why inhibition of MLCK and ROCK individually blocks microparticle release despite the fact that they phosphorylate the same target is uncertain, but suggests that a threshold for RLC phosphorylation is needed to stimulate NM II interaction with actin and that both kinases are required to achieve that threshold. This finding is reminiscent of a report in which inhibition of ERK 1/2, p38, or NF-κB inhibited monocyte tissue factor expression in response to APLA/anti-β2GPI antibodies despite the fact that these antibodies activated all 3 pathways.39

In summary, we have demonstrated that anti-β2GPI antibodies stimulate assembly of the actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cells by inducing phosphorylation of the myosin RLC. Inhibition of RLC phosphorylation blocks microparticle release. Reducing levels of circulating microparticles in patients with APLA/anti-β2GPI antibodies through manipulation of this pathway might provide a potential approach for management of the prothrombotic state associated with APS.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL089796 and P50HL081011) (K.R.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.R.M., G.L., and V.B. conceived the project and designed the experiments; K.R.M. and V.B. wrote the manuscript; and V.B., G.L., L.H., and M.W. performed the experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Keith R. McCrae, Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, R4-018, Cleveland, OH 44195; e-mail mccraek@ccf.org.