Key Points

The tumor microenvironment drives myeloma cell clonogenic growth and self-renewal through GDF15.

Abstract

Disease relapse remains a major factor limiting the survival of cancer patients. In the plasma cell malignancy multiple myeloma (MM), nearly all patients ultimately succumb to disease relapse and progression despite new therapies that have improved remission rates. Tumor regrowth indicates that clonogenic growth potential is continually maintained, but the determinants of self-renewal in MM are not well understood. Normal stem cells are regulated by extrinsic niche factors, and the tumor microenvironment (TME) may similarly influence tumor cell clonogenic growth and self-renewal. Growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15) is aberrantly secreted by bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) in MM. We found that GDF15 is produced by BMSCs after direct contact with plasma cells and enhances the tumor-initiating potential and self-renewal of MM cells in a protein kinase B- and SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box–dependent manner. Moreover, GDF15 induces the expansion of MM tumor-initiating cells (TICs), and changes in the serum levels of GDF15 were associated with changes in the frequency of clonogenic MM cells and the progression-free survival of MM patients. These findings demonstrate that GDF15 plays a critical role in mediating the interaction among mature tumor cells, the TME, and TICs, and strategies targeting GDF15 may affect long-term clinical outcomes in MM.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is characterized by the clonal expansion of malignant plasma cells. Advances in MM treatment have significantly improved remission rates, but the vast majority of patients will eventually relapse and succumb to their disease.1 The continuous risk of relapse suggests that therapy-resistant tumor cells are self-renewing and indefinitely maintain the potential for clonogenic growth. The factors influencing MM self-renewal are poorly understood, but normal stem cells are extrinsically regulated by accessory cells and extracellular matrix components within niches.2,3 Therefore specific factors within the tumor microenvironment (TME) may similarly influence MM cell clonogenic growth and self-renewal.

Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) are a major component of the TME in MM and aberrantly secrete several cytokines including growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15, also known as MIC-1, PTGF-β, PDF, PLAB, PL74, and NAG-1), a member of the transforming growth factor-β family.4-6 Elevated circulating levels of GDF15 may correlate with poor clinical outcomes in endometrial, prostate, pancreatic, and colorectal cancers.7-10 Similarly, increased GDF15 levels have correlated with disease stage and been associated with worse event-free survival and overall survival in MM patients.5 GDF15 may enhance the survival of MM cells in vitro.4,5 However, these effects are relatively modest, suggesting that GDF15 influences other properties such as self-renewal and clonogenic growth, which better explain the relationship between circulating cytokine levels and clinical outcomes.

We examined the effects of GDF15 on clonogenic MM growth and found that it increased both tumor cell colony formation in vitro and the engraftment of immunodeficient mice in a protein kinase B- and SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box (SOX2)–dependent manner. To evaluate self-renewal, we carried out serial transplantation studies and found that secondary MM engraftment was increased by the treatment of tumor cells with GDF15 and impaired by the loss of GDF15 within the bone marrow microenvironment. Moreover, the impact of GDF15 on the clonogenic growth and self-renewal of human MM was limited to phenotypically defined tumor-initiating cells (TICs) rather than bulk tumor cells. Finally, we studied the relationship between GDF15 and MM TICs in the clinical setting and found that changes in the serum levels of GDF15 were associated with changes in in vitro clonogenic MM growth and progression-free survival. Therefore GDF15 plays a novel role within the TME by enhancing the tumor-initiating potential and self-renewal of MM TICs, and the development of strategies targeting GDF15 may represent a novel approach for the treatment of MM.

Methods

Cell lines and clinical specimens

Human MM cell lines NCI-H929, RPMI 8226, U266, and MM1.S were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and KMS11 cells from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (National Institutes of Health Sciences, Japan). Cells were cultured in complete media (CM) as previously described.11 Cells were incubated with human recombinant GDF15 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), the Akt-1/2 inhibitor (124018; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), or a mouse anti-human GDF15 monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for the indicated doses and time periods. For long-term treatment with GDF15, cells were collected by centrifugation (300g) and resuspended in CM containing GDF15 twice per week.

Clinical bone marrow and peripheral blood samples were obtained from MM patients or healthy donors who gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes Institutional Review Board. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated by density centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), and plasma cells were isolated using anti-CD138 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Peripheral blood GDF15 levels were measured using the DuoSet enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human GDF15 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Human primary BMSCs were obtained from 4 MM patients and 4 healthy volunteers by culturing bone marrow mononuclear cells (106 cells/mL) in 25 cm2 tissue culture flasks coated with 0.1% gelatin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and CM containing 10% horse serum. After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, nonadherent cells were removed and the adherent fraction was cultured in fresh media. MM cell lines and plasma cells derived from clinical specimens (5 × 104 cells) were either combined with BMSCs (5 × 104 cells at passage 2-4) or cultured using cell culture inserts (0.8 μm pores; Greiner Bio One, Monroe, NC) for 4 days and then evaluated for GDF15 production and tumor cell colony formation.

Tumor cell colony formation

After treatment, tumor cell colony formation in methylcellulose was used to quantify in vitro clonogenic growth according to our previously published methods.11,12 MM cell lines (1000 cells/mL) were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after treatment then plated in triplicate into 35-mm2 tissue culture dishes containing 1.2% methylcellulose, 30% fetal bovine serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol, and 2 mM L-glutamine. For clinical specimens, mononuclear cells were isolated from primary clinical bone marrow aspirates, depleted of CD34+ and CD138+ cells using magnetic microbeads, treated with GDF15, and then plated (5 × 105/mL) in methylcellulose cultures containing 10% lymphocyte conditioned media as a source of growth factors. After 10 to 21 days of culture at 37°C and 5% CO2, tumor colonies consisting of >40 cells were quantified using an inverted microscope. For serial plating studies, tumor cell colonies were harvested, washed twice in CM, and resuspended (1000 cells/mL) in methylcellulose.

Mouse transplantation

All animal studies were approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutes Animal Care Committee. NCI-H929 and RPMI 8226 cells were injected via tail vein into NSG (NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ) mice. For ex vivo GDF15 treatment, cells were washed twice in PBS before injection. After the development of hind limb paralysis, or after 6 months, engraftment was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for serum human immunoglobulin (Ig) κ light chain (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) and human CD138+ cells within the bone marrow by flow cytometry. Secondary transplants were carried out by determining the concentration of human CD138+ cells within the bone marrow of primary recipients by flow cytometry, then injecting whole bone marrow cells containing 5 × 103 human CD138+ cells into secondary recipients. For Vk*Myc mouse tumor cells (1 × 104), Gdf15 null or wild-type C57/Bl6 recipients were conditioned with 6 Gy whole-body irradiation before intravenous injection. Tumor engraftment was evaluated by the identification of monoclonal Ig production by serum protein electrophoresis (The Binding Site, San Diego, CA) and increased (>10%) bone marrow mouse CD138+ cells by flow cytometry. Secondary transplants were carried out by injecting whole bone marrow cells containing 1 × 104 mouse CD138+ cells into irradiated wild-type C57/Bl6 animals. TIC frequency was determined using ELDA software.13

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RNA samples were extracted using the RNeasy mini plus kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was carried out using the SYBR green system (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). All quantitative calculations were performed using the ΔΔct method, and primer sequences included: GDF15, 5′-CTCCAGATTCCGAGAGTTGC-3′, 5′-AGAGATACGCAGGTGCAGGT-3′; SOX2, 5′-CCGGTACGCTCAAAAAGAAA-3′, 5′-AGTGTGGATGGGATTGGTGT-3′; and ACTB, 5′-ATCCACGAAACTACCTTCAACTCCAT-3′, 5′- CATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATC-3′.

Transient transfections

NCI-H929 cells were transfected with 300 nM SOX2 or scrambled control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) using the Nucleofector system (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), and 24 hours after transfection, the culture media were replaced with fresh media containing 100 ng/mL GDF15. SOX2 knockdown was evaluated by qRT-PCR 3 days after transfection.

Immunoblot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out on whole-cell lysates prepared from NCI-H929 cells, separated by 4% to 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), then incubated with antibodies against phospho-AKT, AKT, and BMI-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) as well as SOX2 and β-ACTIN (EMD Millipore). Antigen detection was carried out using a goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase and the Supersignal West Chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Flow cytometry and cell isolation

Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated mouse anti-human CD138, R-phycoerythrin rat anti-mouse CD138, or relevant isotypic control antibodies (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were stained for aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity using the Aldefluor reagent (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were subsequently washed and resuspended in PBS containing 5 μM propidium iodide (PI; Sigma) and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) or isolated using a FACSAria II cell sorter. Cells were initially gated to exclude PI+ cells and then analyzed for CD138 or ALDH expression. After cell sorting, flow cytometry demonstrated <5% contamination by relevant antigen-expressing cells.

Data analysis

A Student t test was used to detect differences, and significance was defined as P < .05. Association between trends in serum GDF15 levels and MM–colony-forming unit (CFU) counts in 15 MM patients was determined using the Fisher exact test. Survival rate and progression-free survival were expressed as the percentage of surviving patients calculated using the Kaplan-Meir method. The log-rank test was used to test the difference between the study groups. These analyses were carried out in STATA version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

GDF15 enhances clonogenic MM growth and self-renewal

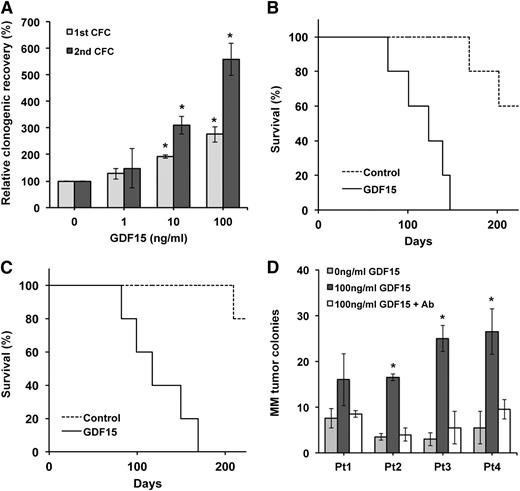

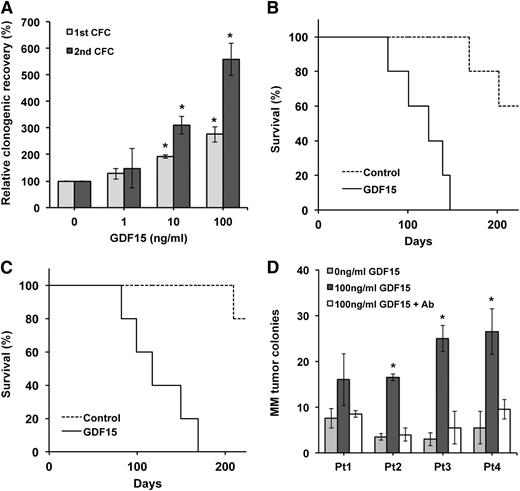

To determine the effects of GDF 15 on clonogenic MM growth, we quantified the effects of GDF15 on the colony-forming potential of MM cell lines. Compared with vehicle-treated cells, GDF15 significantly increased the colony formation of NCI-H929 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 1A; P < .01). Moreover, this increase was maintained through secondary colony formation despite no further treatment with GDF15 (Figure 1A; P < .01). We similarly found that GDF increased the colony formation of RPMI 8226, U266, KMS12, and MM1.S MM cells as well (supplemental Figure 1A-B, available on the Blood Web site).

GDF15 enhances the clonogenic growth of MM. (A) Primary and secondary colony formation (CFC) of NCI-H929 cells cultured with GDF15 for 7 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15. (B) Survival of NSG mice after injection of NCI-H929 cells treated ex vivo with or without GDF15 (100 ng/mL) for 14 days (n = 5 for each condition). (C) Survival of mice after secondary transplantation of GDF15 cells. (D) MM colony formation by primary clinical bone marrow specimens after treatment with GDF15 ± anti-GDF15 antibody (Ab) for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15.

GDF15 enhances the clonogenic growth of MM. (A) Primary and secondary colony formation (CFC) of NCI-H929 cells cultured with GDF15 for 7 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15. (B) Survival of NSG mice after injection of NCI-H929 cells treated ex vivo with or without GDF15 (100 ng/mL) for 14 days (n = 5 for each condition). (C) Survival of mice after secondary transplantation of GDF15 cells. (D) MM colony formation by primary clinical bone marrow specimens after treatment with GDF15 ± anti-GDF15 antibody (Ab) for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15.

To determine the impact of GDF15 on tumor initiation in vivo, we injected NCI-H929 cells into NSG mice after 14 days of ex vivo treatment. GDF15 treatment significantly increased tumor initiation because all mice receiving GDF15-treated cells were symptomatic and had detectable serum human IgG κ light chain and bone marrow plasma cells by 6 months compared with 40% of animals injected with the same number of vehicle-treated cells (Figure 1B; P < .0004). We also carried out limiting dilution studies and found that GDF15 treatment significantly increased the frequency of TICs more than tenfold over control-treated cells (Table 1; P < .0041). To assess the effects of GDF15 on MM self-renewal, we carried out serial transplants and found that all secondary recipients receiving cells originally treated ex vivo with GDF15 engrafted with MM compared with 20% of mice transplanted with bone marrow cells from mice initially injected with control cells (Figure 1C; P < .0002).

We also examined the effects of GDF15 primary MM clinical specimens and found similar effects on tumor colony formation for all of the samples we studied (Figure 1D). In addition, this increase in clonogenic growth was specific for GDF15 because it could be blocked using an anti-GDF15 neutralizing antibody. Collectively, these results demonstrate that GDF15 acts in a specific manner to enhance clonogenic MM growth and self-renewal both in vitro and in vivo.

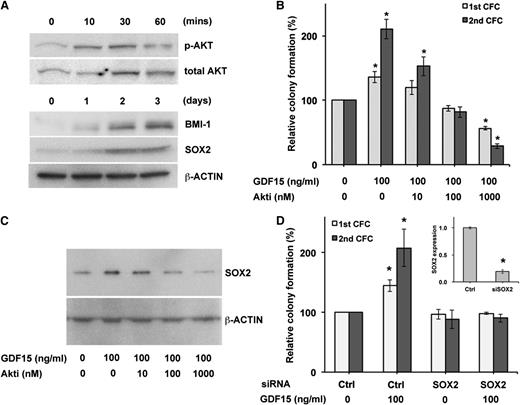

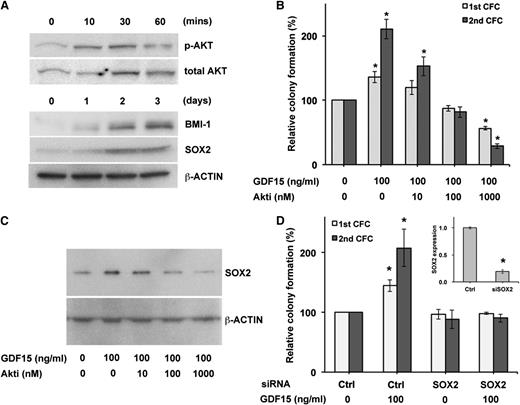

AKT-SOX2 signaling is required for the effects of GDF15 on MM

To examine the cellular processes responsible for the effects of GDF15 on clonogenic growth, we examined the AKT signaling pathway because it is activated by GDF15 in both normal and malignant tissues.5,14-16 GDF15 induced AKT activation in NCI-H929 cells as evidenced by increased levels of phosphorylated AKT (Figure 2A), and the AKT inhibitor (Akti)-1/2 (124018) significantly blocked the ability of GDF15 to enhance colony formation (Figure 2B, first plating; 100 nM, P = .020, 1 uM, P = .0066, second plating; 100 nM, P = .0089, 1 uM, P = .0037). We also examined the transcription factor SOX2 because it can be activated by AKT and is involved in the pluripotency and self-renewal of ES cells and induced pluripotent stem cells.17-19 Moreover, SOX2 expression increases during the transition from asymptomatic monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS) to overt MM.20 GDF15 increased the expression of SOX2 in NCI-H929 MM cells (Figure 2A), and this induction could be inhibited by treatment with Akti-1/2 (Figure 2C). Furthermore, decreased SOX2 expression using siRNA significantly limited the GDF15-induced enhancement of colony formation (Figure 2D). In addition, AKT and SOX2 inhibition similarly inhibited the clonogenic growth of RPMI 8226 cells (supplemental Figure 2). We also examined the effects of GDF15 on the expression of BMI-1, a member of the polycomb-repressive complex 1 required for the self-renewal of normal adult stem cells.21,22 In MM, BMI-1 is similarly required for clonogenic MM growth,23 and we found that its expression was induced by GDF15 (Figure 2A). Taken together, these results indicate that GDF15 enhances clonogenic MM growth through key factors regulating self-renewal.

GDF15 activity is dependent on AKT and SOX2. (A) Western blot detection of phosphorylated AKT, BMI-1, and SOX2 expression by NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF (100 ng/mL). (B) Serial colony formation after treatment with GDF15 and the Akti 124018 for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15. (C) Western blot analysis of SOX2 after treatment with GDF15 and AKT inhibitor. (D) Serial colony formation of NCI-H929 cells after transfection of SOX2 or control short interfering RNA (siRNA) and treatment with GDF15 for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with scramble control and 0 ng/mL GDF15. The inset shows SOX2 expression by qRT-PCR 3 days after transfection.

GDF15 activity is dependent on AKT and SOX2. (A) Western blot detection of phosphorylated AKT, BMI-1, and SOX2 expression by NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF (100 ng/mL). (B) Serial colony formation after treatment with GDF15 and the Akti 124018 for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15. (C) Western blot analysis of SOX2 after treatment with GDF15 and AKT inhibitor. (D) Serial colony formation of NCI-H929 cells after transfection of SOX2 or control short interfering RNA (siRNA) and treatment with GDF15 for 3 days. *P < .05 compared with scramble control and 0 ng/mL GDF15. The inset shows SOX2 expression by qRT-PCR 3 days after transfection.

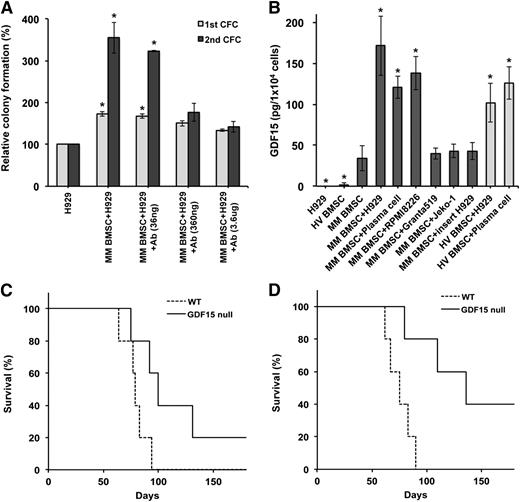

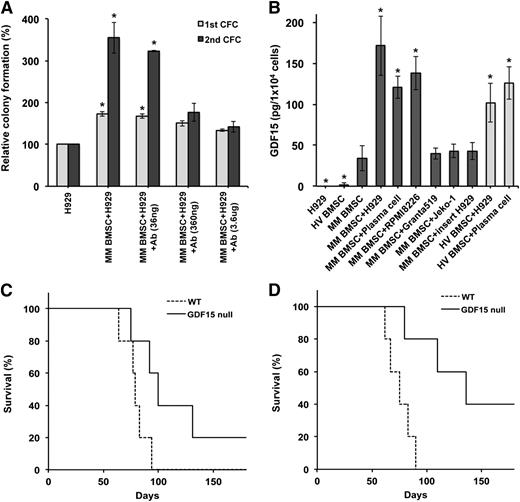

BMSC–derived GDF15 enhances clonogenic myeloma growth

BMSCs promote drug resistance and tumor cell survival in MM, but their impact on tumor initiation and self-renewal is not well understood. We cocultured NCI-H929 cells with BMSCs isolated from MM patients and found that both primary and secondary colony formation were significantly increased compared with MM cells cultured alone (Figure 3A). To determine whether GDF15 mediates this interaction, we treated cocultures with a neutralizing anti-GDF15 antibody and found that it modestly affected initial colony formation compared with an isotypic control antibody. However, the anti-GDF15 antibody significantly inhibited secondary colony formation at the 2 highest doses (P = .004), suggesting that BMSC-derived GDF15 primarily enhances the self-renewal of MM cells.

BMSC-derived GDF15 enhances clonogenic MM growth. (A) Serial colony formation by NCI-H929 cells cocultured with MM BMSC in the presence or absence of anti-GDF15 antibody (Ab) for 4 days. *P < .05 compared with NCI-H929 cell only. (B) GDF15 secretion by primary BMSCs derived from HVs (light gray) and MM patients (dark gray) cultured alone or with NCI-H929 (H929), Granta519, Jeko-1, or normal CD138+ plasma cells. Cell culture inserts inhibited cell-cell contacts between NCI-H929 cells and MM BMSCs. *P < .05 compared with MM BMSC only. (C) Survival of Gdf15null or wild-type (WT) mice after injection of Vk*Myc MM cells (n = 5 for each group). (D) Secondary transplantation of BM derived from mice initially engrafted with Vk*Myc MM cells.

BMSC-derived GDF15 enhances clonogenic MM growth. (A) Serial colony formation by NCI-H929 cells cocultured with MM BMSC in the presence or absence of anti-GDF15 antibody (Ab) for 4 days. *P < .05 compared with NCI-H929 cell only. (B) GDF15 secretion by primary BMSCs derived from HVs (light gray) and MM patients (dark gray) cultured alone or with NCI-H929 (H929), Granta519, Jeko-1, or normal CD138+ plasma cells. Cell culture inserts inhibited cell-cell contacts between NCI-H929 cells and MM BMSCs. *P < .05 compared with MM BMSC only. (C) Survival of Gdf15null or wild-type (WT) mice after injection of Vk*Myc MM cells (n = 5 for each group). (D) Secondary transplantation of BM derived from mice initially engrafted with Vk*Myc MM cells.

We also investigated the production of GDF15 by BMSCs and found that those isolated from MM patients secreted more GDF15 than BMSCs from healthy volunteers (HVs), as previously reported (Figure 3B),4 but these levels were significantly increased during cocultures with NCI-H929 cells (P < .03). BMSCs, rather than MM cells, were responsible for increased GDF15 production because they exclusively expressed GDF15 by qRT-PCR after coculture (supplemental Figure 3). Moreover, direct cell-cell contact was required because cell culture inserts separating the 2 cell types prevented increased GDF15 production (Figure 3B). Interestingly, normal plasma cells isolated from HVs also induced GDF15, whereas cocultures with Granta 519 and Jeko-1 mantle cell lymphoma cells that phenotypically resemble B cells did not induce GDF15 production.

To determine the effects of BMSC-derived GDF15 on in vivo tumor-initiating potential, we examined the engraftment of immunocompetent Gdf15−/− (null) or wild-type C57/Bl6 mice with tumor cells from Vk*Myc transgenic mice that develop plasma cell dyscrasias closely resembling human MM.24,25 The engraftment of GDF15 null mice was modestly decreased compared with wild-type recipients (Figure 3C; 80% vs 100%) but a significantly prolonged median survival was observed (79 vs 96 days, P < .05). We also carried out secondary transplants by injecting equal numbers of tumor cells isolated from GDF15 null or wild-type primary recipients into wild-type secondary recipients. The engraftment of tumor cells from GDF15 null primary recipients was significantly impaired compared with those from wild-type mice (Figure 3D; 60% vs 100%) and was associated with a significant prolongation of survival (136 vs 75 days, P < .002). Therefore GDF15 produced by BMSC in response to contact with plasma cells enhances the clonogenic growth and self-renewal of MM cells both in vitro and in vivo.

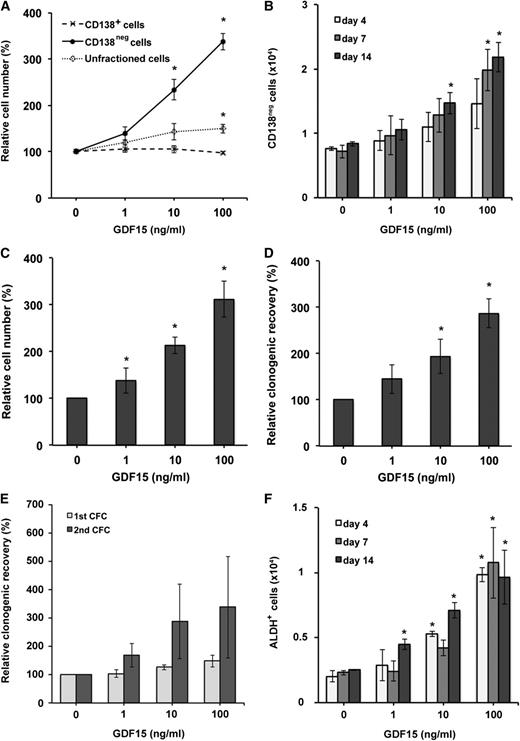

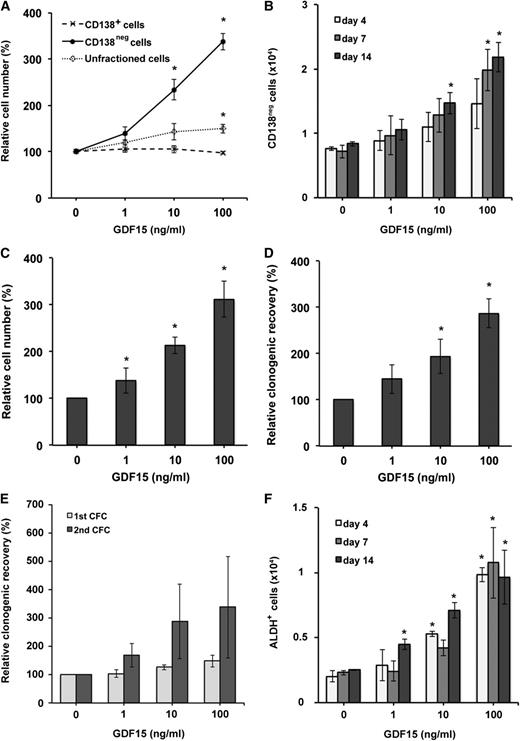

GDF15 enhances the clonogenic growth and self-renewal of phenotypically defined MM TICs

In many diseases, self-renewal is enriched within subpopulations of TICs that are phenotypically distinct from bulk tumor cells. Several methods have been used to identify tumorigenic MM cells, but the precise TIC phenotype has remained unclear.11,12,26,27 Normal and MM plasma cells uniformly display high levels of CD138 (Syndecan-1), but human MM cell lines and clinical specimens contain relatively small subpopulations that lack or express low levels of this surface antigen.11,12,20,26 We previously found that CD138neg MM cells give rise to CD138+ plasma cells and are enhanced for long-term tumor colony formation in vitro and engraftment in vivo.11,12 Similarly, increased ALDH expression may also identify highly tumorigenic and self-renewing MM cells similar to normal hematopoietic stem cells and TICs in breast and pancreatic carcinoma.12,28-30 To better characterize MM TICs, we compared the expression of CD138 and ALDH in NCI-H929 and RPMI 8226 cells. In each cell line, CD138neg and ALDH+ cells accounted for 1.43% to 1.77% and 2.17% to 2.53% of all cells, but these populations were not completely overlapping because 43% to 63% of the ALDH+ cells were also CD138neg (supplemental Table 1). We examined the engraftment of NSG mice with NCI-H929 and RPMI 8226 cells isolated based on CD138 or ALDH expression and found that the TIC frequency of CD138neg cells was significantly increased compared with CD138+ cells (Table 2 and supplemental Table 2; P < .000000093 and .0000069, respectively). Similarly, the TIC frequency of ALDH+ NCI-H929 and RPMI 8226 cells was significantly greater than ALDHneg cells (P < .00000021 and .0000015, respectively) but similar to CD138neg cells. Therefore human MM TICs can be enriched based on CD138 and ALDH expression.

To determine the impact of GDF15 on MM TICs, we isolated CD138neg cells from the NCI-H929 cell line and found that GDF15 significantly increased total cell numbers compared with vehicle-control–treated cells (Figure 4A; P < .014). To determine whether GDF15 induces the expansion of CD138neg NCI-H929 cells or their differentiation into CD138+ plasma cells, we examined CD138 expression by flow cytometry and found that GDF15 treatment significantly increased the absolute number of CD138neg cells (Figure 4B; P < .002). To more directly examine the impact of GDF15 on specific cell populations, we prospectively isolated CD138neg cells and found that GDF15 significantly expanded both the number of cells (Figure 4C; P = .03) and subsequent clonogenic growth (Figure 4D; P = .02). In contrast, GDF15 did not significantly alter the total cell number (Figure 4A; 10 ng/mL, P = .42; 100 ng/mL, P = .28) or colony-forming frequency of isolated CD138+ NCI-H929 cells compared with controls (Figure 4E; P > .06), consistent with previous findings that GDF15 increases the survival, but not proliferation, of MM plasma cells.5 Similarly, treatment of GDF15 did not change the clonogenic potential of CD138+ MM cells derived from primary clinical specimens (data not shown). We similarly found that GDF15 expanded CD138neg, but not CD138+, RPMI 8226 cells (supplemental Figure 4A-C). We also studied ALDH+ MM cells and found that GDF15 treatment significantly increased the absolute number of ALDH+ NCI-H929 (Figure 4F; P < .03) and RPMI 8226 cells (supplemental Figure 4; P < .04). Finally, we also examined the role of AKT and SOX2 on the expansion of MM cancer stem cells (CSCs) and found that the inhibition of AKT or knock-down of SOX2 inhibited the expansion of both CD138neg and ALDH+ cells by GDF15 (supplemental Figure 5A-B). Therefore GDF15 primarily expands MM TICs that are CD138neg or ALDH+ but has little effect on the proliferation or clonogenic growth of mature CD138+ tumor cells.

GDF15 expands MM TICs. (A) Relative cell numbers after treatment of unfractionated, CD138neg, and CD138+ NCI-H929 cells with GDF15 for 7 days. (B) Absolute number of CD138neg NCI-H929 cells quantified by flow cytometry after treatment with GDF15. (C) Relative expansion of prospectively isolated CD138neg NCI-H929 cells by GDF15. (D) Relative clonogenic recovery of CD138neg NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF15 for 7 days. (E) Relative clonogenic recovery of CD138+ NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF15 for 7 days. (F) Absolute number of ALDH+ NCI-H929 cells quantified by flow cytometry after treatment with GDF15. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15.

GDF15 expands MM TICs. (A) Relative cell numbers after treatment of unfractionated, CD138neg, and CD138+ NCI-H929 cells with GDF15 for 7 days. (B) Absolute number of CD138neg NCI-H929 cells quantified by flow cytometry after treatment with GDF15. (C) Relative expansion of prospectively isolated CD138neg NCI-H929 cells by GDF15. (D) Relative clonogenic recovery of CD138neg NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF15 for 7 days. (E) Relative clonogenic recovery of CD138+ NCI-H929 cells after treatment with GDF15 for 7 days. (F) Absolute number of ALDH+ NCI-H929 cells quantified by flow cytometry after treatment with GDF15. *P < .05 compared with 0 ng/mL GDF15.

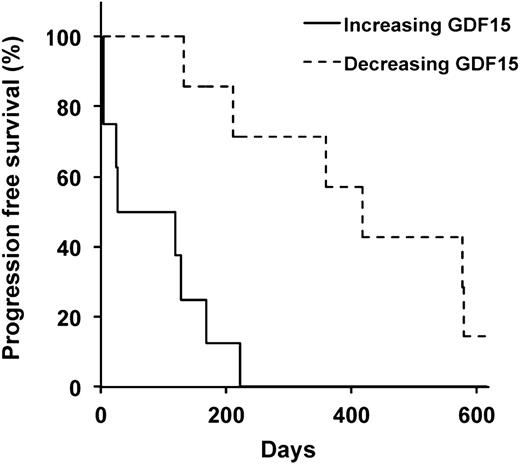

Serum GDF15 is associated with clonogenic tumor growth and clinical outcomes in MM

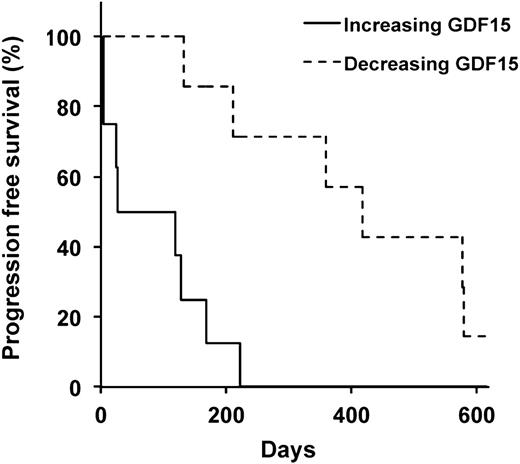

The clonogenic potential of TICs suggests they play an essential role in tumor regrowth; therefore changes in the frequency of TICs over time may correlate with clinical outcomes including disease relapse. We previously found that changes in MM colony formation after treatment with high-dose cyclophosphamide and rituximab were associated with progression-free survival.31 We quantified serum GDF15 levels in this cohort of patients and found that changes in GDF15 levels correlated with the differences in MM colony formation over the course of treatment in 12 of the 15 patients studied (80%; Figure 5, supplemental Figure 6, and supplemental Table 3; P = .026). We also examined the clinical relevance of changes in GDF15 levels and detected decreasing GDF15 levels in 7 of 15 (47%) patients over the course of treatment that were associated with a significantly longer progression-free survival compared with the remaining 8 patients with increasing GDF15 levels (Table 3; P = .0088). Therefore GDF15 levels may serve as a surrogate for the frequency of TICs, as well as predict disease relapse and progression in MM.

Serum GDF15 levels and clinical outcomes in MM. Progression-free survival of MM patients based on increasing or decreasing serum levels of GDF15.

Serum GDF15 levels and clinical outcomes in MM. Progression-free survival of MM patients based on increasing or decreasing serum levels of GDF15.

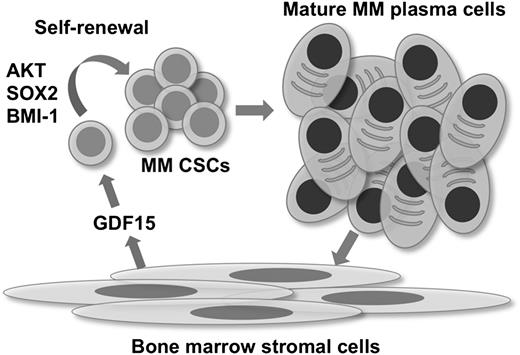

Discussion

CSCs have been functionally defined by the capacity to produce differentiated cells that recapitulate the original tumor in the ectopic setting and self-renewal to maintain long-term tumor-initiating potential.32 These properties suggest that the inhibition of CSCs may improve clinical outcomes, and several intrinsic pathways regulating their self-renewal have been identified.33 Less is known about the extrinsic factors that affect these cells, but we found that GDF15 aberrantly produced by BMSCs within the TME enhances serial tumor cell colony formation as well as primary and secondary MM engraftment in immunodeficient and immunocompetent mice. Therefore GDF15 may play an important role in the pathogenesis of MM through its effects on clonogenic growth and self-renewal.

As in most cancers, MM cells display both phenotypic and functional heterogeneity. The vast majority of tumor cells are plasma cells characterized by high surface expression of CD138, but several groups have identified relatively rare subpopulations of MM cells that lack or display low levels of this antigen.11,12,20,34-37 Functional heterogeneity also exists in MM, and only a fraction of cancer cells are capable of tumor initiation both in vitro and in vivo.38,39 MM cell phenotypes may be linked to their functional properties because CD138neg cells isolated from primarily clinical specimens exhibit enhanced clonogenic growth, give rise to mature CD138+ plasma cells, and maintain tumorigenic potential during serial transplantation in immunodeficient NOD/severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or NSG mice.11,12 The ability to undergo self-renewal and give rise to cells that histologically recapitulate the original tumor suggests that MM TICs are CD138neg, but tumor cells expressing CD138 or high levels of CD38, another marker of mature plasma cells, engraft human fetal bone fragments implanted in SCID (SCID-hu) mice.40-42 Moreover, in the 5T33 murine model of MM, both CD138neg and CD138+ cells are capable of clonogenic growth,43 whereas we have found that the engraftment potential of serially passaged tumor cells in the Vk*Myc model is limited to CD138+ cells (G.M., unpublished data). Putative human MM TICs have also been identified using the side population and Aldefluor assays, and these cell populations may or may not express CD138.12,26 Therefore the functional properties of MM cells may not be confined to a specific phenotypic population but may differ depending on disease stage or specific genetic mutations as described in chronic myeloid leukemia.44 We found that GDF15 preferentially induced the proliferation and expansion of CD138neg MM cells, but GDF15 has been found to induce the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9, which can cleave CD138 from the cell surface.45,46 Therefore it is possible that the increased numbers of CD138neg cells after GDF15 treatment reflects the loss of CD138 from the cell surface, but GDF15 also increased the number of ALDH+ TICs. Furthermore, GDF15 significantly inhibited serial colony formation in vitro and tumor engraftment in vivo using unfractionated cells, demonstrating that it affects these functional properties in MM regardless of the phenotype of the cell affected. We found that increased tumorigenic potential in response to GDF15 was increased to a greater extent in vivo than in vitro. Therefore, it is possible that GDF15 affects other cellular properties in addition to clonogenic growth, such as homing to the bone marrow or the expansion of tumor cells in vivo.

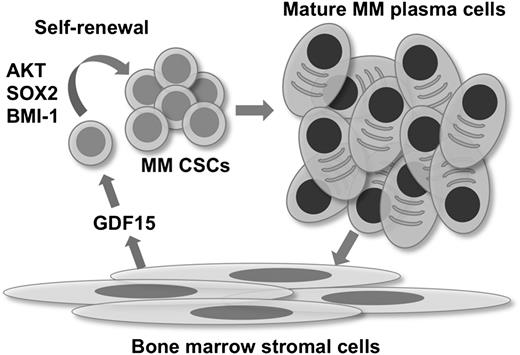

In contrast to epithelial cancers, in which tumor cells produce GDF15,47 MM is characterized by the aberrant secretion of GDF15 by BMSCs.4,5 Similar to previous findings,4 we found that BMSCs isolated from MM patients secreted higher baseline levels of GDF15 compared with normal donors. GDF15 secretion subsequently decreased with continued passaging, but could be re-induced by co-incubation with CD138+ plasma cells. Therefore the initial GDF15 secretion from MM patients is likely a result of interactions between BMSCs and MM plasma cell interactions in situ. We found that BMSCs increased the clonogenic potential of MM TICs, which was dependent on GDF15 because a neutralizing antibody significantly suppressed colony formation. Therefore the TME plays a significant role in regulating MM TICs. Based on these results, we propose a model in which plasma cells induce GDF15 secretion from BMSCs within the TME (Figure 6). GDF15 then activates signaling pathways that enhance the self-renewal and clonogenic potential of MM CSCs. These interactions generate a feed-forward loop that maintains the CSC pool and eventually generates additional MM plasma cells. A previous study found that BMSCs can induce CD138+ plasma cells to undergo de-differentiation to CD138neg cells.48 We did not observe changes in the expression of CD138 after the incubation of isolated CD138+ cells with GDF15, but it is possible that this effect is mediated by factors other than GDF15 or requires longer treatment periods. We found that a blocking antibody against GDF15 partially inhibited the interaction between MM cells and BMSCs, but it is likely that other cytokines are also involved. For example, it is well recognized that interleukin-6 is secreted by BMSCs, and we previously demonstrated that IL-6 can enhance MM clonogenic growth in vitro.49 Because GDF15 is elevated in a wide variety of inflammatory states that can lead to MGUS,50 it is also possible that these interactions play a role in the generation of MGUS and the subsequent transformation to MM.

Interactions between MM plasma cells, TICs, and BMSCs. The interaction between BMSCs and mature MM plasma cells induces GDF15 secretion and enhances the self-renewal of MM CSCs by AKT, SOX2, and BMI-1. Subsequent production of mature tumor cells further promotes this process.

Interactions between MM plasma cells, TICs, and BMSCs. The interaction between BMSCs and mature MM plasma cells induces GDF15 secretion and enhances the self-renewal of MM CSCs by AKT, SOX2, and BMI-1. Subsequent production of mature tumor cells further promotes this process.

Our findings may also have significant clinical implications. We found that relative changes in serum GDF15 levels over the course of treatment are significantly associated with progression-free survival. These data support previous findings that GDF15 levels in MM patients are associated with clinical outcomes, although the measurement of GDF15 was limited to a single time point in this study.5 We also found that serum GDF15 levels acutely increased after treatment with high-dose cyclophosphamide and then subsequently returned to lower levels. Because GDF15 is a p53 target gene,51,52 the acute elevation of serum levels may likely reflect cellular responses to cytotoxic treatment. We also found that GDF15 levels over the course of treatment paralleled changes in the frequency of MM colony formation. Therefore GDF15 may serve as a novel biomarker indicative of the frequency of MM TICs, although larger clinical studies are needed to confirm these results. Because the disruption of growth factor and cytokine signaling by neutralizing antibodies or small molecules is used in the treatment of many tumor types, targeting GDF15 activity may inhibit both the clonogenic potential of MM CSCs as well as the survival of mature plasma cells.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Suzanne Sebald and Se-Jin Lee for providing GDF15null mice. W.M. is a Scholar in Clinical Research of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R01CA127574 and R21CA155733 [W.M.]) and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (T32HL7525 [T.T.]).

Authorship

Contribution: T.T., Y.L., Q.W., and W.M. carried out the in vitro and in vivo studies; N.G., I.B., and C.A.H. were involved in specimen and clinical data collection; Q.W., M.C., P.L.B., G.M., and R.W.J. were involved in establishment of in vivo models of MM; and T.T. and W.M. wrote the manuscript with the assistance and final approval of all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for T.T. is Center for Cancer and Immunology Research, Children’s National Hospital, Washington, DC.

Correspondence: William Matsui, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, The Bunting Blaustein Cancer Research Building, Room 245, 1650 Orleans St, Baltimore, MD 21287; e-mail: matsuwi@jhmi.edu.