Key Points

Exome sequencing and functional studies identified RPS29 as a novel cause of autosomal dominant DBA.

DBA-associated mutations caused haploinsufficiency, a pre-rRNA processing defect, and defective erythropoiesis using an rps29−/− zebra fish model.

Abstract

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA) is a cancer-prone inherited bone marrow failure syndrome. Approximately half of DBA patients have a germ-line mutation in a ribosomal protein gene. We used whole-exome sequencing to identify disease-causing genes in 2 large DBA families. After filtering, 1 nonsynonymous mutation (p.I31F) in the ribosomal protein S29 (RPS29[AUQ1]) gene was present in all 5 DBA-affected individuals and the obligate carrier, and absent from the unaffected noncarrier parent in 1 DBA family. A second DBA family was found to have a different nonsynonymous mutation (p.I50T) in RPS29. Both mutations are amino acid substitutions in exon 2 predicted to be deleterious and resulted in haploinsufficiency of RPS29 expression compared with wild-type RPS29 expression from an unaffected control. The DBA proband with the p.I31F RPS29 mutation had a pre–ribosomal RNA (rRNA) processing defect compared with the healthy control. We demonstrated that both RPS29 mutations failed to rescue the defective erythropoiesis in the rps29−/− mutant zebra fish DBA model. RPS29 is a component of the small 40S ribosomal subunit and essential for rRNA processing and ribosome biogenesis. We uncovered a novel DBA causative gene, RPS29, and showed that germ-line mutations in RPS29 can cause a defective erythropoiesis phenotype using a zebra fish model.

Introduction

Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA; OMIM 105650) is a rare inherited bone marrow failure syndrome (IBMFS) occurring in ∼6 per 1 million live births.1 It is characterized by red blood cell (RBC) aplasia and variable congenital anomalies. DBA classically presents with severe anemia in the first year of life and may include craniofacial anomalies such as flat nasal bridge, high arched or cleft palate, and short stature.2 There is a high incidence of cancer in DBA patients, with particularly high risks of leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, colon adenocarcinoma, and osteosarcoma.3

DBA is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, although disease penetrance is often incomplete and expressivity may be variable, leading to clinical heterogeneity within families.4,5 DBA is considered a ribosomopathy, a disorder caused by impaired ribosome biogenesis and function, because the majority of DBA patients have a germ-line heterozygous mutation or deletion in a ribosomal protein (RP) gene.6 The most commonly mutated gene is RPS19, occurring in ∼25% of patients.7,8 Germ-line mutations in genes encoding components of both the small (RPS24, RPS17, RPS7, RPS10, and RPS26) and large (RPL35A, RPL5, RPL11, and RPL26) ribosomal subunits have also been described in DBA patients.1,9,10 Recently, mutations in the GATA1 gene, an X-linked hematopoietic transcription factor, were found to cause DBA in a minority of patients.11 However, because GATA1 has been implicated in DBA,11 it is possible that non-RP genes may also lead to the characteristic erythroid hypoplasia.

Zebra fish are ideal for modeling blood disorders because hematopoietic regulation is conserved in vertebrates, and they are amenable to high-throughput in vivo genetics. In addition, morpholinos can be used to transiently knock down genes in the embryo, and in vivo overexpression can be performed by injecting DNA or RNA.12 Here, we employed whole-exome sequencing (WES) to survey the exome for novel DBA disease-causing genes and used zebra fish as a model system to determine the consequences of the DBA-associated mutation. WES was performed on 13 individuals with DBA who lacked a mutation in any of the known DBA genes and family members from 2 large families with multiple DBA-affected individuals from the longitudinal IBMFS cohort at the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

Methods

Study population

Families with DBA were ascertained in NCI’s IBMFS cohort. The NCI IBMFS cohort is an open retrospective/prospective cohort study (www.marrowfailure.cancer.gov, NCI 02-C-0052, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier #NCT00027274) previously described13 and approved by the NCI Institutional Review Board. All patients and family members completed detailed family and medical history questionnaires, and we have conducted a thorough review of medical records, questionnaires, and clinical evaluations at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. DBA was diagnosed in individuals with macrocytic pure red cell aplasia and supported by finding increased erythrocyte adenosine deaminase (eADA).14 To date, 78 patients with DBA have been enrolled from 55 families. All DBA patients undergo routine clinical mutation testing for the 9 established RP DBA genes (RPS19, RPS24, RPS17, RPL35A, RPL5, RPL11, RPS7, RPS10, and RPS26). None of the patients reported in this study had a germ-line mutation in 1 of these genes.

Exome sequencing and analysis

DNA was extracted from whole blood using standard methods. WES for DBA families NCI-193 and NCI-38 was conducted at the NCI’s Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory as previously described.15 In brief, adapter-ligated genomic DNA libraries were prepared with the TruSeq DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then amplified by ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR), purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and evaluated electrophoretically. Exome enrichment was performed with NimbleGen’s SeqCap EZ Human Exome Library v2.0, targeting 44.1 Mb of exonic sequence (Roche NimbleGen Inc., Madison, WI). The exome-enriched libraries were amplified by ligation-mediated PCR, purified, and evaluated as previously. The resulting postcapture enriched multiplexed sequencing libraries were used in cluster formation on an Illumina cBOT, and paired-end sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq following Illumina-provided protocols for 2 × 100-cycle sequencing. Exomes were sequenced to sufficient depth to achieve a minimum threshold of 80% of coding sequence covered with at least 15 reads, based on University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) hg19 “known gene” transcripts. This minimum threshold resulted in an average coding sequence coverage of 160 reads. The human reference genome and the “known gene” transcript annotation were downloaded from the UCSC database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/), version hg19 (corresponding to Genome Reference Consortium assembly GRCh37). Alignments for each individual were refined using a local realignment strategy around known and novel sites of insertion and deletion polymorphisms using the RealignerTargetCreator and IndelRealigner modules from the Genome Analysis Toolkit (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/).16 Variant discovery and genotype calling of multiallelic substitutions, insertions, and deletions were performed on all individuals simultaneously using the UnifiedGenotyper module from Genome Analysis Toolkit with the minimum call quality parameter set to 30.

Annotation, fitting genetic models, and filtering of each variant locus were performed using a custom locally developed software pipeline using data from the UCSC GoldenPath database (http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/database/); the ESP6500 data set from the Exome Variant Server, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Exome Sequencing Project (ESP; http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/); the Institute of Systems Biology Kaviar (Known VARiants) database (http://db.systemsbiology.net/kaviar/)17 ; the National Center for Biotechnology Information dbSNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/)18 build 137; and the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org/).19 Variants were also annotated for their presence in an in-house database consisting of ∼1000 exomes that were sequenced in parallel with our DBA families. Variants within each family were filtered as indicated in supplemental Table 1 (see the Blood Web site).

Variant validation

Variants of interest were validated to rule out false-positive findings using an Ion 316 chip on the Ion PGM Sequencer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Primers for sequencing were designed using Primer3 software (http://jura.wi.mit.edu/rozen/papers/rozen-and-skaletsky-2000-primer3.pdf). The BLAT (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool [BLAST]-Like Alignment Tool) feature on the UCSC Genome Browser (ucsc.genome.edu) and NetPrimer software (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/netprimer/index.html) were used to evaluate sequence specificity and oligo folding irregularities. Primers were provided by IDT Technologies (Coralville, IA). All samples were amplified using KAPA2 RobustHotstart Readymix (2X; Kapa Biosystems, Johannesburg, South Africa) (primer sequences available upon request). Amplicons were purified using Agencourt’s Ampure XP beads, and then libraries were constructed and barcoded using the Ion Xpress Plus Fragment Library Kit (Life Technologies). DNA-tagged beads were generated for sequencing using Life Technologies’ OneTouch and run on an Ion 316 chip on the Ion PGM Sequencer (Life Technologies). The default torrent mapping alignment program aligner and variant caller were used to generate a variant list per sample.

In silico analysis

Polymorphism Phenotyping Version 2.2.2 (PolyPhen-2),20 Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT),21 Mutation Taster,22 and the likelihood-ratio test (LRT) were used to predict the functional impact of RPS29 amino acid substitutions. SiPhy,23 the Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP++) method,24 and Phylogenetic P values (PhyloP)25 were used to estimate the level of conservation at these sites; the larger these scores, the more conservation at the site. DbNSFP was used to compile the prediction scores from the following programs: Polyphen-2, SIFT, MutationTaster, LRT, SiPhy, GERP++, and PhyloP.26,27 The sitewise likelihood-ratio28 method was used to test for natural selection on the specific codons; a negative value suggests negative selection, and a positive value suggests positive selection. MUpro29 and I-Mutant Suite30,31 were employed to predict the protein stability changes and the sign and the value of free energy stability change, from the mutations in RPS29. Multiple sequence alignments were generated for homologous RPS29 protein sequences using T-Coffee32 to visualize conservation, and Jalview33 was used to format the alignments. Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Chimera package.34 Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at UCSF (supported by NIGMS P41-GM103311). The three-dimensional structure of the RPS29 protein was constructed from the structure of the human 40S RPs, Protein Data Bank ID 3J3A (chain d, 40S RPS29).35

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR

The complementary DNA (cDNA) was isolated from lymphoblasts and primary fibroblasts using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Life Technologies). Cells were grown using standard cell culture conditions. We designed TaqMan assays specific for the short or long isoform of RPS29. Assays were performed using TaqMan Fast Universal PCR Master Mix and 7900HT Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies). Primers for the short isoform were forward TCCGTCAGTACGCGAAGGATA, reverse CCGGATAATCCTCTGAAGGAAGA, and probe CGGTTTCATTAAGTTGGAC. Primers for the long isoform were forward CCGTCAGTACGCGAAGGATATC, reverse CCATAGGCAGTGCCAAGGAA, and probe TCATTAAGAAAGACCTGAGCTGT. Reactions were performed in triplicate for the lymphoblasts, and data from 2 cDNA preparations were combined for analysis using DataAssist Software, v3.01. The primary patient-derived fibroblasts did not grow well, and only a single reaction was performed. Four endogenous controls were used: ACTB, GAPDH, B2M, and 18SrRNA.

Pre-rRNA processing

Preparation of peripheral blood samples and Northern blot analyses using a hybridization probe to the internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) region of the polycistronic pre–ribosomal RNA (rRNA) transcript were performed as previously described.9

Zebra fish model

Zebra fish were maintained under approved laboratory conditions. The mutant zebra fish strain used in these studies, hi2903 (rps29−/−), has an insertion in the first intron of rps29.36 Rps29+/− fish were in-crossed to generate rps29−/− embryos, and homozygous mutants were confirmed by genotyping. Human wild-type (WT), p.I31F, or I50T mutant RPS29 cDNA was cloned into the pCRII TOPO vector (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY), linearized, and transcribed using mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was resuspended in nuclease-free water, and 50 pg of RNA was injected into rps29−/− embryos at the 1-cell stage. At 48 hours postfertilization, embryos were stained for hemoglobin (Hb) using benzidine, as previously described.37

Results

RPS29 germ-line mutations in DBA families

WES was performed on 2 families with multiple individuals affected with DBA (Table 1 and Figure 1) who were mutation-negative for the known DBA genes. The clinical characteristics and hematologic parameters of the individuals analyzed are summarized in Table 1. Because DBA is expected to be rare in an unaffected population, we filtered out variants that were present in the 1000 Genomes Project, ESP, or our internal control population.

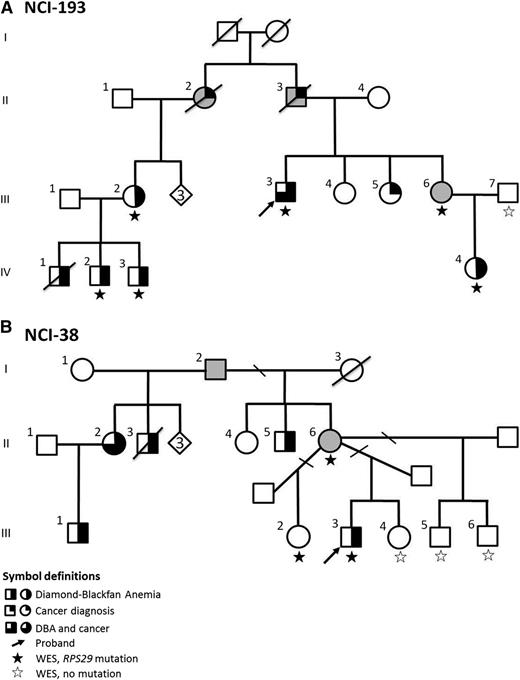

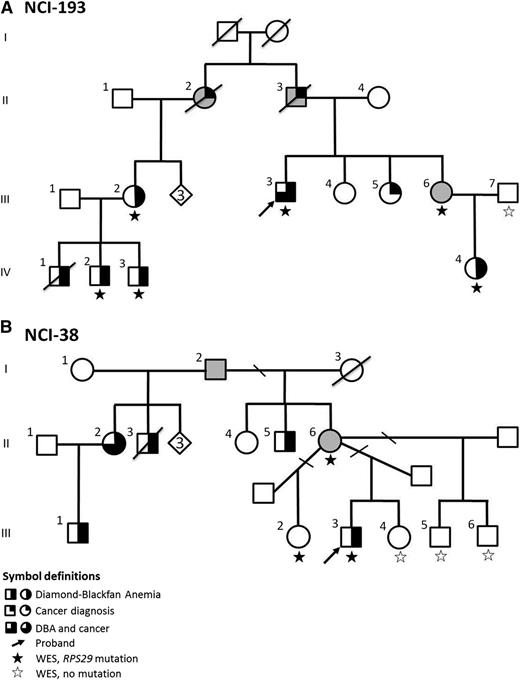

Pedigree of DBA Families. (A) Family NCI-193; (B) Family NCI-38. The diamond indicates the number of healthy siblings not shown.

Pedigree of DBA Families. (A) Family NCI-193; (B) Family NCI-38. The diamond indicates the number of healthy siblings not shown.

In family NCI-193 (Figure 1A), the male proband (III-3) had steroid-responsive anemia at age 9 years. He has 3 sisters: 2 are unaffected (III-4 and III-5); 1 is an OC (III-6) who has an elevated eADA (1.11 IU/g Hb, normal <0.96). Her daughter (IV-4) was diagnosed with steroid-responsive DBA at age 3 years. The proband’s paternal first cousin (III-2) had steroid-responsive DBA at 3 months of age, and her 3 male children (IV-1, IV-2, and IV-3) had DBA. In this family with 5 (living) clinically affected DBA cases, after filtering, only 1 variant was present in all cases (III-3, III-2, IV-2, IV-3, and IV-4) and the OC (III-6), and absent in the noncarrier unaffected family member (III-7; Figure 1 and Table 1): a novel mutation in RP S29 (RPS29, OMIM 603633). The nonsynonymous mutation in RPS29 is a heterozygous A to T transversion (chromosome 14, position 50 052 739) resulting in the substitution of isoleucine for phenylalanine at amino acid position 31 (p.I31F) (Table 2). This mutation has not been reported in any publicly available databases (ESP, 1000 Genomes Project, Kaviar, or dbSNP), and bioinformatic analyses predict that this mutation is deleterious for protein function (Table 2).

A second large family with DBA, NCI-38 (Figure 1B), was also evaluated by WES. The male proband (III-3) had steroid-responsive anemia at age 2 years and has been in remission for ∼20 years. He has 2 unaffected male half-siblings (III-5 and III-6) and 1 unaffected female full sibling (III-4) with no symptoms of DBA, as well as 1 asymptomatic female half-sibling (III-2) with only a borderline elevated eADA (1.00 IU/g Hb). Their mother (II-6) is an asymptomatic OC because her full brother (II-5), 2 half-siblings (II-2 and II-3), and niece (III-1) all had DBA. After filtering and applying an autosomal dominant inheritance model, WES in this family identified a second novel mutation in RPS29. The mutation was present in the proband (III-3), the OC mother (II-6), and the asymptomatic half-sibling with an elevated eADA (III-2), and absent in the 3 unaffected siblings with normal hematologic parameters (III-4, III-5, and III-6; Figure 1 and Table 1). This nonsynonymous RPS29 mutation is a heterozygous T to C transition (chromosome 14, position 50 052 681) resulting in the substitution of isoleucine for threonine at amino acid position 50 (p.I50T) (Table 2). p.I50T, like p.I31F, was not reported in any publicly available databases, and in silico prediction programs predict this mutation to be damaging (Table 2).

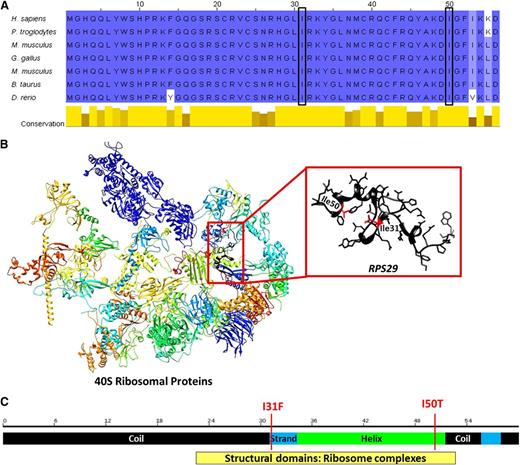

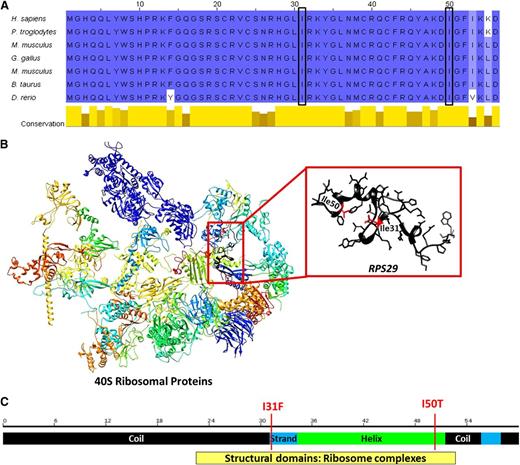

p.I50T and p.I31F mutations occur in exon 2 of RPS29 at a very highly evolutionarily conserved region predicted to be under strong negative selective pressure (Table 2 and Figure 2A), implying that variation in this region is likely deleterious. Both mutations occur in the important structural domain of the RPS29 protein and are predicted to decrease the stability of the protein structure (Table 2 and Figure 2B).

Diagram of RPS29 conserved domains and genomic structure. (A) Comparison of amino acid conservation of RPS29 homologs; a higher percent identity at a given position is indicated by a deeper blue color, and the 2 sites of mutation are indicated by the boxes. (B) The three-dimensional model of human 40S RPs35 and RPS29 (UniProt P62273, RS29_HUMAN) was constructed using the UCSF Chimera package.34 Secondary structural domains are shown as ribbons (α-helix; arrow is β-sheet, and tubes are loop regions), and the amino acid side chains of the RPS29 protein are illustrated. The sites of the amino acid substitutions are shown and highlighted in red. (C) Schematic of RPS29 secondary structure (black regions are coils, the green region is a helix, and blue regions are strands) with the sites of the amino acid substitutions shown.

Diagram of RPS29 conserved domains and genomic structure. (A) Comparison of amino acid conservation of RPS29 homologs; a higher percent identity at a given position is indicated by a deeper blue color, and the 2 sites of mutation are indicated by the boxes. (B) The three-dimensional model of human 40S RPs35 and RPS29 (UniProt P62273, RS29_HUMAN) was constructed using the UCSF Chimera package.34 Secondary structural domains are shown as ribbons (α-helix; arrow is β-sheet, and tubes are loop regions), and the amino acid side chains of the RPS29 protein are illustrated. The sites of the amino acid substitutions are shown and highlighted in red. (C) Schematic of RPS29 secondary structure (black regions are coils, the green region is a helix, and blue regions are strands) with the sites of the amino acid substitutions shown.

Haploinsufficiency of RPS29 expression and small subunit pre-rRNA processing defect

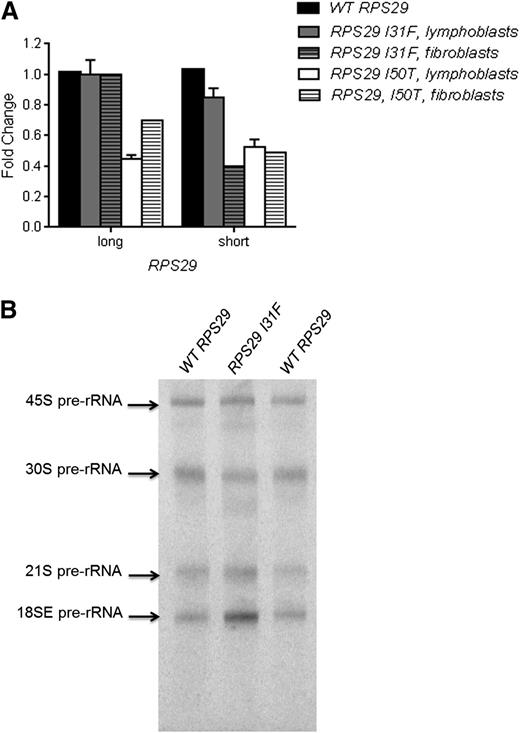

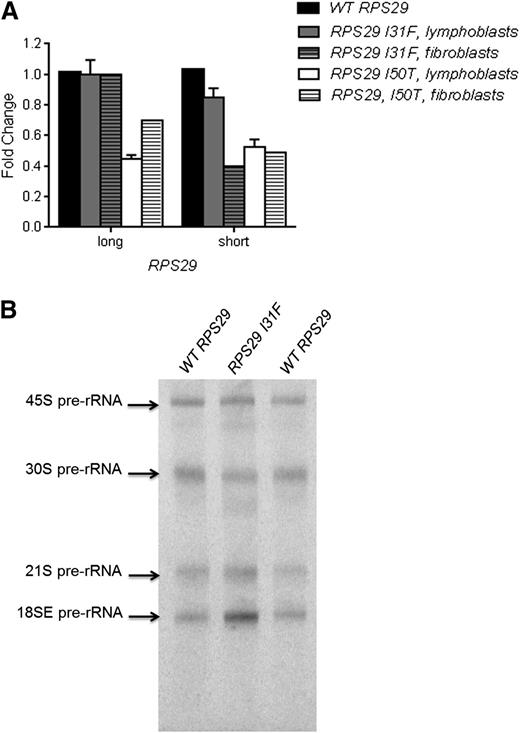

We used quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) to determine whether RPS29 expression was affected by the presence of the heterozygous p.I31F and p.I50T mutations. RPS29 has 2 isoforms, a short (56 amino acids; the canonical sequence) isoform and a long (67 amino acids) isoform, produced by alternative splicing. We examined the expression of both RPS29 isoforms in Epstein–Barr virus-immortalized lymphocytes and primary fibroblasts derived from the probands of both families and a healthy individual with WT RPS29. The proband in family NCI-38 (p.I50T) had a 49% and 51% reduction in expression of the short isoform in lymphoblasts and primary fibroblasts, respectively, and a 61% and 30% reduction of the long isoform of RPS29 in lymphoblasts and primary fibroblasts, respectively, compared with WT RPS29 values (P < .01; Figure 3A). The proband in family NCI-193 (p.I31F) had an 18% and 60% reduction in expression of the short isoform in lymphoblasts and primary fibroblasts, respectively, and did not show a reduction in expression of the long isoform of RPS29 (Figure 3A).

Functional assays for the RPS29 mutations. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for RPS29 expression was performed on peripheral blood–derived lymphoblasts and primary fibroblast RNA samples from the proband from family NCI-193 (p.I31F) and family NCI-38 (p.I50T) and an unaffected control individual WT RPS29. The figure shows the combined data from 3 plates for lymphoblasts, and data for 1 plate for the fibroblasts, normalized using 2 endogenous controls (ACTB and GAPDH), for the short and long isoforms of RPS29. (B) Northern blot analysis of pre-rRNA processing was performed with a hybridization probe to 18SE/ITS1 (probe γ) using activated lymphocytes9 recovered from the peripheral blood from the proband (III-3) in family NCI-193 (p.I31F) and an unaffected control individual with WT RPS29.

Functional assays for the RPS29 mutations. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR for RPS29 expression was performed on peripheral blood–derived lymphoblasts and primary fibroblast RNA samples from the proband from family NCI-193 (p.I31F) and family NCI-38 (p.I50T) and an unaffected control individual WT RPS29. The figure shows the combined data from 3 plates for lymphoblasts, and data for 1 plate for the fibroblasts, normalized using 2 endogenous controls (ACTB and GAPDH), for the short and long isoforms of RPS29. (B) Northern blot analysis of pre-rRNA processing was performed with a hybridization probe to 18SE/ITS1 (probe γ) using activated lymphocytes9 recovered from the peripheral blood from the proband (III-3) in family NCI-193 (p.I31F) and an unaffected control individual with WT RPS29.

We evaluated pre-rRNA processing in mononuclear cells from the proband in family NCI-193 (p.I31F) and a healthy individual with WT RPS29 to determine if the RPS29 mutation affected ribosome synthesis. The DBA proband clearly showed an increase in the 18SE pre-rRNA intermediate, and slightly increased 21S and lower 30S compared with the healthy individual (Figure 3B). These data showing that RPS29 is required for the maturation of the 3′ end of 18S rRNA are consistent with the known effect of reduced RPS29 expression on pre-rRNA processing in HeLa cells.38

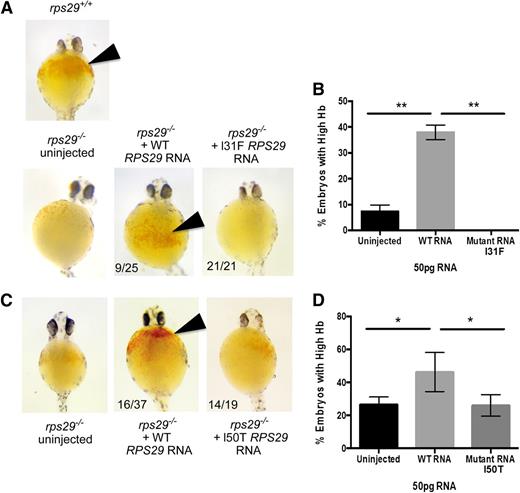

DBA-associated mutant RPS29 does not rescue the Hb defect in rps29−/− zebra fish

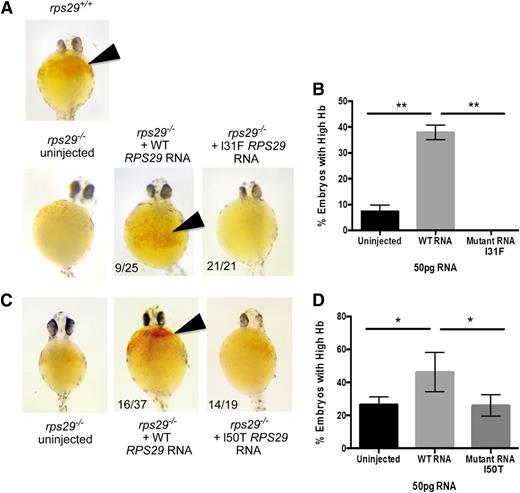

The rps29−/− mutant zebra fish has key features of the DBA phenotype including significant defects in RBC development,39 shown by a decrease in Hb levels. We used this as a model to determine whether the RPS29 mutation identified in our DBA cases could rescue the Hb defect. The rps29−/− zebra fish embryos were injected with either WT or the p.I31F mutated human RPS29 RNA. The WT human RPS29 RNA rescued the anemia phenotype of the rps29−/− zebra fish embryos, as shown by increased Hb levels, similar to the rps29+/+ phenotype (9/25 embryos; Figure 4A). All of the 21 rps29−/− zebra fish embryos injected with mutated human RPS29 RNA had very low Hb (no rescue; Figure 4A). The WT RPS29 RNA–injected rps29−/− zebra fish embryos had significantly greater rescue of the Hb phenotype compared with the embryos injected with the mutated (p.I31F) human RPS29 RNA and the uninjected rps29−/− embryos (Student t test P < .01; Figure 4B). Using the same assay, human RPS29 RNA containing the p.I50T mutation was injected into rps29−/− embryos. Similar to p.I31F, this mutant RNA was unable to rescue the high Hb phenotype seen when WT human RPS29 RNA is injected (Figure 4C). The percentage of embryos with high Hb levels was equal between uninjected and p.I50T-injected rps29−/− embryos, whereas the percentage in those embryos injected with WT human RPS29 RNA was significantly higher than both groups (Student t test P < .05; Figure 4D).

Zebra fish as a DBA model of the RPS29 mutations. (A) The Hb phenotype of zebra fish embryos with WT rps29+/+, rps29−/− uninjected embryos, rps29−/− embryos injected with WT human RPS29 RNA, and rps29−/− embryos injected with the p.I31F mutant human RPS29 RNA from the proband (III-3) in family NCI-193. The numbers of zebra fish embryos displaying this phenotype are shown (ie, 9 of 25 injected and 21 of 21 injected). (B) The percent of rps29−/− zebra fish embryos with high Hb are shown for the uninjected embryos, WT human RPS29 RNA–injected embryos, and the p.I31F mutant human RPS29 RNA–injected embryos. (C) The Hb phenotype of embryos injected with the p.I50T mutant human RPS29 RNA. (D) The percent of embryos with high Hb. *Student t test P < .05; **Student t test P < .01.

Zebra fish as a DBA model of the RPS29 mutations. (A) The Hb phenotype of zebra fish embryos with WT rps29+/+, rps29−/− uninjected embryos, rps29−/− embryos injected with WT human RPS29 RNA, and rps29−/− embryos injected with the p.I31F mutant human RPS29 RNA from the proband (III-3) in family NCI-193. The numbers of zebra fish embryos displaying this phenotype are shown (ie, 9 of 25 injected and 21 of 21 injected). (B) The percent of rps29−/− zebra fish embryos with high Hb are shown for the uninjected embryos, WT human RPS29 RNA–injected embryos, and the p.I31F mutant human RPS29 RNA–injected embryos. (C) The Hb phenotype of embryos injected with the p.I50T mutant human RPS29 RNA. (D) The percent of embryos with high Hb. *Student t test P < .05; **Student t test P < .01.

Discussion

The RPS29 gene encodes the 40S RP S29, which is a component of the small 40S ribosomal subunit and is essential for rRNA processing and ribosome biogenesis.38 We used WES to identify 2 novel mutations in RPS29 in 2 large multicase DBA families. Our functional studies show that these RPS29 mutations are pathogenic and result in anemia. The mutations in these families are nonsynonymous amino acid substitutions in exon 2 that are predicted to be deleterious to the structure and function of the protein. We have shown that the RPS29 mutations in both families (p.I31F and p.I50T) lead to an ∼50% expression of the canonical isoform of RPS29, showing that expression from the mutated allele is lost, and we showed a pre-rRNA processing defect in the DBA proband in family NCI-193 (p.I31F), indicating a defect in ribosome synthesis in the patient with this RPS29 mutation. We further demonstrated that both RPS29 mutations did not rescue the Hb defect in rps29−/− zebra fish. This discovery adds another RP gene to the growing list of mutated genes in DBA patients and supports DBA as a disorder of ribosomes.

RPS29 was previously identified to be required for definitive erythropoiesis in a zebra fish embryo, as rps29−/− mutants have many aspects of the DBA phenotype.39 These include decreased hematopoietic stem cell markers, defects in RBC development, and an increase in apoptotic cells.12,39 Here we show that both our DBA-associated RPS29 mutations failed to rescue the defective Hb levels in the rps29−/− zebra fish compared with WT human RPS29. This assay has some technical limitations, which can explain why the rescued phenotype is only seen in 40% of the WT human RPS29 RNA–injected embryos. These technical limitations include the stability of the RNA throughout the time of injection and the quality of each clutch of embryos (∼6-9 different clutches were used per mutation). Additionally, the translation of the RNA varies among the embryos. Although the RNA is initially injected into 1 cell, and thus should be in every cell, it may be diluted as the cells divide and the embryo grows. Each embryo injection may deliver slightly different amounts of RNA. Despite these limitations, the WT human RPS29 RNA was able to significantly increase the percentage of embryos with higher Hb levels at a rate similar to other human cDNA rescue experiments. Notably, neither of the RPS29 mutants was able to increase the proportion of embryos with high Hb compared with the uninjected controls. This provides evidence that RPS29 is required for normal erythropoiesis and supports that RPS29 is a DBA-associated gene.

Prior work with the rps29 mutant zebra fish model identified a link between rps29 and p53 (tumor suppressor gene TP53), showing that p53 activation results from rps29 deficiency and mediates the hematopoietic phenotype.12 Similarly, the rps19 zebra fish DBA model and mouse models also show that ribosomal haploinsufficiency results in p53 activation that leads to the defective erythropoiesis underlying the DBA-associated anemia.40,41 Together with the DBA-associated RPL5, RPL11, RPS7, RPL26, and RPS19 genes that have been shown to induce p53, RPS29 is an additional DBA gene linked to p53 activity. Zebra fish with heterozygous mutations in RP genes, including RPS29, were shown to have a loss of p53 synthesis as well as an elevated incidence of cancer.42,43

There were individuals with cancer in both families including the OCs with no DBA phenotype. In family NCI-193, the proband had lung cancer (age 56), his father (II-3; OC) had lung cancer (age 70), the proband’s paternal aunt (II-2; OC) had colon cancer (age 55), and his paternal first cousin (unaffected daughter of II-2, unknown carrier status but in bloodline) had cervical (in her 20s) and lung (age 49) cancers. In family NCI-38, the proband’s maternal (half-) aunt with DBA (II-2) had cervical cancer (age late 30s), and the proband’s maternal grandfather’s (I-2) sister had breast cancer (age 64, unknown carrier status but in bloodline). The affected individuals did not have DBA-associated dysmorphic features in these 2 families. Except for the proband with lung cancer and a transfusion-dependent individual in family NCI-193, all affected individuals had elevated eADA consistent with DBA. The asymptomatic OC (III-6) in family NCI-193 and an asymptomatic mutation carrier (III-2) in family NCI-38 also had an elevated eADA. Both families carried heterozygous RPS29 mutations inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion and had several OCs, indicating incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity of RPS29 mutations.

In summary, WES has allowed us to uncover a novel DBA causative gene, RPS29. We have determined that germ-line mutations in RPS29 can cause autosomal dominant DBA. Using functional assays, we show for the first time that the mutant RPS29 in our DBA cases results in haploinsufficiency of RPS29 and a small subunit pre-rRNA processing defect. The patient-associated RPS29 mutations failed to rescue the defective erythropoiesis in the rps29−/− mutant zebra fish DBA model and provide further evidence that RPS29 is required for normal erythropoiesis and is a DBA-associated gene.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the study participants for their valuable contributions. Lisa Leathwood, Westat Inc., provided excellent study support. The authors thank the NCI Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG) Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory and the NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group for participation in this study.

This study was funded by the intramural research program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, NCI, National Institutes of Health (NIH); Westat Inc. (contracts N02-CP-91026, N02-CP-11019, and HHSN261200655001C); the NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (training grant T32HL116324) (E.R.M.); NIH National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (5P30 DK049216-20); NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5U01HL10001-05); and a grant from the Diamond Blackfan Anemia Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A.S. and L.M. carried out project design; L.M. performed analyses; N.G. and B.P.A. performed clinical characterization and sample collection; M.Y., J.F.B., J.H., B.D.H., and L.B. performed sequencing and validation; E.R.M., A.M.T., K.E.M., J.M.H., and L.Z. performed zebra fish assays; L.J. and T.M. performed quantitative RT-PCR assays; S.R.E. performed pre-RNA processing; L.M. and S.A.S. wrote the manuscript; and all coauthors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.Z. is a founder and stockholder of Fate Inc., a founder and stockholder of Scholar Rock, and a scientific advisor for Stemgent. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sharon A. Savage, Clinical Genetics Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, NCI, 9609 Medical Center Dr, Room 6E454, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: savagesh@mail.nih.gov.