Abstract

Introduction: The thrombotic microangiopathies (TMA) thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) are virtually indistinguishable by clinical characteristics. However, their distinct pathophysiology and differential response to plasma exchange (PEx) or anti-C5 complement therapy demands an accurate diagnosis. ADAMTS13 activity <5-10% defines TTP in the majority of instances, but is complicated by the fact that the test is often not ordered prior to institution of PEx, and recent reports of TMAs characterized by ADAMTS13 <5% and high titer IgG that were refractory to PEx but responses to anti-complement therapy complicates the diagnostic dilemma. Elevated levels of terminal complement components (TCCs) C5a and C5b-9 (membrane attack complex, MAC) have been reported in both TTP and aHUS, and recent studies also suggest higher levels of C5b-9, in aHUS compared to TTP. This finding might explain differences in pathophysiology between subtypes of TMAs related to production of TCCs.

Objective: We sought to explore the levels of plasma TCCs, including C5a and C5b-9 in TMA subtypes as defined by several different criteria. We hypothesized that they are elevated in both TTP and aHUS-like TMAs, but at significantly higher levels in the latter, and would decline in TMAs in remission, but not normalize.

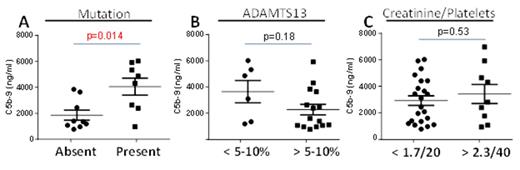

Methods: Blood collected by venipuncture into heparin sodium tubes from acute TMA patients, both primary (no accompanying diagnosis) and secondary (transplant, drug and cancer related cases) (n=44), TMA patients in remission (n=7) and controls. TMA subtypes were categorized by (1) physician clinical diagnoses (TTP n=28, aHUS n=9); (2) ADAMTS13 levels <5-10% (defining TTP, though timing of ADAMTS13 sampling and PEx initiation could not be certified in all cases); (3) initial platelet count and creatinine levels (“TTP” characterized as presenting platelet count <20,000 and/or creatinine <1.7); and (4) presence of germline complement or complement regulatory protein mutations linked to aHUS. TMA remission was defined as platelet count recovery (>150K) and recovery of renal function to baseline off therapy for at least one month. Samples were assayed for C5a and C5b-9 by ELISA. Genomic DNA was isolated from plasmas and amplified by semi-nested PCR using primers to detect complement mutations as we have described previously.

Results: We found elevated plasma levels of C5b-9 in acute TMAs compared to adult controls (median 3255 ng/ml; range 772-8109 vs 440; range 218-1136; p= 0.005) and compared to remission TMAs (1638 ng/ml; range 344-2100; p=0.03). When C5b-9 levels were compared between the pre-defined groups, only C5b-9 levels between patients with and without a complement mutations were significant (p=0.014; Figure 1). C5a levels were elevated in all TMAs but could not distinguish between TMA subtypes regardless of definition. Irrespective of diagnosis, levels of C5b-9 decreased from acute TMA levels in remission but still remained elevated compared to cord blood controls (p=0.014).

Conclusions: Dysregulation of the alternative complement pathway resulting from genetic deficiency in complement regulatory factors results in elevated TCCs in all TMAs, but absolute levels help to identify a unique subset of aHUS-like TMA patients. Clinical impression, absolute platelet count and creatinine level, or ADAMTS13 activity did not predict the degree of TCC elevation. Elevated C5b-9 in remission TMAs may be related to persistent complement regulation defects. Whether plasma TCC elevation predicts a response to anti-complement therapies remains to be determined.

Chapin:Alexion: Honoraria; Novo-Nordisk: Honoraria. Laurence:Alexion : Honoraria, Research Funding, Speakers Bureau; Omeros: Research Funding.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.