In this issue of Blood, Byrd et al provide an important update on the prolonged efficacy and the limited and reducing toxicity of the single-agent Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma patients who are followed for a median time of 3 years from start of treatment.1

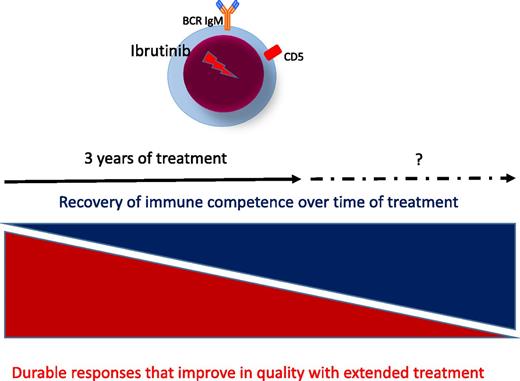

Consequences of prolonged treatment with ibrutinib in CLL. BCR, B-cell receptor.

Consequences of prolonged treatment with ibrutinib in CLL. BCR, B-cell receptor.

The study confirms and extends previous results2 but also adds new observations for future larger investigations, particularly in treatment-naïve patients. The data continue to demonstrate that ibrutinib promotes a high response rate that improves in quality with time, leading to durable remissions in all genetic subsets of CLL patients. Duration of responses appear dramatic in treatment-naïve patients, who carry a lower incidence of genetic damages than relapsed/refractory CLL patients.1 Unlike chemotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy regimens, which are given for a defined period because of limited tolerability, toxicities observed with continuous ibrutinib dosing appear modest, allowing most patients to remain on ibrutinib for an extended period (see figure).

One first important observation in this study is that quality of response gradually improves with duration of treatment. Ibrutinib induces death of 2.7% CLL cells per day in the lymph node, but a numerable fraction of cells is forced to exit and remain in the circulation.2-4 Ibrutinib is likely to interfere with other pathways associated with migration, adhesion, and egression.5 Inhibition in vitro occurs in those cells that have recovered from (super)antigen-induced anergy, and it is likely that the subgroup of cells with higher immunoglobulin(Ig)M and higher CXCR4 are those subject to ibrutinib-induced cell death.6

However, although immediate depletion of all CLL cells is not necessary, and best responses increase gradually during prolonged treatment, over 20% of treatment-naïve patients suspend therapy within the first months.1 Because the median overall survival of patients who discontinue ibrutinib has been reported to be 3 months,7 it will be very important to further characterize the features of those patients who stop treatment and to identify strategies to anticipate failure or discontinuation for any reason. The prolonged lymphocytosis induced during ibrutinib treatment does not appear to associate with an increased risk of progression1 ; however, those circulating cells may go back to tissue, and disease can become more aggressive when ibrutinib is discontinued.7 The majority of relapsed/refractory patients who discontinue ibrutinib harbor high-risk features, including del(17p) and/or a complex karyotype.7 However, little is known about the characteristics of treatment-naïve patients who suspend ibrutinib. It is of interest that the study by Byrd et al documents a different quality of response to ibrutinib in treatment-naïve patients with CLL carrying unmutated (U) or mutated (M) tumor immunoglobulin gene heavy-chain variable (IGHV) region (see supplemental Table 3 in the article by Byrd et al1 ). In the initial report in the PCYC-1102 (NCT01105247) trial for relapsed/refractory patients, the only factor associated with a different overall response rate to ibrutinib was tumor IGHV mutation status, because only 33% of CLL patients with M-IGHV (M-CLL) vs 77% of CLL patients with U-IGHV (U-CLL) obtained a response.2 Although these differences do not remain after 3 years of treatment of relapsed/refractory patients, quality of response appears remarkably higher in treatment-naïve patients with U-CLL (40% complete remission) vs M-CLL (6% complete remission).1 The number of treatment-naïve patients is small for conclusions (n = 31) but advocates further investigations with longer follow-up and larger cohorts.

Another important observation is the gradual decrease of infection complications during the 3 years of treatment, despite the persistence of circulating tumor cells. Interestingly, grade ≥3 infections are vritually absent in treatment-naïve patients.1 The authors point to the immune-modulating potential of ibrutinib through inhibition of interleukin-associated T-cell kinase, which can promote T helper cell type 1 CD4 T-cell outgrowth and diminish infection morbidity in animal models.1 However, CLL cells can act as regulatory B cells,8 and ibrutinib inhibits production of immunoregulatory interleukin-10 by activated CLL cells in vitro (Samantha Drennan and F.F., unpublished data, 2014). In addition, continuous treatment by ibrutinib was reported to associate with recovery of humoral immunity, with an increase in serum immunoglobulin levels, predominantly of the IgA isotype,2 but there is no mention of the serum immunoglobulin levels in this work with extended follow-up.1 The data leave the question on how ibrutinib favors immune recovery and set the basis for further investigation in larger cohorts of patients requiring treatment for the first time.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.