Key Points

Plasmodium vivax merozoites preferentially infect a subgroup of reticulocytes generally restricted to the bone marrow.

Accelerated “maturation” of infected reticulocytes.

Abstract

Plasmodium vivax merozoites only invade reticulocytes, a minor though heterogeneous population of red blood cell precursors that can be graded by levels of transferrin receptor (CD71) expression. The development of a protocol that allows sorting reticulocytes into defined developmental stages and a robust ex vivo P vivax invasion assay has made it possible for the first time to investigate the fine-scale invasion preference of P vivax merozoites. Surprisingly, it was the immature reticulocytes (CD71+) that are generally restricted to the bone marrow that were preferentially invaded, whereas older reticulocytes (CD71−), principally found in the peripheral blood, were rarely invaded. Invasion assays based on the CD71+ reticulocyte fraction revealed substantial postinvasion modification. Thus, 3 to 6 hours after invasion, the initially biomechanically rigid CD71+ reticulocytes convert into a highly deformable CD71− infected red blood cell devoid of host reticular matter, a process that normally spans 24 hours for uninfected reticulocytes. Concurrent with these changes, clathrin pits disappear by 3 hours postinvasion, replaced by distinctive caveolae nanostructures. These 2 hitherto unsuspected features of P vivax invasion, a narrow preference for immature reticulocytes and a rapid remodeling of the host cell, provide important insights pertinent to the pathobiology of the P vivax infection.

Introduction

The distinct tropism that different species of malaria parasites exhibit with respect to the red blood cell (RBC) fractions has a major impact on the course of infection and on the consequent pathology. Thus, the ability of Plasmodium falciparum to invade RBCs of all ages1 and the restriction of Plasmodium vivax to reticulocytes,2,3 are considered to contribute to their contrasting virulence. Although the predilection of P vivax for reticulocytes was first noted in the 1930s, the red cell components that determine this specificity remain unknown. The red cell Duffy receptor (DARC), a known receptor for P vivax invasion,4 is clearly not implicated because both reticulocytes and mature red cells (normocytes) express similar quantities of DARC on their surfaces.5 On the other hand, a family of Plasmodium merozoite proteins (reticulocyte binding proteins) that preferentially bind to reticulocytes has been identified,6 but the corresponding reticulocyte-specific receptors remain unknown. Thus, the detailed mechanism by which P vivax merozoites identify and invade human reticulocytes remains to be elucidated.

One of the factors that has frustrated efforts to identify the key reticulocyte receptor for P vivax is the significant heterogeneity of the “reticulocyte” populations, first classified by Heilmeyer in the 1930s.7 Reticulocytes mature to form normocytes over a 72-hour period, during which the reticulocytes produced by the expulsion of the nucleus from the normoblast undergo a series of dramatic biochemical, biophysical, and metabolic changes. The large globular and stiff nascent enucleated young reticulocyte sequentially ejects defunct organelles (reticular matter) and loses much of its membrane surface area. During maturation, there are particular subsets of receptors that are significantly depleted or completely eliminated predominantly by an exosome-dependent process.8 Notably, 1 such receptor, the transferrin receptor (CD71), is sequentially lost and becomes completely absent by the time the normocyte is formed,9-11 thus making it a useful biomarker for the fine-scale age-grading of reticulocytes.5,12,13 Most crucially, CD71 is depleted ∼20 hours before the last remnants of reticular matter (commonly detected by new methylene blue [NMB] or Thiazole Orange [TO] staining) are ejected; consequently, most reticulocytes (Heilmeyer stage IV) and normocytes circulating in the peripheral blood system are CD71−, whereas the majority of immature (CD71+) reticulocytes stages (Heilmeyer stages 0, I, II, and III) are confined to the bone marrow.14,15 Therefore, most studies on adult reticulocytes are in fact restricted to observations of the stage III reticulocytes, which are the first to emerge from the bone marrow, and stage IV CD71− reticulocytes.

Given that malaria parasites are observed not only in the peripheral blood but also in the bone marrow, investigations of the fine-scale tropism of P vivax merozoites must encompass all the stages of reticulocyte development. Ideally, one would assess the specificity of P vivax invasion using reticulocytes purified from bone marrow aspirates (which contain all reticulocyte developmental stages) as well as those from the peripheral blood. However, bone marrow aspirates are limited by practical and ethical considerations. One alternative is to use cord blood, which is relatively easy to procure and moreover yields significant quantities of nascent reticulocytes.16 Indeed, the use of fresh and frozen fetal reticulocytes isolated from cord blood has allowed the development of reliable P vivax invasion assays.17-19

To define the fine scale tropism of P vivax, we conducted ex vivo invasion assays on highly purified reticulocyte subsets (defined by TO staining and CD71 expression) isolated from cord blood. We further documented the remodeling of the reticulocyte following the invasion by the parasite. The observations derived from these investigations enhance our understanding of vivax malaria pathobiology and will facilitate the discovery of the reticulocyte receptor targeted by this important species of malaria parasite.

Methods

Ethics statement

The clinically infected RBC (IRBC) samples examined in this study were collected under the following ethical guidelines in the approved protocols; OXTREC 027-025 (University of Oxford, Centre for Clinical Vaccinology and Tropical Medicine, UK) and MUTM 2008-215 from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University. Research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Human parasites

Thirty-four clinical isolates of P vivax were collected from malaria patients receiving treatment at clinics run by the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit on the North Western border of Thailand. The project was explained to all the patients before they provided informed consent and before collection of blood by venipuncture. Five milliliters of whole blood were collected in lithium heparin collection tubes. These samples were cryopreserved in Glycerolyte 57 (Baxter) after leukocyte depletion using cellulose columns (Sigma, catalog #C6288).20 After thawing, the parasites present in the packed cells (1.5 mL per isolate) were cultured to the schizont stage in 12 mL of McCoy 5A medium supplemented with 2.4 g/L d-glucose, 40 mg/mL gentamycin sulfate, and 20% heat-inactivated human AB serum in an atmosphere of 5% O2 at 37.5°C.21

Magnetic and flow cytometry reticulocyte sorting

The depletion of the CD71+ reticulocytes was performed using the MACS system (Miltenyi, Singapore). One to 2 mL of blood at 50% hematocrit in phosphate-buffered saline were passed through the LS column, the purity of the positive and negative fractions was monitored by flow cytometry using TO staining. The yield of a CD71+ cell is upper 80% of purity.

The different fraction of reticulocytes: TO−, TOlow, and TOhigh (CD71+), were sorted using Influx or FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson) from 25 μL of cord blood. Three million reticulocytes were sorted for each of the subsets for the experiment based on CD71/TO staining (Figure 1B), and 1.5 million reticulocytes for each of the CD71 subsets (Figure 1D) were mixed with schizonts at a ratio of 6 to 1. For the 5 invasion experiments quantified by flow cytometry (Figure 1E-F), 24 million of cells were mixed with ∼250 000 P vivax schizonts.

Reticulocyte tropism of P vivax is restricted to CD71+ reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD71 and TO staining used to define the different erythrocyte subsets: TO+/CD71+ for the immature reticulocytes (green box), TOlow/CD71− for the mature reticulocytes (red box), and TO−/CD71− for the normocytes (black box). The insets on the right show the NMB-stained reticulocytes sampled from these gates by flow cytometry sorting. (B) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for normocytes (TO−/CD71−) (mean 2.17 ± 1.23 standard deviation [SD] vs 9.47 ± 4.81 SD), for the 3 reticulocyte subsets harvested by cell sorting. Bar represents 8 μm. (C) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the reticulocyte sampling based on the CD71 expression (CD71−, CD71low, CD71medium, CD71high). The top insets show each population stained by NMB. Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. (D) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for the CD71− population and for the 3 younger reticulocyte populations (mean CD71low: 5.09 ± 1.75 SD; CD71medium: 6.53 ± 2.41 SD; CD71high: 7.94 ± 3.14 SD; n = 3). Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. Bar represents 8 μm. (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing Hoechst and ethidium levels observed at the start (0 hours) and after 24 hours of the reinvasion assay with CD71− erythrocytes, and CD71+ reticulocytes treated or not with anti-Duffy antibodies. For the 0-hour data, the black thick-lined squares show the percentage of schizonts; the black thin-lined squares show the percentage of rings before invasion. For the 24 hours of data, the black thin-lined squares at 24 hours show the percentage of unburst schizonts; the orange thick-lined squares show the percentage of rings after invasion. (F) The percentage of rings after reinvasion (n = 5). The value observed with CD71+ reticulocytes incubated with anti-Duffy antibodies was taken as the threshold of reinvasion (0.74%). hr, hour. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Reticulocyte tropism of P vivax is restricted to CD71+ reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD71 and TO staining used to define the different erythrocyte subsets: TO+/CD71+ for the immature reticulocytes (green box), TOlow/CD71− for the mature reticulocytes (red box), and TO−/CD71− for the normocytes (black box). The insets on the right show the NMB-stained reticulocytes sampled from these gates by flow cytometry sorting. (B) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for normocytes (TO−/CD71−) (mean 2.17 ± 1.23 standard deviation [SD] vs 9.47 ± 4.81 SD), for the 3 reticulocyte subsets harvested by cell sorting. Bar represents 8 μm. (C) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the reticulocyte sampling based on the CD71 expression (CD71−, CD71low, CD71medium, CD71high). The top insets show each population stained by NMB. Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. (D) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for the CD71− population and for the 3 younger reticulocyte populations (mean CD71low: 5.09 ± 1.75 SD; CD71medium: 6.53 ± 2.41 SD; CD71high: 7.94 ± 3.14 SD; n = 3). Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. Bar represents 8 μm. (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing Hoechst and ethidium levels observed at the start (0 hours) and after 24 hours of the reinvasion assay with CD71− erythrocytes, and CD71+ reticulocytes treated or not with anti-Duffy antibodies. For the 0-hour data, the black thick-lined squares show the percentage of schizonts; the black thin-lined squares show the percentage of rings before invasion. For the 24 hours of data, the black thin-lined squares at 24 hours show the percentage of unburst schizonts; the orange thick-lined squares show the percentage of rings after invasion. (F) The percentage of rings after reinvasion (n = 5). The value observed with CD71+ reticulocytes incubated with anti-Duffy antibodies was taken as the threshold of reinvasion (0.74%). hr, hour. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Parasitemia and parasite sorting by flow cytometry

The parasitemia following reinvasion in the assays using CD71− and CD71+ reticulocytes was monitored by flow cytometry using the technique described previously.22 Human parasites were sorted using the technique adopted from Malleret et al22 using Hoechst (Sigma) and CD71 PE (Becton Dickinson) from 25 μL of infected blood samples. Cell sorting was performed using FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson).

Optical microscopy

Microscopic enumeration of IRBCs was performed using thin blood smears stained with Giemsa. A minimum of 4000 RBCs were counted (20 fields at 100× magnification). Live cell subvital staining of reticulocytes and of parasites was done using Giemsa or NMB.23

AFM and electron microcopy

At the designated time point, the IRBCs were harvested and processed and prepared as smears (unfixed and air dried) for atomic force microscopy (AFM) as previously described.24,25 A copper microdisc grid (H7 finder grid, SPI Supplies, PA) attached underneath the glass slide to allow colocation when later imaging cells of interest.

Thin smears were AFM scanned by a Dimension 3100 model with a Nanoscope IIIa controller (Veeco, Santa Barbara, CA) using tapping mode. The probes used for imaging were 125 µm long × 30 µm wide single-beam shaped cantilevers (model PPP-NCHR-50, Nanosensors) with tip radius of curvature of 5 to 7 nm. Images were processed and measurements were carried out using the Nanoscope 5.30 software (Veeco).

Electron microscopy was conducted on reticulocytes and IRBCs using the methods outlined in Malleret et al.5

Confocal microscopy and western blot

After AFM scanning, immunofluorescent assay detection of caveolin-1 was conducted on the isolates after cold acetone fixation. The primary antibodies used were caveolin-1 (#C4490, Sigma).After the addition of a second antibody (anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G fluorescein isothiocyanate [green] or Alexa 568 [red], Invitrogen) the fluorescence images were obtained using a confocal microscope (Olympus FluoView FV1000).

For the western blot, the RBC lysis and immunoblotting method was modified from Hanahan et al26 (anti-caveolin-1 [#C4490, Sigma], diluted at 1:1000).

Micropipette aspiration

The micropipette aspiration technique was modified from Hochmuth et al.27 Briefly, 1 µL of packed RBCs containing 0.5% to 1% IRBCs were resuspended in 1 mL 1× phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin. The samples were loaded into a sample chamber and mounted onto the Olympus IX71 Inverted Microscope. A borosilicate glass micropipette (∼1.5 inner diameter) was used to extract the cell membrane shear modulus by the micropipette aspiration technique. Single cells were aspirated under a negative pressure at a pressure drop rate of 0.5 Pa/s. The cell membrane shear modulus was calculated using the hemispherical cap model.27

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism (5.1). Median values were compared nonparametrically using a Kruskal-Wallis test, with Dunn’s test for post hoc analysis. Means compared by analysis of variance and Tukey’s multicomparison test.

Results

P vivax reticulocyte tropism

We first sought to determine whether the age of the reticulocytes affects their receptiveness to invasion by P vivax. It is known that all reticulocytes contain RNA and thus are stained by TO+; however, only the immature reticulocytes (Heilmeyer class I to III) are CD71+.5 Furthermore, whereas 60% of the reticulocytes in the peripheral circulation (Heilmeyer class IV) no longer express CD71, they still retain some residual RNA (TOlow).28 Normocytes (mature erythrocytes) are negative both for CD71 and for RNA staining (TO− and CD71−). Thus, using these 2 markers (TO and CD71), we were able to sort the RBCs from cord blood samples into 3 broad age groups (Figure 1A): immature reticulocytes TO+/CD71+), mature reticulocytes (TOlow//CD71−), and normocytes (TO−/CD71−). These 3 erythrocytic subsets were then used in a standardized P vivax reinvasion assay modified to use cryopreserved isolates and magnetically enriched schizonts.18 The schizont preparation was added to equal numbers of the RBC fractions sorted as described previously. After an incubation period of 24 hours, the newly infected RBCs were quantified by fluorescent and light microscopy (Figure 1B). Although a small number of invasions was observed in the normocytes (TO−/CD71−) and mature reticulocytes (TOlow/CD71+), most of the invasions were observed in immature reticulocytes (TO+/CD71+)(P < .05) (Figure 1B).

The distinct preference for immature reticulocytes indicated by this experiment prompted an invasion assay using more finely defined reticulocyte subsets, which were obtained as 4 populations defined by the level of CD71 expression (CD71−, CD71low, CD71medium, CD71high). The substantial chemical and mechanical differences between these reticulocyte subsets have been described recently by Malleret et al.5 Indeed, mere microscopic examination of subvitally stained reticulocytes from each of these 4 groups is sufficient to distinguish them, as is evident from the dark-staining reticular content and the clumping that are particularly evident in the CD71medium and CD71high nascent reticulocytes (Figure 1C). However, the reinvasion assays did not reveal any statistically significant differences in the reinvasion efficacy for the 3 CD71+ subsets, although there was a tendency for higher P vivax reinvasion with increasing CD71 levels (Figure 1D). We excluded CD71 as a receptor for P vivax invasion because in assays conducted in the presence of anti-CD71 monoclonal antibodies or with trypsinized reticulocytes (CD71 is trypsin-sensitive), the invasion efficacy was not altered.18

The experiments described rely on cell sorting, are expensive, and provide limited quantities of reticulocytes. We remedied this obstacle by immunomagnetic sorting of Percoll-enriched reticulocytes labeled with anti-CD71 antibodies, yielding relatively large volumes of CD71− and CD71+ fractions. We further achieved an improved quantification of invasions by using a flow cytometry approach22 that uses an anti-DARC antibody to define the threshold level of significant invasion (Figure 1E). Using this new rationalized protocol, we could clearly confirm the distinct tropism of P vivax for immature reticulocytes in 5 independent trials (P < .001) (Figure 1F).

Rapid remodeling of P vivax–infected reticulocytes

Given the distinct preference of P vivax for immature reticulocytes, we hypothesized that the ring-stage parasites from P vivax–infected patients would be predominantly CD71+. Unexpectedly, when P vivax–infected RBCs from 13 distinct isolates were analyzed, the majority (an average of 83.0% ± 10.8%) were in fact CD71− (Figure 2A-B). To better understand this phenomenon, the P vivax CD71+ and CD71− rings were then sorted by flow cytometry using DNA quantity (Hoechst signal) and CD71 expression (Figure 2C); their morphology was compared by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Whereas the surface of the CD71+P vivax rings was scattered with globular excrescences, they were almost completely absent from the surface of the CD71−P vivax rings (Figure 2C). In maturing uninfected reticulocytes, the disappearance of CD71 from the surface only occurs after 24 hours of maturation, whereas ejection of the reticular material is only completed about 16 hours later (ie, after 40 hours of maturation).5,15 Thus, a possible explanation for the stark contrast between the CD71+ and CD71− rings is that invasion by P vivax may induce or hasten the ejection of host cell material (including CD71) from the invaded reticulocyte. This hypothesis was supported in a series of ex vivo invasion assays in which P vivax–infected reticulocytes were harvested close to the time of invasion (0 hours) and then about 3 hours later; both subsets were examined for the presence of reticular material (subvital Giemsa stain) and CD71 expression (Figure 2D-F). As expected, the majority of infected reticulocytes were CD71+ immediately postinvasion (Figure 2F), whereas most uninfected reticulocytes were CD71−. By 3 hours postinvasion, the P vivax–invaded reticulocytes were mainly CD71−, as were the uninfected reticulocytes, but in stark contrast to the uninfected cells, the P vivax–infected cells became almost completely devoid of reticular matter by 3 hours postinvasion (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 1A).

P vivax infection induces a rapid remodeling of the cell surface and the cytoplasmic compartments of immature reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry of P vivax field isolates stained with Hoechst and for CD71 using a gating strategy to identity CD71+ (pink) and CD71− (purple) P vivax–infected cells. (B) Proportion of CD71− (pink bars) and CD71+ (purple bars) P vivax (Pv)-infected cells from 13 clinical samples. The mean percentage of uninfected CD71+ cells is 1.29% ± 1.31% SD. (C) Gating strategy for CD71+ and CD71−P vivax rings flow cytometry sorting; the lower Hoechst signal is associated with ring-stage parasites. The insert on the right shows the SEM scans of the 2 populations (scale bars represent 1 μm) and the blue box indicates the area shown at higher magnification (scale bars represent 100 nm). (D) The exclusion reticular material (subvitally stained with Giemsa) in uninfected and P vivax–infected CD71+ reticulocytes over a period of 40 hours. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (E) Rapid disappearance of CD71 in an ex vivo P vivax–invaded reticulocyte. These freshly invaded CD71+ reticulocytes with P vivax rings were counterstained with Alexa 546 and Hoechst to stain parasite DNA and were observed under a fluorescent microscope during the first 3 hours postinvasion. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (F) Frequency of CD71+ (pink) and CD71− (purple) uninfected or P vivax–infected reticulocytes at invasion 0 and 3 hours after reinvasion.

P vivax infection induces a rapid remodeling of the cell surface and the cytoplasmic compartments of immature reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry of P vivax field isolates stained with Hoechst and for CD71 using a gating strategy to identity CD71+ (pink) and CD71− (purple) P vivax–infected cells. (B) Proportion of CD71− (pink bars) and CD71+ (purple bars) P vivax (Pv)-infected cells from 13 clinical samples. The mean percentage of uninfected CD71+ cells is 1.29% ± 1.31% SD. (C) Gating strategy for CD71+ and CD71−P vivax rings flow cytometry sorting; the lower Hoechst signal is associated with ring-stage parasites. The insert on the right shows the SEM scans of the 2 populations (scale bars represent 1 μm) and the blue box indicates the area shown at higher magnification (scale bars represent 100 nm). (D) The exclusion reticular material (subvitally stained with Giemsa) in uninfected and P vivax–infected CD71+ reticulocytes over a period of 40 hours. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (E) Rapid disappearance of CD71 in an ex vivo P vivax–invaded reticulocyte. These freshly invaded CD71+ reticulocytes with P vivax rings were counterstained with Alexa 546 and Hoechst to stain parasite DNA and were observed under a fluorescent microscope during the first 3 hours postinvasion. Scale bar represents 1 μm. (F) Frequency of CD71+ (pink) and CD71− (purple) uninfected or P vivax–infected reticulocytes at invasion 0 and 3 hours after reinvasion.

Under normal circumstances, CD71 is lost from the maturing reticulocyte by exocytosis (involving exosomes).9,29 However, the excrescences (size >200 nm) observed on the infected reticulocytes (Figure 2C) were more akin to microvesicles than exosomes.30 This is consistent with the rapidity of microvesicle formation observed in ionomycin-treated CD71+ reticulocytes (supplemental Figure 1B) and that reported for ionomycin-treated RBCs.31 Elucidating the exact nature of the structures observed at the surface of early CD71+P vivax rings, however, remains a matter for future studies.

Changes in the membrane nanostructure of P vivax–infected reticulocytes

In addition to the microvesicle-like structures at the surface of newly invaded CD71+ reticulocytes, the SEM scans also clearly revealed the presence of “holes” of ∼100 nm in diameter (Figure 2B). However, SEM alone could not help distinguish whether these were the openings to clathrin pits (a complex of clathrin proteins and CD71 receptors; vital for the endocytosis of iron-loaded transferrin into the developing RBC) or whether they were the openings to the parasite-derived “caveolae vesicle complexes” (CVCs).32 Thus, we examined CD71+ reticulocytes (3 isolates, 60 cells), newly invaded reticulocytes (3 isolates, 60 cells), and ex vivo matured P vivax IRBCs (10 isolates, 485 cells) by AFM and transmission electron microscopy.

Examination of the reticulocytes’ clathrin pits (n = 124) and the caveolae on mature P vivax IRBCs (n = 343) clearly shows that they differ morphologically and in size. Clathrin pits are cup-shaped depressions with openings significantly larger than those of the amphora-shaped caveolae (mean diameters of 109.92 nm and 88.97 nm, respectively) of P vivax IRBCs (Figure 3A-B). It was also noted that the apertures of clathrin pits were generally symmetrical, whereas those of the caveolae were asymmetrical (Figure 3A). Using these morphological characteristics, it was possible to examine AFM smears from staged P vivax IRBCs and describe the evolution of these 2 nanostructures as the parasites mature (Figure 3A). We are aware that the rigid rule we adopted to define the 2 structures (caveolae with diameters ≤90 nm; clathrin pits with diameters >90 nm, associated to the radial symmetry of the opening) is subject to error, resulting in some misidentification. Nonetheless, the general trends are quite clear: the density of clathrin pits is greatly reduced following the invasion event, whereas the highest density of the caveolae is rapidly reached (within 6 to 8 hours) postinvasion (ring stage) (Figure 3C-D).

Comparative phenotypic characterization of clathrin pits and caveolae in uninfected reticulocytes and P vivax IRBCs. (A) Representative AFM scans that illustrate the presence and density of clathrin pits on uninfected reticulocytes and of caveolae on P vivax IRBCs; the bottom inserts show the shape of these 2 nanostructures as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. (B) The range of the diameters of the 2 nanostructures observed on uninfected reticulocytes and on P vivax IRBCs and (C) changes in the distribution of caveolae and clathrin pits with the ex vivo maturation of the P vivax IRBCs (both observations derived from the same 13 independent isolates [staged ex vivo maturation], with total of 485 IRBCs examined). The P vivax isolates we received for this staged ex vivo maturation were >6 hours old (n = 10), thus we needed to conduct 3 invasion assays (n = 3) to get AFM data on the missing 0 to 6 hour postinvasion window (tiny ring stage). (D) Representative AFM scans of P vivax IRBCs at various stages of development and the directly corresponding Giemsa-stained picture. This set of scans was taken from staged ex vivo invasion and maturation assay. Bar represents 10 μm.

Comparative phenotypic characterization of clathrin pits and caveolae in uninfected reticulocytes and P vivax IRBCs. (A) Representative AFM scans that illustrate the presence and density of clathrin pits on uninfected reticulocytes and of caveolae on P vivax IRBCs; the bottom inserts show the shape of these 2 nanostructures as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. (B) The range of the diameters of the 2 nanostructures observed on uninfected reticulocytes and on P vivax IRBCs and (C) changes in the distribution of caveolae and clathrin pits with the ex vivo maturation of the P vivax IRBCs (both observations derived from the same 13 independent isolates [staged ex vivo maturation], with total of 485 IRBCs examined). The P vivax isolates we received for this staged ex vivo maturation were >6 hours old (n = 10), thus we needed to conduct 3 invasion assays (n = 3) to get AFM data on the missing 0 to 6 hour postinvasion window (tiny ring stage). (D) Representative AFM scans of P vivax IRBCs at various stages of development and the directly corresponding Giemsa-stained picture. This set of scans was taken from staged ex vivo invasion and maturation assay. Bar represents 10 μm.

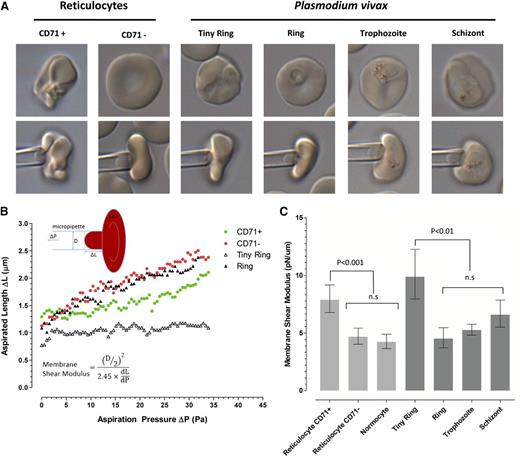

Biomechanical properties of immature reticulocytes infected with P vivax

The deformability of staged P vivax IRBCs was investigated in 2 previous studies,33,34 but in neither was the membrane component of an individual infected red cell specifically examined and, in both, normocytes rather than reticulocytes were used as controls. We opted to use the gold standard micropipette aspiration technique to measure biomechanical changes to the infected reticulocyte (Figure 4A); to our knowledge, the first time this has been applied to P vivax IRBCs.

Evolution of cell deformability during the maturation of P vivax. (A) Representative micropipette aspiration images of CD71+ and CD71− reticulocytes and of P vivax IRBCs at the different maturation stages (based on the size of the parasitophorous vacuole and arrangement of hemozoin). (B) Key examples of single-cell measurements of cell length aspirated with different pressure intensities. Also provided is a diagram (upper left corner) and the equation (lower left corner) to show how the shear flow modulus for each cell was calculated. ΔL, aspirated length; ΔP, aspirating pressure; D, micropipette inner diameter; dL/dP, slope of the linear region of the aspiration graph as shown in this figure. (C) The median shear flow modulus (± interquartile range) of each population. Note that the uninfected CD71+ reticulocytes and tiny ring forms have the highest shear modulus (ie, the most rigid cells), which was significantly higher than any of the other normocytes and other infected red cells. n.s., not significant.

Evolution of cell deformability during the maturation of P vivax. (A) Representative micropipette aspiration images of CD71+ and CD71− reticulocytes and of P vivax IRBCs at the different maturation stages (based on the size of the parasitophorous vacuole and arrangement of hemozoin). (B) Key examples of single-cell measurements of cell length aspirated with different pressure intensities. Also provided is a diagram (upper left corner) and the equation (lower left corner) to show how the shear flow modulus for each cell was calculated. ΔL, aspirated length; ΔP, aspirating pressure; D, micropipette inner diameter; dL/dP, slope of the linear region of the aspiration graph as shown in this figure. (C) The median shear flow modulus (± interquartile range) of each population. Note that the uninfected CD71+ reticulocytes and tiny ring forms have the highest shear modulus (ie, the most rigid cells), which was significantly higher than any of the other normocytes and other infected red cells. n.s., not significant.

The normal maturation from CD71+ immature reticulocytes to CD71− reticulocytes and normocytes is characterized by significant reductions in shear modulus/rigidity (ie, an increase in membrane deformability). The rigidity of freshly invaded CD71+ reticulocytes (tiny rings >3 hours postinvasion) was unchanged, if not slightly increased, compared with uninfected control cells, but within 6 to 8 hours postinvasion (ring stage), the shear modulus was dramatically reduced to reach levels identical to those measured for the highly deformable uninfected normocytes (Figure 4B-C). Although the trophozoite stages retained deformability, there was a slight increase in the shear modulus at the schizont stage (Figure 4C).

Discussion

The significant contribution of P vivax infections to the global burden of malaria is now once again appreciated. The divergent biological and clinical characteristics of the P vivax and P falciparum infections dictate investigations specific to each species to elucidate the mechanisms that underlie their distinct pathobiology. One of the central factors that shape the virulence of the malaria blood infection is the rate of parasite multiplication. This in turn rests on the efficiency of RBC invasion and on the fraction of IRBCs that survive to produce fresh merozoites. In this article, we present observations on P vivax that provide novel insights into both of these phenomena. The 2 salient features we uncovered are the distinct preference of P vivax for immature reticulocytes and the rapidity with which the invaded RBC is remodeled.

Narrow reticulocyte tropism and the implication of bone marrow

The discovery that P vivax merozoites have a distinct preference to invade CD71+ reticulocytes, whereas CD71− reticulocytes are relatively refractory to invasion, was unexpected. Indeed, the CD71− maturing reticulocytes are predominantly found in the peripheral circulation, whereas the CD71+ immature reticulocytes are largely confined to the bone marrow.5,9,12-15,28,35 This raises the possibility that the bulk of P vivax invasion occurs in the bone marrow and not in the blood.

The first observations of malaria parasites in bone marrow were made by Marchiafava and colleagues in the 1890s36 and confirmed in the early 1920s by Seyfarth (the inventor of sternal punctures for pathogen diagnosis).37 In one of the first published studies where this was applied to a series of malaria patients, the authors concluded that “Malarial parasites can always be found in the bone marrow in tertian, quartan, and subtertian malaria, when found in the blood. They may, however, be discoverable in the marrow when absent from the blood”.38 Indeed, in subsequent studies, bone marrow parasitemias were on average double those of the peripheral blood,39 and many patients with negative blood smears were only found to be infected by P vivax by sternal puncture.40-43 These observations suggest that the bone marrow is a site of P vivax accumulation, but they do not shed any light on whether these parasites were collecting in the primary extravascular sinusoids, in the lumen of the sinusoidal capillaries, or in both. Recent histopathological observations_clearly demonstrated the presence and enrichment of P falciparum gametocytes in the extravascular compartment of the bone marrow.44,45 Similar investigations of postmortem samples from vivax malaria cases would be of great value.

Under normal conditions, the sinusoidal lining (endothelial cells) of the bone marrow is continuous, although temporary formation of intracellular migratory pores occurs to allow the transit of Heilmeyer stage III reticulocytes from the primary hematopoietic sinus (red bone marrow) by diapedesis.46 Thus, only those stage III reticulocytes that have migrated out of the red bone marrow, or indeed that are in the process of doing so, would be available for P vivax invasion (Figure 5), an event that would be confined to the marrow capillaries and that is plausible with the accumulation of P vivax IRBCs in the bone marrow. In an alternative scenario, one could speculate that the invasion events take place principally extravascularly, in the red bone marrow. Such a phenomenon implies that those P vivax merozoites (or even maturing P vivax IRBCs) could migrate from the sinusoidal capillary lumen to the primary hematopoietic sinus (Figure 5). Furthermore, this would also entail a stage III reticulocyte freshly invading into the red bone marrow would be able to traverse the sinusoidal lining to reach the blood circulation. It would seem improbable that the only permanent openings in the sinusoidal lining, the intracellular sinusoidal channels of restricted diameter (<100 nm) that only allow plasma transfer, would serve as a conduit for the passage of merozoites, RBCs, or P vivax IRBCs.46,47 However, it is possible that pathological changes inherent to the P vivax infection, such as anemia or localized inflammatory reactions, could cause a disruption of the sinusoidal lining that would permit cellular transit.48 From a biomechanical point of view, the high deformability of the P vivax IRBC would not be an impediment for crossing the endothelial barrier.34 Finally, extravascular invasion might account for the finding of P vivax in bone marrow aspirates in patients with undetectable peripheral blood parasitemia. Irrespective of which scenario reflects best the actual events in P vivax infections, it seems clear that the bone marrow plays an important role in the pathobiology of P vivax malaria, and future studies should consider that the accumulation of P vivax in the bone marrow might contribute to the total parasite biomass.

Hypothetical interactions between P vivax (P.v.) and bone marrow reticulocytes. The reticulocytes (blue) display a gradient of surface CD71 (from high CD71 expression on the erythroblasts [0] to the CD71− stage IV reticulocytes). Stage 0 erythroblasts and stages I/II reticulocytes are present in a steady state in the primary hematopoietic sinus of the red bone marrow. Stage III reticulocytes egress by diapedesis to the sinusoidal capillary lumen and then join the peripheral blood. It is presently considered that this is where the reticulocytes are infected by P vivax, after which rapid host cell remodeling is induced and is associated with microvesicle formation and an accelerated loss of various surface markers, including CD71 and reticular matter. Our in vitro observations indicated that the stage I/II reticulocytes (and possibly the erythroblasts) are the preferred targets for the merozoite. This suggests that P vivax merozoites, or indeed P vivax IRBCs, might be able to enter the red bone marrow compartment and invade their preferred host cells there.

Hypothetical interactions between P vivax (P.v.) and bone marrow reticulocytes. The reticulocytes (blue) display a gradient of surface CD71 (from high CD71 expression on the erythroblasts [0] to the CD71− stage IV reticulocytes). Stage 0 erythroblasts and stages I/II reticulocytes are present in a steady state in the primary hematopoietic sinus of the red bone marrow. Stage III reticulocytes egress by diapedesis to the sinusoidal capillary lumen and then join the peripheral blood. It is presently considered that this is where the reticulocytes are infected by P vivax, after which rapid host cell remodeling is induced and is associated with microvesicle formation and an accelerated loss of various surface markers, including CD71 and reticular matter. Our in vitro observations indicated that the stage I/II reticulocytes (and possibly the erythroblasts) are the preferred targets for the merozoite. This suggests that P vivax merozoites, or indeed P vivax IRBCs, might be able to enter the red bone marrow compartment and invade their preferred host cells there.

Rapid remodeling and accelerated aging of P vivax–infected immature reticulocytes

The transformation of rigid CD71+ immature reticulocytes to deformable CD71− within 6 hours after invasion by P vivax infection is astonishing. How P vivax causes the accelerated loss of the clathrin pits containing CD71 is not presently known, but the formation of microvesicles observed in newly invaded reticulocytes may provide some indications. In this context, the recent demonstration that extracellular vesicles generated by P falciparum IRBCs have a role in the cellular communication49,50 is of interest, as are the observations of circulating microparticles in clinical isolates from malaria patients.51,52 By 6 to 8 hours postinvasion, the clathrin pits and microvesicles are no longer present on the surface of the IRBC and are replaced by caveolae of parasitic origin. These caveolae, first described in the 1970s in P vivax IRBCs, are usually associated with numerous vesicles, and the combined structure are referred to as the CVCs.32,53-55 It is thought that CVCs are involved in the endocytosis of macromolecules vital for the development of P vivax,32 and the rapid appearance of caveolae at the ring stage and their maintenance to the end of the asexual cycle would seem to support this assertion. Although Barnwell et al and Akinyi et al53,56 have characterized parasitic proteins associated with the vesicle complexes, little is known about the proteins associated with the actual caveolae opening. Aikawa suggests that, unlike the positively charged vesicles, the negatively charged caveolae opening are largely host-derived.32 However, we consider it unlikely that host or parasitic caveolins are involved in the formation of these “caveolae,” because we could not detect caveolein-1 in reticulocytes or in the P vivax IRBCs (supplemental Figure 2A-B). Although this contradicts the findings of Bracho et al,57 we could not find genes encoding caveolins or flotillins in the P vivax genome,58 nor records of caveolin in human red cells.

Of all the changes occurring during the early development of P vivax in immature reticulocytes, the most notable is the rapid switch from a ridged immature reticulocyte to a deformable infected RBC. The increased deformability of P vivax IRBCs is generally thought to be an adaption that would enable the parasitized red cell to escape splenic clearance.33,34 We would like to suggest that increased deformability might additionally augment the delivery of mature parasites into the compartments of the bone marrow and the egress of infected reticulocytes into the peripheral blood system. We also noted that P vivax gametocytes were equally highly deformable (results not shown).

Conclusion

The observed marked preference of P vivax to invade immature reticulocytes provides an appropriate baseline to seek the identity of the molecules involved in invasion specificity and to elucidate the nature of the mechanisms that lead to the biomechanical, nanostructural, and biomolecular characteristics of the invaded RBC. It also cautions researchers to take into account that the CD71+ immature reticulocytes targeted by P vivax are significantly different from the CD71− reticulocytes and normocytes, making it important to select appropriate controls for any experiments. From a clinical point of view, the narrow tropism of P vivax for immature reticulocytes normally only found in the bone marrow places events at this compartment of the body at the center of investigations on the pathological processes in vivax malaria. In addition to the pathological consequences of the accumulation of P vivax IRBCs in bone marrow, the potential existence of cryptic P vivax populations away from the peripheral circulation has far-reaching implications for the treatment of vivax malaria and for the prospects of its elimination from current endemic areas.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is an Inside Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN) flow cytometry core headed by Dr Anis Larbi, particularly Ivy Low, Seri Mustafah, and Nurhidaya Shadan; the Electron Microscopy Unit, National University of Singapore, particularly Tan Suat Hoon and Lu Thong Beng; the staff and patients attending the Mae Sot Malaria Clinic and also clinics associated with the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU), Tak Province, Thailand; and Professors Yves Colin Aronovicz and Olivier S. Bertrand (INSERM/University Paris Diderot) for the generous gift of the anti-DARC antibodies vital to this study.

This work was funded by the Singapore National Medical Research Council (NMRC/CBRG/0047/2013), the SIgN, the Horizontal Programme on Infectious Diseases, a Young Investigator Grant (BMRC YIG grant no. 13/1/16/YA/009) (B.M.) under the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR, Singapore), and a Singapore International Graduate Award (J.S.C.). SMRU is supported by The Wellcome Trust of Great Britain as part of the Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Programme of Wellcome Trust-Mahidol University. B.M. has a joint appointment with the National University of Singapore and A*STAR; J.S.C. is hosted by the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Authorship

Contribution: B.R., B.M., A.L., R.Z., R.S., C.C., J.S.C., and E.G.L.K. carried out laboratory work and collected and analyzed the data; C.S.C., S.P., and F.N. provided clinical management of patients, ethical clearance, and collection and processing of the blood samples; B.M., B.R., K.S.W.T., M.L.N., F.G., L.G.N., C.T.L., G.S., and L.R. participated in data interpretation and helped to draft the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of interest-disclosure: The authors declare no competing interests.

Correspondence: Laurent Rénia, Singapore Immunology Network, A*STAR, 8A Biomedical Grove, Singapore 138648, Singapore; e-mail: renia_laurent@immunol.a-star.edu.sg; and Bruce Russell, Department of Microbiology, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, 5 Science Dr, Blk MD4, Level 3, Singapore 117597, Singapore; e-mail: micbmr@nus.edu.sg.

![Figure 1. Reticulocyte tropism of P vivax is restricted to CD71+ reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD71 and TO staining used to define the different erythrocyte subsets: TO+/CD71+ for the immature reticulocytes (green box), TOlow/CD71− for the mature reticulocytes (red box), and TO−/CD71− for the normocytes (black box). The insets on the right show the NMB-stained reticulocytes sampled from these gates by flow cytometry sorting. (B) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for normocytes (TO−/CD71−) (mean 2.17 ± 1.23 standard deviation [SD] vs 9.47 ± 4.81 SD), for the 3 reticulocyte subsets harvested by cell sorting. Bar represents 8 μm. (C) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the reticulocyte sampling based on the CD71 expression (CD71−, CD71low, CD71medium, CD71high). The top insets show each population stained by NMB. Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. (D) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for the CD71− population and for the 3 younger reticulocyte populations (mean CD71low: 5.09 ± 1.75 SD; CD71medium: 6.53 ± 2.41 SD; CD71high: 7.94 ± 3.14 SD; n = 3). Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. Bar represents 8 μm. (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing Hoechst and ethidium levels observed at the start (0 hours) and after 24 hours of the reinvasion assay with CD71− erythrocytes, and CD71+ reticulocytes treated or not with anti-Duffy antibodies. For the 0-hour data, the black thick-lined squares show the percentage of schizonts; the black thin-lined squares show the percentage of rings before invasion. For the 24 hours of data, the black thin-lined squares at 24 hours show the percentage of unburst schizonts; the orange thick-lined squares show the percentage of rings after invasion. (F) The percentage of rings after reinvasion (n = 5). The value observed with CD71+ reticulocytes incubated with anti-Duffy antibodies was taken as the threshold of reinvasion (0.74%). hr, hour. *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f1.jpeg?Expires=1765899689&Signature=G3tPwqrirN9mpt1PXsIqnj1upirHmbQF9Ebwp~SZkEEbrDU6N2vK3MPJGHZzXs28Sf8mtsNjFO~ixDIvFBG5JvA0LG1kW9VukNmTImXddxr-wepxPRUzY1bktzlvF9bYf1rgjGhs5GAd2BATngIfK5Esb3G1fjeO5dobNx7hDG5hij4Yv36Fzest3W3496OWEP7DO68FNJ8ujdgT2dlv8n04XjQvBrEqCRamEzBY0U2EAHlLJitK8bL0dtTKFzG5ftxnvlEAG0sYcWC-Uv4K9fKZAgvTLwHEVm8TxM7DO4MH-i5XYwTYrc-FmMCYxJ60rzdqnePUHG6Op3RotdS1Qw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Comparative phenotypic characterization of clathrin pits and caveolae in uninfected reticulocytes and P vivax IRBCs. (A) Representative AFM scans that illustrate the presence and density of clathrin pits on uninfected reticulocytes and of caveolae on P vivax IRBCs; the bottom inserts show the shape of these 2 nanostructures as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. (B) The range of the diameters of the 2 nanostructures observed on uninfected reticulocytes and on P vivax IRBCs and (C) changes in the distribution of caveolae and clathrin pits with the ex vivo maturation of the P vivax IRBCs (both observations derived from the same 13 independent isolates [staged ex vivo maturation], with total of 485 IRBCs examined). The P vivax isolates we received for this staged ex vivo maturation were >6 hours old (n = 10), thus we needed to conduct 3 invasion assays (n = 3) to get AFM data on the missing 0 to 6 hour postinvasion window (tiny ring stage). (D) Representative AFM scans of P vivax IRBCs at various stages of development and the directly corresponding Giemsa-stained picture. This set of scans was taken from staged ex vivo invasion and maturation assay. Bar represents 10 μm.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f3.jpeg?Expires=1765899689&Signature=wrcOM63YJe-hfHW7EYj3e7XxVGJszlx5Irj-sZNa2OkFNFoMcm1towSRz4WYpIVOtOUm9MlNfGCR9CZ~hKGMvi5jiEiOw5WbMq2hBKV1T4-FNhmLijhv5APXXvj3a7NpUzwp8HThWzfeg8yPqCCkId6oofqj~n3nvYpbVFYYaY-sephSbGcWWks1Pw1eWoXVdOkhItjiYL8TyUolVfzL6NFsZ~mz5Ca2UVdsB6a4Z0-AhjLOxhvLIzw3DwA3eq71lqGHPemceIuZiI1EpZyFyDO5vm8zXjasLvNbDMhVLMhfM4e6bmineQZPIbi4zRhl4xbVylGgxALsX9xLhemt6Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Hypothetical interactions between P vivax (P.v.) and bone marrow reticulocytes. The reticulocytes (blue) display a gradient of surface CD71 (from high CD71 expression on the erythroblasts [0] to the CD71− stage IV reticulocytes). Stage 0 erythroblasts and stages I/II reticulocytes are present in a steady state in the primary hematopoietic sinus of the red bone marrow. Stage III reticulocytes egress by diapedesis to the sinusoidal capillary lumen and then join the peripheral blood. It is presently considered that this is where the reticulocytes are infected by P vivax, after which rapid host cell remodeling is induced and is associated with microvesicle formation and an accelerated loss of various surface markers, including CD71 and reticular matter. Our in vitro observations indicated that the stage I/II reticulocytes (and possibly the erythroblasts) are the preferred targets for the merozoite. This suggests that P vivax merozoites, or indeed P vivax IRBCs, might be able to enter the red bone marrow compartment and invade their preferred host cells there.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f5.jpeg?Expires=1765899689&Signature=QklpR9SQ5HIWGs8nsLfJ10Lq2KvTUIMUVFZDDZODfoy1ysPMh5wwk10bGLRkbGYjKZo8~Om2I4yMwgFr70ubNjybMM~n~QN3A-~vNuYybkQblciV-1-AI1rsRxGjzLLQIbElf2Sg8mewsGpVABZYBRfaTToMRpEMLkBHZkIcHY~8yP5XBzmrTWLQ-vPV5jrd1dsxneIN8FygY0abKT1vCovI0NYcYFayID9VqtAtuhrooIt0TAmGi-3-tkWC1EiJ3P9fof0KMNC8Ut0sJj8L-WvQbxr2yZKuOeVhYvBJsdd3~7j-RImuUdYrRKktGsKUgKxSFFj0k6oZWR5XvN3GIw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Reticulocyte tropism of P vivax is restricted to CD71+ reticulocytes. (A) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the CD71 and TO staining used to define the different erythrocyte subsets: TO+/CD71+ for the immature reticulocytes (green box), TOlow/CD71− for the mature reticulocytes (red box), and TO−/CD71− for the normocytes (black box). The insets on the right show the NMB-stained reticulocytes sampled from these gates by flow cytometry sorting. (B) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for normocytes (TO−/CD71−) (mean 2.17 ± 1.23 standard deviation [SD] vs 9.47 ± 4.81 SD), for the 3 reticulocyte subsets harvested by cell sorting. Bar represents 8 μm. (C) Flow cytometry dot plot showing the reticulocyte sampling based on the CD71 expression (CD71−, CD71low, CD71medium, CD71high). The top insets show each population stained by NMB. Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. (D) Histogram showing the fold increase reinvasion, normalized to that measured for the CD71− population and for the 3 younger reticulocyte populations (mean CD71low: 5.09 ± 1.75 SD; CD71medium: 6.53 ± 2.41 SD; CD71high: 7.94 ± 3.14 SD; n = 3). Note the red arrows in the right insets showing the newly reinvaded erythrocytes stained with Hoechst. Bar represents 8 μm. (E) Representative flow cytometry dot plot showing Hoechst and ethidium levels observed at the start (0 hours) and after 24 hours of the reinvasion assay with CD71− erythrocytes, and CD71+ reticulocytes treated or not with anti-Duffy antibodies. For the 0-hour data, the black thick-lined squares show the percentage of schizonts; the black thin-lined squares show the percentage of rings before invasion. For the 24 hours of data, the black thin-lined squares at 24 hours show the percentage of unburst schizonts; the orange thick-lined squares show the percentage of rings after invasion. (F) The percentage of rings after reinvasion (n = 5). The value observed with CD71+ reticulocytes incubated with anti-Duffy antibodies was taken as the threshold of reinvasion (0.74%). hr, hour. *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f1.jpeg?Expires=1765899690&Signature=coHzEU2Y7xYr762MA36-17wCGHfX--FOlrgTwbXseXhj75l8ttUWcSXe2QaeX4IgmmFjocZv4~33Kpx1AB-GiA8Hcl8TnO0gWppKlIhSBvtwofcOYnnPeR8aIcvbCoEmBXt8lXF0wPRz8jA-krjNhpEoJyKQDjODT0zHdmp4HOgZ9TYQGRvc-CqTg9d9ZJ4LHd151VQwfsSd5NPIAAUac7TtPGrG5NFbQNWrUrIvODFyBnaEg~mWunTwRjgazNhbgUSFRA4QLjJcb6Jc789Te6a-80EYYa5Y~4yNd0FZXk0dUJtfSRJGCRVizM-ynoCYh8mR8BDOrsynF~7k0KoIlQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Comparative phenotypic characterization of clathrin pits and caveolae in uninfected reticulocytes and P vivax IRBCs. (A) Representative AFM scans that illustrate the presence and density of clathrin pits on uninfected reticulocytes and of caveolae on P vivax IRBCs; the bottom inserts show the shape of these 2 nanostructures as revealed by transmission electron microscopy. (B) The range of the diameters of the 2 nanostructures observed on uninfected reticulocytes and on P vivax IRBCs and (C) changes in the distribution of caveolae and clathrin pits with the ex vivo maturation of the P vivax IRBCs (both observations derived from the same 13 independent isolates [staged ex vivo maturation], with total of 485 IRBCs examined). The P vivax isolates we received for this staged ex vivo maturation were >6 hours old (n = 10), thus we needed to conduct 3 invasion assays (n = 3) to get AFM data on the missing 0 to 6 hour postinvasion window (tiny ring stage). (D) Representative AFM scans of P vivax IRBCs at various stages of development and the directly corresponding Giemsa-stained picture. This set of scans was taken from staged ex vivo invasion and maturation assay. Bar represents 10 μm.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f3.jpeg?Expires=1765899690&Signature=xM5LdMQbhZqfynUDvScfoKAYKLk04EbFEXvHzWsIRd9enqP6H~C8OKLX1GUB9DICJFvujjO1QG2d0hokUcde-0B9osFY9ePo6S56NkxE9wVKMh8fUN8imPndUbrSyv0Tfjhz04O-eyk~~vjfLJWe5l9I1Jap-wjW4AD2PDRUNHwWi4iV3sObykmEHTzhIenKqPWe-aKsd~RGBFiYxLLYTple~po3sWWzQny8N1fxU8y0TAfqKk48Jg01SQOxJA2jAEojcVHwRbJyVNXCTXML9iUnSkm1nd07DsMW9HNAjxEcf5xP-VZib-q7GQodqo7NjHotpfbP6Aq90mTSDRxcfw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Hypothetical interactions between P vivax (P.v.) and bone marrow reticulocytes. The reticulocytes (blue) display a gradient of surface CD71 (from high CD71 expression on the erythroblasts [0] to the CD71− stage IV reticulocytes). Stage 0 erythroblasts and stages I/II reticulocytes are present in a steady state in the primary hematopoietic sinus of the red bone marrow. Stage III reticulocytes egress by diapedesis to the sinusoidal capillary lumen and then join the peripheral blood. It is presently considered that this is where the reticulocytes are infected by P vivax, after which rapid host cell remodeling is induced and is associated with microvesicle formation and an accelerated loss of various surface markers, including CD71 and reticular matter. Our in vitro observations indicated that the stage I/II reticulocytes (and possibly the erythroblasts) are the preferred targets for the merozoite. This suggests that P vivax merozoites, or indeed P vivax IRBCs, might be able to enter the red bone marrow compartment and invade their preferred host cells there.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/125/8/10.1182_blood-2014-08-596015/5/m_1314f5.jpeg?Expires=1765899690&Signature=zkQc8yWExOWpHJLXLr7RgVPXQts1POJ1-w5YpbkLKxQefaetroG0lK0VysOWE~x~WaSfSnU37olsXHMazdo2AyTuI35cjJa12~2XuVVJeHMSlYx5UxURy~wSws7EXmZxTsNFa8mAwIwqeFzuadCyszUHsOMHGbuywgihOf5Uu0GRgRtEeugJo7Kf~5gXoe4b2T1s1mGW76OjQNmmzJ1stIi9XLneeuTv~yal7cL-sLaVn56GIMU-a2PMgP9CXYsWCmX4cPBGEUOeTf7ZHLIaPsqkbm9RGgu6w0Fi~ZsVr5CE0ASI1gjpKjXv6gJLsuLUMRM-AlW3uEpxYTkSOpw2nA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)