Key Points

Nbs1 is a component of the MRE11 complex, which is a sensor of DNA double-strand breaks and plays a crucial role in the DNA damage response.

In mice with a hypomorphic allele of Nbs1, macrophages exhibit increased senescence and abnormal proliferation and inflammatory responses.

Abstract

Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1) is a component of the MRE11 complex, which is a sensor of DNA double-strand breaks and plays a crucial role in the DNA damage response. Because activated macrophages produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can cause DNA lesions, we examined the role of NBS1 in macrophage functional activity. Proliferative and proinflammatory (interferon gamma [IFN-γ] and lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) stimuli led to increased NBS1 levels in macrophages. In mice expressing a hypomorphic allele of Nbs1, Nbs1∆B/∆B, macrophage activation–induced ROS caused increased levels of DNA damage that were associated with defects in proliferation, delayed differentiation, and increased senescence. Furthermore, upon stimulation, Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages exhibited increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines. In the in vivo 2,4-dinitrofluorobenezene model of inflammation, Nbs1∆B/∆B animals showed increased weight and ear thickness. By using the sterile inflammation by zymosan injection, we found that macrophage proliferation was drastically decreased in the peritoneal cavity of Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. Our findings show that NBS1 is crucial for macrophage function during normal aging. These results have implications for understanding the immune defects observed in patients with NBS and related disorders.

Introduction

Endogenous sources of DNA damage, such as DNA replication or reactive oxygen species (ROS), can cause a diverse spectrum of DNA lesions.1 Among these, DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are considered one of the most cytotoxic and can promote oncogenic translocations if not properly metabolized. DSBs are repaired by 2 major pathways: nonhomologous end-joining and homologous recombination.2,3 The MRE11 complex, composed of meiotic recombination 11 homolog (MRE11), Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 (NBS1), and RAD50, is a DSB sensor that regulates the DNA damage response (DDR) and repair of DSBs.4 Break detection by the MRE11 complex activates the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase that promotes a robust DDR that includes the activation of checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2) and the tumor suppressor p53.5

NBS1 has no identifiable enzymatic activities and appears to function primarily as an adaptor protein required for MRE11 complex nuclear localization. NBS1 has a forkhead-associated domain and two BRCA1 C-terminal (BRCT) domains involved in phospho-dependent protein interactions in its N terminus and an MRE11 and PI3K-related protein kinase (PIKK) binding domain in its C terminus.6,7 The latter domain interacts with ATM and is required for an efficient apoptotic response in the immune system.7,8

Mutations in any MRE11 complex members or ATM underlies rare genetic instability syndromes with overlapping pathologies that affect the central nervous system, germline, and immune system.4,7 NBS1 mutations cause Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS),7,9,10 characterized by microcephaly, growth and mental retardation, immunodeficiency, and predisposition to cancer.11 This syndrome highlights the importance of the DDR in the development and function of the central nervous and immune systems.

Immunological defects in NBS patients are poorly understood. T and B cells have been the major focus, because variable (diverse) joining segments and class switch recombination result in the production and repair of DSBs to facilitate immunoglobulin development.12,13

Macrophages play a critical role during proinflammatory (destructive) and anti-inflammatory (repairing) phases of inflammation.14-16 Recently, it has been found that when an inflammation is produced, Ly6Chigh monocytes are released by the bone marrow (BM) to fight pathogenic intruders at inflammatory loci throughout the body.17 Macrophages may experience DSBs during the proliferation and also during activation, because they are the major producer of NO and ROS that can induce these and other lesions.18 This suggests that the proper control of DNA damage repair and proliferation is likely to be important in macrophages19 and could be affected by mutations in the MRE11 complex.

To address this possibility, we examined the role of NBS1 in macrophages using mice that express a hypomorphic allele of Nbs1, Nbs1∆B/∆B.20 Nbs1∆B/∆B mice express a truncated allele that lacks the N-terminal forkhead-associated and BRCT domains that are crucial for cell cycle checkpoints, DNA damage sensitivity, and efficient ATM signaling.8,20 Our results demonstrate that reduced NBS1 function promotes macrophage senescence, reflected by slow macrophage differentiation, reduced proliferation, and an impaired inflammatory response and suggest that its role in macrophages may contribute to the immunodeficiency observed in patients with NBS.

Materials and methods

Mice

Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were a kind gift from Dr John H. Petrini.20 All mice were maintained in a specific-pathogen-free facility in the Parc Cientific de Barcelona. Animal use was approved by the Animal Research Committee of the Government of Catalonia, no. 2523.

Reagents

Murine recombinant interferon gamma (IFN-γ), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), granulocyte macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), and interleukin-4 (IL-4) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and CpG-B was purchased from InvivoGen (San Diego, CA). All chemicals used were of the highest purity grade available from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), unless stated otherwise.

BM-derived macrophage culture

BM-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were generated as described.21 A homogeneous population of adherent macrophages was obtained after 7 days of culture (>99% CD11b and F4/80).

RNA extraction, qPCR, and PCR

Total RNA was extracted, purified, and DNase treated with PureLink RNA Mini Kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Ambion, Life Technologies). Complementary DNA synthesis and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were performed by using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) as described.22 Data were normalized using Hprt1 and/or l14 as housekeeping genes. Primer sequences are presented in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site. For PCR analysis of Nbs1 fragments, the total RNA extracted was used as a template for complementary DNA preparation, and the conditions of the PCR were 5 minutes at 95°C, 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 58°C, and 1 minute at 72°C (for 30 cycles), plus a 10-minute extension at 72°C.

Western blot protein analysis

Western blotting was performed as described23 by using antibodies against NBS1 (Novus Biologicals), ATR (Cell Signaling), CHK2 (EMD Millipore), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and LC3 (Sigma-Aldrich).

Telomere length

DNA was extracted by using the DNeEasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen), and DNA was amplified by qPCR with telomere-specific primers and control primers (supplemental Table 1), as described.24

Metaphase spreads

BMDMs were incubated with colcemid (0.1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes to 1 hour. BMDMs were swelled in 0.56% KCl for 15 minutes at 37°C and then fixed in ice-cold fixative (methanol and acetic acid, 3:1) and washed several times in fixative. Metaphase preparations were spread on precleaned glass slides, dried at room temperature, and stained with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole in mounting medium.25 One hundred macrophages were scored per genotype.

Macrophage proliferation, cell cycle, and DNA content

Proliferation was measured as described.21 For cell cycle analysis, 106 cells were plated with 3 mL of 10% fetal calf serum Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium and incubated for 16 hours before the addition of stimulants. Cells were collected after 24 hours, fixed with 95% ethanol, incubated with propidium iodide (PI) and RNAse-A, and later analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunofluorescence

DNA breaks were quantified by counting the number of γH2AX foci per nuclei. For each condition, 10 different fields with at least 14 cells each were analyzed. The results are shown as the number of foci per nucleus in each field. The γH2AX antibody (EMD Millipore) was used with an Alexa-Fluor 488-labeled secondary antibody (Molecular Probes).

ROS

ROS production was measured by using dichlorofluorescin diacetate as described.24

Sterile inflammation

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 2 × 106 zymosan particles resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or with PBS alone.26 After 48 hours, mice were euthanized and peritoneal lavage was performed. The recovered cells were stained for extracellular CD11b and F4/80 prior to fixation and permeabilization. Cells were then stained for the intracellular proliferation marker Ki-67 with the PE Mouse Ki-67 Set (BD Biosciences). After washing, sample phenotypes were determined by flow cytometry.

Cutaneous inflammation

A solution of 0.5% 2,4-dinitrofluorobenezene (DNFB) in acetone was applied on the right ear of each mouse and acetone was applied on the left ear as a control.27 Animals were euthanized on day 7 after application. Ears were used for RNA and histology analysis after 24 hours of 4% paraformaldehyde fixation and paraffin embedding. Ear sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were collected with a Nikon E800 microscope, and maximum ear thickness measurements were calculated with Fiji software.

Flow cytometry

BMDMs were collected and 5 × 105 cells were analyzed by using anti-CD115-PE (phycoerythrin) (eBioscience), anti-Ly6C-FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate) (BD Pharmigen), anti-F4/80-APC (allophycocyanin) (eBioscience), anti-CD45-PECy7 (eBioscience), and anti-CD11b-BV711 (Biolegent) plus 4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole to exclude dead cells. To detect major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression, an anti-MHC II-FITC (BD Pharmigen) was used. Samples were acquired on a Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test with GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results

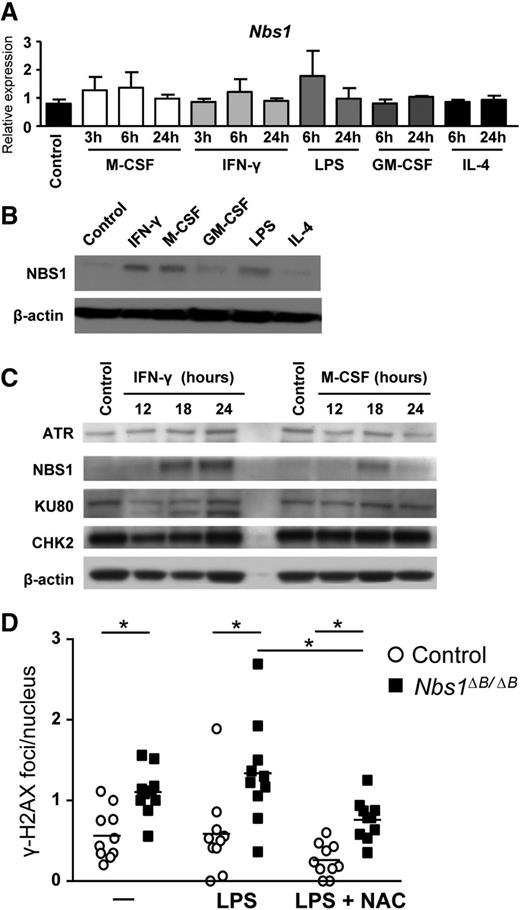

NBS1 levels in macrophages are regulated by proinflammatory stimuli and M-CSF

Despite the high levels of DNA damage that occur in macrophages, the impact of attenuated MRE11 complex function has not been investigated.28,29 To address this, we first examined the expression of Nbs1 in macrophages to determine whether it was modulated by different stimulatory agents. We obtained murine BM and differentiated it in vitro to BMDMs. The resulting homogenous population of cells was composed of quiescent primary macrophages that could be induced to proliferate by growth factors or that could be classically and alternatively activated by cytokines.30 BMDMs were incubated with different proinflammatory (IFN-γ and LPS), anti-inflammatory (IL-4), and proliferative stimuli (M-CSF and GM-CSF), and levels of NBS1 were determined after treatment. No significant changes in Nbs1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels (Figure 1A) were observed. However, after IFN-γ, LPS or M-CSF treatment, the levels of NBS1 protein were increased (Figure 1B). The changes in total NBS1 protein levels were specific, because the total levels of ATR, KU80, and CHK2 (other DSB-responsive proteins) were unaffected by macrophage stimulation (Figure 1C). To determine whether the increase was the result of the expression of alternative mRNA transcripts, we conducted a qualitative PCR analysis using primers that spanned the 2491-bp Nbs1 mRNA (NM_013752.3). In each case, we observed the same size and expression level, regardless of stimuli (supplemental Figure 1). Although the mechanism of protein stabilization during proinflammatory activation remained unclear, it suggested that NBS1 may have an important functional activity.

NBS1 is induced in macrophages after proinflammatory and M-CSF stimulation. Seven-day BMDMs were starved of growth factors for 16 to 18 hours and then incubated with different stimuli. IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) and LPS (10 ng/mL) were used as proinflammatory stimuli, IL-4 (10 ng/mL) as anti-inflammatory stimulus, and M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) as growth factors. (A) Relative mRNA expression was determined at the indicated times after treatment. Each graph represents triplicate samples, and the results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Protein levels of NBS1 were determined after 24 hours of stimulation. β-actin is included as a loading control. (C) Protein levels of other DNA damage response proteins were determined in macrophages upon stimulation with IFN-γ or M-CSF. β-actin is included as a loading control. (D) DNA damage was assessed by quantifying γH2AX foci. For each condition, 10 different fields with at least 14 cells each were quantified and the results are shown as number of foci per nucleus in each field. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger, was used at 1 mM. All assays are representative of at least 3 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .01 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

NBS1 is induced in macrophages after proinflammatory and M-CSF stimulation. Seven-day BMDMs were starved of growth factors for 16 to 18 hours and then incubated with different stimuli. IFN-γ (10 ng/mL) and LPS (10 ng/mL) were used as proinflammatory stimuli, IL-4 (10 ng/mL) as anti-inflammatory stimulus, and M-CSF (10 ng/mL) and GM-CSF (10 ng/mL) as growth factors. (A) Relative mRNA expression was determined at the indicated times after treatment. Each graph represents triplicate samples, and the results are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). (B) Protein levels of NBS1 were determined after 24 hours of stimulation. β-actin is included as a loading control. (C) Protein levels of other DNA damage response proteins were determined in macrophages upon stimulation with IFN-γ or M-CSF. β-actin is included as a loading control. (D) DNA damage was assessed by quantifying γH2AX foci. For each condition, 10 different fields with at least 14 cells each were quantified and the results are shown as number of foci per nucleus in each field. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), a ROS scavenger, was used at 1 mM. All assays are representative of at least 3 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .01 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

To address this, we used mice that express a hypomorphic allele of Nbs1, Nbs1∆B/∆B.20 We observed increased numbers of γH2AX foci, a marker of DNA breaks, in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, and they were further increased by treatment with LPS, which induced increased levels of ROS31 (Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 2). To determine whether ROS was required for the increased DSBs observed in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages, we added N-acetyl cysteine, a ROS scavenger. In both the wild-type (WT) and Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages, we observed a significant reduction in DSBs measured by γH2AX. This demonstrates that NBS1 is induced after macrophage activation and is critical for reducing DNA damage caused by increased ROS.

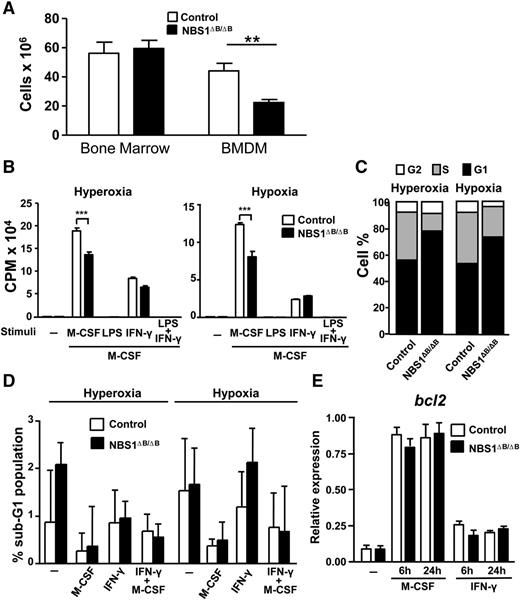

Nbs1 is required for M-CSF-dependent proliferation in macrophages

The MRE11 complex plays important roles in suppressing DNA damage during S phase.32 To examine the influence of the MRE11 complex on macrophage proliferation, we treated macrophages with M-CSF, which is crucial for both the differentiation and proliferation of macrophages.21 BM was extracted from 6- to 10-week-old WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, and cells were counted prior to incubation with M-CSF media for differentiation. Although the total number of BM cells obtained from WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice did not differ, the amount of differentiated macrophages obtained from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice after 7 days was approximately half that obtained from the WT littermates (Figure 2A).

Reduced proliferation of macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. (A) The number of total cells from the BM at day 0 of differentiation (BM after it was flushed from bones) and after 6 days of differentiation (in media containing M-CSF) from the indicated genotypes. (B) Macrophages were starved of growth factor for 18 hours, incubated for 1 hour with the indicated stimuli (LPS or IFN-γ), washed, and incubated for 24 hours with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) in a hyperoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) environment, and proliferation was quantified by incorporation of tritium. (C) Macrophages were starved of growth factor for 18 hours and incubated for 24 hours with M-CSF. Cell cycle distribution was determined by staining fixed cells with PI and assessment by flow cytometry. (D) Impaired NBS1 function does not induce cell death in macrophages treated with M-CSF or IFN-γ. Cells were treated as in (B), and viability was determined by using PI staining and flow cytometry. (E) The levels of Bcl2 mRNA expression were determined by qPCR in BMDMs treated with M-CSF or IFN-γ for the indicated times. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. **P < .01 and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

Reduced proliferation of macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. (A) The number of total cells from the BM at day 0 of differentiation (BM after it was flushed from bones) and after 6 days of differentiation (in media containing M-CSF) from the indicated genotypes. (B) Macrophages were starved of growth factor for 18 hours, incubated for 1 hour with the indicated stimuli (LPS or IFN-γ), washed, and incubated for 24 hours with M-CSF (10 ng/mL) in a hyperoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) environment, and proliferation was quantified by incorporation of tritium. (C) Macrophages were starved of growth factor for 18 hours and incubated for 24 hours with M-CSF. Cell cycle distribution was determined by staining fixed cells with PI and assessment by flow cytometry. (D) Impaired NBS1 function does not induce cell death in macrophages treated with M-CSF or IFN-γ. Cells were treated as in (B), and viability was determined by using PI staining and flow cytometry. (E) The levels of Bcl2 mRNA expression were determined by qPCR in BMDMs treated with M-CSF or IFN-γ for the indicated times. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. **P < .01 and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

Because M-CSF induced NBS1 protein levels (Figure 1B), we examined whether macrophage proliferation was affected in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. Once differentiated after 7 days in M-CSF, BMDMs were plated and deprived of M-CSF for 16 to 18 hours. Cells were subsequently treated for 1 hour with the indicated stimuli, washed, and further incubated with M-CSF for 24 hours, and proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages exhibited a decreased level of M-CSF-dependent proliferative capacity (Figure 2B). To eliminate the possibility that these differences were caused by an increase in DNA damage as a result of atmospheric ROS, experiments were repeated in a hypoxic chamber (1% O2), and similar differences were observed between macrophages from WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice (Figure 2B).

Because macrophage proliferation was affected in Nbs1∆B/∆B cells, we next evaluated the cell cycle distribution. After cell cycle synchronization by 18 hours of M-CSF withdrawal, cells were cultured in an M-CSF-rich environment for 24 hours. Cells were subsequently fixed and the DNA content was assessed with PI staining. This analysis demonstrated that the amount of Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages in S phase was reduced compared with WT macrophages in both hypoxic and hyperoxic conditions (Figure 2C and supplemental Figure 3), further corroborating the proliferative deficiency. This demonstrated that NBS1 was crucial for macrophage proliferation and cell cycle progression in vitro.

In addition to suppressing replication-associated DNA damage, the MRE11 complex is critical for apoptosis in various contexts, including oncogene activation and exogenous DNA damage.8,33-36 Therefore, we examined the impact of the Nbs1∆B allele on apoptosis in stimulated macrophages. Cells were incubated with M-CSF or IFN-γ for 24 hours, and sub-G1/G0 DNA was measured after PI staining. Sub-G1/G0 levels were very low and no significant differences were observed between WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B BMDMs (Figure 2D). The expression of Bcl2, a major proapoptotic gene, was also unaffected by genotype (Figure 2E). These results demonstrated that apoptosis was not affected by the Nbs1∆B/∆B allele in macrophages, consistent with previous results in lymphocytes and brain,35,36 and thus decreased proliferation was not a consequence of increased cell death.

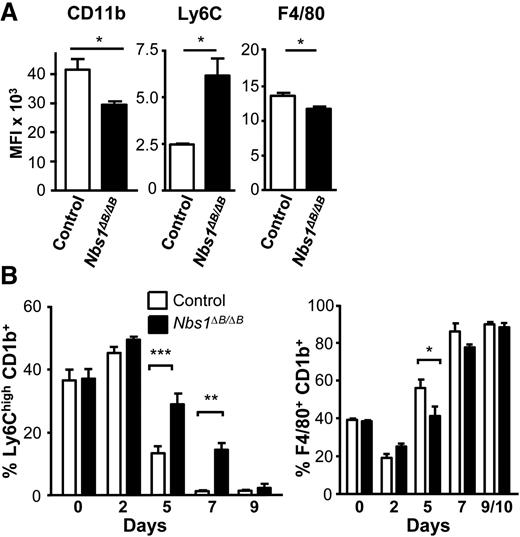

Delayed differentiation in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice

We then further examined the effect of the Nbs1∆B/∆B allele on macrophage differentiation. BMDMs were counted, and after 6 days in culture, they were stained with markers of macrophage differentiation, including CD11b, F4/80, and Ly6C. Macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice expressed lower levels of CD11b and F4/80 and higher levels of Ly6C (Figure 3A). The altered expression of these markers indicated impaired macrophage differentiation in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. We examined the expression levels of these differentiation markers during in vitro macrophage differentiation. After 7 days, in the CD11b+ population of control WT cells, the expression of Ly6Chigh marker disappeared. However, in cells from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, a significant difference in Ly6Chigh expression was observed after 7 days (Figure 3B), indicating that macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice have delayed maturation.

Impaired differentiation in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. Macrophages were differentiated from the BM of WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, and the surface expression of differentiation markers was determined by using antibodies and flow cytometry. (A) After 6 days of differentiation, cells were stained. (B) Time course of differentiation of Ly6ChighCD11b+ and F4/80+CD11b+ cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

Impaired differentiation in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. Macrophages were differentiated from the BM of WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, and the surface expression of differentiation markers was determined by using antibodies and flow cytometry. (A) After 6 days of differentiation, cells were stained. (B) Time course of differentiation of Ly6ChighCD11b+ and F4/80+CD11b+ cells. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared.

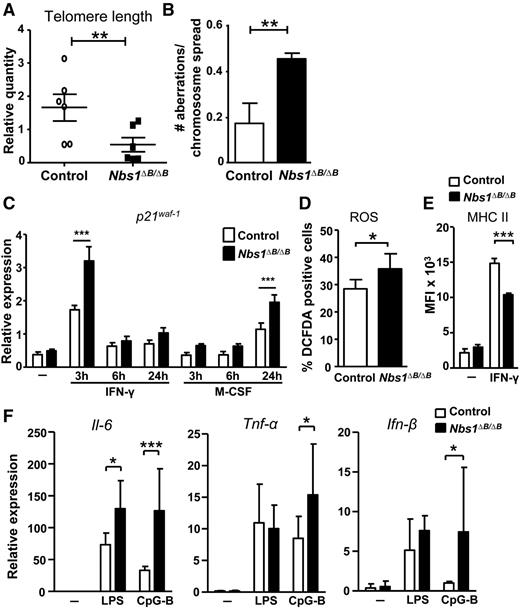

Increased senescence in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice

Cell cycle arrest and reduced proliferation, as well as cellular senescence, can be caused by DNA damage.37 To determine whether reduced proliferation of Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages was a result of increased DNA damage, we examined senescence markers. We analyzed telomere length by using real-time PCR and found that it was, on average, shorter in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages (Figure 4A). In addition, Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages exhibited higher levels of chromosomal aberrations when compared with control macrophages at day 7 (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 4), and this correlated with higher ROS levels (Figure 4D), reminiscent of the results in Figure 1D, in which Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages had increased γH2AX foci that were reduced upon treatment with N-acetyl-l-cysteine. Next, we assessed the mRNA levels of p21waf-1, which is induced by DNA damage and is considered a marker of senescence.38 p21waf-1 expression was determined by qPCR at different times after stimulation with either IFN-γ or M-CSF. In both cases, Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages showed a higher level of p21waf-1 (Figure 4C), although it was induced with different kinetics. After stimulation with IFN-γ, p21waf-1 expression peaked at 3 hours, and after stimulation with M-CSF, expression peaked at 24 hours. Previously, we showed that senescent macrophages have lower MHC II expression.39 Consistent with the other indicators of senescence, we found that MHC II surface expression decreased in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice (Figure 4E) after incubation of BMDMs with IFN-γ. Macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice treated with different proinflammatory cytokines showed increased expression of Il-6, Tnf-α and Ifn-β (Figure 4F). Collectively, these results suggested that increased DNA damage and impaired cell cycle progression in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice may impair differentiation and promote the induction of senescence.

Increased senescence in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. (A) Shorter average telomere length in Nbs1∆B/∆B BMDMs. DNA from BMDMs was extracted and relative telomere length was determined by qPCR. (B) Metaphase spreads were performed as indicated in the “Materials and methods” section. Quantification of metaphase aberrations in 100 cells per mouse is shown (n = 3). (C) The expression of p21waf-1 was determined by qPCR from BMDMs stimulated with proinflammatory (IFN-γ) or proliferative (M-CSF) stimuli for the indicated times. (D) BMDMs were stimulated with M-CSF for 30 hours, and ROS levels were determined by flow cytometry using dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA) as an indicator. (E) BMDM cells were activated with IFN- γ for 24 hours, and then the expression of MHC class II was determined by flow cytometry. (F) The macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice express higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines. BMDMs were incubated for 6 hours with the indicated stimuli, and the expression of Il-6, Ifn-β, and Tnf-α was determined by qPCR. Each point was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared. MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

Increased senescence in macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. (A) Shorter average telomere length in Nbs1∆B/∆B BMDMs. DNA from BMDMs was extracted and relative telomere length was determined by qPCR. (B) Metaphase spreads were performed as indicated in the “Materials and methods” section. Quantification of metaphase aberrations in 100 cells per mouse is shown (n = 3). (C) The expression of p21waf-1 was determined by qPCR from BMDMs stimulated with proinflammatory (IFN-γ) or proliferative (M-CSF) stimuli for the indicated times. (D) BMDMs were stimulated with M-CSF for 30 hours, and ROS levels were determined by flow cytometry using dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA) as an indicator. (E) BMDM cells were activated with IFN- γ for 24 hours, and then the expression of MHC class II was determined by flow cytometry. (F) The macrophages from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice express higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines. BMDMs were incubated for 6 hours with the indicated stimuli, and the expression of Il-6, Ifn-β, and Tnf-α was determined by qPCR. Each point was performed in triplicate and the results are shown as mean ± SD. All assays are representative of at least 4 independent experiments showing similar results. *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 in relation to the controls when all the independent experiments had been compared. MFI, mean fluorescent intensity.

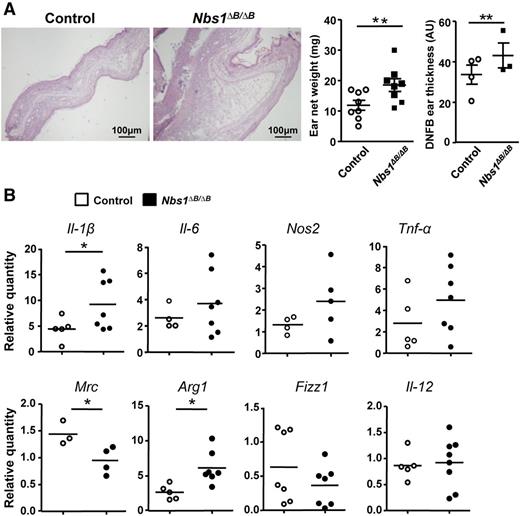

Enhanced inflammatory responses in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice

During inflammation, the numbers and functional activities of immune cells are crucial to mount an effective response. To determine whether the deficiencies we observed in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages had an effect on the immune response in vivo, we used the DNFB ear irritation model.27 Although the DNFB ear irritation model is not a macrophage-specific model, macrophages incorporated from the bloodstream play a critical role in the early stages of this inflammation as well as in its resolution.17 Mice were treated on the right ear with DNFB and on the left ear with acetone (control) and were euthanized after 7 days. Ears were punched at the inflammatory loci, the punch was weighed, and tissue was collected for histology and RNA extraction. Ear thickness was measured after H&E staining, and levels of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes were measured by qPCR. After treatment with DNFB, ears from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were heavier and thicker than those of WT littermates (Figure 5A). The mRNA levels of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory genes were also affected (Figure 5B). These results demonstrated that Nbs1∆B/∆B mice had an impaired immune response with an exacerbated proinflammatory response.

Exacerbated inflammation in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice treated with DNFB. (A) A representative sample of histologic images of DNFB-treated ears (at 7 day) is shown. At the right, the net weight of ears treated for 7 days with DNFB (8 mice) is shown. This was calculated by subtracting the weight of the DNFB-treated right ear from that of the acetone-treated left ear that was used as control. The ear thickness measurements were taken from the histologic images using Fiji software. Only DNFB-treated ear thickness is shown. AU, arbitrary unit. (B) Ear sample-derived mRNA was used to determine the expression of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers by qPCR. The results are shown as individual values and as the mean of the 8 WT and 8 Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. *P < .05 and **P < .01 in relation to the corresponding controls.

Exacerbated inflammation in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice treated with DNFB. (A) A representative sample of histologic images of DNFB-treated ears (at 7 day) is shown. At the right, the net weight of ears treated for 7 days with DNFB (8 mice) is shown. This was calculated by subtracting the weight of the DNFB-treated right ear from that of the acetone-treated left ear that was used as control. The ear thickness measurements were taken from the histologic images using Fiji software. Only DNFB-treated ear thickness is shown. AU, arbitrary unit. (B) Ear sample-derived mRNA was used to determine the expression of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory markers by qPCR. The results are shown as individual values and as the mean of the 8 WT and 8 Nbs1∆B/∆B mice. *P < .05 and **P < .01 in relation to the corresponding controls.

To examine the role of NBS1 in another in vivo model of inflammation, we used the intraperitoneal injection of zymosan, yeast fragments that bind TLR2, inducing peritonitis and triggering a rapid response of the immune system. At 24 hours to 60 hours after zymosan injection, macrophages are the most abundant cells accumulating at the peritoneal cavity.40 This is due to not only inflammatory macrophage recruitment but also to local macrophage proliferation that is M-CSF dependent.41 We injected zymosan into the peritoneal cavity of both WT and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice, and after 48 hours, we euthanized the mice and performed peritoneal lavages. The cells obtained were stained for CD11b, F4/80, and the intracellular proliferation marker Ki-67. By using flow cytometry, we differentiated proliferating macrophages from other proliferating cell types (Figure 6A). We injected PBS as a control, which did not affect the total number of proliferating cells or numbers of proliferating macrophages in WT or Nbs1∆B/∆B mice (Figure 6B). However, when we induced a sterile inflammation by zymosan injection, the percentage of macrophages was drastically decreased in the peritoneal cavity of Nbs1∆B/∆B mice (Figure 6B). Under these experimental conditions, we were unable to determine whether the cells that proliferate are of BM origin (moving from the blood) or from the peritoneal cavity. However, the analysis of peritoneal cells in vitro showed decreased proliferation in cells from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice (Figure 6C). Therefore, both BMDMs and peritoneal macrophage populations derived from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice showed impaired proliferative capacity.

Reduced macrophage proliferation from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice in a model of sterile inflammation. Control and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were injected in the peritoneal cavity with 2 × 106 zymosan particles or PBS (control). (A) Gating strategy of peritoneal cells after staining with anti-CD11b, anti-F4/80, and anti-Ki67 (cell marker for proliferation). FS-W, forward scatter–width; FSS, forward scatter signal; SS-A, side scatter–area. (B) The percentage of Ki-67+F4/80+ cells (macrophages) and Ki-67+F4/80– cells was determined for animals treated with either PBS or zymosan. For the control experiments, 7 control mice and 6 Nbs1∆B mice were used, and for the experiment with zymosan, 8 control mice and 7 Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were used. ***P < .001. (C) Proliferation of peritoneal macrophages. Macrophages were obtained by peritoneal lavage and purified by adhesion. Proliferation was determined by thymidine incorporation after 24 hours of incubation with M-CSF (n = 4). cpm, counts per minute. The results are shown as mean ± SD. *P < .01 in relation to the corresponding controls.

Reduced macrophage proliferation from Nbs1∆B/∆B mice in a model of sterile inflammation. Control and Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were injected in the peritoneal cavity with 2 × 106 zymosan particles or PBS (control). (A) Gating strategy of peritoneal cells after staining with anti-CD11b, anti-F4/80, and anti-Ki67 (cell marker for proliferation). FS-W, forward scatter–width; FSS, forward scatter signal; SS-A, side scatter–area. (B) The percentage of Ki-67+F4/80+ cells (macrophages) and Ki-67+F4/80– cells was determined for animals treated with either PBS or zymosan. For the control experiments, 7 control mice and 6 Nbs1∆B mice were used, and for the experiment with zymosan, 8 control mice and 7 Nbs1∆B/∆B mice were used. ***P < .001. (C) Proliferation of peritoneal macrophages. Macrophages were obtained by peritoneal lavage and purified by adhesion. Proliferation was determined by thymidine incorporation after 24 hours of incubation with M-CSF (n = 4). cpm, counts per minute. The results are shown as mean ± SD. *P < .01 in relation to the corresponding controls.

Discussion

After proinflammatory stimulation, macrophages produce increased ROS that are able to extensively damage DNA.42-44 Under these stimuli (IFN-γ or LPS), we detected increased levels of NBS1. In Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages, this stimulation led to increased DNA damage that could be strongly reduced by the addition of N-acetyl-l-cysteine, indicating that the MRE11 complex was important for suppressing ROS-induced DNA damage (Figure 1D). However, even in the absence of ROS-inducing stimuli, the basal levels of DNA breaks were higher in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages, potentially reflecting defects in DNA surveillance during the rapid proliferation that precedes differentiation. Consistent with this possibility, stimulation with M-CSF that leads to high levels of proliferation was accompanied by increased levels of chromatid breaks in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages (Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 2). The increased NBS1 protein levels observed in activated macrophages were the result of posttranscriptional regulation because we did not observe differences in mRNA levels after any of the treatments (Figure 1A). Because little is known regarding the regulation of NBS1 protein levels, further studies will be required to elucidate the mechanisms by which NBS1 levels are controlled in macrophages. We believe they are likely to be somewhat specific, because no differences were observed in the levels of other DDR proteins, including ATR, CHK2, and KU80, after stimulation. Together, our results suggest that the MRE11 complex is crucial for preventing DNA damage in macrophages during replication and after proinflammatory activation.

In mice, the complete deficiency of Nbs1 led to embryonic lethality.7 By using a mouse model expressing a hypomorphic allele of Nbs120 that does not compromise animal viability or accelerate mortality, we confirmed that NBS1 function was important for macrophage function because Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages showed impaired proliferation and delayed differentiation. This was accompanied by the induction of 2 of the classical markers associated with aging in macrophages, increased numbers of chromosomal aberrations and telomere shortening,24 as well as a lack of MHC II induction by IFN-γ39 and increased levels of p21, a marker of senescence. Given the roles of the MRE11 complex in DNA replication, cell cycle control, and telomere maintenance,7,45 we believe that this premature aging of macrophages is the most likely explanation for the reduced proliferation and delayed differentiation, because we did not observe changes in the induction of apoptosis, suggesting that cell cycle abnormalities were not the result of increased cell death.

Our in vitro observations suggested that the accumulation of increased DNA damage may compromise macrophage function and lead to premature attrition in vivo. Monocytes are more prone to DNA damage than dendritic cells and macrophages, exhibiting increased apoptosis upon ROS exposure resulting from impaired DSB repair.46 Because Nbs1∆B/∆B mice have defective DSB responses, it is possible that over time, DNA damage is accumulated in monocytes and macrophages.

Consistent with our observations in vitro, we also observed an enhanced inflammatory response in Nbs1∆B/∆B mice after treatment with DNFB. Persistent DNA damage has been linked to senescence and has been shown to trigger inflammatory cytokines, as we have observed in Nbs1∆B/∆B macrophages. This response has been termed the “senescence-associated secretory phenotype” or SASP, and its function has been linked to a variety of age-related pathological outcomes, including tumorigenesis and sterile chronic inflammation.47,48 Recent work has demonstrated that the MRE11 complex and ATM are critical for the innate immune response to cytosolic DNA in bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs)49,50 and in BMDMs.51 In response to cytosolic DNA generated by increased DNA damage or polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid, BMDCs activate the STING pathway to trigger SASP-inducing inflammatory pathways mediated by IL-1β and the inflammosome.49,50 In this context, cytosolic DNA sensing has been attributed to ATM and interactions between RAD50 and the CARD9 protein.49 The Nbs1∆B allele leads to mislocalization of some of the MRE11-RAD50 pool to the cytoplasm and therefore may lead to both increased cytosolic DNA and enhanced signaling in BMDCs, because NBS1 is not strictly required for the cytosolic responses.49

In addition to the MRE11 complex and ATM, a number of additional cytosolic nucleic acid sensors have been identified and are associated with the suppression of type I IFN production. This includes Trex1, which is mutated in systemic lupus erythematosus and implicated in the DNA damage response.52,53 We recently reported enhanced proinflammatory activation in macrophages from mice lacking Trex1,22 and the release of cytokines has been attributed to phenotypic variations in patients with Aicardi-Goutières syndrome.54 Mutations that lead to activation of innate immunity by inducing the secretion of type I IFN collectively may represent “interferonopathies”,55 disorders that are characterized by neurologic and dermatologic features provoked by autoimmunity.

The SASP likely shares many common features with the interferonopathies. Both may originate from the malfunction of proteins involved in responding to DNA damage that can trigger large amounts of both type I IFNs and inflammatory cytokines, and their co-occurrence may be important to consider in human disease. These findings suggest the relationship between the SASP and IFN response and the role of the DNA damage response should be examined further in different types of immune cells.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that NBS1 plays an important role in macrophage differentiation, proliferation, and inflammatory responses in vivo. Here we have described what is, to the best of our knowledge, the first functional macrophage defects resulting from mutations in Nbs1. Because NBS patients present with immunodeficiency, which is a major health threat to these patients, a complete understanding of the role of the MRE11 complex in immune system development and homeostasis is essential and the role of macrophages in NBS pathology should be further considered.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Gemma Lopez, Natalia Plana, Lluis Palenzuela, and Jaume Comas for their excellent technical assistance and Andre Nussenzweig and Elsa Callen for reagents.

This work was supported by Formación del Profesorado Universitario grants AP2010-5396 (S.P.-L.) and AP2012-02327 (J.T.) from the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, by Formación del Personal Investigador grant BES-2012-055074 (J.A.C.-S.) from the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (MINECO), and by grants BFU2012-39521 (T.H.S.) and BFU2011-23662 (A.C.) from the MINECO.

Authorship

Contribution: S.P.-L. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.T. and J.A.C.-S. performed research; J.L. designed the research; and T.H.S. and A.C. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Antonio Celada, Parc Cientific of Barcelona, Baldiri Reixac 10, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; e-mail: acelada@ub.edu.