Abstract

Background

Despite the constant improvement in the outcome of allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (allo-HSCT) for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), relapses remain frequent, warranting investigation on their biological bases.

After haploidentical HSCT up to one third of AML relapses feature selective genomic loss of the HLA haplotype targeted by alloreactive donor T cells (Vago, N Engl J Med, 2009; Crucitti, Leukemia, 2015), evading their control and gaining the ability to outgrow.

Yet, Natural Killer (NK) cells mediate alloreactivity in response to loss of specific HLA allotypes from target cells: thus, in theory, HLA loss relapses should represent excellent targets for donor NK cell recognition. Here we investigated the dynamics of NK cells in this unique immunogenetic context, to understand the biological bases of their failure in preventing the emergence of HLA loss variants.

Methods

We took into consideration 23 patients who after T cell replete haploidentical HSCT experienced HLA loss relapses. NK cell alloreactivity was predicted according to the Perugia algorithm (Ruggeri, Science, 1999). Killer Cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptor (KIR) typing was performed using a commercially-available kit, and KIR B-content estimated using the EMBL-EBI calculator. The phenotypic features of peripheral blood NK cells were assessed by multiparametric flow cytometry, and high dimensional single-cell analysis was performed using the viSNE bioinformatic tool.

Results

Based on donor-recipient HLA typing, at the time of HSCT NK cell alloreactivity in the graft-versus-leukemia direction was predicted in 10/23 patients who experienced HLA loss relapses (43.5%). In 7/23 additional patients (30.4%), conditions for predicted NK cell alloreactivity were fulfilled at time of relapse, upon genomic loss of the mismatched HLA haplotype from AML blasts. In all cases KIR genotyping confirmed the presence in the donor repertoire of the necessary KIR genes. Only 3/17 HSC donors were homozygous for KIR A haplotypes, encoding preferentially inhibitory KIR genes, and most carried equal or higher numbers of activating KIR genes than expected (Cooley, Blood, 2010). Thus, the absence of NK cell-mediated control of HLA loss variants can not be explained by an unfavorable immunogenetic asset of HSC donors.

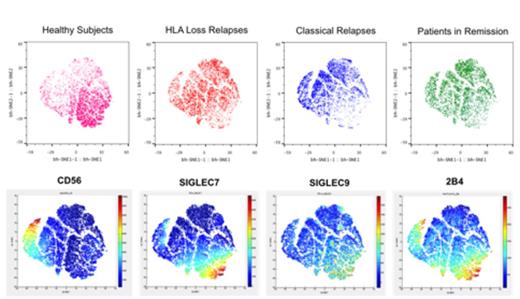

Therefore we characterized the phenotypic features of NK cells circulating in the peripheral blood of 7 patients at the time of HLA loss relapse (median time after HSCT 307 days, range 147-703), and compared them to their counterparts in healthy individuals (n=6), and matched-paired transplanted patients in remission (n=6), or at the time of non HLA loss ("classical") relapse (n=7). We analyzed a total of 27 markers involved in NK cell target recognition (KIRs, NKG2A, NKG2C, SIGLEC7, SIGLEC9), activation (NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, NKG2D, 2B4, DNAM1), maturation (CD57, CD16, CD62L), and exhaustion (PD1, TIM3, KLRG1). At the time of HLA loss relapse, NK cells had recovered a mature phenotype, although with a slightly higher frequency of CD56bright cells. In all cases in which NK cell alloreactivity had been predicted we detected the single-KIR+ NK cells of interest, without significant differences between patients and controls. However NK cells from transplanted patients expressed lower levels of the SIGLEC9 (p<0.0001) and SIGLEC7 (p=0.03) receptors as compared to healthy individuals, suggesting impaired antitumor activity (Jandus , J Clin Invest, 2014), and higher levels of exhaustion markers including TIM3 (p=0.03). Accordingly, viSNE maps demonstrated differential clustering of NK cells between patients and healthy subjects, mainly explained by the aforementioned differences.

Conclusions

Even at late timepoints after partially-incompatible allo-HSCT, when HLA loss relapses typically occur, the reconstituted NK cell repertoire displays profound differences from its counterpart in healthy subjects, hinting for defective immunosurveillance. Therapeutic protocols employing freshly isolated mature donor NK cells should thus be further investigated for the prevention and treatment of HLA loss relapses.

The same viSNE map, obtained by analysis of the entire dataset, is differentially colored to evidence the spatial distribution, and thus phenotypic similarity, of NK cells from each cohort (upper row) or the intensity of expression of the indicated markers (lower row).

The same viSNE map, obtained by analysis of the entire dataset, is differentially colored to evidence the spatial distribution, and thus phenotypic similarity, of NK cells from each cohort (upper row) or the intensity of expression of the indicated markers (lower row).

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.

This icon denotes a clinically relevant abstract