In this issue of Blood, Emile et al, representing the Histiocyte Society (HS), have proposed a revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell (DC) lineages, taking into account recent insights regarding cell of origin, molecular genetics, and clinical features.1

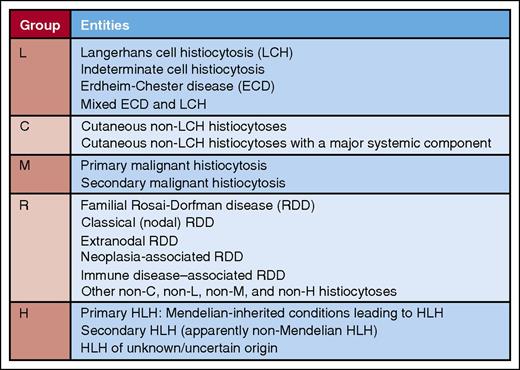

Summary of entities comprising the L, C, M, R, and H groups in the revised classification of Emile et al for the HS. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Summary of entities comprising the L, C, M, R, and H groups in the revised classification of Emile et al for the HS. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

For pathologists and clinicians, even those with special expertise in hematologic diseases, reactive and neoplastic proliferations of cells in the histiocytic, monocyte/macrophage, and DC lineages can be tremendously difficult to diagnose. Because many of the entities that comprise this collection of diseases are extremely rare, the combined experience of a number of institutions is useful to clinicians and others interested in the histiocytoses. This has been done before, notably by the Working Group of the HS in 1987.2

But a new perspective on these diseases would be desirable, in particular one that takes into account the advances in our knowledge of the pathology, clinical presentation, and molecular genetic features of these entities that have occurred in recent years. This is admirably accomplished by Emile et al in their article, which represents the efforts of members of the HS, which includes researchers at 26 different institutions from Europe and North America. They categorize the entities into 5 groups, designated L (Langerhans), C (cutaneous and mucocutaneous), M (malignant), R (Rosai-Dorfman), and H (hemophagocytic) (see figure). Some of the numerous insights and recommendations from the article are summarized, particularly those that relate to recent breakthroughs.

The L group includes Langerhans cell (LC) histiocytosis (LCH) and Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD), entities with similar immunophenotypes (∼20% of cases of ECD have LC lesions) having recently been shown to have mutations in the MAPK pathway in >80% of cases. BRAF p.V600E mutations, identified in ∼50% of cases of LCH and ECD, result in constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway.3,4 Mutations in MAP2K1 (MEK1), another component of the MAPK pathway, are identified in ∼19% of LCH, including BRAF mutation–negative cases.5 The authors recommend BRAF and MAP2K1 analysis to confirm difficult cases of LCH and ECD and in patients who fail first-line treatment.

The C group, which consists of entities with a predominance of skin/mucosal involvement, is an adaptation of the 2005 classification of Weitzman and Jaffe, taking into account immunophenotypic and clinical features.6

In their discussion of the M group, the authors correctly observe that a major problem for diagnosticians is the absence of specific criteria indicative of malignancy in histiocytes. They therefore recommend that the diagnosis of malignant histiocytosis (MH) should be reserved for those patients with rapidly progressing tumors. The recent identification of frequent chromosomal gains and losses in MH, in contrast to LCH, which usually is karyotypically normal and has <5 somatic mutations, points to the potential usefulness of molecular genetic techniques in resolving difficult cases.7 Secondary proliferations of malignant histiocytes have been identified in association with other hematologic malignancies. In some cases, a clonal relationship to the primary malignancy has been established using immunoglobulin gene rearrangement studies, BRAF mutational analysis, or another translocation or chromosomal abnormality between the primary and secondary malignancies.8

The R group, which consists in large part of Rosai-Dorfman disease, is usually straightforward diagnostically because of the characteristic cytomorphologic and immunophenotypic properties of the histiocytes. However, caution should be exercised in central nervous system disease, in which the clinical and radiographic appearance can simulate meningioma, and in cases with large numbers of IgG4+ plasma cells, in which IgG4-related disease must be excluded.9

Entities included in the H (hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis [HLH]) group share the common clinical features of uncontrolled immune activation including fever, cytopenias, hepatosplenomegaly, and hyperferritinemia. Primary HLH is related to known inherited immune disorders with dysregulation of the inflammasome. Secondary HLH may be associated or triggered by an infection, connective tissue disorder, or malignancy. Interestingly, some cases of secondary HLH have recently been associated with mutations which impair cytolysis, potentially blurring the distinction between primary and secondary HLH.10

In summary, the authors and the HS are to be commended for their efforts to synthesize the ∼100 categories of histiocyte disorders into a useful, informative, and up-to-date classification schema that includes practical recommendations for the diagnostician and the results of recent research in the field. And sometimes, the answers reveal more questions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.