Key Points

Bone marrow stromal cell–derived IL-6 induces Mcl-1 dependence through transcriptional and posttranslational changes in the Bcl-2 family.

Blocking IL-6 signaling pathways sensitizes myeloma to inhibitors of Bcl-2 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL.

Abstract

Multiple myeloma is highly dependent on the bone marrow microenvironment until progressing to very advanced extramedullary stages of the disease such as plasma cell leukemia. Stromal cells in the bone marrow secrete a variety of cytokines that promote plasma cell survival by regulating antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family including Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2. Although the antiapoptotic protein on which a cell depends is typically consistent among normal cells of a particular phenotype, Bcl-2 family dependence is highly heterogeneous in multiple myeloma. Although normal plasma cells and most multiple myeloma cells require Mcl-1 for survival, a subset of myeloma is codependent on Bcl-2 and/or Bcl-xL. We investigated the role of the bone marrow microenvironment in determining Bcl-2 family dependence in multiple myeloma. We used the Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor ABT-737 to study the factors regulating whether myeloma is Mcl-1 dependent, and thus resistant to ABT-737–induced apoptosis, or Bcl-2/Bcl-xL codependent, and thus sensitive to ABT-737. We demonstrate that bone marrow stroma is capable of inducing Mcl-1 dependence through the production of the plasma cell survival cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). IL-6 upregulates Mcl-1 transcription in a STAT3-dependent manner, although this occurred in a minority of the cells tested. In all cells, IL-6 treatment results in posttranslational modification of the proapoptotic protein Bim. Phosphorylation of Bim shifts its binding from Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL to Mcl-1, an effect reversed by MEK inhibition. Blocking IL-6 or downstream signaling restored Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence and may therefore represent a clinically useful strategy to enhance the activity of Bcl-2 inhibitors.

Introduction

Long-lived plasma cells can survive in the bone marrow and produce antigen-specific antibodies for decades even in the absence of repeat antigen exposure.1 Survival of these cells is governed by a family of proteins that includes antiapoptotic members such as Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1, as well as proapoptotic members such as Bim. The antiapoptotic proteins bind to and sequester Bim, preventing it from activating apoptotic effector proteins Bax and Bak in the mitochondrial membrane.2,3 Despite coexpression of multiple antiapoptotic proteins, plasma cells depend primarily on Mcl-1 for survival. Treatment of mice with ABT-737, a compound that inhibits Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, results in a significant loss of B cells but has minimal impact on preexisting plasma cells.4 Furthermore, conditional deletion of Mcl-1 leads to dramatic reduction in the number of bone marrow plasma cells.5,6

As cells undergo malignant transformation, they must overcome a number of proapoptotic signals in order to survive, leaving them even more dependent upon antiapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, and thus susceptible to Bcl-2 family inhibitors such as venetoclax (ABT-199), a Bcl-2 specific inhibitor, and navitoclax (ABT-263), a Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor.7 Despite the numerous changes that occur during transformation, malignant plasma cells tend to remain dependent on Mcl-1 as demonstrated by the use a small-molecule Mcl-1 inhibitor and small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of Mcl-1.8,9 However, treatment of myeloma patient samples and human myeloma cells lines with venetoclax or ABT-737 revealed that a subset of myeloma is sensitive to these drugs and must therefore be Bcl-2/Bcl-xL codependent.9-13

In addition to preserving Mcl-1 dependence, myeloma also remains highly dependent on the bone marrow microenvironment. Bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) provide survival signals through adhesion molecules and secretion of cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor. These cytokines contribute to myeloma survival by activating numerous signaling pathways.14 The tumor necrosis factor family members B cell activating factor (BAFF) and a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) also promote plasma cell survival,15,16 and along with IL-6 have been reported to increase expression of Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL.5,17-23 However, we have previously demonstrated that expression of Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 alone cannot account for Bcl-2 family dependence. Instead, preferential binding of Bim to Mcl-1 vs Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL correlates with ABT-737 sensitivity more consistently.9 We therefore set out to understand how the stromal microenvironment influences myeloma dependence on Bcl-2 family proteins.

Methods

Cell lines

RPMI8226 (8226) and Hs-5 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. KMS11 and KMS12BM were purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank. MM.1s was provided by Steven Rosen (City of Hope), KMS18 by Leif Bergsagel (Mayo Clinic), OCI-My5 by Jonathan Keats (TGen), and OPM2 by Nizar Bahlis (University of Calgary). All cell lines were validated using sequencing and phenotypic characterization.

Cellular assays

Hs-5 and patient-derived BMSCs were plated 48 hours prior to collection of conditioned media, which was then filtered using a 0.2 micron syringe filter, diluted to the appropriate concentration with complete RPMI, and used to resuspend myeloma cells. Myeloma cells were incubated in conditioned media for 30 minutes prior to addition of drug. Myeloma cells cocultured with either Hs-5 cells or patient-derived BMSCs were added to preplated stromal cells in fresh media (following removal of the conditioned media) and given 30 minutes to attach before treatment. For IL-6 blocking experiments, antibodies were added directly to control and conditioned media at least 30 minutes before cell resuspension.

Reagents

Cells were treated with U0126, LY294002 (Cell signaling), AZD1480, ruxolitinib (Selleckchem), recombinant human IL-6, anti-IL-6 antibody, and anti-IL-6R antibody (R&D systems). ABT-737 and ABT-199 were generously provided by AbbVie.

Apoptosis assays

Cell death was measured by annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (PI) staining as previously described.24

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used for western blot: Bim (EMD Millipore); Mcl-1 (Enzo Life Sciences); Bcl-2 (BD Biosciences); β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich); Bcl-xL, phospho-Ser69 Bim, phospho-Ser77 Bim, phospho-extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204), Erk1/2, phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705), STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology). For coimmunoprecipitation, the following antibodies were used: Mcl-1, Bcl-2 (BD Biosciences); Bcl-xL (7B2.5)25 ; and Bim (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary anti-mouse immunoglobulin G–horseradish peroxidase (IgG-HRP), anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-hamster IgG-HRP (BD Biosciences) were used for western blotting. CD138-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), CD45-allophycocyanin-Cy7, and CD38-phycoerythrin (BD Biosciences) were used for flow cytometry.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed using standard techniques as previously described.26

Coimmunoprecipitation studies

Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed using the Exacta-Cruz C Kit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) following the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described.26

siRNAs

siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon (GE Life Sciences). ON-TARGETplus SMART pool siRNA against STAT3 and the siCONTROL nontargeting siRNA were used per manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Real time was performed as previously described26 using Applied Biosystems High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies) and amplified using the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Life Technologies) on the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System following the manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems).

Patient sample processing

All samples were collected following an Emory University Institutional Review Board–approved protocol as previously described.9

Results

The presence of stromal cells decreases codependence on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL in multiple myeloma

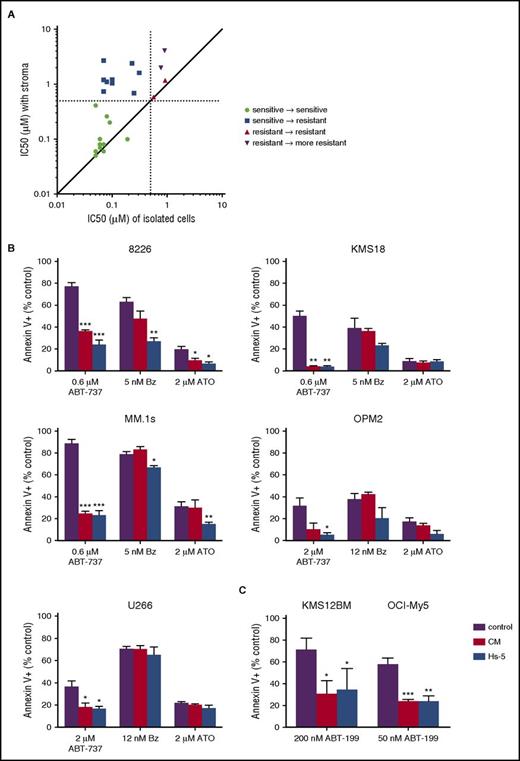

In order to evaluate the role of stromal cells in Bcl-2 family dependence, we compared the response of patient myeloma cells to ABT-737 either in the presence or absence of stromal cells obtained from the same bone marrow aspirate. Cells codependent on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL are sensitive to ABT-737–induced cell death, defined by an 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of <0.5 μM, whereas cells not dependent on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL are resistant to ABT-737. Freshly isolated bone marrow aspirates from myeloma patients were divided into 2 fractions, one containing unmanipulated plasma cells and stromal cells, and a second subjected to magnetic bead separation to isolate a pure population of CD138+ plasma cells. Both fractions were then treated with increasing concentrations of ABT-737 to determine an IC50 value with and without stromal cells. The presence of stromal cells reduced the degree of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence in myeloma cells in a large fraction of the samples (Figure 1A). In 14 of the 24 samples tested, the IC50 increased by more than twofold in the presence of stromal cells, increasing in 1 sample by almost 40-fold. Furthermore, in 9 of the ABT-737–sensitive CD138+ selected samples, the presence of stroma increased the IC50 to >0.5 μM, indicating that the myeloma was no longer Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependent. These data therefore suggest that stroma-derived signals drive loss of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL codependence and are a potentially important source of resistance to Bcl-2 inhibitors.

Stromal cells decrease Bcl-2/Bcl-xLdependence of multiple myeloma. (A) Myeloma patient bone marrow aspirates were divided into either a buffy coat fraction containing myeloma and stromal cells or CD138+ purified myeloma cells and then treated with increasing concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours. Apoptosis of myeloma cells was measured by flow cytometry following staining for annexin V-FITC to calculate the IC50 under the 2 conditions. Plasma cells were identified by staining with CD38 and CD45 (CD38+, CD45−). The IC50 of myeloma in the presence of stromal cells is plotted along the y-axis, and the IC50 of CD138+ purified cells is plotted on the x-axis. Each dot represents a single patient sample. Dashed lines represent the cutoff for ABT-737 sensitivity at 0.5 μM. (B) Hs-5 stromal cells and conditioned media induce resistance to ABT-737 but not bortezomib or arsenic trioxide in myeloma cell lines. MM.1s, 8226, KMS18, OPM2, and U266 were treated with the indicated drugs and concentrations for 24 hours in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (50%) before staining with CD38 to identify plasma cells and annexin V to measure apoptosis. (C) KMS21BM and OCI-My5 were treated with ABT-199 at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (50%) before staining with CD38 to identify plasma cells and annexin V to measure apoptosis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

Stromal cells decrease Bcl-2/Bcl-xLdependence of multiple myeloma. (A) Myeloma patient bone marrow aspirates were divided into either a buffy coat fraction containing myeloma and stromal cells or CD138+ purified myeloma cells and then treated with increasing concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours. Apoptosis of myeloma cells was measured by flow cytometry following staining for annexin V-FITC to calculate the IC50 under the 2 conditions. Plasma cells were identified by staining with CD38 and CD45 (CD38+, CD45−). The IC50 of myeloma in the presence of stromal cells is plotted along the y-axis, and the IC50 of CD138+ purified cells is plotted on the x-axis. Each dot represents a single patient sample. Dashed lines represent the cutoff for ABT-737 sensitivity at 0.5 μM. (B) Hs-5 stromal cells and conditioned media induce resistance to ABT-737 but not bortezomib or arsenic trioxide in myeloma cell lines. MM.1s, 8226, KMS18, OPM2, and U266 were treated with the indicated drugs and concentrations for 24 hours in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (50%) before staining with CD38 to identify plasma cells and annexin V to measure apoptosis. (C) KMS21BM and OCI-My5 were treated with ABT-199 at the indicated concentrations for 24 hours in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (50%) before staining with CD38 to identify plasma cells and annexin V to measure apoptosis. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE) of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001).

To corroborate our patient sample findings, we cultured a panel of 7 human myeloma cell lines with the Hs-5 stromal cell line and treated the cells with ABT-737. Using Mcl-1 siRNA knockdown, coimmunoprecipitation, and ABT-737 sensitivity, we have previously shown that MM.1s, 8226, and KMS18 are codependent on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL and Mcl-1, whereas OPM2 and U266 are primarily Mcl-1 dependent, dying with only high concentrations of ABT-737.9 KMS12BM and OCI-My5 are highly sensitive to ABT-199 and thus Bcl-2 dependent (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood Web site). In all 7 cell lines, the presence of stromal cells inhibited apoptosis induced by ABT-737 or ABT-199 (Figure 1B-C). Stromal cells had little to no effect on bortezomib- and arsenic trioxide–treated cells, arguing that stromal cell protection is specific to the mechanism of action of ABT-737 (Figure 1B). These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that the effectiveness of bortezomib and arsenic trioxide are independent of Bcl-2 family dependence or target Mcl-1 by upregulating Noxa.26-28 Culturing the cell lines with Hs-5 conditioned media resulted in equivalent levels of protection from ABT-737 compared with Hs-5 cells, suggesting that a secreted factor is contributing to loss of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence. We obtained similar results when culturing MM.1s with stromal cells and conditioned media from 4 different myeloma patient samples (supplemental Figure 2).

Blocking IL-6 restores Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence in the presence of stroma

IL-6 is a known stromal-derived plasma cell survival cytokine. We therefore hypothesized that IL-6 may be a component of the conditioned media responsible for reducing Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence and ABT-737 sensitivity. Indeed, addition of 10 ng/mL recombinant human IL-6 protected cells from ABT-737 much like conditioned media and stromal cells (Figure 2A). Conversely, blocking IL-6 with a neutralizing antibody reversed the protective effects of Hs-5 conditioned media (Figure 2B). When cells are cultured in 0.5% conditioned media, reversing IL-6–induced loss of Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence can be achieved either with a neutralizing antibody or by antagonizing the IL-6 receptor. However, in the presence of 50% conditioned media or stromal cells, the combination of IL-6 neutralization and IL-6 receptor blockade was more effective than either alone (Figure 2C). Normal BMSCs were also able to reduce Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence and rescue MM.1s cells from ABT-737–induced apoptosis, confirming that these results are not an artifact of using an immortalized stromal cell line or changes in the stroma of myeloma patients (Figure 2D). Similar to the findings with Hs-5, IL-6 neutralization partially reversed the protective effect of freshly isolated stromal cells. Finally, freshly isolated plasma cells from myeloma patients behaved similarly to MM.1s. IL-6 reduced the cell death with ABT-737 in isolated plasma cells while an IL-6 neutralizing antibody partially reversed the protective effect of coculture with stromal cells (Figure 2E). A second stromal-derived cytokine, IGF-1, had little to no effect on ABT-737–induced apoptosis, suggesting IL-6 is unique in its ability to inhibit Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence (supplemental Figure 3).

Stroma-derived IL-6 reduces Bcl-2/Bcl-xLdependence. (A-C) MM.1s was treated with the indicated concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours, and myeloma cell death determined by staining with annexin V-FITC and CD38. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001). (A) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells, Hs-5 conditioned media (CM, 50%), conditioned media from the stromal cells of a myeloma patient (BMSC CM, 50%), or IL-6 (10 ng/mL). (B) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 conditioned media (0.5%) and the indicated concentrations of neutralizing IL-6 antibody. (C) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (0.5% or 50%) and the neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody and/or anti-IL-6 receptor blocking antibody. (D) MM.1s was incubated with BMSCs from a normal donor (NBMSC) in the presence or absence of a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody (30 μg/mL) and treated with the indicated concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours. Myeloma cell death was determined by staining with annexin V-FITC and CD38. (E) CD138+ plasma cells (IPC) purified from a myeloma patient bone marrow aspirate were treated with ABT-737 and IL-6 (10 ng/mL). The total pool of mononuclear cells isolated by Ficoll separation (BCPC) were also treated with ABT-737 and a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody (30 μg/mL). Cell viability was determined by flow cytometry after staining with annexin V-FITC. Plasma cells were identified by staining with CD38 and CD45 (CD38+, CD45−).

Stroma-derived IL-6 reduces Bcl-2/Bcl-xLdependence. (A-C) MM.1s was treated with the indicated concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours, and myeloma cell death determined by staining with annexin V-FITC and CD38. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001). (A) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells, Hs-5 conditioned media (CM, 50%), conditioned media from the stromal cells of a myeloma patient (BMSC CM, 50%), or IL-6 (10 ng/mL). (B) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 conditioned media (0.5%) and the indicated concentrations of neutralizing IL-6 antibody. (C) Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of Hs-5 cells or conditioned media (0.5% or 50%) and the neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody and/or anti-IL-6 receptor blocking antibody. (D) MM.1s was incubated with BMSCs from a normal donor (NBMSC) in the presence or absence of a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody (30 μg/mL) and treated with the indicated concentrations of ABT-737 for 24 hours. Myeloma cell death was determined by staining with annexin V-FITC and CD38. (E) CD138+ plasma cells (IPC) purified from a myeloma patient bone marrow aspirate were treated with ABT-737 and IL-6 (10 ng/mL). The total pool of mononuclear cells isolated by Ficoll separation (BCPC) were also treated with ABT-737 and a neutralizing anti-IL-6 antibody (30 μg/mL). Cell viability was determined by flow cytometry after staining with annexin V-FITC. Plasma cells were identified by staining with CD38 and CD45 (CD38+, CD45−).

IL-6 increases Mcl-1 priming without altering Mcl-1 expression

IL-6 has previously been reported to affect the expression of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members such as Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2.17,19-23 To determine how IL-6 regulates these proteins in KMS18 and MM.1s, we examined changes in protein expression with IL-6, conditioned media, and Hs-5 cells. None of the 3 conditions altered expression of Bim, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1 in MM.1s (Figure 3A). However, we did observe increased Mcl-1 protein expression with these treatments in KMS18 (Figure 3B). To better understand IL-6 induced changes, we treated 5 cell lines with IL-6 and quantitated protein expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 by western blot. IL-6 exposure resulted in a statistically significant increase in Mcl-1 protein in only 1 of the 5 cell lines (KMS18; Figure 3C-D). Bcl-2 protein decreased by less than twofold in 2 of the 5 cell lines, whereas Bcl-xL protein levels did not change in any of the cell lines. We also measured the effects of IL-6 on messenger RNA (mRNA) levels (Figure 3E). In KMS18 (Mcl-1) and MM.1s (Bcl-2), IL-6 induced changes in mRNA reflected the changes we observed at the protein level. Interestingly, similar changes in Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 mRNA were present in additional cell lines, and Bcl-xL mRNA also decreased with IL-6 treatment in all 5 lines (supplemental Figure 4A); however, these did not translate into significant protein level changes (Figure 3C). This suggests that although IL-6 signaling may be similar in these lines, the impact of transcriptional changes is limited, although the lack of change in Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL protein may be related to the longer half-life of these proteins.29,30 We confirmed that IL-6 is highly active in all 5 cell lines by demonstrating significant upregulation of SOCS3 RNA, a known STAT3 target (supplemental Figure 4B).31

IL-6 regulates Bcl-2 family expression and binding to Bim. MM.1s (A) and KMS18 (B) cells were cocultured with Hs-5 cells, 50% conditioned media from Hs-5 cells, or treated with 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours. Lysates were prepared and subject to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by western blotting for Bim, Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, and actin. (C) The 8226, KMS18, MM.1s, OPM2, and U266 cells were treated with 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours. Cells were then lysed for protein and western blotting or RNA and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). A representative western blot of 3 independent experiments is shown. (D) Changes in protein expression were quantitated by densitometry after normalizing to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels. (E) RNA expression of Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 were measured using qRT-PCR. Both graphs depict the mean percent change ± SE relative to untreated cells (*P < .05 by the 1 sample Student t test). (F) MM.1s and KMS18 were treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours, and protein lysates were prepared then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-Bcl-2 antibodies. The resulting protein complexes and protein input (WCL) were examined by western blot analysis using anti-Bim, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-Bcl-2. The proportion of Bim bound to Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 was quantitated by densitometry and is represented as a pie chart for each condition. Each pie chart is the average of 3 independent experiments.

IL-6 regulates Bcl-2 family expression and binding to Bim. MM.1s (A) and KMS18 (B) cells were cocultured with Hs-5 cells, 50% conditioned media from Hs-5 cells, or treated with 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours. Lysates were prepared and subject to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by western blotting for Bim, Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, and actin. (C) The 8226, KMS18, MM.1s, OPM2, and U266 cells were treated with 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours. Cells were then lysed for protein and western blotting or RNA and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). A representative western blot of 3 independent experiments is shown. (D) Changes in protein expression were quantitated by densitometry after normalizing to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels. (E) RNA expression of Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 were measured using qRT-PCR. Both graphs depict the mean percent change ± SE relative to untreated cells (*P < .05 by the 1 sample Student t test). (F) MM.1s and KMS18 were treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours, and protein lysates were prepared then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-Bcl-2 antibodies. The resulting protein complexes and protein input (WCL) were examined by western blot analysis using anti-Bim, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, and anti-Bcl-2. The proportion of Bim bound to Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 was quantitated by densitometry and is represented as a pie chart for each condition. Each pie chart is the average of 3 independent experiments.

The shift in expression from Bcl-2 to Mcl-1 could potentially explain the IL-6–induced resistance to ABT-737 in KMS18 because ABT-737 does not inhibit Mcl-1. However, we have previously shown that expression levels alone cannot account for Bcl-2 family dependence.9 Despite coexpression of multiple antiapoptotic proteins, Bim preferentially binds to certain antiapoptotics in a cell-specific manner as demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation. In MM.1s, Bim binding to Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL is greater, making the cells Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependent and ABT-737 sensitive, whereas in U266, Bim is almost exclusively bound to Mcl-1, making it Mcl-1 dependent and insensitive to ABT-737.9 We performed similar coimmunoprecipitation experiments in KMS18 and MM.1s in the presence or absence of IL-6 to determine whether IL-6 altered the pattern of Bim binding. Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 were immunoprecipitated from control cells or after 24 hours with IL-6, and the Bim associated with each antiapoptotic was quantitated by western blot. In both cell lines, the proportion of Bim bound to Mcl-1 increased at the expense of Bcl-2 associated Bim (Figure 3F). Therefore, in addition to decreasing Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence, IL-6 simultaneously increases Mcl-1 dependence by altering Bim priming, decreasing the amount of Bim available to be released from Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL while increasing the proportion bound to Mcl-1. Importantly, in MM.1s the change in Bim priming occurred without changes in the amount of coprecipitating Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, or Bcl-2, suggesting that the change in Bim binding is because of posttranslational modification.

IL-6 induces Mcl-1 dependence in the absence of increased Mcl-1 expression in KMS18

Although our data in 4 of 5 cell lines suggest that the changes in Bim binding and Mcl-1 dependence with IL-6 are not mediated by changes in Mcl-1 expression, this cannot be ruled out in KMS18, where a significant increase in Mcl-1 is observed following IL-6 treatment. Because the change in Mcl-1 expression occurs at both the mRNA and protein level we examined the role of STAT3 in IL-6–induced changes in KMS18 using siRNA silencing. Consistent with a role for STAT3-mediated transcription, silencing blocked the upregulation of Mcl-1 mRNA (Figure 4A) and protein (Figure 4B), but only partially reversed IL-6 induced protection from ABT-737 (Figure 4C), suggesting that in KMS18 IL-6 stimulation results in transcription independent events such as posttranslational modification that contribute to Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence. Efficient STAT3 knockdown was confirmed by western blot (Figure 4B) and transcription of SOCS3 (Figure 4A). STAT3 silencing had no effect in MM.1s suggesting a transcription independent mechanism in these cells (supplemental Figure 5). STAT3 silencing also had no effect on the basal levels of Mcl-1 and did not result in any cell death on its own, suggesting that STAT3 may be responsible only for IL-6–induced upregulation of Mcl-1 in KMS18.

STAT3 knockdown partially reverses the protective effect of IL-6. RNA (A) and protein lysates (B) were prepared from cells 72 hours after nucleoporation with either control siRNA or STAT3 siRNA and after 24 hours IL-6 treatment. RNA expression of Mcl-1 and SOCS3 was determined by qRT-PCR and is graphed as fold change relative to untreated control siRNA cells. Protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting for phospho-STAT3, total STAT3, Mcl-1, and actin. (C) Forty-eight hours after siRNA nucleoporation, cells were treated with 1.5 μM of ABT-737 with or without 1 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours and cell death measured by annexin V-FITC and PI staining. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (**P < .01; ****P < .0001).

STAT3 knockdown partially reverses the protective effect of IL-6. RNA (A) and protein lysates (B) were prepared from cells 72 hours after nucleoporation with either control siRNA or STAT3 siRNA and after 24 hours IL-6 treatment. RNA expression of Mcl-1 and SOCS3 was determined by qRT-PCR and is graphed as fold change relative to untreated control siRNA cells. Protein was subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting for phospho-STAT3, total STAT3, Mcl-1, and actin. (C) Forty-eight hours after siRNA nucleoporation, cells were treated with 1.5 μM of ABT-737 with or without 1 ng/mL IL-6 for 24 hours and cell death measured by annexin V-FITC and PI staining. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (**P < .01; ****P < .0001).

Inhibition of pathways downstream of IL-6 reverses its protective effect

Having determined that IL-6 induces Mcl-1 dependence through both transcriptionally dependent and independent mechanisms, we then examined the contribution of the signaling pathways activated by IL-6. Binding of IL-6 to its receptor activates the JAK/STAT, Ras/MAPK, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways.14 We treated KMS18 and MM.1s with inhibitors of JAK (AZD1480, ruxolitinib), MEK (U0126), and PI3K (LY294002) and measured apoptosis in the presence of ABT-737 and IL-6. Not surprisingly, JAK inhibition completely reversed the protective effect of IL-6, most likely by blocking the initial activation event and therefore all downstream pathways (Figure 5A). The MEK inhibitor was as effective as JAK inhibition in MM.1s, suggesting that the Ras/MAPK pathway is vital to rescuing these cells from ABT-737. However, in KMS18, MEK inhibition only restored ∼50% of the apoptosis induced by ABT-737. The discrepancy between these 2 lines may reflect underlying differences in the biology of the cell lines. Of note, neither ruxolitinib, U0126, nor LY294002 induced any cell death when given alone, but U0126 did sensitize both cell lines to ABT-737 such that we observed increased apoptosis with the combination compared with ABT-737 alone. In fact MEK inhibition increased the sensitivity of OPM2 and U266 to ABT-737, although overall they remained resistant when compared with KMS18 and MM.1s (supplemental Figure 6). Moreover, MEK inhibition also increased the sensitivity of all 4 cell lines to the Bcl-2 specific inhibitor ABT-199 (supplemental Figure 6). These results would suggest that MEK inhibition can enhance Bcl-2 dependence in myeloma even in the absence of IL-6. PI3K inhibition had minimal effect on IL-6–mediated protection. We confirmed the effectiveness of these inhibitors by phospho-western blot (supplemental Figure 7).

Distinct effects of IL-6 signaling pathways on Bim and Mcl-1. (A) MM.1s and KMS18 were treated with ABT-737 in combination with 1 ng/mL IL-6 and either 1 μM ruxolitinib, 10 μM U0126, or 10 μM LY294002 for 24 hours. Cell death was measured by flow cytometry after staining with annexin V-FITC and PI. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001). (B) MM.1s was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 in the presence of 1 μM AZD1480, 10 μM LY294002, 10 μM SB203580, 10 μM SP600125, or 10 μM U0126 for 15 minutes. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting with antibodies against serine 69 phosphorylated Bim, total Bim, phosphorylated Erk, and total Erk. (C) KMS18 was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 for the indicated times and with 10 μM U0126 followed by western blotting for Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, serine 69 phosphorylated Bim, total Bim, and actin. (D) KMS18 was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 with or without 1 μM ruxolitinb for 24 hours followed by western blotting for Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and GAPDH.

Distinct effects of IL-6 signaling pathways on Bim and Mcl-1. (A) MM.1s and KMS18 were treated with ABT-737 in combination with 1 ng/mL IL-6 and either 1 μM ruxolitinib, 10 μM U0126, or 10 μM LY294002 for 24 hours. Cell death was measured by flow cytometry after staining with annexin V-FITC and PI. Data are presented as the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001). (B) MM.1s was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 in the presence of 1 μM AZD1480, 10 μM LY294002, 10 μM SB203580, 10 μM SP600125, or 10 μM U0126 for 15 minutes. Protein lysates were prepared and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting with antibodies against serine 69 phosphorylated Bim, total Bim, phosphorylated Erk, and total Erk. (C) KMS18 was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 for the indicated times and with 10 μM U0126 followed by western blotting for Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, serine 69 phosphorylated Bim, total Bim, and actin. (D) KMS18 was treated with 1 ng/mL IL-6 with or without 1 μM ruxolitinb for 24 hours followed by western blotting for Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and GAPDH.

We also examined the effects of IL-6 and signaling inhibitors on Bcl-2 family members. We used a modification of the standard SDS-PAGE system known as PhosTag, which allows identification of phosphorylated proteins without phospho-specific antibodies.32 Interestingly, in MM.1s a large fraction of Bim is constitutively phosphorylated. IL-6 induces additional phosphorylation of Bim but has no effect on Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 (supplemental Figure 8A). Bim is known to be phosphorylated by Erk1/2.33-35 Phosphorylation of serine 69 and serine 77 were detected in both MM.1s and KMS18 upon IL-6 treatment and could be inhibited with U0126 as well as AZD1480 (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figures 7 and 8B). As expected for a target of Erk kinase activity, phosphorylation of Bim correlated with phosphorylation of Erk. IL-6–induced upregulation of Mcl-1 in KMS18 was not blocked by U0126 but was blocked by ruxolitinib (Figure 5C-D). Treatment with IGF-1 potently induced phospho-Akt but had no effect on Bim serine 69 or Erk phosphorylation, consistent with its limited ability to prevent ABT-737–induced apoptosis, and further suggesting that the PI3K/Akt pathway has no impact on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence (supplemental Figure 9). Together these data suggest that IL-6 controls Bim binding in part through an MEK-dependent mechanism that is independent of changes in Mcl-1 expression.

MEK inhibition results in increased Bim binding to Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL

The factors responsible for determining which antiapoptotic Bim binds to have yet to be identified. After observing both a shift in Bim binding to Mcl-1 and Bim phosphorylation with IL-6 stimulation, we hypothesized that the 2 processes may be related. We therefore performed Bim coimmunoprecipitation with both IL-6 and U0126. In 4 cell lines (KMS18, MM.1s, KMS12BM, and OCI-My5) U0126 increased the amount of Bcl-2 bound to Bim (Figure 6). Interestingly, this occurred with and without IL-6 stimulation, possibly because of low levels of constitutive Ras signaling, either a result of FGFR3 activation in KMS18, the activating Ras mutation in MM.1s, or signals from growth factors present in the culture media. Consistent with this possibility, we routinely observe small background amounts of serine 69 phosphorylated Bim by western in the absence of IL-6 stimulation. In addition to the change in the Bim binding pattern, we also detected an increase in the total amount of Bim coprecipitating with the antiapoptotics. This increase occurred despite similar amounts of Bim in the whole cell lysate. The increased Bim and its binding to Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL may account for the enhanced cell death seen with ABT-737 in the presence of U0126. We subjected the same lysates of KMS18 and MM1.s to coimmunoprecipitation of Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2 and found similar results (supplemental Figure 10). As expected, IL-6 increased the amount of Bim associated with Mcl-1 whereas U0126 increased the amount of Bim coprecipitating with Bcl-2.

MEK inhibition increases Bcl-2 dependence. (A) KMS18, (B) MM.1s, (C) KMS12BM, and (D) OCI-My5 were treated with 1 ng/ml IL-6 and/or 10 μM U0126 for 24 hours, and protein lysates were prepared and then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Bim antibodies. The resulting protein complexes and protein input (WCL) were examined by western blot analysis using anti-Bim, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-Bcl-2, and anti-actin. The amount of coprecipitated protein was quantitated by densitometry and normalized to control. Figures are representative of 2 to 3 independent experiments.

MEK inhibition increases Bcl-2 dependence. (A) KMS18, (B) MM.1s, (C) KMS12BM, and (D) OCI-My5 were treated with 1 ng/ml IL-6 and/or 10 μM U0126 for 24 hours, and protein lysates were prepared and then subjected to coimmunoprecipitation with anti-Bim antibodies. The resulting protein complexes and protein input (WCL) were examined by western blot analysis using anti-Bim, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-Bcl-2, and anti-actin. The amount of coprecipitated protein was quantitated by densitometry and normalized to control. Figures are representative of 2 to 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

Although myeloma is typically thought of as Mcl-1 dependent, and potent Mcl-1 inhibitors such as S63845 are likely to be very effective in this disease,8 a distinct subset of myeloma may be primarily Bcl-2 dependent and potentially resistant to Mcl-1 inhibitors. A number of studies have described the Bcl-2 dependence of myeloma characterized by the t(11;14) translocation.9-13 These results are supported by an ongoing phase 1 trial of venetoclax in multiple myeloma that has reported an objective response rate of 40% among patients with t(11;14).36 However, given that 60% of t(11;14) patients failed to respond to venetoclax, the presence of t(11;14) is clearly not sufficient to dictate Bcl-2 dependence. In addition, cyclin D1 has not been reported to affect Bcl-2 family expression or Bim phosphorylation. These observations suggest that although t(11;14) is associated with venetoclax sensitivity, it may not play a direct role in Bcl-2 dependence. Given the uncertainty surrounding factors regulating Bcl-2 dependence in multiple myeloma, we investigated the effects of bone marrow stroma and IL-6 on this process and have demonstrated that IL-6 regulates Bcl-2 family dependence. More importantly, our data provide a scientific rationale for combining IL-6 signaling inhibitors with Bcl-2 inhibitors in multiple myeloma.

Stroma and stroma-derived cytokines have been previously demonstrated to influence Bcl-2 family dependence in other cell types. In chronic lymphocytic leukemia, costimulation with CD154 and IL-4 resulted in increased resistance to ABT-737 through increased expression of Bcl-xL, BCL2A1, and NOXA, although Bim binding to the antiapoptotics was unchanged.37 Neither CD154 nor IL-4 induce MEK activation, which may account for the absence of change in Bim binding. Alternatively, specific cytokine and cell type interactions may regulate Bcl-2 family dependence through different mechanisms.

Plasma cells are supported by BMSC secretion of crucial cytokines such as IL-6, IGF-1, and vascular endothelial growth factor, as well as adhesion-related signals. Of these cytokines, IL-6 is likely to play a dominant role.38 Indeed, exogenous IL-6, but not IGF-1, was able to recapitulate the increased Mcl-1 dependence induced by stromal cells and conditioned media while an IL-6 neutralizing antibody restored Bcl-2/Bcl-xL dependence in cell line experiments. However, in experiments with freshly isolated myeloma patient cells, exogenous IL-6 was not as effective as stromal cells, and IL-6 neutralizing antibody did not completely restore the ABT-737–induced apoptosis in the presence of stroma. These results may have been because of an inability to fully block IL-6. In experiments with MM.1s, we observed additive effects of combined IL-6 neutralization and IL-6 receptor blockade with 50% conditioned media and Hs-5 cells. Alternatively, IL-6 may not be the sole factor regulating Bcl-2 family dependence and a signal from direct cell–cell contact between plasma cells and stromal cells may be contributing as well. Integrin mediated signals, CD28/CD80/CD86, and BAFF/B cell maturation antigen also promote plasma cell survival.14-16,39

Although IL-6 regulates transcription of some Bcl-2 family members, expression alone does not account for sensitivity to Bcl-2 inhibitors. We therefore examined posttranslational modifications of Bim and its effects on binding to Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-2. ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Bim has been reported to result in proteasomal degradation of Bim.33,34,40,41 However, we did not observe any significant reduction in Bim protein upon IL-6 stimulation. In our experiments, IL-6 stimulation and Bim phosphorylation did correlate with a redistribution of Bim from Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL to Mcl-1. MEK inhibition blocked Bim phosphorylation, increased association of Bim with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, and sensitized cells to ABT-737 and ABT-199. Together, these results indicate that posttranslational modifications may selectively affect the binding affinity of Bim to antiapoptotics, and thus Bcl-2 family dependence. ABT-737 and MEK inhibitors have been reported to act synergistically in other cell types, although through different mechanisms. MEK inhibitors enhance cell death with ABT-737 by reducing Mcl-1 expression and Bcl-2 phosphorylation in acute myeloid leukemia,42,43 while in B-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, MEK inhibition results in increased binding of Bim to both Bcl-xL and Mcl-1.44 Treatment of KRAS or BRAF mutant cells derived from solid tumors with an MEK inhibitor also increased Bim levels and binding to Bcl-xL as well as Mcl-1 and synergized with ABT-737 or navitoclax, suggesting this may be a common mechanism of evading apoptosis.45,46 Similar activating Ras and Raf mutations are common in myeloma and could result in increased Bim phosphorylation and Mcl-1 dependence as we have demonstrated here.

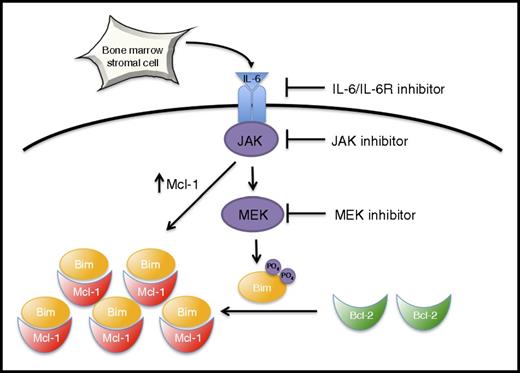

The insight into IL-6–mediated regulation of the Bcl-2 family in multiple myeloma provided by our data has a number of clinical implications. In light of the early clinical results with venetoclax in myeloma, the relationship between Bcl-2 dependence and the bone marrow microenvironment is very heterogeneous. Patients who achieved a sustained complete response with single agent venetoclax must be highly Bcl-2 dependent despite signals from the microenvironment. However, these patients represent only a small fraction of the overall population, and the majority of patients, including many with t(11;14), are likely to be either partially Bcl-2 dependent or Mcl-1 dependent. In this group of patients, IL-6 signaling may play an important role in regulating Bcl-2 family dependence. We have demonstrated that signaling from bone marrow microenvironment–derived IL-6 and the Ras/MAPK pathway induce Mcl-1 dependence while simultaneously decreasing dependence on Bcl-2/Bcl-xL in multiple myeloma through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms (Figure 7), representing a potential source of resistance to Bcl-2 inhibitors. Although responses in myeloma to the IL-6 inhibitor siltuximab as a single agent have been limited,47 IL-6 inhibition may have had an unappreciated effect on cells resulting in increased Bcl-2 dependence, both by decreasing Mcl-1 expression and shifting binding of Bim to Bcl-2. Similarly, some of the responses seen in early studies of the MEK inhibitor trametinib in myeloma patients both with and without activating Ras pathway mutations may be related to inhibition of IL-6–mediated Bim phosphorylation.48 By enhancing Bcl-2 dependence in myeloma, inhibitors of IL-6 signaling such as anti-IL-6 or IL-6R antibodies, JAK inhibitors, or MEK inhibitors may act synergistically with venetoclax and therefore warrant additional study in combination trials.

Model of stroma-induced Mcl-1 dependence. See “Discussion” for details.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who agreed to donate research specimens for this study.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (R01 CA192844 and 5 P30CA138292). L.H.B. is supported by the TJ Martell Foundation and is a Georgia Research Alliance Cancer Scholar.

Authorship

Contribution: V.A.G., S.M.M., and L.H.B. participated in conceptualization; V.A.G., S.M.M., and J.E.C.-P. designed and performed experiments; A.K.N., J.L.K., and S.L. provided patient samples; V.A.G. prepared the manuscript; S.M.M., J.E.C.-P., A.K.N., J.L.K., S.L., and L.H.B. assisted with review and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lawrence H. Boise, Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Emory University School of Medicine, 1365 Clifton Rd NE, Room C4012, Atlanta, GA 30322; e-mail: lboise@emory.edu.