In this issue of Blood, Sbihi et al provide the first evidence of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cell abnormalities in patients with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) –associated multicentric Castleman disease (MCD).1

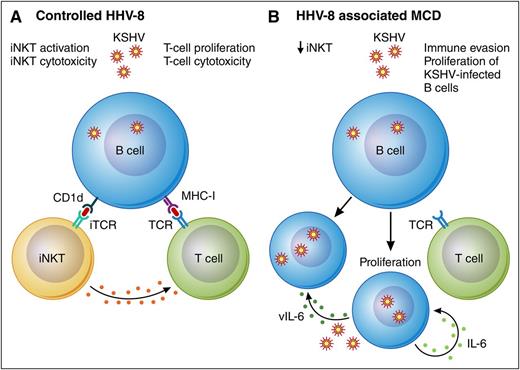

Model of HHV-8–associated MCD associated with diminished iNKT cells. (A) Controlled HHV-8 infection of B cells is associated with limited lytic activation of HHV-8 and effective immune surveillance by T cells and iNKT cells. Activated iNKT cells likely produce cytokines that further promote antiviral immunity in this setting. (B) HHV-8–associated MCD is associated with decreased iNKT cells. In addition, dysregulated lytic activation of HHV-8 leads to upregulation of the HHV-8–encoded E3 ubiquitin ligases K3 and K5, which downregulate CD1d and MHC-I and further promote immune evasion. Upregulation of human and viral IL-6 and other cytokines in this setting promotes proliferation of HHV-8–infected B cells. iTCR, invariant T-cell receptor; TCR, T-cell receptor; vIL-6, viral IL-6. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Model of HHV-8–associated MCD associated with diminished iNKT cells. (A) Controlled HHV-8 infection of B cells is associated with limited lytic activation of HHV-8 and effective immune surveillance by T cells and iNKT cells. Activated iNKT cells likely produce cytokines that further promote antiviral immunity in this setting. (B) HHV-8–associated MCD is associated with decreased iNKT cells. In addition, dysregulated lytic activation of HHV-8 leads to upregulation of the HHV-8–encoded E3 ubiquitin ligases K3 and K5, which downregulate CD1d and MHC-I and further promote immune evasion. Upregulation of human and viral IL-6 and other cytokines in this setting promotes proliferation of HHV-8–infected B cells. iTCR, invariant T-cell receptor; TCR, T-cell receptor; vIL-6, viral IL-6. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

HHV-8, also known as Kaposi sarcoma (KS) herpesvirus (KSHV), is a γ-herpesvirus that can infect a variety of cells, including endothelial cells, B cells, and antigen-presenting cells. Like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the most closely related γ-herpesvirus, HHV-8 generally establishes latent infection in host cells. Important to the establishment of infection are HHV-8 codes for a variety of proteins that allow for immune evasion, including 2 ubiquitin E3 ligases, K3 and K5, that downregulate surface proteins that are important for immune surveillance such as MHC-I, ICAM, MICA, and CD1d.2,3 Although HHV-8 infection is generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent hosts, in the setting of immune disorders, HHV-8 can lead to 2 important proliferative disorders, KS and a plasmablastic form of MCD, HHV-8–associated MCD. HHV-8 is also the etiologic agent of a rare form of aggressive B-cell lymphoma: primary effusion lymphoma. Both KS and HHV-8–associated MCD are strongly associated with HIV infection and iatrogenic immunosuppression and can also be seen with increased age, implicating acquired factors in host immunity in disease pathogenesis.

Interestingly, clinical and epidemiologic factors suggest that the immune abnormalities leading to each of these diseases may vary. KS manifests as tumors consisting of proliferation of HHV-8–infected spindle cells of endothelial origin, whereas HHV-8–associated MCD is a lymphoproliferative disorder driven by expansion of HHV-8–infected naïve B cells with plasmablastic morphology that leads to lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and human and viral interleukin-6 (IL-6)–related syndromes.4 These tumors vary in their expression of HHV-8–encoded oncogenes. In KS, the majority of tumor cells express only a limited repertoire of latent viral-encoded genes, whereas in HHV-8–associated MCD, a sizeable proportion of infected plasmablasts also express viral IL-6 and a number of lytic viral genes. In the setting of HIV, KS is strongly associated with CD4+ lymphocytopenia,5 defects in HHV-8–specific CD8+ cells have been demonstrated,6 and treatment with antiretroviral therapy has some preventive effect. In contrast, HHV-8–associated MCD generally occurs in the setting of relatively preserved CD4+ T-cell counts, HHV-8–specific effector CD8+ T cells are demonstrable,7 and incidence may actually be increasing because people coinfected with HIV and HHV-8 are living longer on antiretroviral therapy.8

The work by Sbihi et al provides important insights into the immunobiology of HHV-8–associated MCD and contributes to our understanding of these clinical observations. On the basis of evidence for a roll of iNKT in controlling EBV infections, the authors evaluated iNKT cell number and function in a well-characterized cohort of HHV-8–associated MCD patients with and without HIV. iNKT cells are a unique population of T cells with a highly restricted T-cell repertoire that recognize glycolipid antigens presented on the MHC-I–related molecule, CD1d. They play an important role in innate immunity and are essential for control of EBV-infected B cells. iNKT cells are reduced in people with HIV,9 and functional impairment of iNKT cells in HIV has been demonstrated and may persist despite antiretroviral therapy.

In a series of elegant flow analyses and in vitro experiments, the authors demonstrate that iNKT abnormalities are associated with HHV-8–associated MCD. Comparing both peripheral blood and spleen specimens from patients with HHV-8–associated MCD to both patients with KS (HIV infected and HIV uninfected) and healthy volunteers, the authors found that iNKT cells were decreased in patients with HHV-8–associated MCD, regardless of HIV status, compared with either control group (see figure). Furthermore, iNKT cells from HHV-8–associated MCD patients demonstrated an intrinsic defect in the ability to proliferate in vitro after stimulation with α-galactosylceramide. The investigators also found a decrease in circulating and splenic memory B cells in these same patients. Coculturing experiments suggested that iNKT cells may be required for maintaining this cell population.

Results from the Sbihi et al study provide the strongest association to date for a specific cellular immune defect in HHV-8–associated MCD and are an important contribution to the field. This study has implications for potential immunotherapeutic approaches to HHV-8–associated MCD. Current therapy consists of the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab, alone or in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy.10 Although this approach has dramatically improved survival in patients with HHV-8–associated MCD, rituximab can lead to worsening of KS or infectious complications. For these reasons, a more targeted immune modulatory approach may be desirable. The work of Sbihi et al provides a rationale for iNKT-directed interventions in HHV-8–associated MCD. Inhibition of HHV-8 downregulation of CD1d and/or augmentation of iNKT cell number or function could, in theory, improve immune surveillance of HHV-8–infected B cells and could be useful in the treatment of HHV-8–associated MCD. Further evaluation of such approaches is warranted.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.S.U. is named as a federal employee on a provisional patent application for immunomodulatory compounds for KSHV-associated malignancies.