Key Points

The extant vertebrate hagfish, M glutinosa, has a single, functional vwf gene, structurally simpler than in higher vertebrates.

VWF appeared in an ancestral vertebrate as a hemostatic protein lacking functional domains required for primary hemostasis under high flow.

Abstract

Hemostasis in vertebrates involves both a cellular and a protein component. Previous studies in jawless vertebrates (cyclostomes) suggest that the protein response, which involves thrombin-catalyzed conversion of a soluble plasma protein, fibrinogen, into a polymeric fibrin clot, is conserved in all vertebrates. However, similar data are lacking for the cellular response, which in gnathostomes is regulated by von Willebrand factor (VWF), a glycoprotein that mediates the adhesion of platelets to the subendothelial matrix of injured blood vessels. To gain evolutionary insights into the cellular phase of coagulation, we asked whether a functional vwf gene is present in the Atlantic hagfish, Myxine glutinosa. We found a single vwf transcript that encodes a simpler protein compared with higher vertebrates, the most striking difference being the absence of an A3 domain, which otherwise binds collagen under high-flow conditions. Immunohistochemical analyses of hagfish tissues and blood revealed Vwf expression in endothelial cells and thrombocytes. Electron microscopic studies of hagfish tissues demonstrated the presence of Weibel-Palade bodies in the endothelium. Hagfish Vwf formed high-molecular-weight multimers in hagfish plasma and in stably transfected CHO cells. In functional assays, botrocetin promoted VWF-dependent thrombocyte aggregation. A search for vwf sequences in the genome of sea squirts, the closest invertebrate relatives of hagfish, failed to reveal evidence of an intact vwf gene. Together, our findings suggest that VWF evolved in the ancestral vertebrate following the divergence of the urochordates some 500 million years ago and that it acquired increasing complexity though sequential insertion of functional modules.

Introduction

von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a large multimeric glycoprotein expressed in endothelial cells and megakaryocytes/platelets (reviewed in Denis, Ruggeri, Sadler, and Haberichter and Montgomery1-4 ). VWF mediates the adhesion and aggregation of platelets at sites of vascular injury (reviewed in Lenting et al, Mendolicchio and Ruggeri, and Reininger5-7 ). Normally, globular VWF binds collagen in the subendothelial matrix following vascular injury. Collagen binding, together with shear stress, enables VWF to assume an extended conformation, resulting in exposure of its A1 domain, which can then interact with GPIbα on the surface of platelets. In addition, VWF binds and transports coagulation factor VIII (FVIII), thereby protecting FVIII from rapid clearance and increasing its half-life.8-10 Deficient or defective VWF results in von Willebrand disease (VWD), a common inherited bleeding disorder, whereas overactive VWF has been implicated in several thrombotic disorders, including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.11

In humans, VWF is synthesized as a precursor protein of 2813 amino acids with a cleavable 22-amino-acid signal peptide, a large 741-amino-acid propolypeptide (VWF antigen II), and a mature multidomain subunit of 2050 amino acids (Figure 1A) (reviewed in Lenting et al12 ). After removal of the signal peptide, the 307-kDa monomer (pro-VWF) undergoes posttranslational modification with the addition of up to 22 carbohydrate chains, and assembles in the endoplasmic reticulum into dimers through disulfide bonds between C-terminal cystine knot (CTCK) domains (at VWF Cys2771, Cys2773, and Cys2811).13 Pro-VWF dimers are then transported to the Golgi, where furin-mediated cleavage of the propeptide occurs after the D1-D2 domains. The remaining N-terminal D3 domain undergoes additional head-to-head interdisulfide bonding at Cys1142 and Cys1099, leading to multimerization of VWF.14 The number of subunits in each multimer varies, with molecular weights ranging from 500 000 (mature VWF dimer) to >20 million Daltons.

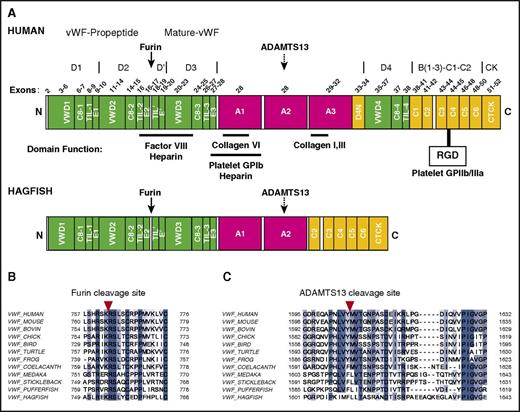

Domain structure of human and hagfish VWF. (A) Schematic representation of the overall domain structure of human and hagfish VWF based on recently revised domain assignments.28 Shown are annotations of the furin cleavage site (solid arrow), the heparin, FVIII, GPIbα, and collagen binding sites, the RGD recognition site for GPIIb/IIIa, the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (dashed arrow), and known human exons. Note that hagfish Vwf lacks the A3 domain and the large adjacent multidomain region, D4N-VWD4-C8-4-TIL-4-C1.C, C-terminal end; N, N-terminal end. (B) Amino acid alignments of VWF sequences from varied vertebrate species at the furin cleavage site (red arrowhead). (C) Amino acid alignments of VWF sequences from varied vertebrate species at the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (red arrowhead). ADAMTS13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp.

Domain structure of human and hagfish VWF. (A) Schematic representation of the overall domain structure of human and hagfish VWF based on recently revised domain assignments.28 Shown are annotations of the furin cleavage site (solid arrow), the heparin, FVIII, GPIbα, and collagen binding sites, the RGD recognition site for GPIIb/IIIa, the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (dashed arrow), and known human exons. Note that hagfish Vwf lacks the A3 domain and the large adjacent multidomain region, D4N-VWD4-C8-4-TIL-4-C1.C, C-terminal end; N, N-terminal end. (B) Amino acid alignments of VWF sequences from varied vertebrate species at the furin cleavage site (red arrowhead). (C) Amino acid alignments of VWF sequences from varied vertebrate species at the ADAMTS13 cleavage site (red arrowhead). ADAMTS13, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 13; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp.

Megakaryocyte-derived VWF is stored in platelet α-granules.15 In endothelial cells, VWF directs the formation of its own releasable storage granule, the Weibel-Palade body (WPB),16 through a multistep process that generates and packages highly active, high-molecular-weight VWF multimers in a helicoid structure or tubule (reviewed in Nightingale and Cutler, Sadler, and Valentijn et al17-19 ). Once released, WPB-derived ultralarge VWF multimers are rapidly cleaved in the presence of shear stress by metalloproteinase ADAMTS13 (reviewed in Sander et al20 ).

Several functions of VWF have been mapped to specific domains (Figure 1A) (reviewed in Lenting et al12 ). The A1 domain binds the platelet receptor glycoprotein GPIbα. The A3 domain binds fibrillar collagen types I and III of the deeper layers of the vessel wall, whereas the A1 domain binds nonfibrillar (microfibrillar) collagen types IV and VI of the subendothelial matrix.21-27 The D'-D3 domains (reassigned in Zhou et al28 to TIL'-E'-VWD3-C8-3-TIL-3-E3) bind FVIII, heparin, and snake toxins botrocetin and bitiscetin. The D4 region acts as part of the ADAMTS13 docking sequence to optimize cleavage of the A2 domain.29,30 The C1 domain (reassigned to C4) contains an RGD sequence that mediates platelet receptor glycoprotein GPIIb/IIIa binding. The site for ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis lies within the A2 domain.

In vertebrates, blood clotting involves both cells (thrombocytes in nonmammalian vertebrates; platelets in mammals) and a highly conserved network of protease reactions for the thrombin-catalyzed conversion of the soluble plasma protein, fibrinogen, into an insoluble, polymeric fibrin clot. All vertebrates studied to date, including lamprey (a jawless fish), are capable of generating fibrin clots.31 Previous studies demonstrated that zebrafish possess the extrinsic arm of the clotting cascade, in addition to factor IX in the intrinsic limb.32 In contrast, the lamprey is reported to lack an intrinsic pathway.33 With respect to primary (cell-based) hemostasis, full-length vwf complementary DNA (cDNA) has been identified in bony fish, including pufferfish34 and zebrafish.35 However, evidence for the presence of Vwf in jawless fish is lacking. Here, we report the cloning of full-length vwf cDNA from the Atlantic hagfish, Myxine glutinosa. Our results suggest that VWF first arose as a hemostatic protein that, although capable of multimerizing, lacked functional domains that are required to mediate primary hemostasis under high-flow conditions.

Methods

Atlantic hagfish, M glutinosa, were collected in the Gulf of Maine 10 miles east of the Isle of Shoals, New Hampshire. They were transported to the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Salisbury Cove, Maine and kept in the dark, in flow-through seawater (∼17°C) tanks for 20 to 40 days before being euthanized. In all terminal procedures, hagfish were anesthetized in seawater containing tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222; 1:2500 wt/vol) prior to decapitation. Experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. The supplemental Materials and methods, available on the Blood Web site, include the isolation of the hagfish vwf gene, the stable transfection of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, the generation of antibodies against hagfish Vwf, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays, histochemistry and immunohistochemistry, western blots, agarose gel plasma VWF multimer analysis, optical platelet aggregation studies, ADAMTS13 cleavage of CHO cell-expressed hagfish VWF, electron microscopy, protein sequence analysis, homology protein structure modeling, and A2 model structure tensile force–induced unfolding simulations.

Results

Cloning and characterization of hagfish vwf cDNA

To clone full-length vwf cDNA from hagfish, we used PCR with degenerate primers (supplemental Table 1) designed from conserved amino acid regions within multiple vertebrate VWF sequence alignments, followed by rapid amplification of cDNA ends using gene-specific and nested primer sets (supplemental Table 1). The 6513-bp open reading frame encodes a putative protein of 2170 amino acids (237.5 kDa). Processing of a putative N-terminal 15-amino-acid signal sequence would result in a predicted protein (pro-Vwf) of 2155 amino acids (235.9 kDa). Further processing to remove the 740-amino-acid propeptide sequence would result in a mature protein (mature-Vwf) of 1415 amino acids (155.2 kDa). Hagfish pro-Vwf is 636 amino acids shorter than human with 31.5% overall sequence homology (supplemental Table 2). Alignments of hagfish Vwf to VWF sequences from multiple vertebrates, ranging from pufferfish to humans (supplemental Figure 1-2A-E; supplemental Table 3), identify the conservation of specific domains in hagfish Vwf and the absence of other domains that are otherwise conserved in higher vertebrates. Based on recently revised domain annotations of VWF,28 hagfish Vwf contains VWD1-C8-1-TIL-1-E1, VWD2-C8-2-TIL-2-E2, TIL'-E', VWD3-C8-3-TIL-3-E3, A1, A2, C2-C6, and CTCK (Figure 1A). The FVIII binding region, the GPIbα binding region, and the GPIIb/IIIa binding region are each intact. Interestingly, hagfish Vwf is missing A3, D4N, VWD4-C8-4-TIL-4, and C1. In mammals, the function of the C-terminal C1-C6 domains remains poorly understood. However, the absence of A3 suggests that hagfish Vwf does not bind to collagen types I and III, whereas the lack of a D4 domain raises the possibility that ADAMTS13-Vwf docking does not occur in hagfish.

Other key features of hagfish Vwf are identifiable with varying degrees of conservation. The furin propeptide cleavage site Rx(R/K)R is highly conserved in all species examined (Figure 1B), and in hagfish, comprises the same extended SxRxKRSLxC sequence as in human,36 suggesting that the propeptide of hagfish Vwf is cleaved by furin. The putative site for Vwf-cleaving protease ADAMTS13 in the A2 domain, based on sequence alignment, comprises an F-L residue pair. Although this differs from the highly conserved Y-M cleavage sequence observed in amphibians, birds, reptiles, and mammals (Figure 1C), it is consistent with the F-L pair observed in virtually all fish studied to date (except coelacanth, a fish more closely related to lobe-finned fish and tetrapods than common ray-finned fishes, which has an F-M residue pair). Finally, the CTCK cysteine residues involved in dimerization of pro-VWF (VWF Cys2771, Cys 2773, and Cys2811) and the D3 domain cysteine residues (Cys1142 and Cys1099) required for head-to-head interdisulfide bonding and multimerization of VWF are highly conserved (supplemental Figure 2B,E).

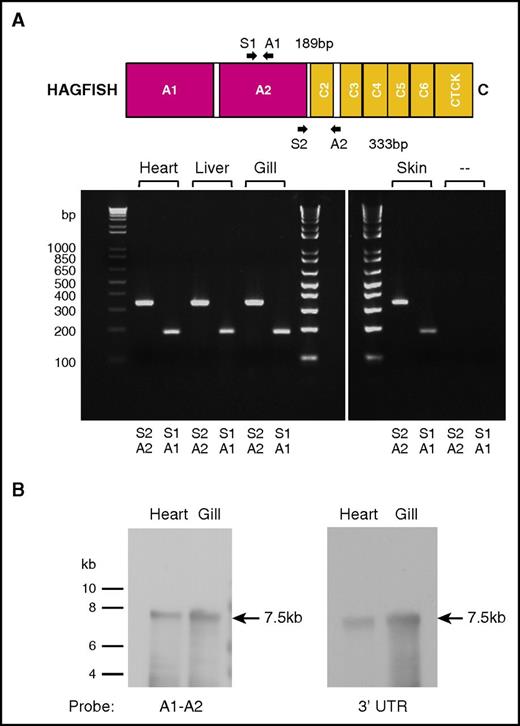

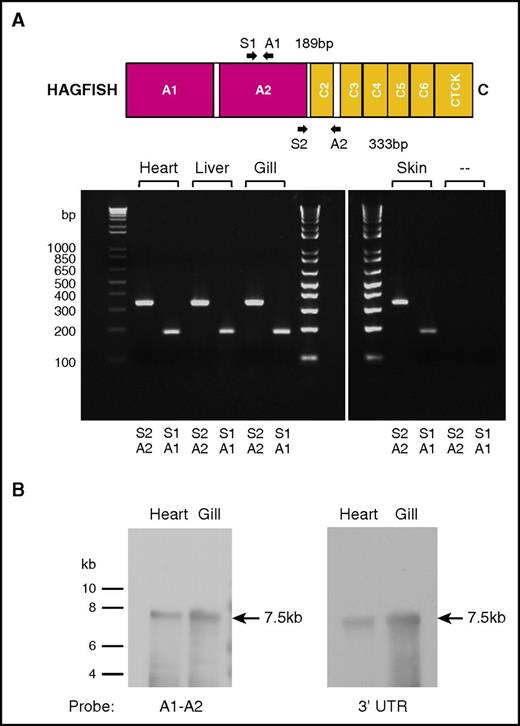

Hagfish vwf is expressed as a single gene product

To determine if the cloned vwf cDNA represents the only expressed vwf mRNA transcript in hagfish, we first carried out low-temperature annealing PCR using primers complementary to a region within the A2 domain region or an A2 through C2-C3 intervening loop region (supplemental Table 1). Analysis of PCR products amplified from hagfish heart, liver, gill, and skin cDNA showed single products of the expected size for both primer pairs (Figure 2A). Next, we carried out Northern blot hybridization of hagfish RNA from heart and gill with probes spanning portions of the A1-A2 region or the 3′ untranslated region of hagfish vwf (primer pairs used in PCR to generate DNA probes given in supplemental Table 1). These experiments revealed a single 7.5-kb transcript in both heart and gill (Figure 2B). Together, these findings argue against the presence of a duplicate vwf gene (or pseudogene) in hagfish.

Hagfish vwf is expressed as a single gene product. (A) PCR primer pairs A1/S1 and A2/S2 (supplemental Table 1) were used to generate DNA products from the A2 domain or from a region of the A2 domain to the C2-C3 spacer from hagfish vwf cDNA prepared by reverse transcription from hagfish heart, liver, gill, and skin RNA. Only the expected 189-bp and 333-bp PCR products were observed on agarose gel analysis. (‐‐) Control reactions without template cDNA. (B) Northern blot hybridization of hagfish RNA from heart and gill with probes that spanned either the A1-A2 region or the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) from the hagfish vwf gene (supplemental Table 1). A single 7.5-kb transcript is observed in both heart and gill.

Hagfish vwf is expressed as a single gene product. (A) PCR primer pairs A1/S1 and A2/S2 (supplemental Table 1) were used to generate DNA products from the A2 domain or from a region of the A2 domain to the C2-C3 spacer from hagfish vwf cDNA prepared by reverse transcription from hagfish heart, liver, gill, and skin RNA. Only the expected 189-bp and 333-bp PCR products were observed on agarose gel analysis. (‐‐) Control reactions without template cDNA. (B) Northern blot hybridization of hagfish RNA from heart and gill with probes that spanned either the A1-A2 region or the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) from the hagfish vwf gene (supplemental Table 1). A single 7.5-kb transcript is observed in both heart and gill.

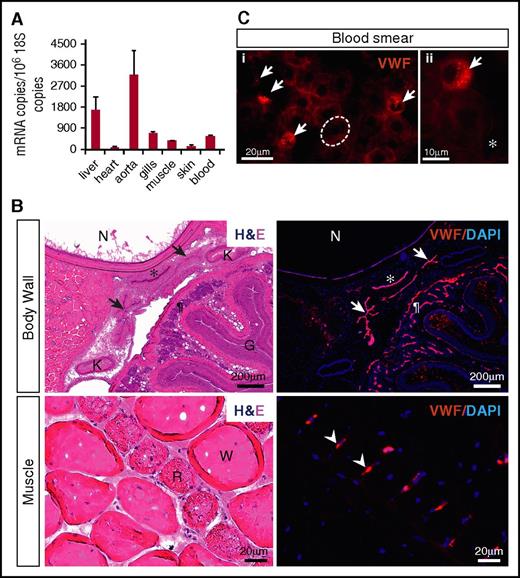

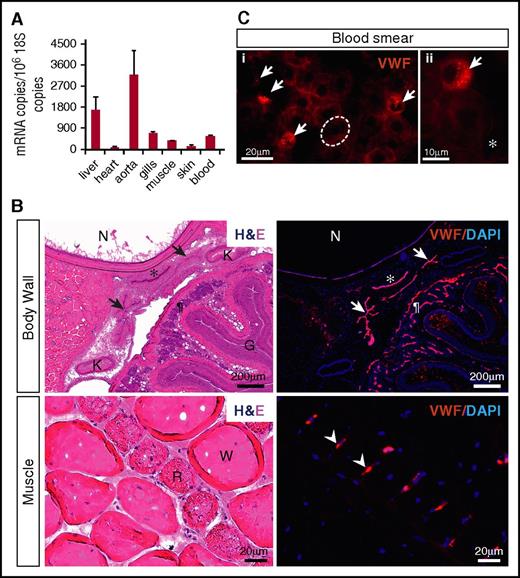

Hagfish Vwf is expressed in endothelium and peripheral blood

qPCR analysis of various hagfish tissues and whole blood revealed widespread expression of vwf mRNA, with highest transcript levels in the aorta and liver (Figure 3A). To localize Vwf expression, we carried out immunofluorescent studies. We began by testing the reactivity and specificity of a series of anti-human VWF antibodies. Remarkably, a human polyclonal antibody from Dako (A0082), which is reported to have cross-reactivity with several mammalian VWFs as well as that of chicken, revealed a positive signal in the endothelium of multiple hagfish organs (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 3A). To validate these results, we generated a mouse monoclonal anti-hagfish antibody (B10). Staining of tissue sections revealed a pattern identical to that observed with the Dako antibody (supplemental Figure 3B). In contrast to its mammalian counterpart, which is heterogeneously distributed across the vascular tree,37 hagfish Vwf was detected throughout all blood vessels examined.

Hagfish Vwf is expressed in endothelium and peripheral blood. (A) qPCR analysis of hemostatic factors in hagfish organs and blood. mRNA expression is represented as copy number per 106 18S copies. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3 fish). (B) Serial sections of the body wall and muscle of hagfish stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (left) and processed for immunofluorescence staining using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (right). Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Positive Vwf staining is observed in the aorta (*), posterior cardinal veins (arrows), capillaries of the intestinal wall (¶), and capillaries surrounding red muscle fibers (arrowheads). All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. G, gut lumen; K, kidney; N, notochord; R, red muscle fiber; W, white muscle fiber. (C) Fluorescence microscopy images of hagfish blood processed for immunofluorescence staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody. Left image (i) shows 4 Vwf-positive cells (arrows), which are smaller than neighboring Vwf-negative erythrocytes (1 of these is outlined in white). Right image (ii) is a higher-power view showing the punctate staining pattern of a Vwf-positive cell surrounded by Vwf-negative erythrocytes and spindle cells. All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. *Representative spindle cell. See supplemental Figure 4C-D for greater detail of negatively stained cells.

Hagfish Vwf is expressed in endothelium and peripheral blood. (A) qPCR analysis of hemostatic factors in hagfish organs and blood. mRNA expression is represented as copy number per 106 18S copies. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3 fish). (B) Serial sections of the body wall and muscle of hagfish stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (left) and processed for immunofluorescence staining using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (right). Nuclei are stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Positive Vwf staining is observed in the aorta (*), posterior cardinal veins (arrows), capillaries of the intestinal wall (¶), and capillaries surrounding red muscle fibers (arrowheads). All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. G, gut lumen; K, kidney; N, notochord; R, red muscle fiber; W, white muscle fiber. (C) Fluorescence microscopy images of hagfish blood processed for immunofluorescence staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody. Left image (i) shows 4 Vwf-positive cells (arrows), which are smaller than neighboring Vwf-negative erythrocytes (1 of these is outlined in white). Right image (ii) is a higher-power view showing the punctate staining pattern of a Vwf-positive cell surrounded by Vwf-negative erythrocytes and spindle cells. All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. *Representative spindle cell. See supplemental Figure 4C-D for greater detail of negatively stained cells.

In hagfish peripheral blood smears, immunofluorescence showed staining of Vwf in a subpopulation of nucleated blood cells (Figure 3C), whose morphology is consistent with thrombocytes as previously described by others (see supplemental Results and supplemental Figure 4 for description of hagfish blood cells).38 The staining demonstrated a punctate pattern, suggesting that Vwf may be stored in cytoplasmic granules. To confirm that hagfish thrombocytes do indeed possess granules, we carried out electron microscopy of peripheral blood. We identified a population of cells whose morphology is clearly distinct from that of erythrocytes and granulocytes and similar to that described for thrombocytes in fish.39 These cells contained a single type of granule throughout the cytoplasm (supplemental Figure 5). Together, our results suggest that expression of VWF in endothelial cells and platelets is evolutionarily conserved in all vertebrates.

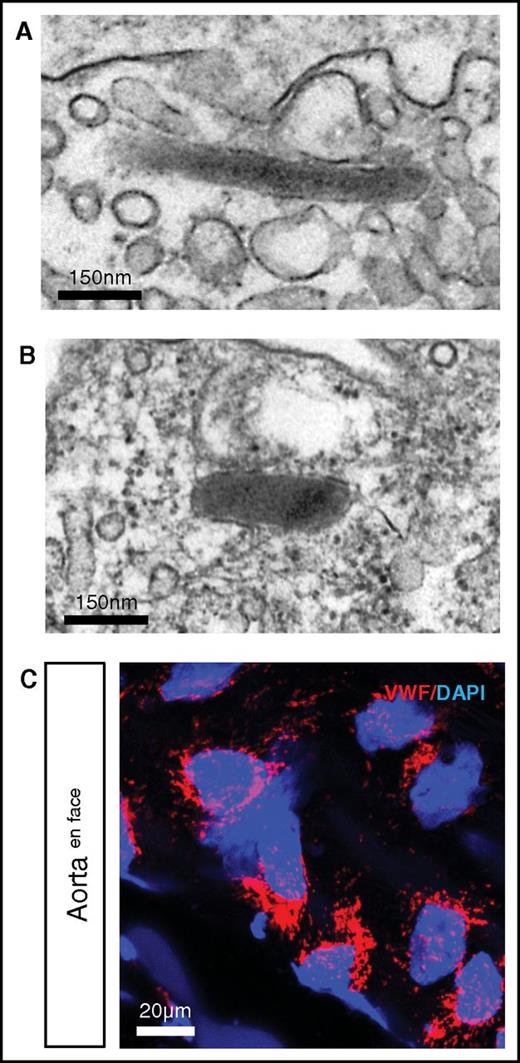

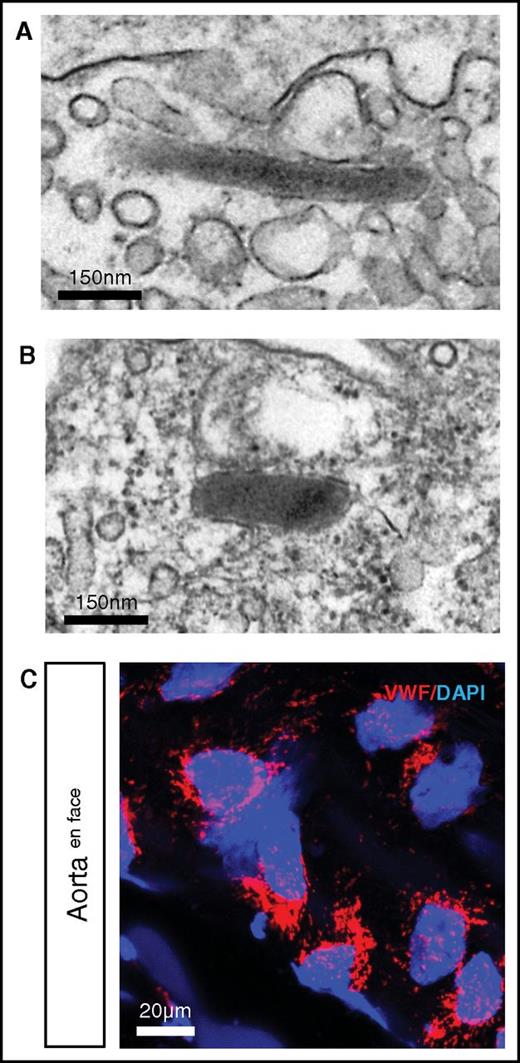

Hagfish Vwf is localized in endothelial WPBs

In higher vertebrates, VWF is stored in endothelial WPBs.19 We previously demonstrated that hagfish endothelial cells contain WPBs.40 Here, we carried out additional electron microscopic studies of hagfish tissues and confirmed the presence of WPBs in the intact endothelium (Figure 4A aorta; Figure 4B skeletal muscle arteriole). In en face preparations of the aorta, confocal immunofluorescence revealed punctate staining in all endothelial cells, consistent with localization of Vwf in WPBs (Figure 4C). Thus, storage of VWF in WPB appears to be an evolutionarily conserved feature of endothelial VWF processing.

Punctate Vwf staining and presence of WPBs in hagfish endothelial cells. Representative electron microscopy image of hagfish endothelium from aorta (A) and skeletal muscle arteriole (B) showing the presence of cigar-shaped organelles containing electron-dense tubules, consistent with WPBs. (C) Confocal laser scanning microscopy image of en face hagfish aorta processed for immunofluorescence staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (see supplemental Figure 3 for images using hagfish monoclonal Vwf antibody). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Note the presence of punctate staining in the endothelial cells. All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material.

Punctate Vwf staining and presence of WPBs in hagfish endothelial cells. Representative electron microscopy image of hagfish endothelium from aorta (A) and skeletal muscle arteriole (B) showing the presence of cigar-shaped organelles containing electron-dense tubules, consistent with WPBs. (C) Confocal laser scanning microscopy image of en face hagfish aorta processed for immunofluorescence staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (see supplemental Figure 3 for images using hagfish monoclonal Vwf antibody). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. Note the presence of punctate staining in the endothelial cells. All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material.

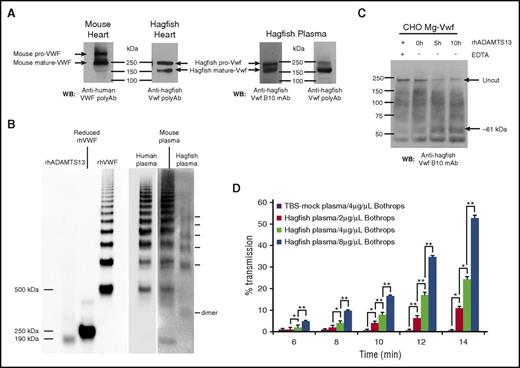

Hagfish Vwf propeptide undergoes posttranslational processing

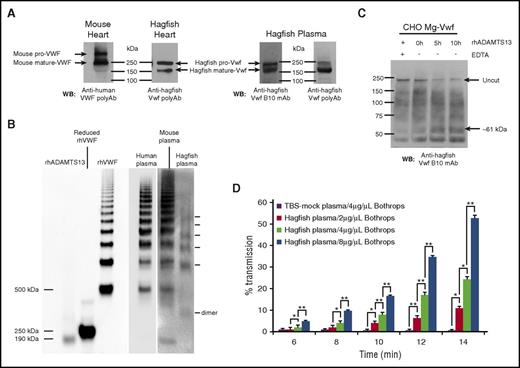

We next examined the expression and posttranslational processing of Vwf in hagfish heart lysates and plasma by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and western blot analysis with anti-Vwf antibody. Bands observed correlated with the expected size of unprocessed hagfish Vwf (pro-Vwf) at ∼240 kDa, as well as mature Vwf at ∼165 kDa (Figure 5A). Similar analyses using cell lysates from mouse heart showed unprocessed mouse VWF (pro-VWF) at ∼300 kDa and mature VWF at ∼250 kDa (Figure 5A). These results suggest conservation in the processing of mature VWF by posttranslational cleavage of the propeptide sequence.

Hagfish Vwf processing, plasma multimers, ADAMTS13 cleavage, and platelet aggregation. (A) Western blot (WB) of heart lysates from mouse or hagfish using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) or monoclonal anti-hagfish VWF antibody (B10), and of hagfish plasma using either monoclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody (B10) or polyclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody. Shown are bands whose sizes are consistent with mouse pro-VWF (∼300 kDa) and mature VWF (∼250 kDa), or hagfish pro-VWF (∼240 kDa) and mature VWF (∼165 kDa). (B) Human, mouse, and hagfish plasma proteins were separated on a nonreducing 1.5% agarose gel. Western blotting was carried out with polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) alongside molecular weight marking samples of reduced and nonreduced recombinant human VWF (rhVWF) and recombinant human ADAMTS13 (rhADAMTS13). (C) Samples of hagfish Vwf from expressing CHO-cell lysates in 1.5 M urea buffer were incubated for up to 10 hours with 70 nM of full-length recombinant human ADAMTS13 with (+) or without (−) 15 mM EDTA. Note the significant reduction of the ∼240-kDa pro-Vwf band in the presence of ADAMTS13 and the appearance of a C-terminal cleavage product (∼61 kDa) detected with monoclonal anti-hagfish B10 antibody raised against C-terminal Vwf sequence. (D) Thrombocyte-rich and thrombocyte-poor plasma was prepared from ∼12 hagfish animals and measured for thrombocyte aggregation as measured by light transmission over time. Thrombocytes resuspended in thrombocyte-poor plasma were equilibrated for 2 minutes at 37°C with stirring and then incubated with varying concentrations of botrocetin (B jararaca snake venom). Thrombocyte agglutination was monitored over time (reported as minutes following addition of botrocetin) using a dual-channel optical aggregometer. Data represent the mean and SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using paired Student t test (*P ≤ .5; **P ≤ .005). polyAB, polyclonal antibody; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; WB, western blot.

Hagfish Vwf processing, plasma multimers, ADAMTS13 cleavage, and platelet aggregation. (A) Western blot (WB) of heart lysates from mouse or hagfish using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) or monoclonal anti-hagfish VWF antibody (B10), and of hagfish plasma using either monoclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody (B10) or polyclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody. Shown are bands whose sizes are consistent with mouse pro-VWF (∼300 kDa) and mature VWF (∼250 kDa), or hagfish pro-VWF (∼240 kDa) and mature VWF (∼165 kDa). (B) Human, mouse, and hagfish plasma proteins were separated on a nonreducing 1.5% agarose gel. Western blotting was carried out with polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) alongside molecular weight marking samples of reduced and nonreduced recombinant human VWF (rhVWF) and recombinant human ADAMTS13 (rhADAMTS13). (C) Samples of hagfish Vwf from expressing CHO-cell lysates in 1.5 M urea buffer were incubated for up to 10 hours with 70 nM of full-length recombinant human ADAMTS13 with (+) or without (−) 15 mM EDTA. Note the significant reduction of the ∼240-kDa pro-Vwf band in the presence of ADAMTS13 and the appearance of a C-terminal cleavage product (∼61 kDa) detected with monoclonal anti-hagfish B10 antibody raised against C-terminal Vwf sequence. (D) Thrombocyte-rich and thrombocyte-poor plasma was prepared from ∼12 hagfish animals and measured for thrombocyte aggregation as measured by light transmission over time. Thrombocytes resuspended in thrombocyte-poor plasma were equilibrated for 2 minutes at 37°C with stirring and then incubated with varying concentrations of botrocetin (B jararaca snake venom). Thrombocyte agglutination was monitored over time (reported as minutes following addition of botrocetin) using a dual-channel optical aggregometer. Data represent the mean and SD from 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using paired Student t test (*P ≤ .5; **P ≤ .005). polyAB, polyclonal antibody; TBS, Tris-buffered saline; WB, western blot.

Hagfish Vwf forms mid-sized multimers in plasma

In mammals, VWF circulates in plasma as large, multimeric forms. To determine whether hagfish Vwf exhibits a similar pattern, we carried out nonreducing agarose gel analysis of plasma samples from hagfish, mice, and humans, followed by western blotting. In hagfish, the smallest band was ∼330 kDa, likely representing the dimerized form of Vwf (Figure 5B). Consistent with the abbreviated size of hagfish Vwf, this product was visibly smaller than the lowest-sized VWF multimers in human and mouse plasmas. Similar to its mouse and human counterparts, hagfish plasma demonstrated a ladder of Vwf multimers, although it lacked the higher-molecular-weight multimers (>7 bands) observed in human and mouse.

Hagfish Vwf is cleaved by human ADAMTS13

In mammals, ADAMTS13 cleaves the single bond between Y and M (human residues 1605 and 1606) located in the A2 domain.41 ADAMTS13 cleavage requires partial unfolding of the VWF multimer either naturally by shear stress or artificially by chemical denaturation.42 To determine whether ADAMTS13 cleaves hagfish Vwf, we chemically denatured hagfish Vwf from whole-cell lysates of stably transfected CHO cells (generation of these clones is discussed in more detail below) with 1.5 M urea and incubated it with full-length (aa 34-1427) recombinant human ADAMTS13. Cleavage was assessed on reducing SDS-PAGE gels and detected by western blotting. As shown in Figure 5C, addition of human ADAMTS13 in the absence but not presence of EDTA resulted in significant cleavage of hagfish Vwf concomitant with the appearance of a C-terminal cleavage product (∼61 kDa), strongly suggesting conservation of a functional cleavage site in hagfish Vwf.

Hagfish thrombocyte agglutination elicited by botrocetin

To test whether hagfish Vwf is functional, we employed optical aggregometry of hagfish thrombocytes. Ristocetin is typically used to test for human VWF-mediated platelet aggregation. However, ristocetin does not agglutinate mouse platelets,43,44 and in our studies, ristocetin failed to agglutinate hagfish thrombocytes (not shown). Botrocetin, a component of Bothrops jararaca venom, has been shown to induce platelet agglutination by a VWF-dependent mechanism that involves binding to GPIbα receptors on platelets.45 The addition of botrocetin resulted in a dose-dependent aggregation of hagfish thrombocytes in the presence but not absence of hagfish plasma (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 6). These findings suggest that hagfish Vwf binds to a GPIbα-like receptor on hagfish thrombocytes and is functionally active.

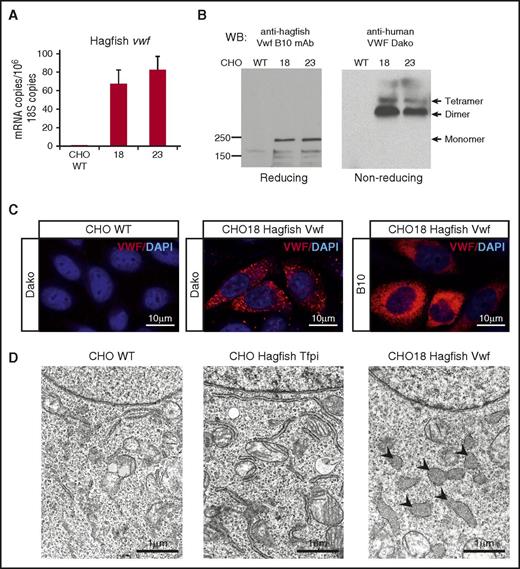

Heterologously expressed hagfish Vwf in CHO cells forms Vwf multimers

To establish whether the cloned gene product undergoes processing and multimerization, we stably transfected CHO cells with full-length hagfish vwf. Although CHO cells lack a pathway for regulated secretion, they have previously been shown to cleave pro-vWF and generate high-molecular-weight multimers.46-48 Clones were selected in puromycin-containing culture medium, and hagfish Vwf expression was verified by qPCR (Figure 6A). Cell lysates were subjected to reducing or nonreducing SDS-PAGE followed by western blot analysis using monoclonal anti-hagfish antibody (Figure 6B). Under reducing conditions, 2 major bands were detected that correlated with unprocessed hagfish Vwf (pro-Vwf) at ∼240 kDa and processed mature Vwf at ∼165 kDa. Western blots of nonreducing gels demonstrated the presence of bands consistent with Vwf dimer and tetramer (Figure 6B). Immunofluorescence of the stably transfected clones with either anti-human or anti-hagfish antibodies revealed cytoplasmic staining (Figure 6C) in a pattern similar to that previously described for heterologously expressed human VWF in CHO cells.48,49 In electron microscopic studies, large membrane-bound organelles containing flocculent, electron-dense material were observed in CHO cells expressing hagfish Vwf (Figure 6D). These structures, which resemble dilated endoplasmic reticulum, were not present in untransfected cells or in control cells expressing hagfish tissue factor pathway inhibitor. In summary, cloned hagfish Vwf expressed in CHO cells undergoes cleavage of the pro-Vwf to generate the mature subunit and undergoes partial multimerization.

Hagfish VWF forms multimers in mammalian cell culture. (A) qPCR analysis of hagfish vwf in untransfected CHO cells (CHO WT) and CHO cells stably transfected with hagfish vwf (clones 18 and 23). mRNA expression is represented as copy number per 106 18S copies. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 fish). (B) Heterologous expression of hagfish Vwf in CHO cell culture visualized by western blotting of whole-cell lysates on reducing or nonreducing SDS-PAGE with B10 anti-hagfish mAb or Dako anti-human pAb, as indicated. (C) Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of control CHO cells (CHO WT) or CHO cells stably transfected with hagfish Vwf (CHO18 Hagfish Vwf) processed for staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) or monoclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody (B10). All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. (D) Electron micrographs of control CHO cells (CHO WT) and CHO cells expressing hagfish tissue factor pathway inhibitor (CHO Hagfish Tfpi) or hagfish Vwf (CHO18 Hagfish Vwf). Nucleus appears at the top of each cell. Note the large irregularly shaped organelles (arrowheads) in the Vwf-expressing cells which contain electron dense material.

Hagfish VWF forms multimers in mammalian cell culture. (A) qPCR analysis of hagfish vwf in untransfected CHO cells (CHO WT) and CHO cells stably transfected with hagfish vwf (clones 18 and 23). mRNA expression is represented as copy number per 106 18S copies. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 fish). (B) Heterologous expression of hagfish Vwf in CHO cell culture visualized by western blotting of whole-cell lysates on reducing or nonreducing SDS-PAGE with B10 anti-hagfish mAb or Dako anti-human pAb, as indicated. (C) Representative confocal laser scanning microscopy images of control CHO cells (CHO WT) or CHO cells stably transfected with hagfish Vwf (CHO18 Hagfish Vwf) processed for staining of Vwf using polyclonal anti-human VWF antibody (Dako) or monoclonal anti-hagfish Vwf antibody (B10). All stain and magnification information for photomicrographs is provided in the supplemental Material. (D) Electron micrographs of control CHO cells (CHO WT) and CHO cells expressing hagfish tissue factor pathway inhibitor (CHO Hagfish Tfpi) or hagfish Vwf (CHO18 Hagfish Vwf). Nucleus appears at the top of each cell. Note the large irregularly shaped organelles (arrowheads) in the Vwf-expressing cells which contain electron dense material.

Structures of the A domains of hagfish VWF by homology modeling

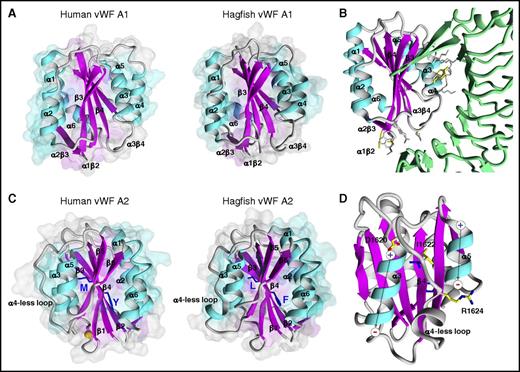

Structural models of VWF A domains are important tools for investigations into sequence and structure relationships, including potential ligand binding and ADAMTS13 cleavage. With that in mind, we carried out homology modeling of hagfish Vwf A1 and A2 domains. Similar to previously determined human or murine VWF A domain structures,50-53 hagfish Vwf A1 and A2 each demonstrated VWA α/β folds, with a β-sheet core composed of 6 β-strands encircled by a series of α-helices (Figure 7). The A1 homology structure showed a main chain root mean squared deviation of 0.875 Å over 191 aligned residues with 27% sequence identity (supplemental Table 2) to experimentally determined human A1 (PDB ID 1AUQ). The A2 homology structure showed a main chain root mean squared deviation of 0.477 Å over 164 aligned residues with 30% sequence identity (supplemental Table 2) to experimentally determined human VWF A2 (PDB ID 3ZQK) (Figure 7). The ADAMTS13 cleavage site from hagfish Vwf (F1611 and L1612) superimposes on its human counterpart (Y1605 and M1606) in the β4-strand.

Hagfish VWF A1 and A2 domain structures. (A) Comparative model of hagfish A1 (backbone ribbon representation on surface volume renderings) in comparison with the experimentally determined human A1 structure (PDB ID 1AUQ). The structures are highly superimposable with the exception of α4, where hagfish is truncated by 4 residues, similar to known bird, amphibian, and fish sequences, impacting the length of the helix and β4α4 loop conformation. (B) Superimposition of the hagfish A1 onto experimentally determined human A1 bound to GPIbα (green ribbon) (PDB ID 3SQ0). The many amino acids shown to contribute to the GPIbα binding interface that are conserved in hagfish A1 are highlighted (gray sticks) along with those few not conserved in hagfish A1 (yellow sticks). In addition, charge is conserved between hagfish and human among 5 of the 7 electrostatically charged residues, as is the hydrophobic character of 3 of 4 residues. (C) Comparative model structure of hagfish A2 in comparison with the experimentally determined human A2 structure (PDB ID 3ZQK). Like human, hagfish A2 is distinguished from other VWA domains by a relatively long unstructured loop at helix 4 (α4). (D) Modeling of the α4-less loop environment in hagfish A2. The α3- and α5-helix dipole moments are symbolized. The strictly conserved buried hydrophobic I1622 side chain atoms, and D1620 N-cap and R1624 C-cap side chain atoms are shown (yellow sticks). Although the hagfish α4-less region contains 5 additional residues compared with human, the α4-less loop environment is well conserved.

Hagfish VWF A1 and A2 domain structures. (A) Comparative model of hagfish A1 (backbone ribbon representation on surface volume renderings) in comparison with the experimentally determined human A1 structure (PDB ID 1AUQ). The structures are highly superimposable with the exception of α4, where hagfish is truncated by 4 residues, similar to known bird, amphibian, and fish sequences, impacting the length of the helix and β4α4 loop conformation. (B) Superimposition of the hagfish A1 onto experimentally determined human A1 bound to GPIbα (green ribbon) (PDB ID 3SQ0). The many amino acids shown to contribute to the GPIbα binding interface that are conserved in hagfish A1 are highlighted (gray sticks) along with those few not conserved in hagfish A1 (yellow sticks). In addition, charge is conserved between hagfish and human among 5 of the 7 electrostatically charged residues, as is the hydrophobic character of 3 of 4 residues. (C) Comparative model structure of hagfish A2 in comparison with the experimentally determined human A2 structure (PDB ID 3ZQK). Like human, hagfish A2 is distinguished from other VWA domains by a relatively long unstructured loop at helix 4 (α4). (D) Modeling of the α4-less loop environment in hagfish A2. The α3- and α5-helix dipole moments are symbolized. The strictly conserved buried hydrophobic I1622 side chain atoms, and D1620 N-cap and R1624 C-cap side chain atoms are shown (yellow sticks). Although the hagfish α4-less region contains 5 additional residues compared with human, the α4-less loop environment is well conserved.

Reduced tensile force requirement for hagfish A2 domain unfolding

The application of tensile force leads to unfolding of the A2 domain and exposure of the ADAMTS13 cleavage site. Previous molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with human A2 demonstrated that force-induced unfolding begins at the C-terminus and proceeds with secondary structure elements sequentially unfolding.54,55 Separation of the C-terminal helix α6 from the rest of A2 and exposure of a “C-terminal hydrophobic core” located near A1661 constitutes a major rate-limiting step. Because hagfish have extremely low blood pressures, we hypothesized that hagfish A2 would demonstrate less stability and enhanced susceptibility to ADAMTS13 than human A2. Indeed, similar MD simulations carried out with modeled hagfish A2 suggested that a conserved C-terminal hydrophobic core in hagfish Vwf A2 was partially exposed in the absence of force and required a lower tensile force to expose the C-terminal hydrophobic core and initiate unfolding of A2 compared with its human counterpart (supplemental Figures 7-8).

A search of Ciona genomes does not reveal evidence of a Vwf gene

To determine whether Vwf is expressed in the closest invertebrate relatives of hagfish, we searched available sequences from sea squirt Ciona intestinalis (database version 82.3/assembly GCA_000224145.1) and Ciona savignyi (database version 82.2/draft assembly CSAV2.0) using BLAST tools for protein sequence and domain similarity to hagfish Vwf. Search of C intestinalis yielded 17 hits, the most similar being a “Vwf-like” gene that lacks all A domains, the D4N domain, and C-terminal domains corresponding to C2-C4 (supplemental Figure 9), and furthermore, contains large sequence insertions in multiple regions that have no known similarities. Search of C savignyi revealed 19 hits, with 2 showing similarity to hagfish Vwf (supplemental Figure 9). One sequence (SAV2) aligns only with the N-terminal 3 VWD regions and beyond that shares no sequence or domain structure with vertebrate VWF. The second sequence (SAV1) has the greatest alignment and domain conservation to hagfish Vwf. It contains 3 sequential A domains, 1 D domain (VWD-C8-TIL), and 3 additional incomplete D domains (containing C8-TIL-E, VWD-C8, VWD-C8 modules, respectively). The furin cleavage site is not conserved. The C-terminal domain differs from vertebrate VWF in lacking repeats of cysteine-rich C-domain sequences. Interestingly, cysteine residues that mediate interchain disulfide bond dimerization (Cys1099, Cys1142, Cys2771, and Cys 2773) are conserved between human VWF and SAV1. Together with the absence of a closed circulatory system and thrombocytes in urochordates, these findings argue against the presence of a functional VWF in these organisms.

Discussion

Hagfish and lamprey (cyclostomes), referred to as agnathans or jawless fish, lack a hinged jaw, and their skeleton is not mineralized. They are the sole survivors of the agnathan stage in vertebrate evolution and are the closest extant outgroups to all jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes). Their immediate nonvertebrate relatives are the Urochrodata (tunicates) and Cephalochordata (amphioxus). The last common ancestor of hagfish and jawed vertebrates (cartilaginous fish [chondrichthyes] and the bony fishes [osteichthyes], amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) was also the last common ancestor of all extant vertebrates. Features that are shared between hagfish and gnathostomes can be inferred to have already been present in this ancestral vertebrate. We have shown that hagfish, like jawed vertebrates (gnathostomes), express a functional Vwf. Our search of Ciona databases failed to reveal compelling evidence of Vwf in urochordates. These findings suggest that Vwf evolved following the divergence of urochordates from the vertebrate lineage, >500 million years ago.

Several features of hagfish Vwf are shared with its mammalian counterpart. For example, hagfish Vwf is expressed both in endothelial cells and in a subpopulation of nucleated peripheral blood cells consistent with thrombocytes. In addition, hagfish endothelium possesses WPBs, as evidenced by our electron microscopy studies. The punctate staining of Vwf in hagfish endothelium suggests that the protein is packaged and stored in these organelles. By extension, these data suggest that the release of Vwf from hagfish endothelial cells is regulated, at least in part, by an inducible pathway, as it is in humans and mice.

In mammals, VWF is differentially expressed between and within different vascular beds.37 For example, VWF is undetectable in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells of the mouse and demonstrates patchy expression in capillaries of the heart and in the aorta. In contrast, hagfish Vwf was detected throughout the endothelium of all vascular beds examined, including the aorta. Although definitive proof for ubiquitous expression would require colocalization studies with a pan-endothelial marker (which to our knowledge is not available for hagfish), our findings suggest that vascular bed–specific expression of VWF evolved following the divergence of hagfish. We recently demonstrated that VWF expression in mice is regulated by a bistable switch whose state-switching dynamics vary across the vascular tree.56 The finding that hagfish Vwf is expressed in all endothelial cells suggests that expression is locked into a single ON state and is impervious to the effects of biological noise or organ-specific extracellular cues.

Similar to higher vertebrates, hagfish Vwf circulates in a multimerized form. Interestingly, hagfish plasma demonstrated smaller multimers compared with humans. Previous studies of mammalian VWF have shown that the hemostatic function of VWF, including its binding to collagen and GPIbα, decreases as the multimer size decreases.57 Presumably, the reduced multimer size in hagfish is sufficient to mediate thrombocyte-subendothelial interactions in these animals. We also demonstrated that hagfish Vwf has a partially conserved ADAMTS13 cleavage site and is cleaved by human ADAMTS13. Thus, it likely that hagfish Vwf is not only secreted as a high-molecular-weight multimer, but that its size is regulated by an ADAMTS13-like protease.

Hagfish Vwf contains a highly conserved GPIbα binding site in the A1 domain. Previous studies in mammals have shown that A1 binds GPIbα under conditions of high shear stress at sites of vascular injury.58,59 A recent study employing MD simulations, atomic force microscopy, and microfluidic experiments demonstrated that the human VWF A2 domain normally blocks the GPIbα-binding site in A1.60 This autoinhibition was relieved when VWF was exposed to a stretching force (mimicking shear stress), resulting in A2 domain unfolding prior to ADAMTS13-mediated cleavage. In our simulations, we found that compared with human, the C-terminal helix of hagfish A2 requires a lower force to be undocked. Hagfish have the lowest blood pressures of all vertebrates, with systolic pressures in the dorsal aorta measuring a mere 5.8 to 9.8 mm Hg.61 Thus, it is interesting to speculate that a lower threshold for force-mediated reversal of the A2-A1 interaction is adapted to low-flow conditions. Similarly, our MD simulations suggested that the C-terminal hydrophobic core is partially exposed in hagfish A2, which may explain why the threshold for force-mediated unfolding is lower in hagfish compared with human VWF. This property would not only facilitate thrombocyte binding under low-flow conditions, but would also enhance ADAMTS13 cleavage of Vwf, perhaps contributing to the relatively narrow spectrum of multimers observed in hagfish plasma.

A remarkable finding in the present study is that the hagfish vwf gene lacks certain domains critical for VWF function in higher vertebrates. Most notable is the absence of the A3 domain which suggests that hagfish Vwf does not bind fibrillar collagen (types I and III). In humans, mutations that affect collagen binding in A3 are associated with a bleeding phenotype.62 In contrast, hagfish Vwf A1 domain is conserved and likely mediates binding to collagen types IV and VI. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that VWF A3-collagen interactions occur only under conditions of high shear, whereas type VI collagen demonstrates VWF-dependent platelet binding under conditions of low shear.63 vWF may have evolved in the ancestral vertebrate as a critical mediator of platelet adhesion to the subendothelial matrix under low-flow conditions, with the A3 domain appearing in later vertebrates as an adaptation to higher blood pressures and shear rates. An alternative explanation is that the A3 domain was lost in the hagfish lineage after its split from the other vertebrate lineages. Indeed, it is interesting to speculate that A3 domain loss is a derived feature of VWF in other vertebrates with extremely low blood pressures.

The carboxyl-terminal domains of VWF, D4-CTCK, are cysteine rich. A recent study demonstrated that the cysteine amino acids in the VWD4, C1, C5, C6 domains and N-terminus of the CTCK domain are important for the precise folding of C-terminal domains.64 It was hypothesized that mutations eliminating these cysteine residues might influence dimeric bouquet formation and consequently helical assembly of tubules and storage. It is tempting to speculate that the absence in hagfish Vwf of D4N, VWD4-C8-4-TIL-4 (previously D4) and C1 (previously B1) helps explain the small size of hagfish Vwf multimers compared with mammals.

VWD and VWA domains have each been identified in protists, suggesting that they were early inventions during eukaryotic evolution.65,66 VWD in combination with the C8 domain appears in choanoflagellates, whereas VWD domains containing 3 repeats of VWD-C8-TIL is first observed in ctenophores.66 In vertebrates, the VWD-C8-TIL repeats combine with other domains to form mucins and nonmucin proteins, including VWF. The addition of a PTS domain is characteristic of mucins, whereas the addition of VWA is a hallmark of VWF. Indeed, the combination of VWD and VWA domains has not been previously identified in any other protein in vertebrates or C intestinalis, leading others to conclude that VWF is unique to vertebrates.67 In our own bioinformatics search, we discovered a sequence in the C savignyi database that contains 1 complete and 3 incomplete D domains together with 3 tandem A domains. Because this combination has not been described in any other gene, we suggest that the A-D domain motif is orthologous, and that 1 of the A domains was lost in hagfish (1 event). A less parsimonious interpretation is that the ancestor had 2 A domains (retained in hagfish), and there have been 2 independent gains in C savignyi and gnathostomes (2 events). Alternatively, the ancestral gene had 3 A domains, 1 was lost in the ancestor of hagfish and gnathostomes, and a third A domain was gained in gnathostomes (2 events). In contrast to the striking homology of the A-D domain architecture, the predicted structure of the C savignyi protein lacks many of the key features of VWF, including C-terminal repeats of cysteine-rich C domains and is thus at best considered a partial ortholog of vertebrate VWF.

In summary, our findings suggest that VWF and primary hemostasis arose during a narrow window of time following the divergence of the urochordates from the ancestral vertebrate, and that it was initially adapted to a low-flow, low-pressure cardiovascular system. In future studies, it will be interesting to carry out structure-function relationships of hagfish Vwf and determine whether the gene is involved in processes other than primary hemostasis, including the binding of a factor V/VIII precursor.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lauren Janes, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, for providing technical expertise; and J. Evan Sadler, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, and David A. Haig, the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, for their valuable insights.

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL086766) (M.A.G.), (HL119322) (W.C.A.), (HL117639-01 and HL112633) (J.A.L.), and career development award (K25HL118137) (G.I.). Simulations were performed on the Comet supercomputer at the San Diego Supercomputing Center thanks to an XSEDE allocation (TG-MCB060069N) (G.I.), which is made available in part through National Science Foundation support.

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.G. and W.C.A. conceived the study; M.A.G., D.L.B., K.C.S., J.C., H.D., T.E.S., and G.I. performed the experiments; M.A.G., W.C.A., A.M.D., and J.A.L. advised on experimental design and data analysis; M.A.G., W.C.A., and G.I. wrote the manuscript; and all authors contributed to the discussion of the data and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marianne A. Grant, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Center for Vascular Biology Research, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: mgrant@bidmc.harvard.edu.