Abstract

The standard treatment of relapsed multiple myeloma has been either lenalidomide-dexamethasone (RD) or bortezomib-dexamethasone (VD) but it is changing rapidly for 2 reasons. First, lenalidomide and bortezomib are currently used in frontline treatment and many patients become resistant to these agents early in the course of their disease. Second, 6 second-line new agents have been recently developed and offer new possibilities (pomalidomide, carfilzomib and ixazomib, panobinostat, elotuzumab, and daratumumab). Recent randomized studies have shown that triple combinations adding 1 of these new agents (except pomalidomide) to the RD or VD regimens were superior to the double combinations in terms of response rate and progression-free survival (PFS). Their place in the treatment of first relapse is discussed here. Among these agents, daratumumab is clearly a breakthrough and daratumumab-based combinations might become the preferred option in the near future. However, all of these drugs are expensive and are not available or affordable in all countries. We propose a decision algorithm for first relapse in fit patients with the objective of achieving the best PFS. The choice of salvage regimen is based on lenalidomide/bortezomib resistance, daratumumab availability, and cost. Autologous transplantation should be considered in younger patients if not used upfront.

Introduction

Prognosis of multiple myeloma (MM) has considerably improved in the past few years, mostly due to the introduction of immunomodulatory drugs (IMIDs) and proteasome inhibitors (PIs), initially in relapsed disease and very rapidly in frontline treatment. For newly diagnosed patients, 2 new concepts have been evaluated recently:

Triple combinations including 1 IMID and 1 PI (usually lenalidomide and bortezomib) for induction treatment1-5 ; and

Prolonged treatment with lenalidomide or bortezomib6 : either maintenance treatment after high-dose therapy plus autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT/ASCT) in younger patients7,8 or continuous therapy in elderly patients.9,10

These new strategies have dramatically increased the depth of response, with a higher complete remission (CR) rate, and progression-free survival (PFS). Moreover, it is now possible to achieve a high level of tumor burden reduction leading to negative minimal residual disease (MRD) as assessed by sensitive methods such as next-generation flow cytometry and next-generation sequencing.11 MRD negativity is associated with prolonged PFS and possibly long overall survival (OS).12,13 In younger patients treated with IMIDs plus PI before and after HDT/ASCT, median PFS may be over 5 years and median OS may exceed 10 years.14-16 And the hope of cure for some patients becomes reality.17

However, the great majority of patients ultimately relapse and treatment of relapse remains a major challenge. Because MM has become a chronic disease with a longer succession of remissions and relapses, finding an effective treatment at each consecutive relapse is critical for prolonging OS. This is increasingly difficult along the course of the disease because increasing drug resistance reduces therapeutic possibilities and remission duration with each successive regimen.18

In the past, treatment for relapsed MM was thalidomide-dexamethasone (TD). Due to its frequent toxicity, thalidomide has been replaced in most high-income countries by lenalidomide. Lenalidomide-dexamethasone (RD) and bortezomib-dexamethasone (VD) combinations have become standard of care, after publication of large randomized studies vs dexamethasone alone.19-21 But the landscape of relapsed MM treatment is constantly evolving. Large use of lenalidomide and bortezomib for both newly diagnosed and relapsed patients has increased the proportion of patients with MM refractory to 1 agent or both. Prognosis of patients who are resistant to both bortezomib and lenalidomide is poor.22 But in the same time, new possibilities have emerged with approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) of no less than 6 new agents since 2012: a new IMID (pomalidomide23-27 ), new PIs (carfilzomib28,29 and ixazomib30 ), and drugs with different modes of action like histone-deacetylase inhibitors (panobinostat31 ) and antibodies (elotuzumab32 and daratumumab33-35 ). Reviews on the treatment of relapsed MM have been recently published36-39 but they do not include the most recent results, especially those with daratumumab.

General considerations

Available therapies

Clinical efficacy of second-line new agents given alone or with dexamethasone in phase 2 trials23-35 is summarized in Table 1. Rate and duration of response, and PFS, depend on the inclusion criteria (number of prior lines of treatment, resistance to lenalidomide/bortezomib). However, these trials have shown the efficacy of pomalidomide, carfilzomib, ixazomib, and daratumumab in heavily pretreated patients, including patients refractory to bortezomib, lenalidomide, or both. Efficacy of panobinostat and elotuzumab has been evaluated directly in combination after phase 1 trials.31,32 Safety data33-35,40-47 are shown in Table 2.

These new agents have also been tested in combination with older ones in phase 2 trials (Table 3).48-54 We now have several therapeutic classes, which can be combined in multiple ways, leading to a large variety of possibilities at each stage of the disease. Moreover, HDT/ASCT and allogeneic stem cell transplantation can still be proposed for relapsed MM therapy. Their indications have been recently reviewed.37,55

Randomized trials in relapsed MM have shown the superiority of triple combinations (triplets) containing 2 new agents compared with double combinations (doublets) with only 1 new agent. The first of these trials showed that, in first relapse after HDT/ASCT, bortezomib-thalidomide-dexamethasone (VTD) was superior to TD in terms of response rate, PFS, and OS.56

More recently, 7 large randomized trials compared triplets with the addition of 1 new agent to 1 of the backbone combinations, either RD57-60 or VD61-64 ; these trials are summarized in Table 4.

The triplet was always superior to the standard doublet in terms of response rate and PFS. However, the follow-up of these studies was generally short and, at time of publication, the benefit in terms of OS was not always significant. This may be partly due to the multiple possibilities of salvage treatment at the time of subsequent relapses.

Parameters to consider at relapse

Relapse MM is a heterogeneous situation and there are multiple parameters that can impact the result of relapsed MM treatment. They have been listed in recent reviews36,37 and are summarized in Table 5.

Disease-associated parameters are mostly prognostic factors and have currently little impact on the choice of treatment. Compared with RD or VD, triplets improve PFS both in standard-risk and in high-risk patients as defined by β2-microglobulin57-60 or International Staging System (ISS),57,59,64 and by cytogenetics,57-59 although they do not abrogate the poor prognosis associated with high-risk cytogenetics.65 Moreover, there is currently no targeted therapy that might be more active in specific prognostic subgroups. Therefore, triplets should be preferred whatever the prognostic factors, including cytogenetics. Some patients have very aggressive relapse with rapid onset and, for instance, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, or extramedullary disease. These patients require immediate treatment, usually with a triplet including 1 IMID and 1 PI.37,39

Patients’ characteristics are important for determining the benefit-to-risk ratio of a given treatment. Age and comorbidities are major factors to consider at the time of choosing relapse treatment. Again, triplets were superior to standard doublets even in older patients and in patients with renal dysfunction.57-60,64,66 However, clinical trials do not reflect real life because frail patients and patients with end-stage renal failure are usually excluded. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status or frailty index67 should be considered in elderly patients. Comorbidities and adverse events of previous treatments can serve to exclude 1 of these agents because of its specific toxicity. All-oral combinations may be preferred by some patients, particularly those living far from the hospital.

Previous treatment parameters were:

A previous ASCT and the interval between ASCT and relapse define the indication of ASCT at relapse.37,55

The number of prior lines of treatment is an important prognostic factor and an inclusion factor in clinical trials. Pomalidomide has been developed mostly in heavily pretreated patients40 and panobinostat is more active in patients with 2 prior lines or more.62 Carfilzomib, ixazomib, and daratumumab combinations are superior whatever the number of lines (1-3).59,68,69

The prior use and results of IMIDs and PIs are becoming important issues. Patients with prior treatment are bortezomib- or lenalidomide-exposed; others are bortezomib- or lenalidomide-naive. A patient who previously responded to a given agent without major toxicity can be re-treated at relapse with the same agent or with an agent of the same class.37 More difficult is the treatment of refractory patients. According to International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria, refractoriness is defined by progression occurring on therapy or <60 days after the end of therapy, or by intolerance leading to treatment interruption.70

Currently, most frontline-therapy protocols use bortezomib and/or lenalidomide and continuous therapy, which explains why at the time of relapse many patients may be resistant to these agents.

Goal of treatment

In end-stage disease and in frail patients, quality of life may be a realistic objective and primarily nontoxic treatments may be preferred even if they are less active. But for the majority of patients, the main objective of relapse treatment is OS. Each relapse treatment is obviously important for OS prolongation but the choice at first relapse is critical because subsequent relapses are usually shorter.18 How should this decision be approached? Comparison of results achieved in phase 2 studies is unwise because inclusion and exclusion criteria vary across studies. Therefore, the best way is to use randomized phase 3 trials. Some years ago, in the chemotherapy era, there was no standard of care for relapsed myeloma and first-line new agents were randomly compared with high-dose dexamethasone. A significant OS benefit was thus demonstrated for bortezomib,19 lenalidomide,20,21 and pomalidomide.71 Second-line new agents are now compared with more active standards (either RD or VD). But due to improvement in relapse treatments, differences in OS curves may appear late. The response rate, and mostly the CR rate, is a good indicator of treatment efficacy, and some data suggest a relationship between the depth of response and the final outcome even in the relapse setting.72-74 But the primary objective of recent randomized studies in relapsed MM has been PFS, mostly to satisfy registration requirements and to facilitate early market access. A PFS benefit is now the argument of choice particularly at first relapse, with the hope that a significantly longer PFS will translate into an improved OS. Results of the randomized Castor et al64 and Pollux et al60 studies, which compared triplets including daratumumab to the standard VD and Rd, have generated great enthusiasm with dramatic superiority of the daratumumab-containing combinations. Unprecedented hazard ratios (HRs) for PFS of 0.39 in the daratumumab-VD trial and of 0.37 in the daratumumab-Rd trial have been achieved. Moreover, in these trials, negative MRD could be achieved and was 3.5 to 5 times higher with the triplet than with the doublet.75 Daratumumab allowed some patients with high-risk cytogenetics to achieve negative MRD. Therefore, daratumumab represents a landmark advance in the treatment of MM,76 and daratumumab-based combinations will certainly be the first choice in relapsed MM in the near future.

Case studies

The following case studies selected from the Intergroupe Francophone Du Myelome (IFM) protocols will illustrate different situations that currently occur with the recently used strategies for frontline therapy.

A transplant-eligible patient relapsing after velcade revlimid dexamethasone (VRD) induction, HDT/ASCT, and 1 year of maintenance with lenalidomide

In June 2011, a 53-year-old man without comorbidities was diagnosed with an ISS1 IGgkappa MM. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a single vertebral collapse. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis revealed no t(4;14) and no del(17p).

He was included in the IFM 2009 trial that compared novel agents plus upfront HDT/ASCT and novel agents alone with HD/ASCT at relapse. He was randomized in the upfront transplant arm and received the whole treatment (3 induction courses with revlimid velcade dexamethasone [RVD], HDT/ASCT, 2 courses of RVD consolidation, and 1 year of lenalidomide maintenance). The treatment was stopped in January 2013.

He was in very-good-partial response (VGPR) after induction treatment, in CR after HDT/ASCT, and still in CR at the end of maintenance treatment. In March 2016, a small peak (2.4 g/L) was present at serum electrophoresis. Because he was asymptomatic and very active, no treatment was decided. Control electrophoresis every 2 months showed a gradual increase in the M-component level which reached 12.5 g/L in September 2016. The patient was still asymptomatic but was concerned by this increase and treatment with carfilzomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone was started.

The first question is the date of treatment initiation. When the relapse is symptomatic, treatment should be rapid to relieve symptoms and to avoid end-organ damage.37,39 In this case, the patient had a biochemical relapse without symptoms and usually these patients with a slow rise in the paraprotein level are managed with a stringent watch-and-wait approach. The question is then when to start, if possible, before the occurrence of symptoms. A doubling time of the monoclonal component of 3 months or less would suggest starting treatment.37

The second question is the choice of therapeutic regimen. In the past, this patient would have received a standard RD regimen because he is lenalidomide-exposed but lenalidomide-sensitive. This would be preferred to the other standard VD: although no randomized study directly compared RD and VD in relapse, the recent randomized trials comparing triplet and doublet RD or VD show that longer PFS is achieved with RD partly because the treatment can be administered longer.57-64

Four of these randomized studies were lenalidomide-based and included comparable populations of patients.57-60 Among the evaluated triplets, the daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone combination clearly yielded the best results with impressive CR rate and PFS.60 The HR for PFS was much higher than for the other combinations57-59 (0.37 vs 0.69 to 0.74). The combination daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone will become the treatment of choice.

However, daratumumab is not yet available in many countries and this expensive combination has just been approved by the FDA and EMA.

Other alternatives can thus be proposed. Because the patient remains bortezomib-sensitive, an IMID (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) plus PI combination is logical. As VRD is superior to RD in the frontline setting,5 one can speculate that it is also superior to RD in the relapse setting. Should the new regimens with carfilzomib (karfizomib revlimid low dose-dexamethasone [KRd]) or ixazomib (ixazomib revlimid low-dose dexamethasone [IRd]) be preferred to VRd? No randomized study has compared VRd and either KRd or IRd. However, carfilzomib may be effective in bortezomib-refractory patients.28 One head-to-head comparison of carfilzomib and bortezomib in the relapse setting (the Endeavor study) is clearly in favor of carfilzomib but the dose of carfilzomib used in this study is higher than the first approved one (57 mg/m2 vs 27 mg/m2)77 . In another head-to-head comparison in the frontline setting using the dose of 36 mg/m2, there was no difference between carfilzomib and bortezomib combined with melphalan-prednisone.78 The choice of PI should be more based on safety issues and patient’s comorbidities than on efficacy differences. With carfilzomib, the incidence of peripheral neuropathy is much lower than with bortezomib and severe neuropathy is rare.42,57,77 However, this drug may cause more cardiac complications (hypertension, cardiac failure, or ischemic heart disease)42,77,79 and should be used cautiously in patients with cardiac problems. Ixazomib is well tolerated and an all-oral combination such as IRd may be useful in older patients or in patients living far from the hospital. In countries where elotuzumab is available, the elotuzumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone combination is an alternative option in particular in elderly patients because it is well tolerated and largely superior to Rd in this subgroup of patients.58

And in countries with lower income or when coverage is not optimal, generic bortezomib is preferred and cheaper combinations like VTD or velcade cyclophosphamide dexamethasone (VCD) may be alternative options.

The third question is the indication of HDT/ASCT. According to the recently published guidelines, a second HDT/ASCT may be considered because relapse occurs >2 years after the first.37,55 However, this statement is based on studies that were mostly performed before the wide use of new agents. Only 1 randomized study compared a second HDT/ASCT and nonintensive treatment of post-HDT/ASCT relapse.80 It was in favor of the HDT/ASCT but the control arm was conventional-dose chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, which is no longer considered a standard relapse treatment in the era of novel agents. Further studies are needed to determine the benefit of a second HDT/ASCT compared with nonintensive treatments. In the United States, many transplant-eligible patients do not undergo HDT/ASCT upfront but are initially treated with RVD and transplanted at relapse. The IFM 2009 trial compared RVD with HDT/ASCT at relapse and RVD induction and consolidation plus HDT/ASCT.16 The current results with 43 months median follow-up show a significantly longer PFS with upfront HDT/ASCT but no difference in OS between the 2 arms, meaning that delayed HDT/ASCT is a valuable option.

A transplant-eligible patient with ISS3 and high-risk cytogenetics relapsing while receiving lenalidomide maintenance

A 54-year-old man without significant medical history was diagnosed with κ light-chain MM in January 2011. The initial workup showed ISS3, bone lesions, and presence of adverse cytogenetics, t(4;14) and del(17p). He was included in the upfront ASCT arm of the IFM 2009 trial. After the RVD induction treatment, he was in CR and remained in CR after HDT/ASCT and 2 courses of RVD consolidation. He relapsed after 6 months of lenalidomide maintenance and was then treated with VCD. HDT/ASCT was not proposed.

Some investigators consider that when relapse occurs during low-dose lenalidomide maintenance, increasing the dose of lenalidomide or adding a new agent may be effective, at least in standard-risk patients. In our experience, salvage treatment with lenalidomide yields poor results8 in this setting and this patient was considered lenalidomide-refractory. But because he responded to the VRD induction therapy and relapsed >6 months after VRD consolidation, PI might be used. Bortezomib partly overcomes the poor prognosis associated with t(4;14).81,82 Data regarding its efficacy in del(17p) is more debated.81-83 A combination of bortezomib plus cyclophosphamide (VCD or cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [CyBorD]) is a reasonable choice.

Regarding the combinations of bortezomib with newer agents, again, the magnitude of benefit achieved with daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone64 is largely superior to other combinations with bortezomib (HR for PFS 0.39 vs 0.63 and 0.72).61,63 When reimbursed, this combination will be the first choice in lenalidomide-refractory patients. Other new combinations with bortezomib (elotuzumab or panobinostat plus bortezomib/dexamethasone) appear less attractive, at least in first relapse.

Pomalidomide has shown efficacy in patients with high-risk features including adverse cytogenetics.84 Therefore, another alternative would be a combination of pomalidomide with VD which yields promising results50 and is currently being evaluated in a phase 3 trial, or a cheaper one with cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone.49 Even lenalidomide in combination with low-dose cyclophosphamide and prednisone (REP) offers a therapeutic perspective in lenalidomide-refractory patients.85

Some patients may be resistant to both lenalidomide and bortezomib at first relapse. This situation occurs more frequently with larger use of these 2 agents upfront. Second-generation PI may be tested specially in case of bortezomib intolerance. Again, pomalidomide, which has activity in double-refractory patients24-26 may be used in combination with dexamethasone plus cyclophosphamide.49 Daratumumab in monotherapy was tested in heavily pretreated patients35 including double refractory patients and responses were observed in 29% of cases and median PFS was 4 months. Combinations of daratumumab plus lenalidomide or bortezomib plus dexamethasone have shown activity in patients previously exposed to lenalidomide/bortezomib but double-refractory patients have not been included in these trials. This situation remains actually as an unmet medical need and, if possible, these patients should be included in clinical trials evaluating new drugs.

Because relapse occurred shortly after HDT/ASCT (<2 years), there is no indication for salvage ASCT. However HDT/ASCT could be proposed as a bridge to reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation (tandem auto-allo transplantation).55,86,87 When a suitable donor is available, allogeneic stem cell transplantation remains a difficult choice. Treatment-related toxicity has been decreased by reduced-intensity conditioning regimens but graft-versus-host disease morbidity and mortality is still too high in standard-risk patients, and, in high-risk patients, relapses are frequent.86,87 Therefore, allogeneic transplantation should not be performed routinely out of a clinical trial in selected patients with high-risk disease.37,55

An elderly patient relapsing after MPT in the First trial

In March 2012, a 73-year-old patient with weight excess, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes was diagnosed with a Revised International Staging System (RISS) 188 MM. He was randomized in the mephalan prednisone thalidomide (MPT) arm of the First trial, which compared 18 cycles of MPT, 18 cycles of Rd, and Rd until progression.10 He received the whole treatment and suffered only a mild peripheral neuropathy.

The best response was VGPR. In August 2014, he had a symptomatic relapse with new bone pains. He was then treated with Rd and again achieved a VGPR during 12 months. In September 2015, he had a second relapse that was treated with subcutaneous bortezomib.

At first relapse, this patient was lenalidomide and bortezomib naive and could be treated by both agents. Because of his age and comorbidities the question was whether to use an IMID and a PI simultaneously or sequentially. In elderly fit patients, a triple combination is tolerable and might be preferred. In the SWOG trial for frontline treatment, patients were included whatever the age.5 In the trials comparing RD to either carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (Aspire) or ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone (Tourmaline), elderly patients were also included.57-59

But in frail elderly patients, the benefit of triplets is less evident because they may be more toxic, particularly with regard to hematologic toxicity.89-91 Therapeutic strategies should be defined after careful assessment of the frailty profile. Doses and mode of administration should be adapted. In this case, the decision was made to reduce the risk of toxicity by starting with a RD doublet and to use bortezomib for the second relapse. Subcutaneous bortezomib was preferred to reduce the risk of neurotoxicity.92

Conclusions and questions to be addressed

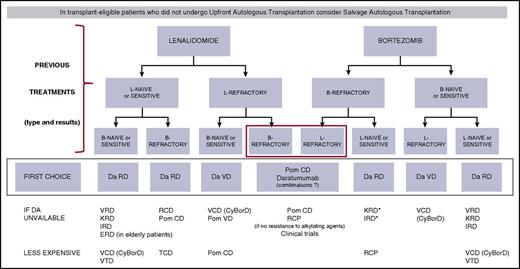

There are many different situations and many possible combinations. Because MM is a chronic disease with successive remissions and relapses, it is important to consider all of the new agents for the treatment of each relapse. It is currently impossible to define the optimal sequence, which has to be adapted on an individual basis. For first relapse treatment in fit patients, a tentative algorithm is shown in Figure 1. The choice is first based on the lenalidomide and bortezomib-sensitive/refractory status. A similar strategy can be used for subsequent relapses. Decisions should obviously be adapted to the patient’s characteristics including age, general condition, renal function, and comorbidities.

Treatment algorithm for first relapse of MM in fit patients. *Mostly if intolerant to bortezomib. B or Bort or V, bortezomib; C or Cy, cyclophosphamide; D, dexamethasone; Da, daratumumab; E, elotuzumab; I, ixazomib; K, carfilzomib; L or R, lenalidomide; P, prednisone; Pom, pomalidomide; T, thalidomide.

Treatment algorithm for first relapse of MM in fit patients. *Mostly if intolerant to bortezomib. B or Bort or V, bortezomib; C or Cy, cyclophosphamide; D, dexamethasone; Da, daratumumab; E, elotuzumab; I, ixazomib; K, carfilzomib; L or R, lenalidomide; P, prednisone; Pom, pomalidomide; T, thalidomide.

One important question regarding all of these new agents is their price, which makes them currently unaffordable in many countries. Triplets with 2 new agents that are very expensive are superior to doublets in terms of response and PFS, but not always or not yet in terms of OS: is this high cost justified only by a PFS benefit? Clinical added value should be carefully analyzed.

Cost-to-effectiveness ratio assessment should be developed93 although current results are variable due to a high level of uncertainty.94,95 In nonaggressive relapses or in patients without high-risk characteristics, clinical trials could be designed to compare simultaneous use of novel agents in triplets vs sequential use (either at subsequent relapse or in case of insufficient results). We also have to address the question of treatment duration, in particular in first relapse where long second remissions will be observed. Finally, we need to update the randomized studies to confirm that, with longer follow-up, the PFS prolongation does translate into an OS benefit. If not, the use of cheaper combinations early in the disease course would be more cost-effective because the duration of therapy decreases with each relapse.93

Daratumumab is certainly a breakthrough for the treatment of MM. Isatuximab, another anti-CD38 antibody, is coming and appears to be very active as well in combinations.96 Like rituximab in B-cell malignancies, it will probably be incorporated not only in relapsed MM but also very rapidly in newly diagnosed patients. As daratumumab is prescribed for long durations, the risk of daratumumab refractoriness might compound the current challenges with double-refractory patients. This underlines the need for a continuous research effort. In addition to newer PI and IMIDs currently under development, there are already encouraging results with novel agents with innovative modes of action. For instance, venetoclax is a potent BCL2 inhibitor developed in B-cell malignancies which has an acceptable safety profile and clear myeloma activity in relapsed and refractory MM with t(11;14) and a high BCL-2 expression level.97,98 Selinexor is a first-in-class selective inhibitor of nuclear export that inactivates exportin 1, which shows activity in heavily pretreated MM and is already tested in combination with other agents.99,100 The HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir may sensitize MM to PI and overcome PI resistance. Interesting results were shown at the last American Society of Hematology meeting with this agent combined with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with bortezomib-refractory MM.101

Finally, in the field of immunotherapy, recent advances that have been developed in other malignancies are currently being tested in MM, such as T cells expressing an anti-BCMA chimeric antigen receptor or anti-PD1 antibodies.102,103

In conclusion, when the first-generation new agents were introduced, OS was dramatically improved, mostly because new solutions were offered at time of relapse.104 We can hope that with the additional possibilities offered by second-generation new agents, OS after relapse will continue to improve.

Authorship

Contribution: J.L.H. and M.A. analyzed the literature and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.L.H. participated in a scientific advisory board on drug pricing sponsored by Janssen. M.A. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jean Luc Harousseau, Groupe Confluent, 4 rue Eric Tabarly, Nantes, 44277 France; e-mail: jean-luc.harousseau@groupeconfluent.fr.