Abstract

Background:

Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) is associated with major morbidity and mortality in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients. Due to the suboptimal response to conventional therapies, extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) has been explored as a possible therapeutic option. However, to date, only a few case series, without control groups, examining the effectiveness of ECP for BOS after HCT ( Del Fante et al, 2016; Lucid et al, 2011 ), have been published. We carried out this first matched case-control study to assess the impact of ECP therapy for BOS after HCT.

Methods:

After IRB approval, our institutional database of 304 consecutive AML patients that underwent allogeneic HCT between 2005 and 2015 was reviewed. A retrospective diagnosis of BOS was made in patients who developed a new obstructive pulmonary function test (PFT) with progressive FEV1 decline of ≥ 10% over 3 months without complete resolution on subsequent testing. Patients with BOS diagnosis were classified into case or control groups according to treatment with or without ECP, respectively. ECP was started on a weekly basis with two apheresis sessions a week followed by gradual taper at the discretion of treating physicians. Methoxsalen was administered at a dose of 0.35 mcg per ml of pheresed buffy coat. Propensity score analysis was performed to match cases with controls on a 1:1 ratio. The rate of change in FEV1 (% change from baseline per month) was calculated using linear regression models. Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare paired data at different time intervals.

Results:

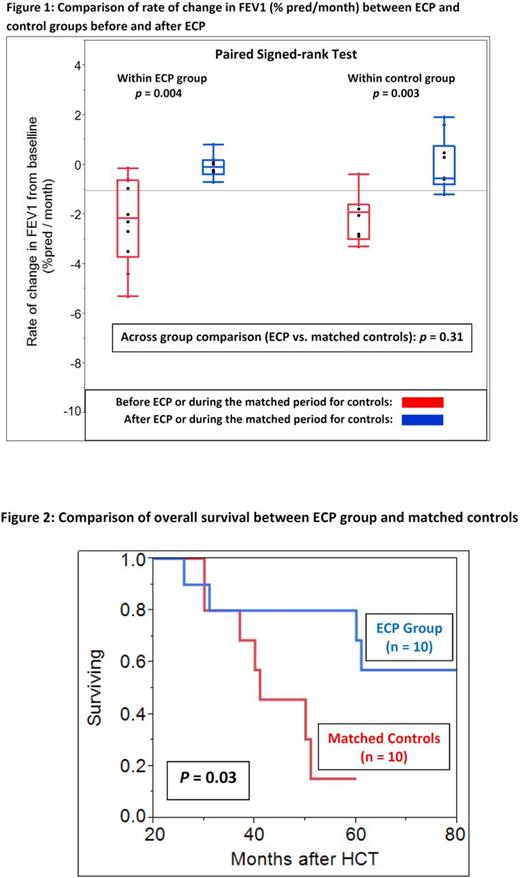

ECP-treated cases consisted of 10 patients (median age 52 years, male 50%), who developed BOS a median of 9 (3-44) months after HCT. ECP was started a median of 9 (range 1-15) months after BOS diagnosis and continued for a median of 50 (range 26-80) sessions. Controls consisted of 24 patients (median age 51 years, male 50%), who developed BOS a median of 10 (range 3-25) months after HCT. There was no significant difference in baseline transplant characteristics between the two groups. Pre-HCT FEV1 was similar between cases and controls (median 92% vs. 99% predicated, p = 0.21). ECP-treated cases, however, had a significantly lower FEV1 at the time of BOS diagnosis (median 48% vs. 68% predicted, p = 0.006) and at six months after non-ECP therapy (median 48% vs. 72% predicted, p = 0.008), consisting of fluticasone/azithromycin/ montelukast (FAM) and/or increased immunosuppression. Propensity score-matched analysis was performed using the covariates of FEV1 nadir and time to FEV1 nadir before ECP initiation or during a matched period for the cases and controls, respectively. Matched controls (n = 10) had similar FEV1 nadir (median 45% vs. 48% predicted, p = 0.76) and time to FEV1 nadir (median 7.5 vs. 9 months, p = 0.81). Within the ECP group, the rate of FEV1 change was significantly more negative before ECP than after ECP (-2.1% / month vs. -0.1% /months; p = 0.004) (Figure 1). Similarly, within the matched control group, the rate of change in FEV1 significantly decreased when periods matched with pre- and post-ECP intervals were compared (median -1.9% / month vs. -0.5% / month; p = 0.03). Across group comparison between ECP and matched controls did not reveal a significant difference in the rate of FEV1 change ( p = 0.31). In spite of comparable rates of FEV1 changes between the two groups, and a higher prevalence of non-pulmonary GVHD observed at the time of BOS diagnosis in the ECP group (90% vs. 40%, p = 0.05), patients treated with ECP had a better overall survival in comparison to matched non-ECP controls (estimated median: NR vs. 41 months, p = 0.03) (Figure 2). Two (50%) of 4 deaths in the ECP group and 4 (57%) of 7 deaths in the non-ECP group were attributed to respiratory failure ± superimposed infection.

Conclusion:

In our retrospective, propensity score-matched analysis, we find that while ECP therapy for HCT patients with BOS did not significantly change FEV1 values in comparison to non-ECP therapies, there was a survival benefit accorded to those treated with ECP. It is plausible that ECP may confer additional benefits that are not reflected in PFTs. This would be best assessed by prospective randomized studies.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.