In this issue of Blood, Ghez et al report on 33 patients who developed invasive fungal infections during ibrutinib treatment, the majority of which were invasive aspergillosis, which supports the observation that fungal infections are a potential risk with ibrutinib.1

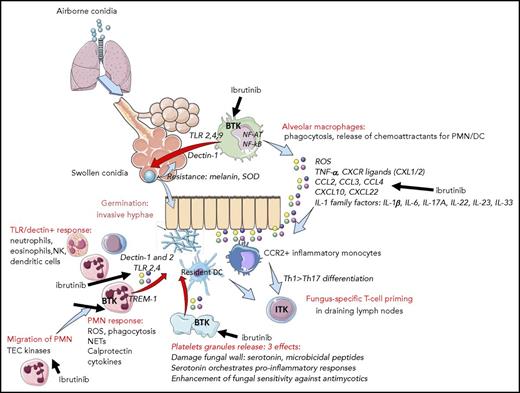

Ibrutinib may permit invasive fungal infections through multiple effects. These include inhibition of alveolar macrophage, neutrophil, T-cell, and platelet function as well as alterations in the chemoattractant and cytokine environment. DC, dendritic cells; NETs, neutrophils extra-cellular traps; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxyde dismutase; Th, T helper. See supplemental Figure 1 in the article by Ghez et al that begins on page 1955.

Ibrutinib may permit invasive fungal infections through multiple effects. These include inhibition of alveolar macrophage, neutrophil, T-cell, and platelet function as well as alterations in the chemoattractant and cytokine environment. DC, dendritic cells; NETs, neutrophils extra-cellular traps; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophils; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxyde dismutase; Th, T helper. See supplemental Figure 1 in the article by Ghez et al that begins on page 1955.

Also in this issue of Blood, O’Brien et al2 report a 5-year experience with ibrutinib which shows continued favorable outcomes and should increase enthusiasm for this agent, but as the associated commentary by Brown3 points out, it strengthens the need to understand early- and late-occurring toxicities. Through the extended follow-up and review of the non-trial experience, we are gaining additional knowledge regarding risks of ibrutinib, including some that were not recognized in the clinical trial population.

Ibrutinib is a disease-altering therapy for many B-cell malignancies that has been approved for 4 different cancers and chronic graft-versus-host disease. Ibrutinib is highly effective in all categories of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), the most prevalent adult leukemia, and is better tolerated than other available therapies. This has led to its widespread and increasing use.

However, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and other opportunistic fungal infections have recently been noted in small series and case reports on ibrutinib treated patients.4,5 This raises concern that ibrutinib may increase the risk for these infections because they are uncommon in CLL patients. Adding to the concern is an alarming observation from an ibrutinib combination study in primary central nervous system lymphoma that 39% of patients developed invasive aspergillosis.6

This information prompted Ghez et al to conduct a survey of centers in the French Innovative Leukemia Organization to identify patients who were diagnosed with invasive fungal infections while taking ibrutinib. They found a total of 33 cases: 27 aspergillosis, 4 disseminated cryptococcosis, 1 mucormycosis, and 1 pneumocystis pneumonia. Unsurprisingly, all but 3 of these cases were in CLL patients because CLL is likely to be the most common indication for prescribing ibrutinib. They report a high rate of central nervous system involvement in the patients with aspergillosis (11 of 27). This is consistent with a recently reported retrospective cohort study that found an incidence of 4.1% for opportunistic infections during ibrutinib treatment, and aspergillosis accounted for the majority, which adds to the mounting evidence that ibrutinib use is associated with these highly morbid infections.7

It is notable that the majority of patients in the French cohort had at least 1 additional factor that increased their risk for fungal infections. This included well-recognized risk factors such as chemotherapy within the last 6 months, neutropenia, and corticosteroid use. The implication was that use of ibrutinib alone may be insufficient to permit fungal infections so a second factor is necessary. This information can be used to identify which patients are at highest risk for this complication.

Interestingly, 85% of fungal infections occurred in the first 6 months after starting ibrutinib; 61% occurred in the first 3 months. This suggests that risk for invasive fungal infections may decrease with longer exposure to ibrutinib. It has previously been shown that infections decrease 6 months after the start of ibrutinib treatment concomitant with an increase in levels of immunoglobulin A.8 Perhaps the later developing immune effects of ibrutinib are less suppressive of the functions required for defense against invading fungi or they may strengthen these defenses. Whether these later immune effects are truly a global immune reconstitution or a more favorable form of immune dysregulation remains to be seen.

The mechanism by which ibrutinib permits fungal infections is of great interest. The main target of ibrutinib is BTK, which is important for the normal function of B cells.9 However, it is unlikely that inhibition of BTK in B cells alone accounts for this risk, because patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia who have a genetic deficiency of BTK do not commonly experience invasive fungal infections. It is more probable that inhibition of BTK in other cells within a mature immune system (such as macrophages) and inhibition of the other targets of ibrutinib play a role because ibrutinib inhibits several kinases important for immune function such as ITK and TEC.9,10 The potential for different mechanisms by which ibrutinib may allow establishment of an invading fungal organism into an infection are shown in the figure. It is important to determine whether fungal infections will also be observed with more selective BTK inhibitors such as acalabrutinib.

These findings by Ghez et al, in conjunction with other reports, establish an association between ibrutinib and invasive fungal infections. This leads to several important clinical questions such as which patients are best selected for ibrutinib treatment and who would benefit from prophylaxis. The overall incidence of these infections is low enough that routine prophylaxis for all patients with CLL who are taking single-agent ibrutinib would be excessive, especially given the cost and drug interactions with ibrutinib. However, prophylaxis is reasonable in select patients with additional risk factors. More work such as the 5-year follow-up by O’Brien et al2 will need to be done to better identify who might benefit from prophylaxis and to define the secondary factors that add to risk.

Clinicians need to stay vigilant for signs of aspergillosis and other fungal infections in their ibrutinib-treated patients so that these serious infections are rapidly diagnosed and treated. Although it is important to understand the risks of any therapy, ibrutinib remains the best option for treating the malignancies of many patients and, in most cases, risk for invasive fungal infections should not deter its use.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.