Abstract

Richter syndrome (RS) is the development of an aggressive lymphoma in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Two pathologic variants of RS are recognized: namely, the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) variant and the rare Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) variant. Histologic documentation is mandatory to diagnose RS. The clinical suspicion of RS should be based on clinical signs and symptoms. Differential diagnosis between CLL progression and RS and choice of the biopsy site may take advantage of positron emission tomography/computed tomography. Molecular lesions of regulators of proliferation (CDKN2A, NOTCH1, MYC) and apoptosis (TP53) overall associate with ∼90% of DLBCL-type RS, whereas the biology of the HL-type RS is largely unknown. The prognosis of the DLBCL-type RS is unfavorable; the outcome of HL-type RS appears to be better. The most important RS prognostic factor is the clonal relationship between the CLL and the aggressive lymphoma clones, with clonally unrelated RS having a better prognosis. Rituximab-containing combination chemotherapy for DLBCL is the most widely used treatment in DLBCL-type RS. Fit patients who respond to induction therapy should be offered stem cell transplantation (SCT) to prolong survival. Adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine is the preferred regimen for the HL-type RS, and SCT consolidation is less used in this condition.

Definition and morphology

Richter syndrome (RS) is defined as the occurrence of an aggressive lymphoma in patients with a previous or concomitant diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL). Two pathologic variants of RS are currently recognized, namely the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) variant and the Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) variant.1

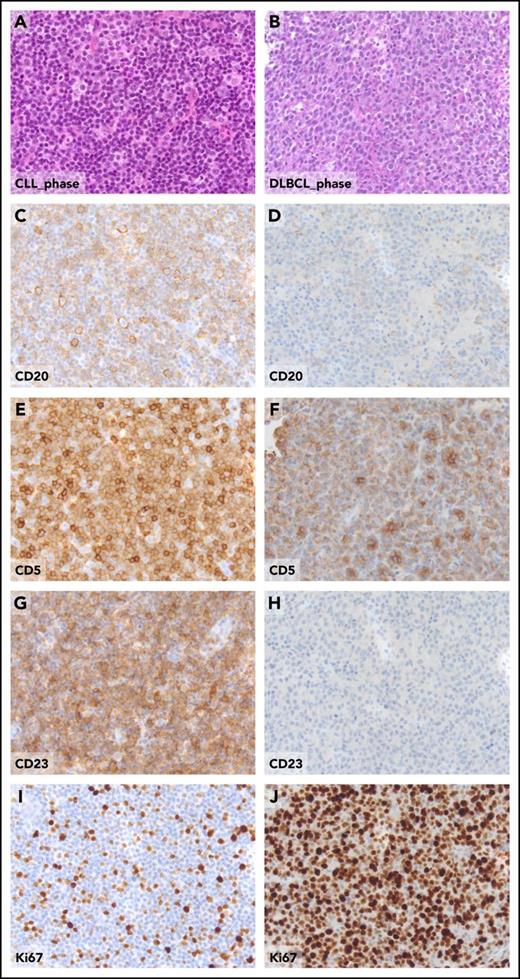

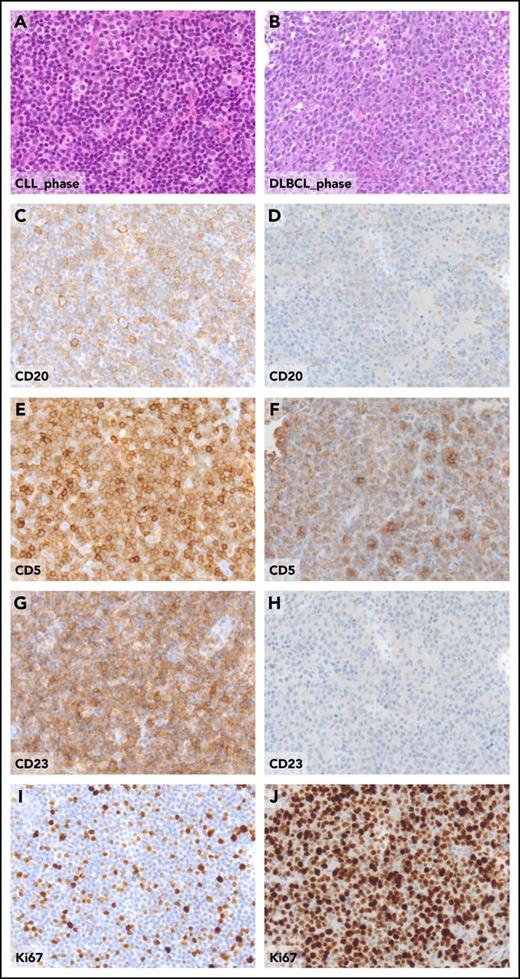

Morphologically, the DLBCL-type RS consists of confluent sheets of large neoplastic B lymphocytes (Figure 1) resembling either centroblasts (60%-80% of cases) or immunoblasts (20%-40% of cases).2-4 CLL transformation should be differentiated from histologically aggressive CLL. From a pathological standpoint, histologically aggressive CLL shows an increase in size and proliferative activity of the CLL cells, as well as expansion of the proliferation centers in the lymph nodes, which are broader than a 20 times field or become confluent and enriched of proliferating cells.1,5 Because the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues does not provide criteria supporting the differentiation between histologically aggressive CLL and DLBCL-type RS, such a distinction is based on the individual interpretation and expertise of the pathologist. Criteria for differentiating DLBCL-type RS from histologically aggressive CLL have been proposed,6 and include the occurrence of (1) large B cells with nuclear size equal or larger than macrophage nuclei or more than twice a normal lymphocyte and (2) a diffuse growth pattern of large cells (not just presence of small foci). By applying these criteria, up to 20% of cases diagnosed as DLBCL-type RS would be more appropriately classified as histologically aggressive CLL.6 In the lack of a shared and clear-cut definition of DLBCL-type RS, and given the rarity of this condition and the notion that DLBCL-type RS and aggressive CLL may look alike, we suggest revision of the diagnostic biopsy by an expert pathologist to avoid misclassifications that may impact on treatment choices and patient outcome. Phenotypically, DLBCL-type RS are CD20+, whereas CD5 is expressed in only a fraction (∼30%) of cases, and CD23 expression is even more rare (∼15% of cases) (Figure 1).2 Based on immunophenotypic markers, most DLBCL-type RS (90%-95%) have a post–germinal center phenotype (IRF4 positivity) whereas only 5% to 10% display a germinal center phenotype (CD10 expression).2 MYC is expressed by 30% to 40% of cases and its expression pairs with gene translocation.6 Similar to CLL, the DLBCL-type RS also frequently expresses BCL2. However, apart from occasional cases harboring BCL2 amplification, the BCL2 gene is rarely affected by genetic lesions that are instead common in de novo DLBCL, including translocations or somatic mutations.7 Although programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) is rarely expressed by CLL and de novo DLBCL, DLBCL-type RS harbors PD-1 expression in up to 80% of cases, which is a distinguishing feature of DLBCL-type RS compared with de novo DLBCL and may have implications for immunotherapy.8 The vast majority of DLBCL-type RS are Epstein-Barr virus negative (EBV−).2,4 Based on the analysis of immunoglobulin genes, most of the DLBCL-type RS (∼80%) are clonally related to the preceding CLL phase, thus representing true transformations.2,4 However, a fraction of RS cases display a rearrangement of immunoglobulin genes distinct from that of the CLL phase, documenting a clonally unrelated origin. From a pathologic standpoint, DLBCL-type RS developed after treatment with novel targeted agents does not differ from that developed after chemoimunotherapy.9

Pathologic aspects of the lymph node in the CLL phase and in the DLBCL phase from a patient who experienced clonally related RS transformation. Hematoxylin and eosin sections of CLL involved lymph node (A) and of DLBCL-type Richter transformation (B). The expression of CD20, CD5, CD23, and Ki67 detected by standard immunohistochemistry, the CLL-phase lymph node (C, E, G, I), and, for comparative purposes, in the DLBCL-type Richter transformation (D, F, H, J), are shown. Original magnification ×20 for all panels.

Pathologic aspects of the lymph node in the CLL phase and in the DLBCL phase from a patient who experienced clonally related RS transformation. Hematoxylin and eosin sections of CLL involved lymph node (A) and of DLBCL-type Richter transformation (B). The expression of CD20, CD5, CD23, and Ki67 detected by standard immunohistochemistry, the CLL-phase lymph node (C, E, G, I), and, for comparative purposes, in the DLBCL-type Richter transformation (D, F, H, J), are shown. Original magnification ×20 for all panels.

Diagnosis of the HL variant of RS requires classical Reed-Sternberg cells showing a CD30+/CD15+/CD20− phenotype in an appropriate polymorphous background of small T cells, epithelioid histiocytic, eosinophils, and plasma cells.10 The presence of Reed-Sternberg–like cells atypically expressing both CD30 and CD20 but lacking CD15 in the background of CLL does not qualify for the diagnosis of HL-type RS.10 The vast majority of cases of the HL-type RS are EBV+ and harbor distinct immunoglobulin rearrangements compared with the paired CLL, thus representing de novo, EBV-driven lymphomas arising in a CLL patient.10

Pathogenesis of DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

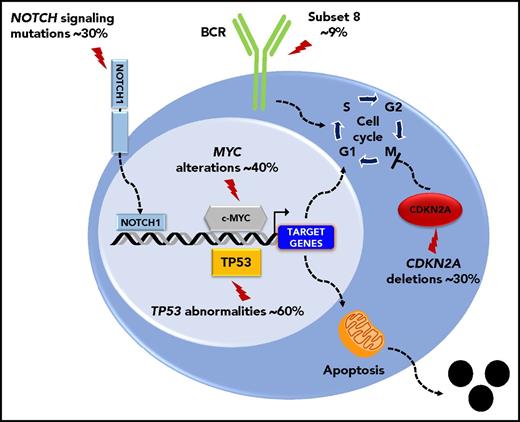

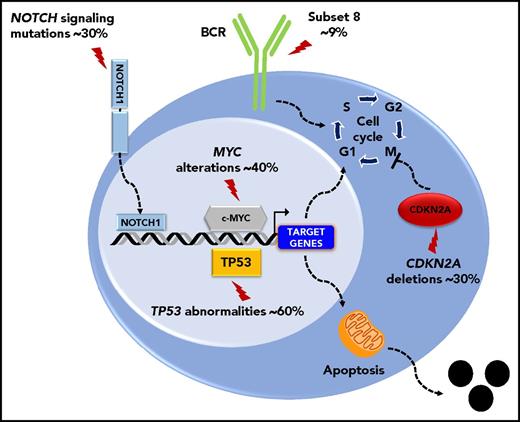

The molecular profile of the DLBCL-type RS is heterogeneous, lacks a unifying genetic lesion, and does not overlap with the genetics of de novo DLBCL. Indeed, transformed DLBCL-type RS lacks molecular lesions in signaling pathways and B-cell differentiation programs that are otherwise commonly targeted in de novo DLBCL. DLBCL-type RS lacks lesions common to all de novo DLBCL subtypes, such as inactivation of the acetyltransferase genes CREBBP/EP300 and of the B2M gene, as well as those common to non–germinal center DLBCL (eg, translocations of BCL6 and loss of PRDM and TNFAIP3) or germinal center DLBCL (eg, translocations of BCL2).7 These differences indicate that DLBCL transformed from CLL and de novo DLBCL represent distinct disease entities. Genetic lesions of DLBCL-type RS recurrently target the TP53, NOTCH1, MYC, and CDKN2A genes,4,7,11 indicating that DLBCL-type RS shares with other transformed lymphomas a common molecular signature characterized by lesions affecting regulators of apoptosis and proliferation.4,7,11 Deregulation of these programs conceivably accounts for the aggressive clinical phenotype of DLBCL-type RS that combines chemoresistance and fast progression. TP53 mutations occur in ∼60% to 80% DLBCL-type RS and are generally acquired at the time of transformation (Figure 2).4 Consistent with the central role of TP53 in mediating the antiproliferative effect of chemotherapies, its loss explains the chemorefractory phenotype typically shown by DLBCL-type RS. CDKN2A deletions occur in ∼30% of cases (Figure 2), and are generally acquired at the time of transformation.8,9 The MYC network is generally deregulated in ∼70% of DLBCL-type RS (Figure 2)4,12 by somatic structural alterations of MYC (∼30% of cases),4,7,11,13 by truncating mutations and deletions of the MYC− regulator MGA (∼10% of cases),12 and by mutations affecting MYC trans-regulatory factors as NOTCH1 (∼30% cases).14-16 Cell-cycle deregulation by CDKN2A deletion and MYC deregulation, which are often acquired at the time of transformation, may explain the progressive behavior of DLBCL-type RS.

Key molecular alterations of DLBCL-type RS. Genes and pathways that are molecularly deregulated are schematically represented. The prevalence of molecular alterations is reported beside each gene or pathway.

Key molecular alterations of DLBCL-type RS. Genes and pathways that are molecularly deregulated are schematically represented. The prevalence of molecular alterations is reported beside each gene or pathway.

Biased usage of stereotyped immunoglobulin genes in the subset 8 configuration (IGHV4-39/IGHD6-13/IGHJ5) characterizes a proportion of DLBCL-type RS, supporting a role of B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling in transformation (Figure 2).3 The strong and unlimited capacity of CLL harboring this BCR configuration to respond to multiple autoantigens and immune stimuli from the microenvironment may explain the particular aggressiveness of the CLL-harboring subset 8 BCR and their increased propensity to transform into RS.17 Among the various types of RS transformation, the biology of clonally unrelated RS significantly differs from those of clonally related cases. Indeed, the prevalence of TP53 disruption in clonally unrelated RS is low (∼20%) and is similar to de novo DLBCL. Also, stereotyped Immunoglobulin genes are frequent in clonally related DLBCL-type RS (∼50%), but virtually absent in clonally unrelated RS.

The genetics of RS developing after treatment with novel agents is largely unknown. In limited series, recurrent molecular features include complex karyotype, TP53 abnormalities and 8q24 abnormalities.10,18 BTK or PLCG2 mutations accounts for most of the ibrutinib-resistant CLL progression, while mutations of the BCR signaling are found only in ∼30% of RS that emerge after ibrutinib.18,19

Risk factors for development of DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

Biomarkers that have been reported as associated with risk of DLBCL-type RS development include the mutational status of NOTCH1, TP53 abnormalities,7,20,21 and the use of subset 8 immunoglobulin genes. In 2 institutional cohorts, CLL patients presenting with NOTCH1 mutations had a significantly higher cumulative probability of developing DLBCL-type RS compared with CLL without NOTCH1 mutations, though this observation was not validated in the CLL8 study cohort.20-23 CLL patients harboring immunoglobulin genes in the subset 8 configuration have a 24-fold increased risk or RS development.3 Presence of near-tetraploidy (4 copies of most chromosomes within a cell) and complex karyotype associate with RS development in ibrutinib-treated patients.24 Conversely, parameters reflecting CLL bulk are not generally considered to be a risk factor for RS development.25

Role of CLL treatment in the development of DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

The incidence rate of DLBCL-type RS does not significantly differ on whether the patient has been treated with chlorambucil, fludarabine, or fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (Table 1).26,27 The incidence of DLBCL-type RS seems to be lower in patients treated with rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide (FCR) when compared with patients treated with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) alone, suggesting a possible protective role of rituximab against RS, though the mechanism underlying this observation is not known.28 The longer latency associated with a deeper remission obtained with FCR may be an alternative explanation of the lower incidence of RS among FCR-treated CLL.

Changes in the treatment scenario of CLL might change the epidemiology, biology, and genetics of RS. Although the limited follow-up prevents definitive conclusions, the rate of transformation among relapsed/refractory CLL treated with ibrutinib, idelalisib, or venetoclax seems to be comparable to that of historical controls treated with chemotherapy/chemoimmunotherapy.29-36 Consistent with the lack of a specific contribution of novel agents to RS development, RS occurred at similar rates among relapsed CLL randomized to receive ibrutinib vs ofatumumab, idelalisib plus rituximab vs rituximab, and venetoclax plus rituximab vs bendamustine plus rituximab.30,37,38 RS typically occurs after a short time frame (generally within 1 year) from novel agent start, suggesting that some patients entered the treatment with preexisting hidden foci of RS.9

Although the type of therapy does not deeply affect the risk of RS development, the more heavily pretreated the disease, the higher the risk of RS.39

Approach to Richter syndrome diagnosis

The clinical suspicion of RS transformation should arise in CLL patients developing physical deterioration, fever in the absence of infection, rapid and discordant growth of localized lymph nodes, and/or sudden and excessive rise in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. The specificity of these clinical signs for RS transformation is only 50% to 60%. In the remaining cases, the histopathologic assessment can either show progressive CLL, aggressive CLL, or even solid cancer.40 In some cases, RS may arise in extranodal sites; an extranodal mass developing in a CLL patient should be included in the differential diagnosis.

In case there are clinical suspicions of transformation, the fluorodeoxyglucose (18FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) characteristics of the lesion, in particular the standardized uptake value (SUV [maximum SUV (SUVmax)]), may guide the choice of whether to perform a biopsy because sites affected by RS are expected to have SUVs overlapping with those of de novo DLBCL.40-42 Among CLL treated with chemotherapy plus or minus immunotherapy, a SUVmax >5 has a high sensitivity (91%) for detecting RS transformation, but it has low specificity (60%-80%) because it may also highlight lymph nodes with expanded proliferation centers, infections, or metastases of solid tumors. The main contribution of 18FDG PET/CT in RS diagnosis relies on its high (97%-98%) negative predictive value, meaning that in the presence of a negative 18FDG PET/CT, the final probability of RS transformation is only 2% to 3%.40-43 Consistently, if the 18FDG PET/CT is negative, biopsy can be avoided.

In the largest series of PET/CT prospectively performed in patients following kinase inhibitor discontinuation, a different SUVmax threshold (≥10) was assessed as an indicator of RS. Given the low positive (63%) and negative (50%) predictive value, PET/CT with SUVmax ≥10 did not turn out to be a useful noninvasive method to diagnose or rule out RS post–kinase inhibitor therapy. In the same study, 5 of 8 of the biopsies confirmed as RS showed a SUVmax ranging from 5 to 9, whereas only 3 of 8 RS had a SUVmax ≥10, further reinforcing the notion that a lower threshold (ie, SUVmax 5) should also be used in the setting of kinase inhibitor failure to rule our RS.44

Histologic documentation is mandatory to diagnose RS. An excision biopsy is considered the gold standard for RS diagnosis because samples obtained with fine-needle biopsy or aspiration may not be representative of the pathologic architecture of the tumor, especially in cases where the sheets of transformation are admixed to small cells. Furthermore, fine-needle biopsy of an enlarged proliferation center, which may be occasionally observed in lymph nodes of progressive or aggressive CLL, may give rise to false-positive misdiagnosis of RS transformation.45 Because RS is often restricted to 1 single lesion at transformation, any biopsy aimed at exploring whether RS has occurred should be directed at the index lesion (ie, the lesion displaying the most avid 18FDG uptake at PET/CT).

Prognosis of DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

The prognosis of DLBCL-type RS is generally poor. A validated RS prognostic score based on 5 adverse risk factors (Zubrod performance status >1, elevated LDH levels, platelet count ≤100 × 109/L, tumor size ≥5 cm, and >2 prior lines of therapy) stratifies 4 risk groups based on the number of presenting risk factors: 0 or 1, low risk (median survival, 13-45 months); 2, low-intermediate risk (median survival, 11-32 months); 3, high-intermediate risk (median survival, 4 months); 4 or 5, high risk (median survival, 1-4 months).46

The clonal relationship between the CLL and DLBCL clones is the most important prognostic factor, with a longer median survival (∼5 years) for patients with clonally unrelated DLBCL compared with clonally related DLBCL transformation (8-16 months).4,47 As a consequence, investigating the clonal relationship in DLBCL-type RS patients is clinically relevant, especially considering that clonally unrelated DLBCL may be managed as a de novo DLBCL arising in the context of CLL, rather than a true transformation.48

RS after ibrutinib or venetoclax is highly aggressive. In the largest series of CLL patients developing RS on novel agents, outcomes were generally poor for those who did not achieve remission, which overall accounts for only 13% of cases.9,35,49-51 Because the number of prior therapies is a risk factor in RS,46 the poor outcome of RS after novel agents may be a reflection that most of these patients have already been treated with multiple lines of previous therapy.

Treatment options for DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

RS is always an indication for treatment, and watch and wait is not an option. Patients who are unfit for an active treatment should be considered for palliation and hospice care.

Chemotherapy approaches

Chemotherapy regimens commonly used to treat aggressive and high-grade B-cell non-HLs have been investigated in DLBCL-type RS (Table 2). Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (R-CHOP) has shown a response rate of 67% (complete response [CR], 7%), with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 10 months and a median overall survival (OS) of 21 months.52 The treatment-related mortality of R-CHOP is low (3%), and hematotoxicity (65% of patients) and infections (28% of patients) are the most common adverse events of this regimen (Table 2).52 The substitution of rituximab with second-generation anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (ie, ofatumumab) within the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) schema does not improve response rate and survival when compared with historical cohorts treated with R-CHOP.53 Rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (R-EPOCH) results in a 37% response rate (CR 20% of patients) in DLBCL-type RS, median PFS of 3.5 months, and median OS of 5.9 months. Hospitalization because of neutropenic fever or infection complicates 22% of R-EPOCH cycles.43

Platinum-containing regimens have also been evaluated. The oxaliplatin, fludarabine, ara-C, and rituximab (OFAR) regimen has shown a response rate of 38% to 50% (CR, 6%-20%), though responses are of short duration (median PFS of 3 months and median OS of 6-8 months). Severe hematotoxicity occurs in 77% to 95% of cases, severe infection in 8% to 17%, and treatment-related mortality in 3% to 8% (Table 2).54,55 Dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (DHAP) or etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHAP) result in an overall response rate (ORR) of 43% with 25% CR, and an 8-month median OS. The main toxicity is myelosuppression with grade 4 neutropenia in 83% of patients, grade 4 thrombocytopenia in 82%, and grade 3/4 anemia in 72%. Infectious complications account for 43% of patients whereas 39% present fever of unknown origin.56

Treatments developed for highly aggressive lymphomas are severely toxic in DLBCL-type RS. A fractioned cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD) regimen induces a response in 41% (CR, 38%) of patients, and translates into a median OS of 10 months. Severe hematotoxicity occurs in all cases, producing infective complications in 50% of patients, which in turn result in a treatment-related mortality of 14% (Table 2).57 Combination of rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with methotrexate and ara-C results in a response rate of 43% (CR, 38%), and translates into a median OS of 8 months. This combination is highly toxic despite the growth factor prophylaxis (severe hematotoxicity in 100% of cases, severe infections in 39%, treatment-related mortality of 22%).58

Based on these results, and despite the limited level of evidence imposed by small sample size and phase 1-2 design of trials, R-CHOP or R-CHOP–like regimens (ie, R-EPOCH) are widely used as first-line option for the treatment of DLBCL-type RS because they provide a good balance between activity and toxicity compared with the other regimens.

Stem cell transplantation

Because the response duration with chemotherapy alone is short, both autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) have been proposed as postremission therapies in DLBCL-type RS. Nevertheless, most patients (85%-90%) with DLBCL-type RS are unfit or do not achieve adequate response to proceed to transplant.

The European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) has retrospectively investigated the role of both autologous and allogeneic SCT as postremission therapy in DLBCL-type RS (Table 3).59 By this analysis, allogeneic or autologous SCT may benefit a subset of patients. At 3 years, relapse-free survival is 27% after allogeneic SCT and 45% after autologous SCT. The nonrelapse mortality at 3 years is 26% after allogeneic SCT and 12% after autologous SCT. Survival at 3 years is 36% after allogeneic SCT and 59% after autologous SCT.59

SCT could be effective in DLBCL-type RS by 2 different therapeutic mechanisms: dose intensity delivered by high-dose cytotoxic therapy and, in the case of allogeneic SCT, graft-versus-tumor activity. An argument in favor of the high-dose principle in DLBCL-type RS is the efficacy of autologous SCT. Although there is no clear plateau in relapse-free survival among patients who undergo autologous SCT, only a subset of relapses is related to RS, whereas the remaining progressions are due to CLL, suggesting that autologous SCT may eradicate the RS component in many patients even though the underlying CLL may persist. The existence of a graft-versus-leukemia effect in RS might be suggested by the plateaus of the relapse-free survival among RS patients treated with reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT.59

Disease activity at SCT is the main factor influencing the posttransplant outcome. Indeed, patients who undergo SCT with a chemotherapy-sensitive disease have a superior survival compared with those who undergo transplantation with active and progressive disease. The major benefit of SCT is obtained in young patients (<60 years). Among patients receiving allogeneic SCT, those conditioned with a reduced-intensity regimen have the longest survival.59 Overall, these data suggest that both autologous SCT and reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT can be effective in young patients with transformed CLL as long as they enter transplant with chemosensitive disease.

Novel agents

Although phase 1/2 studies of novel agents show promising signals of single-agent activity in DLBCL-type RS, these results warrant further investigations.

CLL is addicted to Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) signaling through the BCR, and a proportion of RS shows biased usage of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements suggesting that BCR played a role at a certain timepoint of the transformed disease. Transient activity of ibrutinib has been anecdotally reported in DLBCL-type RS, including response in 3 of 4 patients (1 CR, 2 partial responses [PRs]). In these patients, the median duration of response was of 6 months (Table 2).60 Acalabrutinib is a highly selective BTK inhibitor having minimal off-target activity in early clinical studies. In the ACE-CL-001 phase 1/2 trial (NCT02029443), the ORR to acalabrutinib among DLBCL-type RS (n = 29, including relapsed and refractory cases) was 38%, the median PFS was 3 months, and the median duration of response was 5 months (Table 2).61

Venetoclax is a specific inhibitor of BCL2 that acts with a TP53-independent mechanism and is effective in high-risk CLL. In the M12-175 (NCT01328626) phase 1 study, a limited number (n = 7) of DLBCL-type RS were treated with escalating doses of venetoclax, achieving a response rate of 43% (no CRs) (Table 2).62

Selinexor is a selective inhibitor of nuclear export. Deregulation of the nucleocytoplasmic transport of proteins plays an important role in cancer and depends on the activity of export proteins, including Exportin 1 (XPO1). XPO1 is the nuclear exporter of several tumor suppressor proteins, including TP53. In a phase 1 study, selinexor showed a signal of activity in 40% of DLBCL-type RS patients (n = 6) who were refractory to the previous chemotherapy regimen (Table 2).63

DLBCL-type RS frequently occurs in the context of an exhausted immune system. T-cell exhaustion in CLL is driven, at least in part, by immune checkpoint deregulation, including expression of high levels of checkpoint inhibitory molecules, such as PD-1, on T cells, and expression of ligands for these molecules, including PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) and PD-L2, on RS cells.8 Pembrolizumab, an antibody that targets the PD-1 receptor, provides signals of activity in DLBCL-type RS, including response in 4 of 9 patients (MC1485 phase 2 trial; NCT02332980) (Table 2).64 Nivolumab is a human immunoglobulin G4 PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor antibody that blocks PD-1. A phase 2 clinical trial (NCT02420912) combining ibrutinib and nivolumab was designed upon the evidence that ibrutinib has shown a synergistic activity with checkpoint blockade in preclinical models. The preliminary results described encouraging activity of this doublet in treating RS, with 3 of 5 patients responding to the combination (3 PR).65 Preliminary data on the administration of chimeric antigen receptor T cells in the setting of RS report discouraging responses (2 disease progressions), but further studies are warranted.66,67

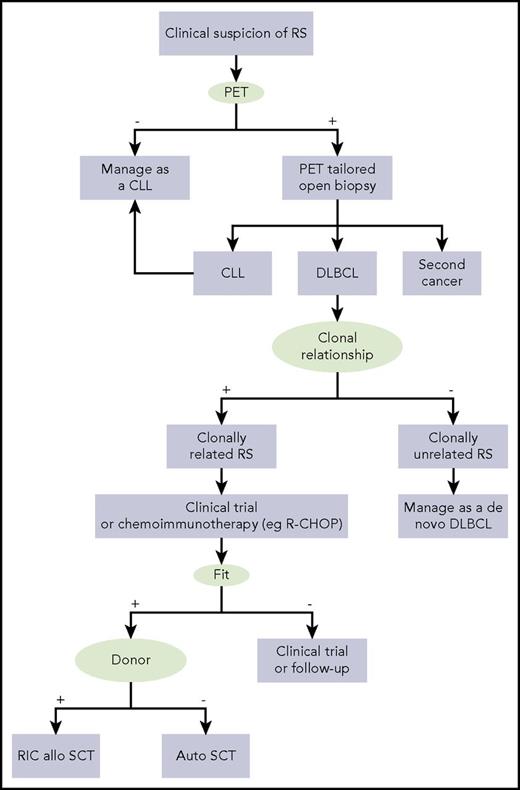

Suggested management of DLBCL-type Richter syndrome

Based on the available data, mostly derived from retrospective studies, it is difficult to propose a standard and optimized approach for DLBCL-type RS patients. However, some suggestions can be made (Figure 3): (1) in the event of a clinical suspicion of transformation because of the development of B symptoms, rapidly progressive lymph nodes >5 cm, especially if their growth is asymmetric, and/or LDH elevation, a 18FDG PET/CT should be performed and, if the SUVmax is ≥5, an excisional biopsy should be tailored to the index lesion with the highest SUVmax; (2) if the biopsy reveals an aggressive lymphoma, the clonal relationship with CLL should be assessed by comparing the immunoglobulin gene rearrangement of the CLL phase (which can be retrieved if previously tested during the CLL phase for prognostic purposes) with the immunoglobulin gene rearrangement of the RS phase (which can be analyzed on the RS diagnostic biopsy), although it may not be always feasible because of the lack of material or archival data of the CLL phase, or because of the formalin fixation of the RS biopsy, which might render the material inadequate for molecular studies; (3) if the CLL and DLBCL are clonally unrelated because of different immunoglobulin gene rearrangements, treat the disease as a de novo DLBCL because the DLBCL is a second malignancy (ie, R-CHOP as first line, reserving SCT only in the case of lack of response or relapse after R-CHOP); (4) if the CLL and DLBCL are clonally related because of the sharing of identical immunoglobulin gene rearrangements, it is a true transformation and the outcome is poor if the treatment follows the recommendations for de novo DLBCL. In the case of a true transformation, consider the patient for a clinical trial; if it is not available, the following approach can be considered: treat with chemoimmunotherapy (eg, R-CHOP) followed by consolidation with reduced-intensity conditioned allogeneic or autologous SCT depending on whether a donor is available and the patient is fit for transplant.

Hodgkin lymphoma–type Richter syndrome

HL-type RS is a rare disease. Indeed, according to the Mayo Clinic CLL Database, the 5-year and 10-year incidences of HL-type RS are 0.25% and 0.5%, respectively.68 No risk factors were found to be relevant for HL development in CLL patients. Given the disease rarity, clinical trials have never been performed to assess the treatment of HL-type RS and all of the information comes from retrospective analyses of single institutions or multicentric series. Doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) is the standard of care for de novo HL, and it is the most frequently used regimen for treating HL-type RS. Among HL-type RS treated with ABVD, the response rate ranges from 40% to 60% and the median OS is 4 years.68-71 Although the outcome of HL-type RS is significantly shorter than that of de novo HL, it appears to be longer than that observed in the DLBCL-type RS, consistent with the notion that, at variance from DLBCL-type RS, most HL-type RS are secondary tumors unrelated to the CLL. Therefore, SCT is less commonly used for consolidation of HL-type RS. Patients with relapsed HL-type RS can be treated similarly to patients with relapsed de novo HL (eg, salvage chemotherapy followed by autologous SCT, and possibly also with brentuximab).

Perspectives

Changes in the treatment scenario of CLL might also change the epidemiology of RS. The nongenotoxic mechanism of action of new drugs, their activity against TP53-mutated clones, from which most RS stem, and the better preserved immune function under these treatments, may result in a decrease of RS incidence rate if these agents are used as first-line therapy. Because the selective pressure imposed by treatment may shape the genetics of RS, the molecular pathogenesis of RS transformation occurring in patients treated solely with novel drugs may be different from that currently observed in RS patients who had been treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Drugs acting in a TP53-independent manner and targeting the molecular programs that are altered in RS, such as the apoptotic response (venetoclax) and BCR signaling (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib), or aiming at improving immune response against the transformed clones (immune checkpoint inhibitors, blinatumomab), may have promise in the management of RS and should be tested in combination with traditional chemoimmunotherapy approaches or with other novel agents. Consistently, ongoing clinical trials in RS are testing venetoclax combination with dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (NCT03054896), ibrutinib and obinutuzumab alone or in combination with CHOP (NCT03145480), pembrolizumab alone (NCT02576990) or in combination with ublituximab (NCT02535286), nivolumab in combination with ibrutinib (NCT02420912), and blinatumomab monotherapy (NCT03121534).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology 5 x 1000 no. 10007, Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro Foundation (Milan, Italy); Progetto Ricerca Finalizzata RF-2011-02349712, Ministero della Salute (Rome, Italy); Progetti di Ricerca di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) 2015ZMRFEA_004; Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (MIUR) (Rome, Italy); grant KFS-3746-08-2015, Swiss Cancer League (Bern, Switzerland); and grant 320030_169670/1, Swiss National Science Foundation (Bern, Switzerland).

Authorship

Contribution: D.R. and G.G. wrote the manuscript; and V.S. contributed to manuscript preparation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Davide Rossi, Division of Hematology, Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland, and Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, Institute of Oncology Research, Via Vela 6, 6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland; e-mail: davide.rossi@eoc.ch.