Whether additional Sex Combs-Like 1 (ASXL1) mutations are loss-of-function, dominant-negative, or gain-of-function mutations remains a point of considerable controversy. In this issue of Blood, Yang et al present clear evidence of a new “gain-of-function” role for an ASXL1 mutation.1

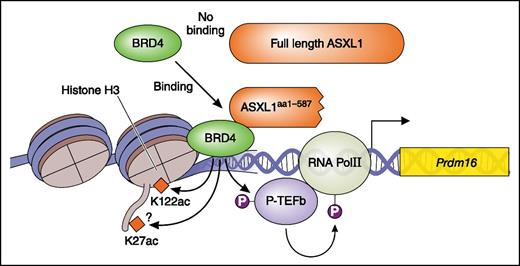

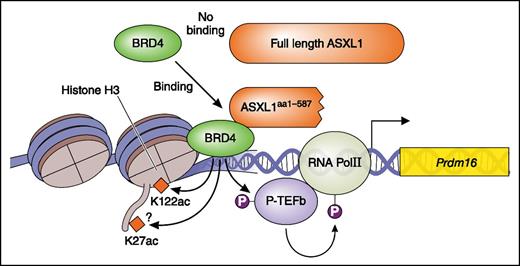

ASXL1 mutation is a gain-of-function mutation. The ASXL1 truncating mutant (ASXL1aa1-587) but not wt ASXL1 recruit BRD4. BRD4 acetylates H3K122 and activates pTEFb leading to phosphorylation (P; activation) of RNA pol II. This results in enhanced transcription. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

ASXL1 mutation is a gain-of-function mutation. The ASXL1 truncating mutant (ASXL1aa1-587) but not wt ASXL1 recruit BRD4. BRD4 acetylates H3K122 and activates pTEFb leading to phosphorylation (P; activation) of RNA pol II. This results in enhanced transcription. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Mutations of ASXL1 have been identified in a variety of myeloid neoplasms, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia or MDS-MPN, and chronic myeloid leukemia, and are uniformly associated with poor prognosis.2 It has been reported that knockdown or deletion of ASXL1 induces MDS-like symptoms, suggesting loss-of-function effects of ASXL1 mutations.3-5 However, most ASXL1 mutants that have been identified in myeloid malignancies harbor nonsense or frameshift mutations localized near the 5′ end of the last exon, which should thus escape nonsense-mediated decay of messenger RNA and produce a protein truncated at the C terminus. In addition, these mutations are always heterozygous, leaving 1 wild-type (WT) allele intact, implying either a dominant-negative or gain-of-function character.2

Inoue et al reported that the C-terminal truncating ASXL1 mutants induced an MDS-like disease in a mouse bone marrow transplant (BMT) model.6 They further showed that this C-terminal truncated ASXL1 protein was indeed expressed in MDS/AML cell lines harboring ASXL1 mutations.7 In light of these findings and other findings, it is now generally accepted that the ASXL1 mutations are dominant-negative or gain-of-function mutations. However, it remains unclear how the ASXL1 mutants produce dominant-negative effects, or what functions they gain through truncation. Dominant-negative effects of the truncating ASXL1 mutants are suggested based on the decreased methylation of histone H3K27 (H3K27me3) mediated by ASXL1/PRC2,7 but solid evidence supporting this notion is lacking. With respect to gain-of-function features of ASXL1 mutations, Balasubramani et al have reported that the ASXL1 mutant enhances the activity of BAP1, leading to deubiquitination of histone H2AK119 (H2AK119Ub)8 ; however, the full-length ASXL1 also enhances the BAP1 activity.9

In this issue, Yang et al present compelling new evidence that ASXL1aa1-587 acts as a gain-of-function mutant; a truncated mutant ASXL1 (ASXL1aa1-587) recruits BET bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) to genes, leading to the enhanced expression of genes including Fos and Prdm16 (see figure), something that full-length ASXL1 does not do. That is, Yang et al have shown that ASXL1aa1-587 (but not WT ASXL1) binds BRD4 and activates transcription of genes via phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II, presumably mediated by activation of the pTEFb complex and acetylation of H3K27/H3K122, both mediated by BRD4 (see figure). Using assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high throughput sequencing of cKit+ cells derived from a transgenic (Tg) mouse with Vav-1 promoter-driven expression of ASXL1aa1-587 in hematopoietic cells, they show that progenitors of the Tg mouse present a slightly relaxed chromatin conformation compared with that of normal progenitors. Consistent with this open chromatin status, there are more upregulated genes than downregulated genes in cKit+ cells of the Tg mouse. The upregulated genes include mainly hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and myeloid pathway-related genes. The authors focused on Prdm16 and Fos, which play important roles in HSCs, confirmed the upregulation of these genes by real-time polymerase chain reaction, and demonstrated that H3K122Ac and binding of BRD4 around the Prdm16 gene are increased in cKit+ cells in the Tg mouse. Additional studies using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing analysis will be needed to clarify whether transcription of the most upregulated genes in the Tg mouse are controlled in a similar way, via BRD4 and RNA polymerase II.

Overexpression of the truncated ASXL1 mutant induced MDS6 in a BMT model, whereas a locus knock-in (KI) mouse of a C-terminally truncated ASXL1 mutant showed no pathogenic effect at any stage.10 The Tg mouse described by Yang et al in contrast developed a variety of myeloid malignancies, including AML, MPN, MDS, and MDS/MPN. This discrepancy is likely due to the differences in the expression levels of the ASXL1 mutants in each model (that of the Tg model is approximately twofold that of the WT alleles), the length of each mutant (aa1-587 in the Tg model,1 aa1-643 in the BMT model,6 and aa1-643 plus 12 aa coded by the frameshifted sequence in the KI mouse model10 ), or the distinct expression patterns regulated by the promoters (respectively, Vav promoter; long terminal repeat of retrovirus vector; and the authentic ASXL1 promoter). Another significant difference in the phenotypes of the Tg and locus KI mice is that the numbers of HSCs and progenitors are increased in the former but not in the latter, as are the common myeloid progenitor/granulocyte-macrophage progenitor. Chimerism in competitive transplantation and the number of in vitro colony-forming unit cells are increased in the Tg model, but decreased in the locus KI mouse. Thus, as a model for clonal hematopoiesis or preleukemia, the locus KI mouse seems to be most appropriate. That notwithstanding, Yang’s work deserves recognition for showing the first evidence for gain-of-function features of the ASXL1 mutations, which are frequently observed in myeloid malignancies and are always associated with poor prognosis. In addition, the present finding that BRD4 plays important roles in ASXL1 mutant-induced pathogenesis is clinically important and may pave a way to establishing a new strategy in treating the ASXL1 mutant-related hematological malignancies, including usage of HDAC inhibitors and the BRD4-bromodomain inhibitor JQ1, which inhibits BRD4 binding to chromatin.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.