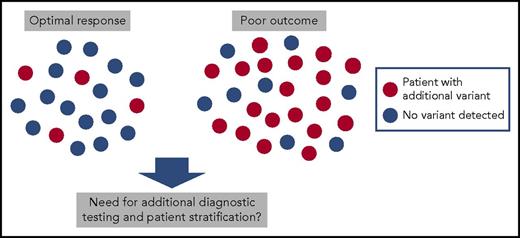

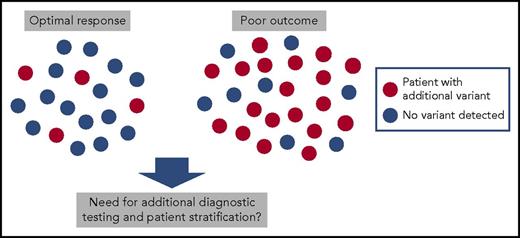

In this issue of Blood, Branford et al report that somatic variants other than BCR-ABL1 are frequently found in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).1 Notably, up to 70% of patients with a poor response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy with subsequent blast crisis had clinically relevant genetic variants, including somatic mutations, copy number variations, and novel fusion genes.

Chronic-phase CML patients at the diagnosis. Samples from 19 CML patients with optimal response to TKI therapy (achievement of major molecular remission) and from 27 patients with poor response (26 evolved to blast phase during TKI therapy and 1 patient was resistant to all TKIs) were sequenced with exome and RNA sequencing. Genetic variants in cancer genes involving somatic mutations, fusions, and copy number variations were common in patients with poor response.

Chronic-phase CML patients at the diagnosis. Samples from 19 CML patients with optimal response to TKI therapy (achievement of major molecular remission) and from 27 patients with poor response (26 evolved to blast phase during TKI therapy and 1 patient was resistant to all TKIs) were sequenced with exome and RNA sequencing. Genetic variants in cancer genes involving somatic mutations, fusions, and copy number variations were common in patients with poor response.

CML has been a model used to understand cancer development. Less than 60 years ago, the genetic abnormality, Philadelphia (Ph) translocation (translocation occurring between long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22), was described by Peter Nowell and David Hungerford. Since this discovery, targeted inhibition of the oncogenic BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase by small-molecule inhibitors (TKI) has profoundly changed the therapy of CML. Currently, the life expectancy of CML patients is close to that of the age-matched normal population.2 Further, the current goal of CML therapy is treatment-free remission and discontinuance of TKI therapy without relapse of the disease. However, a small proportion of patients fail to achieve optimal response to TKI therapy; in extreme cases, this will lead to full-blown acute leukemia-like disease with limited treatment options.3 Although many risk classifications exist (such as Sokal, Euro, and European Treatment and Outcome Study risk scores), chronic-phase CML patients are still treated with “one-size-fits-all” type of therapy starting usually with first-generation TKI imatinib. Interestingly, the disease evolution to blast crisis usually occurs within the first 2 years after diagnosis, suggesting that underlying disease biology in these poorly responding patients is different. If these patients could be identified at diagnosis, alternative treatment that would hopefully avert the subsequent blast crisis could be studied and developed.

To investigate the presence of additional genetic variants, Branford et al sequenced 46 chronic-phase CML patients at diagnosis with whole exome and RNA sequencing. They chose their cohort of patients from 2 extremes: 27 patients with a poor response to TKI therapy with 26 of these evolving to blast crisis, and 19 patients with an excellent response to TKI therapy with the achievement of a major molecular remission. Nineteen of 27 patients with poor response had clinically relevant variants occurring mostly in known cancer genes such as in ASXL1, IKZF1, RUNX1, and TP53 (see figure). Some of these mutations had clear associations with disease phenotypes such as IKZF1 alterations occurring in 5 of 6 patients developing lymphoid blast crisis. Similarly, of 7 patients with copy number variations at diagnosis, 5 evolved to blast phase and 1 had resistance to all 4 TKIs used in the treatment. Interestingly, novel Ph chromosome-associated gene rearrangements and fusions were also discovered, such as the BCR-NUP214-ABL1 transcript, and they were more common in patients with poor outcome.

In addition to sequencing performed in chronic phase, authors also analyzed 39 patients in blast crisis with paired samples from the chronic phase. All patients had variants in the cancer genes such as in IKZF1, RUNX1, ASXL1, BCORL1, and IDH1. In addition, known and novel gene fusions not associated with the Ph translocation were common (observed in 42% of blast phase patients).

Although this is the most comprehensive analysis of CML exomes thus far, there are still remaining questions needing study. What is the cause for blast crisis in patients who do not have additional variants at the diagnosis; could epigenetic alterations play a role or are blast phase initiating clones just so small that they were missed with the bulk sequencing, requiring single-cell methods to detect?4,5 Are the particular alterations such as the variants in IKZF1, RUNX1, and TP53 always a sign of poor prognosis? It should be noted that poor responder patients in this study do not resemble the typical chronic-phase CML cohort because blast phase is rare, with an incidence of only 1% to 2% per year in the first-line treatment. Furthermore, patients with suboptimal response, which is a much more common problem during current CML treatment, were not analyzed at all in this study. Some of the previous studies have shown that, for example RUNX1 alterations, are not always associated with poor outcome.6 It is also important to determine what kind of alternative treatment options can be offered for patients with poor prognosis variants if the screening for these alterations is to be added to the diagnostic workup. Perhaps allogeneic stem cell transplantation could be offered as a first-line treatment to these patients doomed to disease evolution with standard TKI therapy. Because most ongoing clinical studies in CML address the achievement of treatment-free remission, it would be of major interest to study whether some of the variants detected in good responding patients are not just mere innocent passengers but associated with the biology of the disease. Distinct variants could stratify a group of patients who cannot discontinue the current standard TKI therapy and would need alternative and/or combined treatment options to achieve this goal.

The authors conclude that, as genetic analyses become more and more affordable and available, it is important to gain a deeper understanding of the whole somatic genome in CML. Larger patient cohorts are needed, and similar studies have been ongoing with several other groups.6-10 Pooled analyses from various studies should address in the future whether additional genetic analyses could guide risk-adapted therapy and lead to a final cure of CML.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.