Key Points

Tissue factor and platelets are rate-limiting for mouse VT after inhibition of antithrombin and protein C.

Coagulation factor XII and circulating neutrophils are not rate-limiting in this animal model for VT.

Abstract

Tissue factor, coagulation factor XII, platelets, and neutrophils are implicated as important players in the pathophysiology of (experimental) venous thrombosis (VT). Their role became evident in mouse models in which surgical handlings were required to provoke VT. Combined inhibition of the natural anticoagulants antithrombin (Serpinc1) and protein C (Proc) using small interfering RNA without additional triggers also results in a venous thrombotic phenotype in mice, most notably with vessel occlusion in large veins of the head. VT is fatal but is fully rescued by thrombin inhibition. In the present study, we used this VT mouse model to investigate the involvement of tissue factor, coagulation factor XII, platelets, and neutrophils. Antibody-mediated inhibition of tissue factor reduced the clinical features of VT, the coagulopathy in the head, and fibrin deposition in the liver. In contrast, genetic deficiency in, and small interfering RNA–mediated depletion of, coagulation factor XII did not alter VT onset, severity, or thrombus morphology. Antibody-mediated depletion of platelets fully abrogated coagulopathy in the head and liver fibrin deposition. Although neutrophils were abundant in thrombotic lesions, depletion of circulating Ly6G-positive neutrophils did not affect onset, severity, thrombus morphology, or liver fibrin deposition. In conclusion, VT after inhibition of antithrombin and protein C is dependent on the presence of tissue factor and platelets but not on coagulation factor XII and circulating neutrophils. This study shows that distinct procoagulant pathways operate in mouse VT, dependent on the triggering stimulus.

Introduction

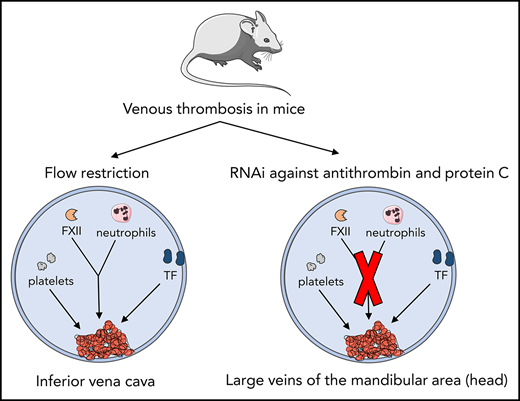

Venous thrombosis (VT) is a complex disease, and its pathogenesis is incompletely understood. Previously, it was proposed that cellular components of the blood contribute to the initiation and propagation of VT.1,2 In this respect, mouse models have been invaluable tools to study the pathogenesis of VT. In models based on flow restriction, induced by partial ligation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) in the absence of vascular and/or endothelial damage, it was shown that leukocytes were actively recruited to the inflamed venous vessel wall, resulting in initiation and propagation of VT.1-3 The “extrinsic” pathway of coagulation initiated by tissue factor (TF) exposure was a critical contributor to extensive fibrin formation, with monocyte-associated TF being an important TF source.2 In addition, the interplay between recruited blood cells (mainly platelets and neutrophils) and coagulation factor XII (FXII)-driven “intrinsic” coagulation seemed critical for thrombus formation in IVC models.

Although IVC mouse models proved valuable for identifying potential novel players in VT, the contribution of blood stasis, hypoxia, and endothelial activation to VT development may be overestimated compared with some human disease states,2,3 particularly where imbalanced coagulation is the driving factor for VT.4-6 It cannot be excluded that the numerous surgical handlings required to establish flow restriction in the IVC contribute to a proinflammatory state.

Our group described a mouse model of acute imbalance in coagulation, achieved by strong inhibition of hepatic expression of antithrombin (Serpinc1) and protein C (Proc) using synthetic small interfering (si) RNAs.7 Two to three days after siRNA injection, inhibition of natural anticoagulants resulted in a highly reproducible, siRNA dose–dependent, and thrombin-dependent thrombotic coagulopathy with no additional triggers; without interventions, it is fatal. Likely due to vascular bed–specific hemostasis and local flow characteristics,8 fibrin-layered thrombi were reproducibly formed in large veins in the head (masseter and mandibular area). Moreover, fibrin was deposited in the liver, and plasma fibrinogen was consumed, resulting in prolonged clotting times. Although the location of VT (in the head) limits quantitation of the thrombi, an attractive aspect of VT in this mouse model is that it follows inhibition of anticoagulant gene expression (achieved by IV siRNA injection) without any other handlings. This mouse model was used to further evaluate the role of TF, FXII, platelets, and neutrophils in the pathophysiology of VT.

Methods

Animal experiments

C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Maastricht, The Netherlands). Mice deficient in F12,9,10 F11,9,10 and Vwf11 were described earlier. F12- and F11-deficient mice were bred for over 9 generations to a C57BL/6J background and compared to in-house wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J controls bred parallel at the University Medical Center Hamburg animal facility, and shipped to the Leiden University Medical Center. Vwf−/− mice and their WT C57BL/6J controls were bred at the Leiden University Medical Center. All mice used were female and 6 weeks old (16-20 g). siRNAs targeting mouse antithrombin (siSerpinc1, catalog #S62673; Ambion, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), protein C (siProc, catalog #S72192), and a control siNEG (catalog #4404020) were used as previously described.7 siRNAs were complexed with Invivofectamine 2.0 or 3.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and injected IV (tail vein) at a dose of 5.75 or 1 mg/siRNA/kg body weight, respectively. siRNA complexes targeting F7 (catalog #4457292, sequences not provided by manufacturer) and F12 (sense: 5′-CACCUCUAGUUGUCCCUGAtt-3′ and antisense: 5′-UCAGGGACAACUAGAGGUGca-3′; catalog #S81736) were injected 24 hours before siSerpinc1/siProc treatment.

To block TF, 3 hours after siRNA injection, the rat monoclonal targeting mouse TF antibody 1H112 (Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) was injected intraperitoneally (20 mg/kg). A rat monoclonal antibody targeting human GP120 (20 mg/kg; Genentech) served as control. For platelet depletion, a rat monoclonal antibody against mouse GP1b (#R300; Emfret, Würzburg, Germany) was used. Depletion of neutrophils was achieved by using a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) and a rat isotype control immunoglobulin G (IgG) (clone RTK2758; BioLegend) as a control. Platelet and neutrophil antibodies were injected IV (5 mg/kg).

Liver and blood analyses

Liver transcript levels of Serpinc1, Proc, and F12 (F12 forward primer: AATCCGTGCCTTAATGGGGG; reverse primer: TCATAGCAGGTCGCCCAAAG) were determined by using quantitative polymerase chain reaction, with Actb as the housekeeping gene.7,13,14 Liver fibrin deposition and plasma FXII were determined by immunoblotting using the monoclonal antibody 59D814 and anti-FXII polyclonal antibody,15 respectively.

1H1 activity in mouse plasma was determined by using a homogenate of cultured TF-positive mouse smooth muscle cells and thrombin generation (TG) analysis. TG,16 ex vivo platelet activity,17 and plasma nucleosome levels18 were determined as previously described. Platelet and neutrophil numbers were determined with a veterinary hematology analyzer (Sysmex XE-2100; Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan). Blood neutrophil numbers were measured according to flow cytometry (LSR II; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using αLy6G-phycoerythrobilin (clone 1A8; BioLegend).

Phenotype assessment

VT after siSerpinc1/siProc injection has been previously described.7 Mice were euthanized 2 to 3 days after siSerpinc1/siProc injection.

After euthanization, formalin-fixed heads were decalcified (in 20% formic acid), dehydrated, paraffin embedded, and sectioned. After analysis of coronal serial sections of the head and neck, sections (4 μm) were made starting directly caudal of the eyes, because this area was most clearly and reproducibly affected, and thrombi in large veins were found here (in siSerpinc1/siProc–injected mice). Sections were stained by using hematoxylin and eosin or according to the Carstairs’ method.19 Severity was scored, and thrombi in the selected sections were categorized (a detail explanation is given in supplemental Figures 2 and 4, available on the Blood Web site). Scoring of VT severity and typing is descriptive (not quantitative).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded sections were stained with a rat monoclonal anti-mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8; BioLegend). For detection, horseradish peroxidase–labeled rabbit anti-rat IgG was used (Dako, an Agilent Technologies Company, Glostrup, Denmark). Horseradish peroxidase activity was imaged by using diaminobenzidine (Dako).

Results

TF-induced coagulation is rate-limiting for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C

Previously,7 we showed that VT upon silencing of the anticoagulant genes Serpinc1 and Proc using siRNA (siSerpinc1/siProc) is characterized by the presence of fibrin-layered (occlusive) thrombi in the large veins of the masseter and mandibular area of the head and the presence of (secondary) hemorrhages in these areas. Complete rescue was achieved by thrombin inhibition. First, we investigated whether thrombin and fibrin formation in this VT is dependent on the TF/extrinsic pathway.20 siRNA was used to deplete coagulation factor VII (FVII), which mediates TF-triggered procoagulant activity. Mice were treated with a FVII-specific siRNA (siF7, n = 10) or control siNEG (n = 10). Similar to previous observations,7 control mice treated with siNEG and siSerpinc1/siProc within 3 days developed the typical clinical features that coincide with VT in this model. They developed unilateral lesions around the eye and swellings in the head; in addition, they became lethargic, unresponsive to stimuli, hypothermic, and lost body weight. Although reduction of plasma FVII was strong (median of remaining FVII: 4.7% [range: minimum 2.3, maximum 12.0]), compared with siNEG (100%; P < .001), siF7 mice were not protected from VT (4 of 10 siNEG mice vs 7 of 10 siF7 mice presented with clinical signs 2 days after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment; P = .37); they also had comparable liver fibrin deposition (28.7 ng/mg [10.0, 74.6] vs 17.0 ng/mg [6.1, 118.8]; P = .09).

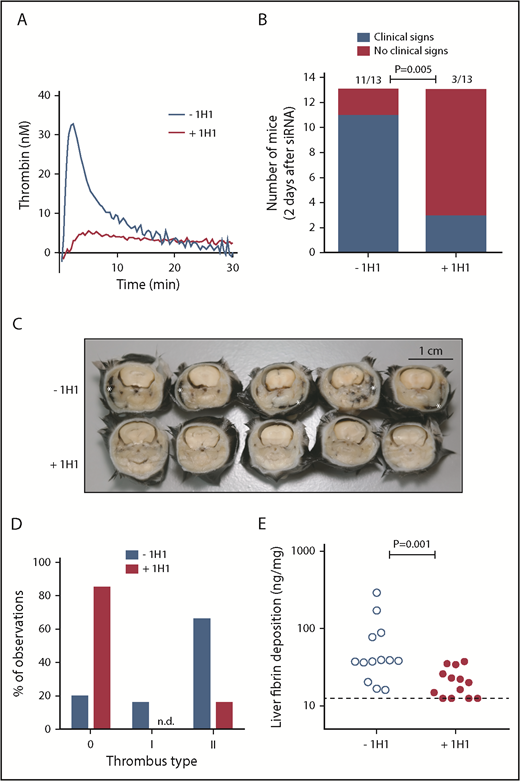

Because ∼5% of residual FVII levels may be sufficient to allow normal coagulation via the TF pathway, we treated mice with the 1H1 antibody, which specifically blocks mouse TF.12,21-23 Injection of 1H1 (+1H1) resulted in strong inhibition of mouse TF-induced plasma TG, compared with plasma from mice treated with a control antibody (–1H1) (Figure 1A). A small pilot study, in which mice received a single injection of 1H1 or control antibody 3 hours after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, found that 36 hours after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, +1H1 mice retained their normal health (n = 3), whereas those in the −1H1 group developed clinical signs of VT. However, at the time of actual euthanization (44 hours after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment), 1 mouse from the +1H1 group exhibited the clinical phenotype, suggesting that a single 1H1 dose was insufficient for effective and sustained TF neutralization throughout the experimental period.

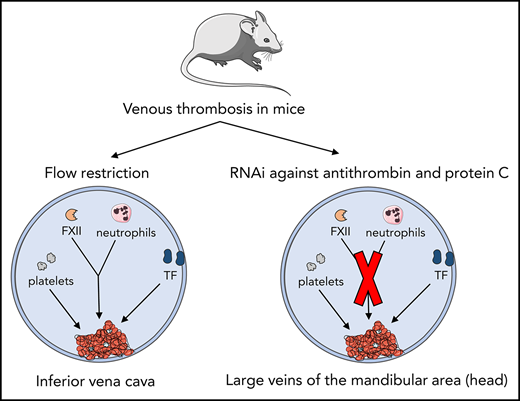

TF-induced coagulation is rate-limiting for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation initiated by TF-positive cell extract (mouse smooth muscle cells). In a parallel group of mice (n = 3), control antibody or 1H1 was injected intraperitoneal (no siRNA treatment). Forty-one hours after antibody treatment, mice were euthanized, and citrated blood was collected via the vena cava. Platelet-poor plasma was used for thrombin generation analysis. Curves represent the average of 3 mice treated with either control antibody (–1H1) or 1H1 antibody (+1H1). (B) Clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc, treated with control antibody or 1H1. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. Of note, results from experiment 1 (–1H1: 3 of 3 mice affected vs +1H1: 1 of 3 mice affected) and experiment 2 (–1H1: 8 of 10 mice affected vs +1H1: 2 of 10 mice affected; P = .02) were pooled. (C) Representative cross-sections of the whole head of mice (formalin-fixed and decalcified) from the –1H1 and the +1H1 groups (n = 5). Cross-sections were taken behind the eye and show the presence of macroscopically visible coagulopathy in and around the mandibular area (white asterisks). In this area, coagulopathy was visible for 11 of 13 −1H1 mice and 3 of 13 +1H1 mice. All mice were treated with siSerpinc1/siProc. The black bar represents 1 cm. (D) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering (see Methods section and supplemental Figure 4). Blue bars: −1H1 (n = 26); red bars: +1H1 (n = 26). Of note, results from experiment 1 (n = 6) and experiment 2 (n = 20) were pooled. (E) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in −1H1 (open circles) and +1H1 (filled circles) mice. P = .001. Of note, for the second 1H1 experiment (n = 10) liver fibrin deposition: −1H1: 37.4 ng/mg (16.1, 289.8) and +1H1: 15.6 ng/mg (12.5, 25.9); P = .003. Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Dashed line indicates the detection limit of 12.5 ng/mg. Fibrin deposition levels for C57BL/6J female mice (n = 6), treated with 1H1 or control antibody only, were below the detection limit (<12.5 ng/mg).

TF-induced coagulation is rate-limiting for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation initiated by TF-positive cell extract (mouse smooth muscle cells). In a parallel group of mice (n = 3), control antibody or 1H1 was injected intraperitoneal (no siRNA treatment). Forty-one hours after antibody treatment, mice were euthanized, and citrated blood was collected via the vena cava. Platelet-poor plasma was used for thrombin generation analysis. Curves represent the average of 3 mice treated with either control antibody (–1H1) or 1H1 antibody (+1H1). (B) Clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc, treated with control antibody or 1H1. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. Of note, results from experiment 1 (–1H1: 3 of 3 mice affected vs +1H1: 1 of 3 mice affected) and experiment 2 (–1H1: 8 of 10 mice affected vs +1H1: 2 of 10 mice affected; P = .02) were pooled. (C) Representative cross-sections of the whole head of mice (formalin-fixed and decalcified) from the –1H1 and the +1H1 groups (n = 5). Cross-sections were taken behind the eye and show the presence of macroscopically visible coagulopathy in and around the mandibular area (white asterisks). In this area, coagulopathy was visible for 11 of 13 −1H1 mice and 3 of 13 +1H1 mice. All mice were treated with siSerpinc1/siProc. The black bar represents 1 cm. (D) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering (see Methods section and supplemental Figure 4). Blue bars: −1H1 (n = 26); red bars: +1H1 (n = 26). Of note, results from experiment 1 (n = 6) and experiment 2 (n = 20) were pooled. (E) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in −1H1 (open circles) and +1H1 (filled circles) mice. P = .001. Of note, for the second 1H1 experiment (n = 10) liver fibrin deposition: −1H1: 37.4 ng/mg (16.1, 289.8) and +1H1: 15.6 ng/mg (12.5, 25.9); P = .003. Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Dashed line indicates the detection limit of 12.5 ng/mg. Fibrin deposition levels for C57BL/6J female mice (n = 6), treated with 1H1 or control antibody only, were below the detection limit (<12.5 ng/mg).

In the larger, second experiment (n = 10), 1H1 and control antibody injections were repeated 27 hours after the first antibody injection (30 hours after siSerpinc1/siProc injection). The 1H1 antibody provided protection from VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C (2 of 10 mice affected), compared with the control antibody-treated group (8 of 10 mice affected; P = .02; 11 of 13 vs 3 of 13, P = .005, when data are combined from 2 experiments) (Figure 1B). In addition, 1H1 treatment significantly interfered with body weight loss, which emphasizes retained health (−1H1: −0.8 g [–2.3, −0.4] and +1H1: 0.3 g [–1.1, 1.2]; P < .001, n = 13) (supplemental Figure 1A).

Cross-sections of the whole head taken behind the eye confirmed the presence of coagulopathy, which was macroscopically visible, notably in and around the mandibular area (–1H1: 11 of 13; +1H1: 3 of 13; P = .005) (Figure 1B-C). On a microscopic level, in the siSerpinc1/siProc −1H1 group, thrombi were found in larger and smaller veins of the head in all 13 mice. Moreover, extensive multifocal erythrocyte extravasations (hemorrhages) were present, particularly in the masseter and mandibular area, with associated subcutaneous edema. In contrast, in the siSerpinc1/siProc +1H1 mice, fewer thrombi or notable injuries were observed (4 of 13 mice) (supplemental Figures 2 and 3A). When the thrombosis presence was typed (descriptive, not quantitative analysis), both organized (type I) and unorganized (II) thrombi were found based on their composition and structure (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 4). In addition, liver fibrin deposition was significantly reduced (38.2 ng/mg [16.1, 289.8] vs 20.0 ng/mg [12.5, 25.0]; P = .001, n = 13) (Figure 1E).

FXII is not crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C

To study the role of the FXII/intrinsic pathway of coagulation20 in VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C, mice genetically deficient in FXII (F12−/−) were injected with siSerpinc1/siProc. WT mice were included as controls. Upon euthanization, liver transcript analysis confirmed the absence of F12 in F12−/− mice (F12 messenger RNA not detectable; P < .001, n = 11). Ellagic acid–induced TG in plasma derived from F12−/− mice (not treated with siSerpinc1/siProc) confirmed the defective contact activation-driven coagulation, whereas TF-induced TG was similar to that in WT mice (Figure 2A).

FXII is not crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation peak heights. Thrombin generation was induced by 20 μg/mL ellagic acid (EA; left graph) or 1 pM TF (right graph) in plasma from WT mice (open circles) or F12-deficient mice (F12−/−; filled circles). Significance was determined by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Clinical phenotype in WT and F12−/− mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test. (C) Representative coronal head section stained by using the Carstairs’ method of a normal WT mouse (no siRNA treatment). (D-E) Representative coronal head sections of WT and F12−/− mice stained by using the Carstairs’ method. Both mice developed siSerpinc1/siProc–associated thrombotic coagulopathy. Black bars represent 2000 µm. (F) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: WT (n = 21); red bars: F12−/− (n = 22). (G) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in the control group (WT; open circles) and the F12−/− group (F12−/−; filled circles). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in a pool of uninjected WT, F12−/−, and F11−/− C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 5.9 ng/mg [3.8, 10.2], n = 8).

FXII is not crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation peak heights. Thrombin generation was induced by 20 μg/mL ellagic acid (EA; left graph) or 1 pM TF (right graph) in plasma from WT mice (open circles) or F12-deficient mice (F12−/−; filled circles). Significance was determined by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Clinical phenotype in WT and F12−/− mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test. (C) Representative coronal head section stained by using the Carstairs’ method of a normal WT mouse (no siRNA treatment). (D-E) Representative coronal head sections of WT and F12−/− mice stained by using the Carstairs’ method. Both mice developed siSerpinc1/siProc–associated thrombotic coagulopathy. Black bars represent 2000 µm. (F) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: WT (n = 21); red bars: F12−/− (n = 22). (G) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in the control group (WT; open circles) and the F12−/− group (F12−/−; filled circles). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in a pool of uninjected WT, F12−/−, and F11−/− C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 5.9 ng/mg [3.8, 10.2], n = 8).

Two days after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, both WT and F12−/− mice showed the thrombotic coagulopathy associated with VT (9 of 11 vs 9 of 11 mice affected; P = 1.0) (Figure 2B). Coagulopathy was associated with weight loss in both groups (−2.0 g [–3.1, −1.3] vs −1.9 g [–2.5, −0.8]; P = .274) (supplemental Figure 1B). In addition, an siRNA was used to target F12 messenger RNA in VT (siF12). siF12-treated WT mice (not siSerpinc1/siProc treated) exhibited defective ellagic acid–induced TG but normal TF-induced TG (peak height: 52.0 nM thrombin [37.9, 62.4] vs 48.3 nM thrombin [40.9, 66.1]; P = .22). Upon siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, siF12-treated mice exhibited development of VT similar to the control siNEG group (7 of 8 vs 8 of 8 mice affected; P = 1.0).

Upon euthanization, the heads of the WT and F12−/− mice were sectioned and analyzed for thrombus formation and severity of the siSerpinc1/siProc–associated thrombotic coagulopathy. No differences in the severity of the coagulopathy and in the structure and lining of the thrombi were found (Figure 2C-F; supplemental Figure 3B). Although clinical and microscopic VT in the heads was unaffected, liver fibrin deposition was significantly lower for siSerpinc1/siProc–treated F12−/− mice compared with the WT mice (812.8 ng/mg [290.9, 2264] vs 339.9 ng/mg [133.3, 707.1]; P = .001) (Figure 2G).

Activated FXII drives coagulation by the intrinsic pathway via its substrate coagulation factor XI (FXI). We therefore subjected mice deficient in FXI (F11−/−) to siSerpinc1/siProc treatment. However, despite the tendency for delayed VT onset, as reflected in body weight loss (–2.0 g [–3.1, −1.3] vs −1.1g [–2.1, −1.0]; P = .001), F11−/− mice were not protected from VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C (9 of 11 vs 5 of 11 mice affected, 2 days after Serpinc1/siProc injection; P = .103) (supplemental Figure 5A). Histology of the heads of thrombotic F11−/− and WT control mice yielded a similar thrombotic coagulopathy in the mandibular area (supplemental Figure 5B-C), whereas liver fibrin deposition was not significantly altered (812.8 ng/mg [290.9, 2264] vs 731 ng/mg [157.4, 2019]; P = .267) (supplemental Figure 5D).

Platelets are crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C

Apart from the abundant presence of platelets in the thrombi in the head (supplemental Figure 6A), platelet numbers were reduced in the circulation upon VT development and liver fibrin deposition (supplemental Figure 6B). Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the circulating platelets did not display a significant increase in surface activation markers before the onset of VT (supplemental Figure 6C). To investigate the role of platelets during siSerpinc1/siProc–induced VT, platelets were depleted by using an antibody that targets mouse GP1b. Successful plate-let depletion from the circulation (no platelets detectable in blood) was confirmed in a dedicated pilot study (data not shown) and in a parallel group of mice that did not receive siSerpinc1/siProc (616 × 109 platelets/L [554, 642] vs 0 × 109 platelets/L [0, 7]; P = .036) (Figure 3A).

Platelets are crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood platelet numbers in mice not receiving siRNAs 3 days after injection with saline (–αGP1b; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse GP1b (+αGP1b; filled circles). P = .036, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical coagulopathy (blue bar) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice from the –αGP1b group died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Representative thrombus in a vein in the mandibular area in the control group (–αGP1b, panel C) and a representative vein in the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b, panel D) in the hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. thr, thrombus, with typical fibrin layers; rbc, postmortem clotted blood, rich in red blood cells; mus, striated muscle tissue. White bars represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 7 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombus categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αGP1b (n = 10); red bar: +αGP1b (n = 16). n.d., not detected. (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b) and the control group (–αGP1b). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines represent fibrin levels found in siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).

Platelets are crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood platelet numbers in mice not receiving siRNAs 3 days after injection with saline (–αGP1b; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse GP1b (+αGP1b; filled circles). P = .036, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical coagulopathy (blue bar) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice from the –αGP1b group died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Representative thrombus in a vein in the mandibular area in the control group (–αGP1b, panel C) and a representative vein in the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b, panel D) in the hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. thr, thrombus, with typical fibrin layers; rbc, postmortem clotted blood, rich in red blood cells; mus, striated muscle tissue. White bars represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 7 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombus categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αGP1b (n = 10); red bar: +αGP1b (n = 16). n.d., not detected. (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b) and the control group (–αGP1b). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines represent fibrin levels found in siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).

Control mice treated with siSerpinc1/siProc and subsequently injected with saline (–αGP1b) developed VT (6 of 7 mice affected) (Figure 3B). One of the affected mice died before it could be included for further analysis. In contrast, siSerpinc1/siProc +αGP1b mice (+αGP1b) appeared fully healthy (0 of 8 mice affected) and did not experience weight loss compared with the siSerpinc1/siProc –αGP1b group (−2.1 g [–3.1, 0.2] vs 0.1 g [–1.0, 0.8]; P = .043) (supplemental Figure 1C). Strikingly, αGP1b-mediated platelet depletion of siSerpinc1/siProc–treated mice when the first 2 mice presented the clinical features of the thrombotic phenotype also fully rescued mice from VT. In this experiment, all mice in the reference group were affected (9 of 9 vs 2 of 9 mice affected, –αGP1b and +αGP1b, respectively; P = .002). Of note, whereas platelet depletion fully rescued from VT, deficiency in von Willebrand factor (Vwf−/− mice), a protein critically involved in platelet adhesion and aggregation, did not confer protection from VT (4 of 6 Vwf−/− mice vs 5 of 6 Vwf+/+ mice affected 72 hours after siRNA injection).

In the siSerpinc1/siProc –αGP1b mice, thrombi and severe coagulopathy were identified (Figure 3C,E; supplemental Figure 3C). Remarkably, the mouse that was not clinically affected (–αGP1b) (Figure 3B) had thrombi in a venous vessel in the investigated coronal section of the head. In contrast, in the siSerpinc1/siProc +αGP1b mice, no thrombi or notable injuries were observed (Figure 3D-E). In line with these observations, liver fibrin deposition was significantly reduced in the siSerpinc1/siProc +αGP1b group (75.7 ng/mg [21.4, 143.9] vs 9.5 ng/mg [6.3, 21.7]; P = .001) (Figure 3F), although fibrin levels were above background levels (as determined in control mice injected with siNEG, (4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]; P < .001).

Circulating neutrophils are not rate-limiting for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C

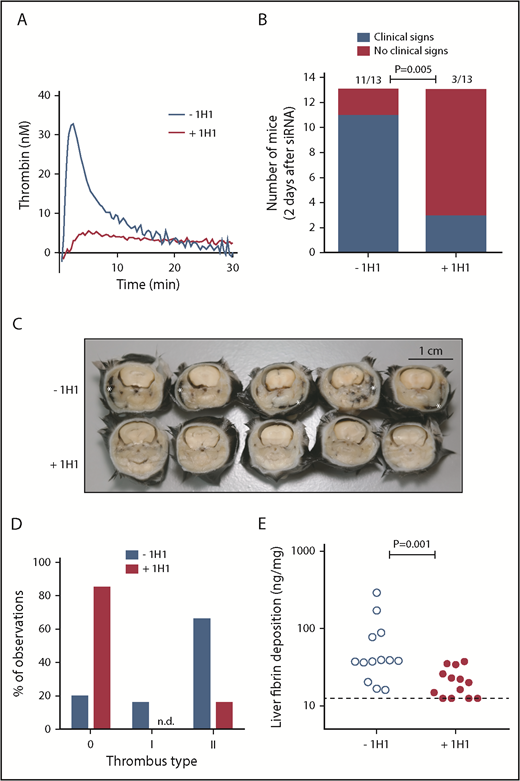

Mice were depleted of neutrophils 6 hours after siSerpinc1/siProc injection by using an antibody targeting mouse neutrophil-specific Ly6G (+αLy6G). An isotype IgG antibody was used in the control group (–αLy6G). In a dedicated experiment, flow cytometry analysis confirmed that the Ly6G-positive cells were fully absent from the circulation up to 4 days after antibody injection (data not shown). Using the same approach, we again detected no neutrophils in the circulation of the siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G group 1 day after antibody injection (ie, 1 day before onset of VT) (supplemental Figure 8). In addition, neutrophil absence was confirmed in the siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G treated group after euthanization (720 neutrophils/μL [320, 1120] vs 0 neutrophils/μL [0, 280]; P < .001) (Figure 4A).

Circulating neutrophils are not a major mediator of VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood neutrophils levels in mice 3 days after injection with a rat IgG control (–αLy6G; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse Ly6G (+αLy6G; filled circles). P < .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice in both groups (–αLy6G and +αLy6G) died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .317, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Ly6G staining of thrombi found in sections of the head. Ly6G staining visualizes neutrophils, which are seen as brown-colored cells in the figures. Representative sections are shown for the –αLy6G (panel C) and +αLy6G groups (panel D). Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Black lines represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 9 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αLy6G (n = 22); red bars: +αLy6G (n = 20). (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the control group (–αLy6G) and the neutrophil-depleted group (+αLy6G). P = .931, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in solely siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).

Circulating neutrophils are not a major mediator of VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood neutrophils levels in mice 3 days after injection with a rat IgG control (–αLy6G; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse Ly6G (+αLy6G; filled circles). P < .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice in both groups (–αLy6G and +αLy6G) died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .317, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Ly6G staining of thrombi found in sections of the head. Ly6G staining visualizes neutrophils, which are seen as brown-colored cells in the figures. Representative sections are shown for the –αLy6G (panel C) and +αLy6G groups (panel D). Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Black lines represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 9 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αLy6G (n = 22); red bars: +αLy6G (n = 20). (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the control group (–αLy6G) and the neutrophil-depleted group (+αLy6G). P = .931, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in solely siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).

siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G and siSerpinc1/siProc –αLy6G mice both developed VT (8 of 12 mice vs 11 of 12 mice affected; P = .317) (Figure 4B). In addition, in both groups, body weight was decreased to a similar extent (−0.9 g [–3.2, 0.1] vs −2.5 g [–3.6, −0.3]; P = .132) (supplemental Figure 1D). On a microscopic level, sections of the heads were analyzed, and in both groups, thrombi were found in large veins, as well as hemorrhages and edema. Severity scoring yielded no differences (supplemental Figure 3D). In the siSerpinc1/siProc –αLy6G group, Ly6G-positive cells were abundantly present in thrombi, followed the alignment of structures identified as fibrin, and adhered to the thrombotic venous vessel wall (Figure 4C). Ly6G-positive cells were absent in the thrombi of the siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G group (apart from some weakly staining cells that were still observed in thrombi of certain mice) (Figure 4D). Depletion of neutrophils did not have much of an effect on the organizational structure and lining of the thrombi (Figure 4E), except that more type I and II lesions were scored, which likely reflected the (nonsignificant) slightly increased number of affected mice vs the control group. Increased liver fibrin deposition compared with siNEG control mice was evident, but no significant differences between both siSerpinc1/siProc treated groups were observed (67.8 ng/mg [9.3, 587.5] vs 51.9 ng/mg [10.9, 3126]; P = .931) (Figure 4F).

To investigate whether the thrombotic coagulopathy following siSerpinc1/siProc treatment coincided with altered formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), plasma levels of extracellular nucleosomes were used as a marker associated with NET formation.24-26 Nucleosome levels were increased in mice with VT compared with untreated mice (P = .003 and P < .001, respectively, siSerpinc1/siProc –αLy6G and siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G vs untreated controls) (supplemental Figure 10). However, no differences were found in plasma from mice with or without detectable neutrophils in the circulation (siSerpinc1/siProc –αLy6G: 46 U/mL [7, 756]; siSerpinc1/siProc +αLy6G: 59 U/mL [10, 771]; P = .448), suggesting that the (increased) extracellular nucleosomes in plasma of thrombotic animals were derived from damaged or dying cells other than neutrophils, showing the limitation of the use of nucleosomes as markers for NET formation.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of TF, FXII, platelets, and neutrophils in the pathophysiology of VT by using a mouse model that does not require additional manipulations other than silencing 2 liver-derived natural anticoagulants. In this model, TF and platelets were found to be rate-limiting factors for thrombus formation but not FXII and neutrophils, even though they were found to be associated with VT in other more invasive mouse models. This study therefore shows that distinct procoagulant pathways operate in mouse VT, dependent on the triggering stimulus.

Upon inhibition of thrombin7 or platelets (current study), a complete rescue of mice from VT was observed. In contrast, although antibody-mediated TF inhibition significantly delayed VT onset, a limited number of 1H1-treated mice developed VT. Possibly, 1H1 does not allow (prolonged) inhibition of all exposed TF. We speculate that incomplete inhibition also underlies the lack of impact of strong FVII inhibition by siF7 (∼95%). Because F3- or F7-deficient mice are not viable, preclinical studies in a setting of full absence of TF or FVII are precluded. For TF, mice have been generated that express human TF (∼1% of normal mouse TF27 ). Possibly these mice, or mice that conditionally (cell specifically) lack TF, may provide further insight into the role and source of TF that contribute to VT (ie, TF from cells of the hemostatic envelope, leukocytes, or microvesicles).

Although inhibition of the TF/extrinsic pathway of coagulation significantly affected VT after siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, deficiency for FXII (a key player for the intrinsic pathway of coagulation) did not. FXII is a therapeutic candidate for prevention of human VT because it may be involved in thrombus formation but not essential in hemostasis.28-30 Protection from experimental VT upon FXII deficiency or inhibition has been shown in multiple animal models.2,10,31-34 Despite these convincing preclinical data, thus far human data are missing to correlate FXII activity and thromboprotection. The present study shows that FXII is not rate-limiting for macroscopic VT. Interestingly, liver fibrin deposition was significantly lower in the F12−/− mice compared with their WT controls. Possibly, there are 2 separate mechanisms for liver fibrin formation and VT in the head upon siSerpinc1/siProc treatment, for which FXII plays a different role.

FXIIa activates FXI to its proteolytic active form FXIa.35 FXIa can activate coagulation factor IX to IXa, which initiates thrombin formation via the intrinsic pathway.20,36 In addition to FXII-mediated activation of FXI, in vitro studies show that FXI can be converted to FXIa by thrombin, via a positive feedback loop.37,38 However, in the presence of fibrinogen, thrombin does not activate FXI.39,40 As with FXII, FXI is currently tested as a therapeutic target to prevent human VT.36 In our study, F11−/− mice were not protected from VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C, indicating FXI is not rate-limiting in thrombus formation. However, the significant difference in weight loss that coincides with the thrombotic phenotype in F11−/− mice, and the differences in fibrin deposition in F12−/− mice hint toward a differential role for FXI and FXII in some aspects of VT. A role of FXII and FXI may become evident when VT is studied under milder conditions (ie, conditions with modest knockdown of antithrombin and protein C, or knockdown of antithrombin only, which coincides with a similar VT but at reduced incidence and delayed onset). Our results imply that VT upon inhibition of antithrombin and protein C is driven by the TF/extrinsic pathway of coagulation rather than the FXII/intrinsic pathway.

Platelets were identified as major players in experimental VT after IVC flow restriction. They are recruited early after flow restriction and are involved in stabilization and accumulation of innate immune cells.2 Thrombus formation is restrained in the absence of platelets. Also in the present study, platelets were essential for VT, which provides further evidence for an important role of platelets during experimental VT. We suggest that in mouse VT after inhibition of antithrombin and protein C, platelets are particularly important for the burst of fibrin and subsequent thrombus formation but not for the initial fibrin formation. This hypothesis is supported by the following: (1) thrombi were not detected in platelet-depleted mice, whereas liver fibrin deposition was increased compared with baseline levels (Figure 3F); (2) late platelet depletion just before the expected onset of the thrombotic phenotype fully rescued these respective mice; and (3) VWF, a protein important for platelet adherence but not for massive fibrin formation, is not involved in siSerpinc1/siProc–induced VT (whereas VWF is important in experimental VT after vena cava stenosis11,41,42 ).

The mechanism of how platelets contribute to VT after inhibition of antithrombin and protein C is presently unknown. The thrombi found in the large veins of the head frequently show banding and layered patterns, indicative of the so-called Lines of Zahn (Figures 3C and 4C-D; supplemental Figures 4 and 6A). Within the Lines of Zahn, platelets may possibly bind to fibrin via glycoprotein VI and integrins and become activated.43,44 Subsequently, platelets may expose negatively charged phospholipids, thereby catalyzing protease-mediated coagulation.45 Future studies using specific platelet receptor inhibitors and studies that dig deeper into the dose-dependent role of platelets (supplemental Figure 6B) may provide mechanistic insight into the role of platelets in VT.

Overall, the present study confirms a different but equally important role for platelets in our model compared with IVC models of VT, and it encourages further investigation of antiplatelet therapy inhibition for the prevention of (recurrent) human VT. Thus far, the use of antiplatelet agent aspirin was effective in preventing (recurrent) VT,46-48 albeit inferior to direct inhibition of coagulation proteases.49

Neutrophils have been linked to a role in experimental VT via a specialized cell death program in which NETs are released.24,50 In a VT mouse model based on IVC flow restriction, NETs released upon neutrophil recruitment to the (proinflammatory) vessel wall were indispensable for thrombus formation.2 In addition, in a VT model in which the IVC is activated by an electric current causing endothelial damage, neutrophils were shown to be the most common cell type present.51 Moreover, neutrophils and NETs have been identified in human specimens of VT.52-54

When VT follows silencing of natural anticoagulants, Ly6G-positive neutrophils were abundantly present within the thrombi, seemingly recruited and aligned to the fibrin layers. This finding is consistent with previous observations.1,2 However, in our mouse model, neutrophils were not rate-limiting in thrombus formation, which is in strong contrast to previous observations. Hence, the proposed role of neutrophils in VT pathophysiology seems not to hold true when impaired natural anticoagulation is the driving force and endothelial activation and/or vessel wall inflammation are considered absent (ie, not triggered by surgical handlings). Therefore, we speculate that neutrophils may have a limited role in human VT when clearly associated with impaired anticoagulation (eg, protein C/S or antithrombin deficiency). However, it is important to remember that we are modeling human disease and, as with all mouse VT models, the present model has limitations (eg, the location of the VT in the head).

In conclusion, we found that distinct procoagulant pathways operate in mouse VT, dependent on the triggering stimulus. When VT is induced by IVC flow restriction, TF, FXII, platelets, and neutrophils play a crucial role. In contrast, our data imply that FXII and neutrophils are not essential for VT when impaired natural anticoagulation is the driving force.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sander van Tilburg, Sophie Gerhardt (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands), and René van Oerle (Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands) for technical assistance. The authors thank Charles Esmon (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK) for providing the 59D8 antibody, David Gailani (Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN) for providing F11−/− mice, and Chantal Kroone (Leiden University Medical Center) for providing the TF-positive smooth muscle cells. The authors also thank Nigel Mackman (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC) for helpful discussions. T.R. acknowledges support from the German Research Society (SFB877, TP A11 and SFB841, TP B8), and a European Research Council grant (ERC-StG-2012-311575_F-12).

Authorship

Contribution: M.H., P.H.R., and B.J.M.v.V. designed the experiments; M.H., S.S.-A., T.S., E.H.L., D.S., B.M.L., S.S.Z., H.M.H.S., S.J.K., G.T.M.W., H.H.V., P.H.R., and B.J.M.v.V. performed experiments and analyzed data; T.R. and D.K. provided mice and/or materials; M.H. and B.J.M.v.V. wrote the paper; and all authors commented on manuscript drafts.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bart J. M. van Vlijmen, Einthoven Laboratory for Vascular and Regenerative Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Thrombosis and Hemostasis, Leiden University Medical Center, Albinusdreef 2, P.O. Box 9600, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: b.j.m.van_vlijmen@lumc.nl.

![Figure 2. FXII is not crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation peak heights. Thrombin generation was induced by 20 μg/mL ellagic acid (EA; left graph) or 1 pM TF (right graph) in plasma from WT mice (open circles) or F12-deficient mice (F12−/−; filled circles). Significance was determined by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Clinical phenotype in WT and F12−/− mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test. (C) Representative coronal head section stained by using the Carstairs’ method of a normal WT mouse (no siRNA treatment). (D-E) Representative coronal head sections of WT and F12−/− mice stained by using the Carstairs’ method. Both mice developed siSerpinc1/siProc–associated thrombotic coagulopathy. Black bars represent 2000 µm. (F) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: WT (n = 21); red bars: F12−/− (n = 22). (G) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in the control group (WT; open circles) and the F12−/− group (F12−/−; filled circles). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in a pool of uninjected WT, F12−/−, and F11−/− C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 5.9 ng/mg [3.8, 10.2], n = 8).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f2.png?Expires=1769534269&Signature=g2VgicrKlaw24gdBn34dJg9dfoqA~D6TIWlClGAqEjqFoN~kC4AlNRN3PrJS0Ltrfyag56TsOwwhroFeowtkSiRPJqv2WQeWP03Kup9yTTksJeLnEcFU3k-cBCDRoJZWaYBR~CVFaKsBbNsRgei2avEew2NLgnJMScuvJC5O-TpkixhOV7GXz3eXmc0wlaW69zPet~bdoH3k6qtBRZxFodCmHyMye0esnxyhTOX-Su7ZMPdr8T6PbAO~Dmm~hJ6ITPh~Dmk0bn2l7JKTwbz83Gk8TrneLy7GuLOZ~8Tr3jZ1XoHQWAEvizPjO4gujvU0MmohTonmhYhn0s~nBk6EAg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Platelets are crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood platelet numbers in mice not receiving siRNAs 3 days after injection with saline (–αGP1b; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse GP1b (+αGP1b; filled circles). P = .036, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical coagulopathy (blue bar) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice from the –αGP1b group died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Representative thrombus in a vein in the mandibular area in the control group (–αGP1b, panel C) and a representative vein in the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b, panel D) in the hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. thr, thrombus, with typical fibrin layers; rbc, postmortem clotted blood, rich in red blood cells; mus, striated muscle tissue. White bars represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 7 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombus categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αGP1b (n = 10); red bar: +αGP1b (n = 16). n.d., not detected. (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b) and the control group (–αGP1b). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines represent fibrin levels found in siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f3.png?Expires=1769534269&Signature=mhFna~WhWNst1bFnwP5KbwhA2vNQLWoglBFDmPNWG6aUWsE-tx8lVRVDf0bC9L0nsES0WDAVXU2TWbfIgE4UrVbjFayllu5dJHDijCMkM7NfjWovKMaP~Vh1QxvZKIjt-LO4p8xCbiEOiIZoPLgqzdtqrrY-V9B14Eulx6bxK6BH~~UCXh-CjTl6gp5aW9aUe4jnPjqgwygFzgh5CvM37mWrRPQGtFv23msvHk5yA-j2DleK1JxfhC9Y5JnvzmSe-TVQwBg9gy7XjDKk0jp2qJUbLFshifAFfNu3PEIOU7wYBQnTWLTw2zwunHkDFHxOJE7wkEnTpAJ6BpS80C1Ylw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Circulating neutrophils are not a major mediator of VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood neutrophils levels in mice 3 days after injection with a rat IgG control (–αLy6G; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse Ly6G (+αLy6G; filled circles). P < .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice in both groups (–αLy6G and +αLy6G) died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .317, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Ly6G staining of thrombi found in sections of the head. Ly6G staining visualizes neutrophils, which are seen as brown-colored cells in the figures. Representative sections are shown for the –αLy6G (panel C) and +αLy6G groups (panel D). Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Black lines represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 9 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αLy6G (n = 22); red bars: +αLy6G (n = 20). (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the control group (–αLy6G) and the neutrophil-depleted group (+αLy6G). P = .931, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in solely siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f4.png?Expires=1769534269&Signature=NuZpYmtOMStAycSNGJHcL4eZMX-6a6rFiqoNCbrH-k1MrOhJ3TvSz7Sqh7YfH2nUymH0bLIcUqvz2lK9d1Ywed5MYXDvlSVEQs1oUArqBD~jp07b~o6vrpb39Lv0orNrlrTHhbtvRAifKjxbLiRO1FdthvSWBVTbeSZSshFs4WZRHuFxqK7Q4V251UYm2-18Gsmjz4n0NF-irMmncBpC10vHMzETqgCUpMy5QFozcg61Q4CaQBJuYv-GMbxVM~ucAZ-2nIL2aAcgIjbc3YRkxMd0TcAz8-rqbRl4FXbJM5egOT2JPxSqZjMyEZTzPgqBQ0JoE2tAEFGoETmykBSk7Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 2. FXII is not crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Thrombin generation peak heights. Thrombin generation was induced by 20 μg/mL ellagic acid (EA; left graph) or 1 pM TF (right graph) in plasma from WT mice (open circles) or F12-deficient mice (F12−/−; filled circles). Significance was determined by using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Clinical phenotype in WT and F12−/− mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 2 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). P = 1.00, Fisher’s exact test. (C) Representative coronal head section stained by using the Carstairs’ method of a normal WT mouse (no siRNA treatment). (D-E) Representative coronal head sections of WT and F12−/− mice stained by using the Carstairs’ method. Both mice developed siSerpinc1/siProc–associated thrombotic coagulopathy. Black bars represent 2000 µm. (F) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: WT (n = 21); red bars: F12−/− (n = 22). (G) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver in the control group (WT; open circles) and the F12−/− group (F12−/−; filled circles). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in a pool of uninjected WT, F12−/−, and F11−/− C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 5.9 ng/mg [3.8, 10.2], n = 8).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f2.png?Expires=1770842121&Signature=JeDJ-gnsKPGZDtBbEfyTlIcMdd87T5bcJUp8LoTC1HDkhUqfjm8BDZRkPcJhr2sGA4mixkhrYaJOKpe4SM47tjuxZSN1m4-635w7MTlKp2ve0YUscopD3IlGdEppsR-3XwSR~Vz0b1mimhNNDsCV-wBawFlVUsPc~j99zXGXyvJe~3uLXGbElraxykaTTgNtIfF4czIhFuOG52hjmTo8cU0U3Ikq7fmL20xyV1YxBfdmHLMe3FJVhv3IrnYJ-KPC-8MXxPpq8DOn70e2Ag3CuPeqqCzyhhBs-8koj5Ug4fGZrHGrRdAIgdmDXqVZfy0fZfPaVUerhbEtLP9ig-n3Eg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 3. Platelets are crucial for VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood platelet numbers in mice not receiving siRNAs 3 days after injection with saline (–αGP1b; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse GP1b (+αGP1b; filled circles). P = .036, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice showing characteristic clinical coagulopathy (blue bar) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice from the –αGP1b group died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .001, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Representative thrombus in a vein in the mandibular area in the control group (–αGP1b, panel C) and a representative vein in the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b, panel D) in the hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections. thr, thrombus, with typical fibrin layers; rbc, postmortem clotted blood, rich in red blood cells; mus, striated muscle tissue. White bars represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 7 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombus categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αGP1b (n = 10); red bar: +αGP1b (n = 16). n.d., not detected. (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the platelet-depleted group (+αGP1b) and the control group (–αGP1b). P = .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines represent fibrin levels found in siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f3.png?Expires=1770842121&Signature=lmQdk6sOMG-ogGrrunJHctmhc22xp680zrkAiFCNrI1K~iGoUcm640nqPKhkedETFA5cQy1Xv6okrHIDn4t-83ePKolzYXpx1ilzSJKDmhijN4UoCljvV8dUhpem7K9fRkFtHSW0bd2nTiP7kAzP1r7RlceLCUFBx0un44KjpoLvvqF5Ax-VyThtHKXWf5S-AIdtsfX7a84KuKsQWmVfJjE8wGMjWT92NWdo96SClU6ChUdMMENttzE4nJ-Q-ES9EvEhZhoMTC~YVzsy9-j~TO8eYLuOvOx-NNO~xJUAmzEBl0txcZzsH1rUmxnt4mhGVVBLiSBBINjNQ-DGgdUBZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 4. Circulating neutrophils are not a major mediator of VT that follows inhibition of antithrombin and protein C. (A) Blood neutrophils levels in mice 3 days after injection with a rat IgG control (–αLy6G; open circles) or a rat monoclonal antibody targeting mouse Ly6G (+αLy6G; filled circles). P < .001, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Scoring of the clinical phenotype in mice treated with siRNAs targeting Serpinc1 and Proc. Mice exhibiting characteristic clinical signs (blue bars) and mice unaffected (red bars) 3 days after siRNA treatment (end of experiment). One of the mice in both groups (–αLy6G and +αLy6G) died as a result of the thrombotic coagulopathy. P = .317, Fisher’s exact test. (C-D) Ly6G staining of thrombi found in sections of the head. Ly6G staining visualizes neutrophils, which are seen as brown-colored cells in the figures. Representative sections are shown for the –αLy6G (panel C) and +αLy6G groups (panel D). Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining. Black lines represent 100 μm. Supplemental Figure 9 presents enlargement of the images from both panels. (E) Descriptive scoring for the type of detected thrombi. 0: no thrombi found; I + II: thrombi categories were based on structure and layering. Blue bars: –αLy6G (n = 22); red bars: +αLy6G (n = 20). (F) Levels of fibrin deposition in the liver of the control group (–αLy6G) and the neutrophil-depleted group (+αLy6G). P = .931, Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Solid and dashed lines indicate fibrin levels found in solely siNEG-injected C57BL/6J female mice (median and range, respectively, 4.5 ng/mg [3.1, 5.7]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/133/19/10.1182_blood-2018-06-853762/3/m_blood853762f4.png?Expires=1770842121&Signature=qkVfizQNOcTsCgnTCe4bOLUAtoNwfGF3fpRJTpytlKVccX6CUx97D2yU8nsdBnuNmYWdwrHN0vLAgYMPM326GoyTMimijPHa0qrLDa4UW3AyBkmO1jlP6gJGflihOnHUVq8T7~Knu59uLbjq1lllSJa-OwihyUvaxKeIzBFoJZUb0Bx02jL3WPdDdblmQyTTCcOFmC9s2kptN9ZJgPWmE894Thh0R8qf49X8~6vq2SdDXoB0mmf-ce~0R6kIBZ2y55nXljRki3wbCNsdbVRv01aH-vODVbPABo8pxeCczYboPfRxaAnoO2lnUwxVBFmDUo~1JI6sbmLJ5kzmL-QM9g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)