Key Points

CD30 signaling drives the expansion of B1 cells and PBs/PCs in transgenic mice.

Chronic CD30 signaling in murine B cells results in the development of B-cell lymphomas.

Abstract

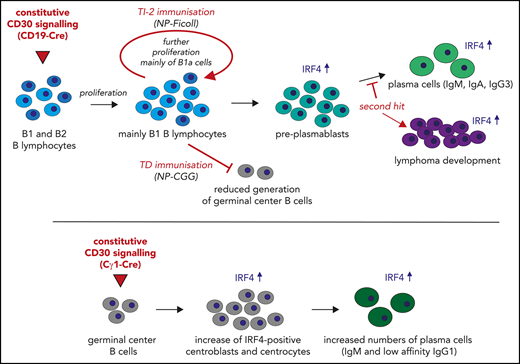

CD30 is expressed on a variety of B-cell lymphomas, such as Hodgkin lymphoma, primary effusion lymphoma, and a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma subgroup. In normal tissues, CD30 is expressed on some activated B and T lymphocytes. However, the physiological function of CD30 signaling and its contribution to the generation of CD30+ lymphomas are still poorly understood. To gain a better understanding of CD30 signaling in B cells, we studied the expression of CD30 in different murine B-cell populations. We show that B1 cells expressed higher levels of CD30 than B2 cells and that CD30 was upregulated in IRF4+ plasmablasts (PBs). Furthermore, we generated and analyzed mice expressing a constitutively active CD30 receptor in B lymphocytes. These mice displayed an increase in B1 cells in the peritoneal cavity (PerC) and secondary lymphoid organs as well as increased numbers of plasma cells (PCs). TI-2 immunization resulted in a further expansion of B1 cells and PCs. We provide evidence that the expanded B1 population in the spleen included a fraction of PBs. CD30 signals seemed to enhance PC differentiation by increasing activation of NF-κB and promoting higher levels of phosphorylated STAT3 and STAT6 and nuclear IRF4. In addition, chronic CD30 signaling led to B-cell lymphomagenesis in aged mice. These lymphomas were localized in the spleen and PerC and had a B1-like/plasmablastic phenotype. We conclude that our mouse model mirrors chronic B-cell activation with increased numbers of CD30+ lymphocytes and provides experimental proof that chronic CD30 signaling increases the risk of B-cell lymphomagenesis.

Introduction

CD30 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily.1 Initially, CD30 was defined as a marker of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL),2 but it was later also detected on anaplastic large-cell lymphoma,2 primary effusion lymphomas,3,4 and a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subgroup.5,6 In addition, CD30 is expressed on virally infected lymphocytes, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–infected B cells or HIV-infected T cells, as well as on lymphocytes of patients with autoimmune diseases.7 Elevated levels of soluble CD30, which arise from the extracellular cleavage of CD30, are often detectable in the sera of patients with CD30+ lymphomas and chronic infections.1,8 In healthy persons, CD30 is expressed only on a few activated B and T lymphocytes. CD30+ B lymphocytes are generally localized in the extrafollicular (EF) regions of lymphoid tissues.9-11 A few CD30+ B cells are located in germinal centers (GCs) and are considered to be a subgroup of positively selected centrocytes (CCs).12

The role of CD30 signaling in B lymphocytes is still poorly understood. Studies in CD30 knockout mice have not revealed a clear function of CD30 signaling in B cells.13 CD30 knockout mice had a defect in sustaining GC responses and inducing secondary immune responses; however, this defect was attributed to the impaired generation of CD4+ memory T cells.14 No studies have investigated whether CD30-deficient B cells also contribute to this phenotype. Similarly, although CD30 is highly expressed on several B-cell lymphomas, it is unclear whether deregulated CD30 signaling actively drives B-cell lymphomagenesis. Because CD30+ lymphomas are often correlated with viral infections,15 there might be a correlation between chronic immune stimulation and development of CD30+ lymphomas. This hypothesis was strengthened by recent cohort studies showing that elevated levels of soluble CD30 in immunocompetent healthy persons were associated with an increased risk of developing non-HL.16-20

To study the role of CD30 signaling in B-cell activation and lymphomagenesis, we generated a new transgenic mouse strain (LMP1/CD30flSTOP mice) expressing a constitutive active CD30 receptor upon Cre-mediated recombination. We demonstrate that B cell–specific expression of LMP1/CD30 led to the expansion of B1 cells and enhanced plasma cell (PC) differentiation. Furthermore, we provide evidence that chronic CD30 signaling resulted in lymphoma development.

Methods

Mice

The LMP1/CD30 transgene was inserted together with a loxP-flanked stop cassette into the Rosa26 locus of embryonic stem cells. Chimeric mice were obtained from the microinjection of embryonic stem cells into blastocysts and used to establish the LMP1/CD30flSTOP transgenic mouse line. For the B cell–specific expression of LMP1/CD30, we used CD19-Cre mice or Cγ1-Cre mice,21,22 which were kindly provided by Klaus Rajewsky. R26/CAG-CARΔ1StopF mice were used as reporter mice.23 Mice were analyzed on a BALB/c background. Mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions, and experiments were performed in compliance with the German Animal Welfare Law and were approved by the Institutional Committee on Animal Experimentation and the government of Upper Bavaria.

Cell purification

B cells were isolated from splenic-cell suspensions using CD43 MicroBeads or the Pan-B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi-Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (magnetic-activated cell sorting separation). B1 (CD23lowCD43+) and B2 cells (CD23+CD43−) were sorted with a BD FACSAria III.

Protein detection

Whole-cell extracts were prepared with NP40 lysis buffer. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were generated with the NE-PER Kit (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA). Western blot analyses were performed as described previously24 or with the WES system, a fully automated western blot system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (additional information in supplemental Methods).

In vitro cultures

In vitro culture conditions are described in supplemental Methods.

Flow cytometry

All fluorescence-activated cell sorting antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (Heidelberg, Germany), except for the coxsackie/adenovirus receptor (CAR) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX).

For intracellular fluorescence-activated cell sorting staining, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with methanol. Analysis was performed with the FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) or LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences). Results were analyzed with FlowJo software (version 10; TreeStar).

Histology

Immunohistochemistry was performed by using OCT (VWR Chemicals, Radnor, PA) or paraffin-embedded tissues. Further information is given in supplemental Methods.

Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and P values were calculated using Prism7 software (GraphPad Software) through Student unpaired t tests, 1- or 2-way analyses of variance, or Mann-Whitney U tests, where appropriate. Because of their lognormal distribution, values for some parameters like immunoglobulin titers and protein and messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were logtransformed before statistical analysis.

Results

Expression of CD30 on murine B cells

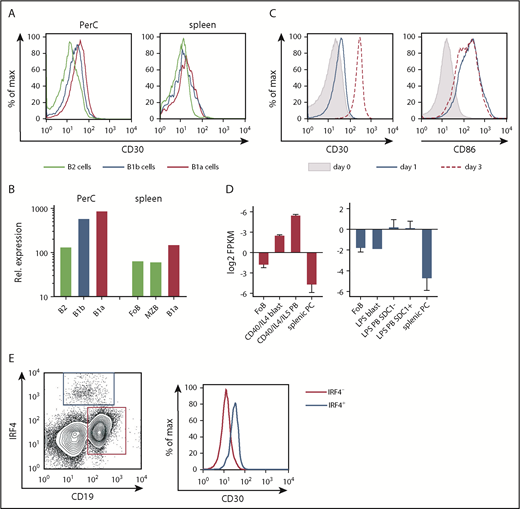

We examined CD30 surface expression on different mature B-cell populations ex vivo and after in vitro activation. In the peritoneal cavity (PerC), B1 cells expressed more CD30 than B2 cells, with slightly higher levels in B1a than B1b cells. These expression differences were also observed in splenic B cells but to a lower extent (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1A). This was in accordance with in silico data revealing CD30 mRNA expression was higher in B1a and B1b cells compared with B2 cells in the PerC and was slightly increased in B1a compared with follicular B cells and marginal zone B cells in the spleen (Figure 1B). Mitogenic stimulation of splenic B cells in vitro led to an upregulation of CD30, with CD30 being upregulated more strongly in B1 than in B2 cells (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 1B-C).

Expression of CD30 on B cells. (A) The histograms show an overlay of CD30 surface expression on B1a (CD5+B220lowCD19+), B1b (CD5lowB220lowCD19+), and B2 cells (B220highCD19+) of the PerC and spleen (n = 3). (B) In silico analysis of immgen.org data showing CD30 (TNFRSF8) mRNA expression in different B-cell populations of the PerC and spleen. (C) The overlays show CD30 and CD86 surface expression of splenic B cells in the absence of stimulation (day 0) and after 1 or 3 days of CD40 plus IgM stimulation. Staining of CD86 was used as positive control for B-cell activation (n = 3). (D) CD30 mRNA expression at different B-cell activation stages after CD40 and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of unstimulated follicular B (FoB) cells, CD40/IL4 blasts (B220+CD138−), CD40/IL4/IL5 plasmablasts (PBs) (B220lowCD138+), LPS blasts (BLIMP1−CD138−), LPS PB SDC− (Blimp1+CD138−), LPS PB SDC1+ (BLIMP1+CD138+), and splenic PCs. CD30 mRNA expression was determined by in silico analysis of expression data published by Shi et al.49 (E) The histogram shows an overlay of CD30 surface expression of IRF4+ vs IRF4− splenic B cells of a control mouse 3 days after immunization with NP-Ficoll. Gating was performed as shown in the dot plot. Dot plots were pregated on a large lymphocyte gate and Thy1.2− cells. The analysis is representative of 2 independent experiments with 3 mice each. FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped; MZB, marginal zone B cells.

Expression of CD30 on B cells. (A) The histograms show an overlay of CD30 surface expression on B1a (CD5+B220lowCD19+), B1b (CD5lowB220lowCD19+), and B2 cells (B220highCD19+) of the PerC and spleen (n = 3). (B) In silico analysis of immgen.org data showing CD30 (TNFRSF8) mRNA expression in different B-cell populations of the PerC and spleen. (C) The overlays show CD30 and CD86 surface expression of splenic B cells in the absence of stimulation (day 0) and after 1 or 3 days of CD40 plus IgM stimulation. Staining of CD86 was used as positive control for B-cell activation (n = 3). (D) CD30 mRNA expression at different B-cell activation stages after CD40 and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation of unstimulated follicular B (FoB) cells, CD40/IL4 blasts (B220+CD138−), CD40/IL4/IL5 plasmablasts (PBs) (B220lowCD138+), LPS blasts (BLIMP1−CD138−), LPS PB SDC− (Blimp1+CD138−), LPS PB SDC1+ (BLIMP1+CD138+), and splenic PCs. CD30 mRNA expression was determined by in silico analysis of expression data published by Shi et al.49 (E) The histogram shows an overlay of CD30 surface expression of IRF4+ vs IRF4− splenic B cells of a control mouse 3 days after immunization with NP-Ficoll. Gating was performed as shown in the dot plot. Dot plots were pregated on a large lymphocyte gate and Thy1.2− cells. The analysis is representative of 2 independent experiments with 3 mice each. FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped; MZB, marginal zone B cells.

Moreover, in silico analysis revealed upregulation of CD30 mRNA in blasts and PBs after in vitro stimulation (Figure 1D), in accordance with a higher CD30 surface expression on IRF4+ PBs/PCs compared with IRF4− B cells (Figure 1E). These data show that B1 cells and PBs express more CD30 on their cell surfaces than naïve B2 cells.

Generation of conditional transgenic mouse strain LMP1/CD30flSTOP

To study the function of CD30 in B-cell activation and lymphomagenesis, we generated mice conditionally expressing a constitutive active CD30 receptor. We cloned an LMP1/CD30 fusion gene consisting of the transmembrane domain of the EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1TM) and the intracellular signaling domain of CD30. LMP1/CD30 exerts ligand-independent CD30 signaling by self-aggregation of LMP1TM in the plasma membrane. We have already demonstrated the efficacy of this approach by generating a constitutive active CD40 receptor.24,25 The functionality of the LMP1/CD30 fusion protein was verified by an NF-κB–dependent luciferase activity assay in HEK293 cells after transient transfection with an LMP1/CD30 expression construct (supplemental Figure 2A). The transgene was inserted together with a loxP-flanked stop cassette into the rosa26 locus. After removal of the stop cassette by Cre, LMP1/CD30 was expressed under the control of the rosa26 promoter together with the reporter gene hCD2 (supplemental Figure 2B).

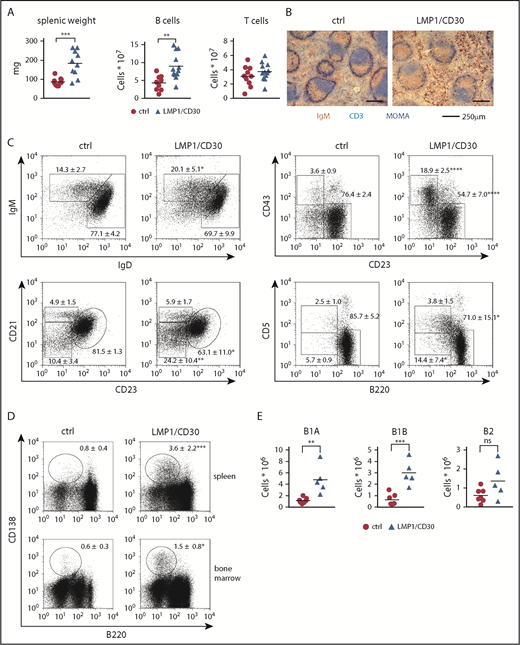

Constitutive CD30 expression in B cells leads to expansion of mature B cells

To activate LMP1/CD30 in all B cells, we crossed LMP1/CD30stopfl mice with CD19-Cre mice. In all analyses, we used mice that were heterozygous for LMP1/CD30 and CD19-Cre, designated LMP1/CD30 hereafter. Controls were mostly CD19-Cre+/− mice. Deletion efficiency of the stop cassette was low in developing B cells of the bone marrow but reached >94% in mature B cells (supplemental Figure 3A-B). LMP1/CD30 protein from splenic B lymphocytes was detected at a size of ∼54 kDa (supplemental Figure 3C).

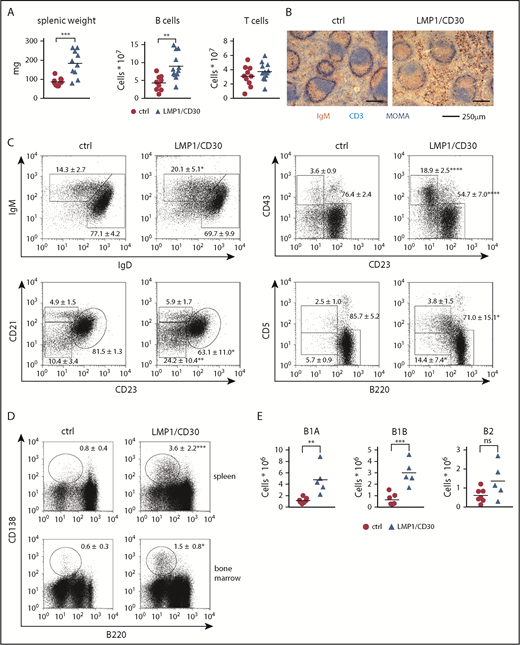

LMP1/CD30 mice displayed splenomegaly and significantly increased B-cell numbers in the spleen compared with controls, whereas T-cell numbers were comparable (Figure 2A). Splenic sections revealed a normal follicle structure with a B- and T-cell zone surrounded by a marginal zone. However, more B cells expressing high levels of IgM were located in the red pulp compared with control sections (Figure 2B). Analysis of the B-cell compartment in the spleen revealed an expansion of mature B cells, with B1 cells and PBs/PCs being the most highly expanded (Figure 2C-D; supplemental Table 2). In all B-cell subpopulations, expression of endogenous CD30 on the cell surface was comparable between mutant and control mice (supplemental Figure 3D). Increased percentages of PBs/PCs and B1 cells were also detected in other organs. Thus, percentages of PCs were elevated in the bone marrow (Figure 2D), and percentages of B1 cells were elevated in lymph nodes and blood (supplemental Figure 4A-B). In the PerC, total lymphocyte numbers were increased (supplemental Figure 4C), with a four- to fivefold increase in B1a- and B1b-cell numbers (Figure 2E). Consequently, constitutive CD30 signaling resulted in the expansion of mature B lymphocytes, with a stronger expansion of B1 cells and PBs/PCs.

Constitutive CD30 expression in B cells leads to the expansion of B1 cells and PCs. (A) Splenic weights and absolute splenic B- and T-cell numbers from LMP1/CD30 mice and controls (ctrl) age 8 to 12 weeks are shown. (B) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30 and ctrl mice were stained for immunoglobulin M (IgM; brown/red), CD3 (light blue), and MOMA-1 (dark blue) to visualize B cells, T cells, and metallophilic macrophages, respectively. Slides were analyzed with an Axioskop (Zeiss) with a Zeiss Plan NEOFLUAR (objective 10×/0.3). Images were obtained with an AxioCam MRc5 digital camera in combination with AxioVision rel.4.6.3.0 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany). (C) Splenic B lymphocytes (CD19+) were analyzed for the expression of IgM/IgD, distribution of follicular B cells (CD21intCD23+) and marginal zone B cells (CD21highCD23low), distribution of B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 (CD43−CD23+) cells, and distribution of B1a (CD5+B220low), B1b (CD5lowB220low), and B2 (B220+CD5low) by flow cytometry (n ≥ 6). (D) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic and bone marrow lymphocytes stained for PCs (B220−/lowCD138+). Cells were pregated using a large lymphocyte gate (n ≥ 6). Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots indicate the mean and standard deviation values of the percentages of the gated populations. (E) Total numbers of B lymphocytes (CD19+) in the PerC were counted and calculated based on their staining: B1a (CD5+B220low), B1b (CD5lowB220low) and B2 (CD5lowB220+). B cells from LMP1/CD30 mice were gated on hCD2. Data were collected from 8- to 16-week-old mice. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

Constitutive CD30 expression in B cells leads to the expansion of B1 cells and PCs. (A) Splenic weights and absolute splenic B- and T-cell numbers from LMP1/CD30 mice and controls (ctrl) age 8 to 12 weeks are shown. (B) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30 and ctrl mice were stained for immunoglobulin M (IgM; brown/red), CD3 (light blue), and MOMA-1 (dark blue) to visualize B cells, T cells, and metallophilic macrophages, respectively. Slides were analyzed with an Axioskop (Zeiss) with a Zeiss Plan NEOFLUAR (objective 10×/0.3). Images were obtained with an AxioCam MRc5 digital camera in combination with AxioVision rel.4.6.3.0 software (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Jena, Germany). (C) Splenic B lymphocytes (CD19+) were analyzed for the expression of IgM/IgD, distribution of follicular B cells (CD21intCD23+) and marginal zone B cells (CD21highCD23low), distribution of B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 (CD43−CD23+) cells, and distribution of B1a (CD5+B220low), B1b (CD5lowB220low), and B2 (B220+CD5low) by flow cytometry (n ≥ 6). (D) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic and bone marrow lymphocytes stained for PCs (B220−/lowCD138+). Cells were pregated using a large lymphocyte gate (n ≥ 6). Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots indicate the mean and standard deviation values of the percentages of the gated populations. (E) Total numbers of B lymphocytes (CD19+) in the PerC were counted and calculated based on their staining: B1a (CD5+B220low), B1b (CD5lowB220low) and B2 (CD5lowB220+). B cells from LMP1/CD30 mice were gated on hCD2. Data were collected from 8- to 16-week-old mice. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

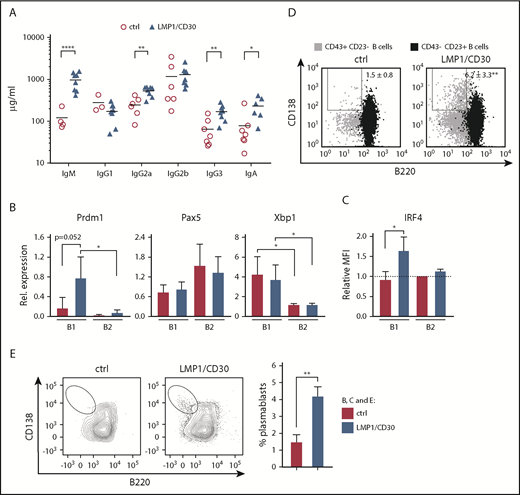

Constitutive CD30 signaling enhances PC differentiation

The upregulation of CD30 in PBs (Figure 1D-E) and the expansion of PBs/PCs in LMP1/CD30 mice suggest a role for CD30 signaling in PC differentiation. In accordance with this, total IgM, IgG2a, IgG3, and IgA antibody titers in the serum were elevated (Figure 3A). Moreover, unstimulated and stimulated LMP1/CD30+ B cells generated more PBs and secreted more IgM than controls in in vitro cultures (supplemental Figure 5A-C). Analysis of the expression levels of Blimp1 (Prdm1), Irf4, and Xbp1, which are upregulated, and Pax5, which is downregulated during PC differentiation,26 revealed that splenic B1 cells of LMP1/CD30 mice expressed more Prdm1 mRNA and higher IRF4 protein levels compared with controls (Figure 3B-C). Furthermore, the percentage of CD138+B220low cells within the B1-cell fraction was higher in LMP1/CD30 mice than in controls (Figure 3D), suggesting that LMP1/CD30 expression drives PC differentiation of B1 cells. This was corroborated by our finding that sorted LMP1/CD30-expressing B1 cells differentiated to PBs in vitro, even in the absence of additional stimulation (Figure 3E).

Constitutive CD30 expression expands PCs in vivo and in vitro. (A) Serum concentrations of total immunoglobulins of the indicated isotypes were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Horizontal bars represent mean values. (B) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis showing the relative expression of Prdm1 (BLIMP1), Xbp1, and Pax5 in CD43+CD23low B1 vs CD43−CD23+ B2 cells from control (ctrl) and LMP1/CD30 mice. Expression was standardized to the housekeeping gene Ywhaz. (C) Relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IRF4 in B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 cells (CD43−CD23+) from LMP1/CD30 and ctrl mice. Relative MFIs were related to the MFI of ctrl B2 cells, which was set as 1. Data are from 3 independent experiments. (D) B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 cells (CD43−CD23+) were analyzed for their CD138/B220 expression and shown as an overlay (n ≥ 4). (E) B1 cells (CD43+CD23low) were sorted and reanalyzed as described in supplemental Figure 6. CD138+B220low cells were excluded in the sorted population. After sorting, B1 cells (CD138−CD43+CD23low) were cultivated without stimulation for 3 days and subsequently analyzed for their CD138/B220 expression. The dot plots show the gating strategy, and the graph compiles data of percentages of CD138highB220low cells from the indicated genotypes from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

Constitutive CD30 expression expands PCs in vivo and in vitro. (A) Serum concentrations of total immunoglobulins of the indicated isotypes were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Horizontal bars represent mean values. (B) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction analysis showing the relative expression of Prdm1 (BLIMP1), Xbp1, and Pax5 in CD43+CD23low B1 vs CD43−CD23+ B2 cells from control (ctrl) and LMP1/CD30 mice. Expression was standardized to the housekeeping gene Ywhaz. (C) Relative mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IRF4 in B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 cells (CD43−CD23+) from LMP1/CD30 and ctrl mice. Relative MFIs were related to the MFI of ctrl B2 cells, which was set as 1. Data are from 3 independent experiments. (D) B1 (CD43+CD23low) and B2 cells (CD43−CD23+) were analyzed for their CD138/B220 expression and shown as an overlay (n ≥ 4). (E) B1 cells (CD43+CD23low) were sorted and reanalyzed as described in supplemental Figure 6. CD138+B220low cells were excluded in the sorted population. After sorting, B1 cells (CD138−CD43+CD23low) were cultivated without stimulation for 3 days and subsequently analyzed for their CD138/B220 expression. The dot plots show the gating strategy, and the graph compiles data of percentages of CD138highB220low cells from the indicated genotypes from 3 independent experiments. *P < .05, **P < .01, ****P < .0001. ns, not significant.

In contrast, LMP1/CD30-expressing B2 cells did not spontaneously differentiate to PBs in vitro (supplemental Figure 7A-B). However, PC differentiation was enhanced upon CD40 stimulation in comparison with controls (Figure 4A). Interestingly, CD40 stimulation of B2 cells generated CD23lowCD43+ cells, and the percentage of this population was higher in LMP1/CD30-expressing cells compared with control B cells (Figure 4B). In both genotypes, the CD23lowCD43+ population contained a fraction of CD138+ cells (Figure 4C) and expressed higher levels of CXCR4 and lower levels of CD22 (Figure 4D), in accordance with a plasmablastic phenotype.27 Therefore, we assume that the expanded CD23lowCD43+ population in LMP1/CD30 mice consisted of a mixture of expanded B1 cells and PC progenitors, which have a similar gene expression profile (supplemental Figure 8). PBs could originate spontaneously either from B1 cells or from CD40-stimulated B2 cells.

Increased PC differentiation of B2 cells upon CD40 stimulation. (A-B) Sorted splenic B2 cells (CD23+CD43−) from LMP1/CD30 and control (ctrl) mice were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody for 3 days and analyzed for their B220/CD138 and CD43/CD23 surface expression. Sorting strategy and purity of the sorted B2 cells are shown in supplemental Figure 7A. Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots indicate mean and standard deviation values of the percentages of gated populations in different FACS analyses. (C) CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells were gated as shown in panel B. B220/CD138 staining of CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells is shown as an overlay (n ≥ 3). (D) Histograms show overlays of CXCR4 and CD22 surface expression of CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells from ctrl and LMP1/CD30 mice. (E) Determination of phosphorylated STAT6 (pSTAT6) and pSTAT3 levels in nuclear extracts of splenic B cells stimulated with an anti-CD40 antibody for the indicated time points. Splenic B cells were purified by MACS using magnetic beads binding to CD43 to remove most of the B1 cells. Protein levels were analyzed and quantified using the WES separation system and software. Determination of p65 (F) and IRF4 (G) in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from the indicated genotypes. B cells purified by CD43 depletion were stimulated for 10 minutes with anti-CD40 antibody. Protein levels of p65 and IRF4 were analyzed and quantified using the WES separation system and software. For each mouse, the value after stimulation was standardized with the corresponding unstimulated value (n ≥ 5). (H) pJAK3 levels were analyzed in the cytoplasm of unstimulated splenic B lymphocytes. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001.

Increased PC differentiation of B2 cells upon CD40 stimulation. (A-B) Sorted splenic B2 cells (CD23+CD43−) from LMP1/CD30 and control (ctrl) mice were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody for 3 days and analyzed for their B220/CD138 and CD43/CD23 surface expression. Sorting strategy and purity of the sorted B2 cells are shown in supplemental Figure 7A. Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots indicate mean and standard deviation values of the percentages of gated populations in different FACS analyses. (C) CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells were gated as shown in panel B. B220/CD138 staining of CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells is shown as an overlay (n ≥ 3). (D) Histograms show overlays of CXCR4 and CD22 surface expression of CD23lowCD43+ and CD23+CD43− cells from ctrl and LMP1/CD30 mice. (E) Determination of phosphorylated STAT6 (pSTAT6) and pSTAT3 levels in nuclear extracts of splenic B cells stimulated with an anti-CD40 antibody for the indicated time points. Splenic B cells were purified by MACS using magnetic beads binding to CD43 to remove most of the B1 cells. Protein levels were analyzed and quantified using the WES separation system and software. Determination of p65 (F) and IRF4 (G) in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from the indicated genotypes. B cells purified by CD43 depletion were stimulated for 10 minutes with anti-CD40 antibody. Protein levels of p65 and IRF4 were analyzed and quantified using the WES separation system and software. For each mouse, the value after stimulation was standardized with the corresponding unstimulated value (n ≥ 5). (H) pJAK3 levels were analyzed in the cytoplasm of unstimulated splenic B lymphocytes. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001.

Next, we analyzed which signaling pathways were responsible for this phenotype. We detected higher phosphorylated STAT3 (pSTAT3) and pSTAT6 as well as p65 and IRF4 levels in the nuclear fractions of CD40-stimulated LMP1/CD30-expressing splenic B2 cells compared with controls (Figure 4E-G). CD40 has been shown to interact with JAK3, leading to STAT3 and STAT6 phosphorylation.28,29 Therefore, we studied whether LMP1/CD30 activates JAK3. Indeed, basal JAK3 phosphorylation was increased in LMP1/CD30+ B cells in comparison with controls (Figure 4H). These data suggest that the higher basal activation of JAK3 in LMP1/CD30 B cells enhanced activation of JAK/STAT signaling by CD40. Interestingly, phosphorylation of STAT3 has a crucial role in PC differentiation by upregulating BLIMP1,30,31 and IRF4 is a known NF-κB target gene.32,33 Therefore, we conclude that CD30 signaling in cooperation with CD40 signaling strengthens the upregulation of IRF4 and BLIMP1 by enhancing JAK/STAT and NF-κB signaling and thus leads to enhanced PC differentiation.

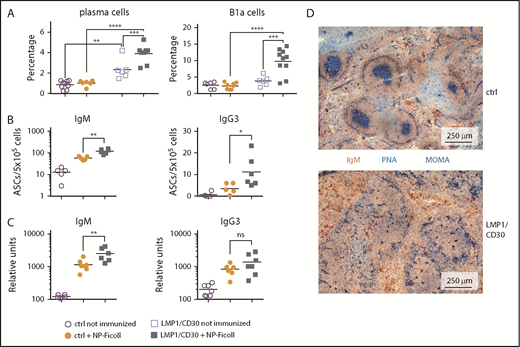

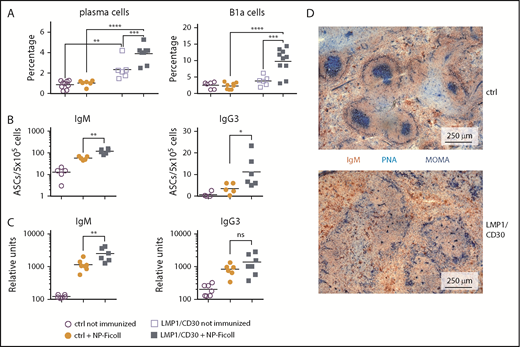

LMP1/CD30 enhances generation of splenic B1a cells and PCs upon TI-2 immunization

Next, we analyzed whether the enhanced PC differentiation resulted in elevated immune responses. Immunization with the TI-2 antigen NP Ficoll resulted in a further increase in the percentages of total PCs and B1a cells in LMP1/CD30 mice but not in controls (Figure 5A). Moreover, immunized LMP1/CD30 mice had more NP-specific IgM and IgG3 PCs in the spleen and displayed higher NP/IgM titers in the serum than controls (Figure 5B-C). These data show that CD30 signaling drove PC differentiation and expansion of B1a cells upon TI-2 immunization.

CD30 signaling enhances expansion of B1a cells and PCs upon TI-2 immunization. (A) Mice were immunized with NP-Ficoll and analyzed 14 days postimmunization. Percentages of PCs (CD138+B220lowGr1−Thy1.2.−CD11b−) and B1a cells (CD5+CD19+B220low) in the spleen were determined by flow cytometry. Fourteen days after immunization, IgM- and IgG3-secreting PCs from the spleen were determined by ELISpot analysis (B) and serum titers of IgM and IgG3 antibodies binding to NP17-BSA were determined by ELISA (C). (D) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30 and control (ctrl) mice were stained for GC B cells (PNA; blue), Metallic macrophages surrounding the primary follicles (MOMA; blue) and B cells (IgM; red/brown) 14 days after NP-CGG immunization. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001. ASC, antibody secreting cell.

CD30 signaling enhances expansion of B1a cells and PCs upon TI-2 immunization. (A) Mice were immunized with NP-Ficoll and analyzed 14 days postimmunization. Percentages of PCs (CD138+B220lowGr1−Thy1.2.−CD11b−) and B1a cells (CD5+CD19+B220low) in the spleen were determined by flow cytometry. Fourteen days after immunization, IgM- and IgG3-secreting PCs from the spleen were determined by ELISpot analysis (B) and serum titers of IgM and IgG3 antibodies binding to NP17-BSA were determined by ELISA (C). (D) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30 and control (ctrl) mice were stained for GC B cells (PNA; blue), Metallic macrophages surrounding the primary follicles (MOMA; blue) and B cells (IgM; red/brown) 14 days after NP-CGG immunization. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001. ASC, antibody secreting cell.

To analyze whether CD30 signaling had the same effect during thymus-dependent immune responses, we immunized mice with the thymus-dependent antigen NP-CGG. Strikingly, GC formation was strongly impaired in LMP1/CD30 mice, suggesting that LMP1/CD30 expression in pre-GC B cells interfered with the initiation of GCs (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 9A). To analyze whether this was due to the antigen that we used for immunization, we analyzed GCs in Peyer’s patches (PPs), where they are continuously generated independently of immunization (supplemental Figure 9B). GC B cells were detected in PPs of LMP1/CD30 mice; however, the percentages of hCD2+ B cells were lower in GC in comparison with non-GC B cells, suggesting a counter selection of LMP1/CD30-expressing GC B cells in PPs as well (supplemental Figure 9C). Because a large fraction of mucosal IgA+ PCs are generated in PPs,34,35 we asked whether the impaired intestinal germinal center reaction in LMP1/CD30 mice led to a reduction of IgA+ PCs in PPs and the lamina propria. Percentages of IgA+ PCs in LMP1/CD30 mice and controls were similar in both the lamina propria and PPs (supplemental Figure 9D). However, in LMP1/CD30 mice, most of the IgA+ PCs did not express hCD2, suggesting that they were generated mainly from undeleted GC cells (supplemental Figure 9C). These findings suggest that the elevated IgA titers in LMP1/CD30 mice were due to the increased number of B1 cells, which show efficient class switching to IgA upon TI stimulation.36 Therefore, constitutive CD30 signaling in mature B cells resulted in enhanced TI immune responses but strongly interfered with the GC reaction.

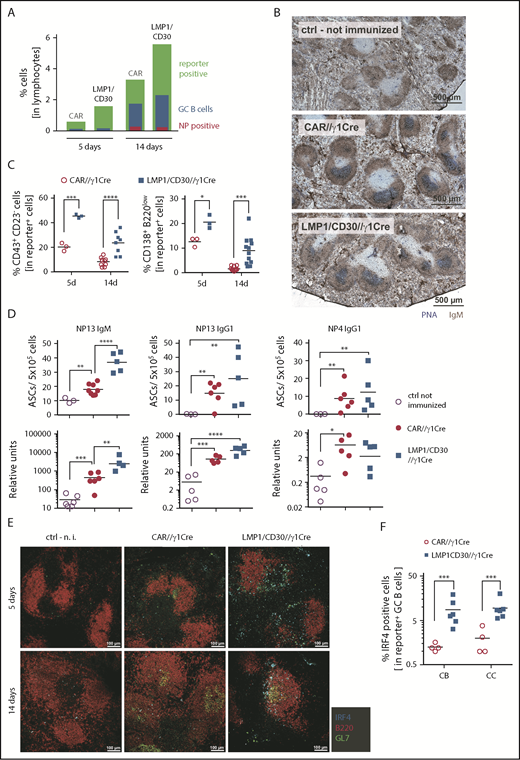

LMP1/CD30 expression drives PC differentiation in GC and non-GC B cells

To restrict LMP1/CD30 expression to GC (and post-GC) B cells, thereby preventing the blockade of GC establishment by constitutive CD30 signaling, we crossed LMP1/CD30flSTOP mice with Cγ1-Cre mice22 (hereafter named LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre). For controls, we used the reporter mice R26/CAG-CARΔ1StopF, expressing a truncated version of the human CAR upon Cre-mediated recombination.23 Immunization with NP-CGG resulted in significant more reporter-positive B cells in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice than in controls (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 10A). Because the percentage of GC B cells within the reporter-positive cells was lower in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice (supplemental Figure 10B), the increased number of reporter-positive cells could be mainly attributed to non-GC B cells (Figure 6A). Total percentages of reporter-positive GC and NP+ GC B cells within all lymphocytes were comparable in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre and CAR//γ1-Cre mice (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 10B-C). In addition, GCs were clearly visible in splenic sections of LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice 14 days postimmunization (Figure 6B). These data indicate that GC B cells were generated if LMP1/CD30 expression started in GC B cells.

CD30 signaling enhances PC differentiation upon TD immunization with NP-CGG. (A) Displayed are the percentages of reporter-positive lymphocytes, CD38lowCD95high reporter-positive GC B cells, and NP+ reporter-positive GC B cells in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice and CAR//γ1-Cre upon NP-CGG immunization at the indicated time points. Gating strategy of reporter-positive lymphocytes, GC B cells, and NP+ GC B cells, as well as graphs compiling values of different experiments including the statistics, is shown in supplemental Figure 10A-C. (B) GCs were clearly visible 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre and CAR//γ1-Cre mice. Splenic sections from these mice as well as from unimmunized control (ctrl) mice were stained for GC B cells (PNA; blue) and IgM+ cells (IgM; brown). Slices were analyzed as described in Figure 2B. (C) Left graph shows the percentages of CD23lowCD43+ cells within the fraction of reporter-positive (CAR+, hCD2+) lymphocytes 5 and 14 days postimmunization in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre (hCD2+) and CAR//γ1-Cre (CAR+) mice. Right graph shows the percentages of CD138+B220low PBs and PCs in the fraction of reporter-positive (CAR+, hCD2+) lymphocytes. Corresponding gating strategies are shown in supplemental Figure 11A. (D) Upper row: NP-IgM as well as total (NP13) and high-affinity (NP4) NP-specific IgG1-secreting PCs were determined by ELISpot analysis 14 days postimmunization using splenocytes from the 2 genotypes. Lower row: serum titers of the indicated antibodies were measured by ELISA 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG. (E) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre and CAR//γ1-Cre mice 5 and 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG and unimmunized (n.i.) ctrl mice were stained for GC B cells (GL7; green), B cells (B220; red), and PBs (IRF4; cyan). Images of immunofluorescences were obtained with the Leica TCS SP5 II with an 8-kHz resonant scanner and HCX PL APO CS 20× objective and LAS AF software. (F) Percentage of IRF4+ cells in the fraction of reporter-positive centroblasts (CBs) (CXCR4highCD86low) and CCs (CXCR4lowCD86high) was determined 14 days postimmunization. Graph compiles the percentages of IRF4+ cells in CBs and CCs from different experiments. Gating strategy of reporter+ CB and CC as well as IRF4+ cells is shown in supplemental Figure 12B. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

CD30 signaling enhances PC differentiation upon TD immunization with NP-CGG. (A) Displayed are the percentages of reporter-positive lymphocytes, CD38lowCD95high reporter-positive GC B cells, and NP+ reporter-positive GC B cells in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice and CAR//γ1-Cre upon NP-CGG immunization at the indicated time points. Gating strategy of reporter-positive lymphocytes, GC B cells, and NP+ GC B cells, as well as graphs compiling values of different experiments including the statistics, is shown in supplemental Figure 10A-C. (B) GCs were clearly visible 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre and CAR//γ1-Cre mice. Splenic sections from these mice as well as from unimmunized control (ctrl) mice were stained for GC B cells (PNA; blue) and IgM+ cells (IgM; brown). Slices were analyzed as described in Figure 2B. (C) Left graph shows the percentages of CD23lowCD43+ cells within the fraction of reporter-positive (CAR+, hCD2+) lymphocytes 5 and 14 days postimmunization in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre (hCD2+) and CAR//γ1-Cre (CAR+) mice. Right graph shows the percentages of CD138+B220low PBs and PCs in the fraction of reporter-positive (CAR+, hCD2+) lymphocytes. Corresponding gating strategies are shown in supplemental Figure 11A. (D) Upper row: NP-IgM as well as total (NP13) and high-affinity (NP4) NP-specific IgG1-secreting PCs were determined by ELISpot analysis 14 days postimmunization using splenocytes from the 2 genotypes. Lower row: serum titers of the indicated antibodies were measured by ELISA 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG. (E) Splenic sections from LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre and CAR//γ1-Cre mice 5 and 14 days after immunization with NP-CGG and unimmunized (n.i.) ctrl mice were stained for GC B cells (GL7; green), B cells (B220; red), and PBs (IRF4; cyan). Images of immunofluorescences were obtained with the Leica TCS SP5 II with an 8-kHz resonant scanner and HCX PL APO CS 20× objective and LAS AF software. (F) Percentage of IRF4+ cells in the fraction of reporter-positive centroblasts (CBs) (CXCR4highCD86low) and CCs (CXCR4lowCD86high) was determined 14 days postimmunization. Graph compiles the percentages of IRF4+ cells in CBs and CCs from different experiments. Gating strategy of reporter+ CB and CC as well as IRF4+ cells is shown in supplemental Figure 12B. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

Similar to LMP1/CD30//CD19-Cre mice, percentages of reporter-positive B220lowCD138+ and CD23lowCD43+ cells were higher in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice than in controls (Figure 6C; supplemental Figure 11A). All CD23lowCD43+ cells had a non-GC phenotype, whereas B220lowCD138high cells were elevated both in the GC and non-GC B cell fractions (supplemental Figure 11B). All B220lowCD138+ cells were CD23lowCD43+ and expressed low levels of CD19, in accordance with a PB/PC phenotype (supplemental Figure 11C). In contrast, CD23lowCD43+ cells were either CD19+ or CD19− and therefore may have been (pre) PBs or reporter-positive B1 cells (supplemental Figure 11C). These data suggest that the increased percentages of B220lowCD138+ and CD23lowCD43+ cells in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice were due to enhanced PC differentiation in GC B cells. Accordingly, NP-specific IgM and low-affinity IgG1 PCs in the spleens and antibody titers in the serum were higher in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice in comparison with controls, whereas high-affinity NP IgG1 PCs and titers were comparable between both genotypes (Figure 6D). These data indicate that the generation of PC-secreting low-affinity antibodies was enhanced in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice. In contrast, generation of memory B cells was rather decreased in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice, as indicated by lower percentages of reporter-positive IgG1+ cells (supplemental Figure 11D). Furthermore, the remaining IgG1+ B cells in LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice expressed lower levels of IgG1 at the cell surface than controls, suggesting an incipient PC differentiation.37 Because we observed the strong and fast upregulation of IRF4 upon CD40 stimulation in vitro, we tested whether LMP1/CD30 expression enhanced PC differentiation through upregulation of IRF4. LMP1/CD30 expression did not lead to higher IRF4 expression levels in any reporter-positive lymphocytes (data not shown), but it did lead to a higher percentage of IRF4+ cells (supplemental Figure 12A). Interestingly, the percentage of IRF4+ cells was higher in the fractions of both CBs and CCs (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 12B). Five days after immunization, IRF4+ B cells were localized mainly at the T-/B-cell border, suggesting that they originated from early GCs, as described by Zhang et al38 (Figure 6E). Fourteen days postimmunization, IRF4+ B cells were detected at the edge of GCs or follicles, which suggests that these cells were going to exit the GC reaction (Figure 6E). These data suggest that LMP1/CD30 expression facilitated the generation of IRF4+ B cells in the GC. Interestingly, CD30 expression was higher on reporter-positive GCs and memory B cells (CD38+IgG1+) as well as on CD38+IgG1− cells from LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice in comparison with control mice, suggesting that LMP1/CD30 influenced either the CD30 stability or expression of endogenous CD30 if it was induced in GC B cells (supplemental Figure 13A-B). Thus, in LMP1/CD30//Cγ1-Cre mice, both physiological CD30 stimulation and LMP1/CD30 expression might influence the differentiation of GC B cells. Furthermore, we detected in mutant and control mice a subpopulation of CD30highIgG1+ cells, most likely corresponding to activated memory B cells.

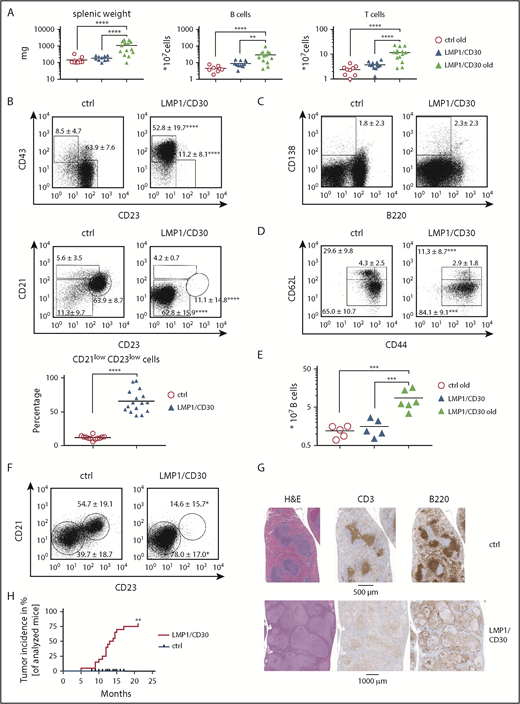

Lymphomas with B1-like/PB phenotype arise in spleen and PerC of LMP1/CD30 mice

Next, we were interested to investigate whether chronic CD30 signaling had oncogenic potential in B cells. Our results suggest that upon antigenic stimulation, chronic CD30 signaling resulted in expansion of B1 cells and PBs, which displayed enhanced proliferation as indicated by increased Ki-67 levels (supplemental Figure 14A). To test whether the expansion of B1 cells and PB cells led to lymphoma development, we aged cohorts of mice. LMP1/CD30 mice were analyzed together with age-matched controls when they showed first signs of morbidity (supplemental Figure 14B). Compared with young LMP1/CD30 mice and old control mice, aged LMP1/CD30 mice had increased splenomegaly, with elevated B- and T-cell numbers (Figure 7A). A high percentage of B cells displayed the phenotype B220lowCD21lowCD23lowCD43+ and were either CD5+ or CD5− (Figure 7B; supplemental Figure 14C) in accordance with a B1a, B1b, or PB phenotype. Most B cells were CD138− but expressed higher levels of IRF4 compared with age-matched control B cells (Figure 7C; supplemental Figure 14D). T cells were highly activated and shifted to an effector memory T-cell phenotype (Figure 7D). In addition, B1b cells were expanded in the PerC (Figure 7E; supplemental Figure 14E), and the B220lowCD21lowCD23low population was enriched in the blood (Figure 7F). Histopathological examination of the spleen revealed a disrupted structure, nodular infiltration of the white pulp by lymphocytes, and many intermingled blasts as well as diffuse infiltration of the red pulp (Figure 7G). Other samples showed confluent sheets of blasts. Approximately 80% of mice developed monoclonal lymphomas (Figure 7H; supplemental Table 3). Finally, we tested whether AID, which may induce misguided somatic hypermutation or class switch recombination and thereby contributes to lymphomagenesis, was upregulated in LMP1/CD30-expressing B cells. However, AID was comparably expressed in LMP1/CD30 and control B cells. Taken together, because in LMP1/CD30 mice the GC reaction was impaired and LMP1/CD30-expressing B cells did not aberrantly induce AID, we suggest that lymphomas arose from B cells with unmutated immunoglobulin genes. The origin of these lymphomas was most likely PBs that arose either spontaneously or during TI immune responses and were continuously stimulated by the constitutive active CD30 signal.

Lymphomas with a B1-like phenotype arise in the spleen and PerC of aged LMP1/CD30 mice. (A) Splenic weights and B- and T-cell numbers in the spleen of aged LMP1/CD30 mice compared with old control (ctrl) mice and young LMP1/CD30 mice. (B) Representative flow cytometric analyses of splenic B cells (CD19+) for CD43/CD23 and CD21/CD23 surface expression. Graph compiles the percentages of the CD21lowCD23low population of aged mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic B cells to determine the percentage of PCs (B220lowCD138+). Numbers represent means and standard deviations (SDs). (D) T cells in the spleen of aged mice were analyzed to determine the percentages and SDs of naïve T cells (CD62LhighCD44low), central memory T cells (CD62LhighCD44high), and effector memory T cells (CD62lowCD44+). (E) Diagram showing total B-cell numbers in the PerC. (F) Flow cytometric analysis of the CD21lowCD23low population in blood B lymphocytes (CD19+). Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots indicate mean and SD values of the percentages of the gated populations. (G) Hematoxylin and eosin staining as well as anti-B220 (B cells) and anti-CD3 (T cells) immunohistochemistry of spleen sections of an aged ctrl and LMP1/CD30 mouse. Sections were scanned with an AxioScan.Z1 digital slide scanner (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 20× magnification objective (EC Plan-Neofluar 20×/0.50; Zeiss) and a Hitachi HV-F202SCL 3CCD camera. Imaging acquisition was performed using ZEN 2.3 SP1 blue edition imaging software (Zeiss) and NetScope Viewer Pro (Net-Base Software GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). (H) Kaplan-Meier curve of lymphoma development in LMP1/CD30 mice. Significance of lymphoma development was calculated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

Lymphomas with a B1-like phenotype arise in the spleen and PerC of aged LMP1/CD30 mice. (A) Splenic weights and B- and T-cell numbers in the spleen of aged LMP1/CD30 mice compared with old control (ctrl) mice and young LMP1/CD30 mice. (B) Representative flow cytometric analyses of splenic B cells (CD19+) for CD43/CD23 and CD21/CD23 surface expression. Graph compiles the percentages of the CD21lowCD23low population of aged mice. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of splenic B cells to determine the percentage of PCs (B220lowCD138+). Numbers represent means and standard deviations (SDs). (D) T cells in the spleen of aged mice were analyzed to determine the percentages and SDs of naïve T cells (CD62LhighCD44low), central memory T cells (CD62LhighCD44high), and effector memory T cells (CD62lowCD44+). (E) Diagram showing total B-cell numbers in the PerC. (F) Flow cytometric analysis of the CD21lowCD23low population in blood B lymphocytes (CD19+). Numbers in the fluorescence-activated cell sorting plots indicate mean and SD values of the percentages of the gated populations. (G) Hematoxylin and eosin staining as well as anti-B220 (B cells) and anti-CD3 (T cells) immunohistochemistry of spleen sections of an aged ctrl and LMP1/CD30 mouse. Sections were scanned with an AxioScan.Z1 digital slide scanner (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 20× magnification objective (EC Plan-Neofluar 20×/0.50; Zeiss) and a Hitachi HV-F202SCL 3CCD camera. Imaging acquisition was performed using ZEN 2.3 SP1 blue edition imaging software (Zeiss) and NetScope Viewer Pro (Net-Base Software GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). (H) Kaplan-Meier curve of lymphoma development in LMP1/CD30 mice. Significance of lymphoma development was calculated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P = .001, ****P < .0001.

Discussion

Until now, the contribution of CD30 signaling to lymphoma development and its function in B-cell physiology were poorly understood. Studies in normal B cells were hampered by low numbers of CD30+ B cells in vivo, and CD30-deficient mice did not reveal a clear phenotype, probably because of the redundancy of tumor necrosis factor receptor signaling in vivo. We chose an alternative approach by studying the effect of constitutively active CD30 signaling in B cells. Here we provide evidence that chronic CD30 signaling triggered the expansion of B1 cells and PBs, resulting in B-cell lymphoma development in aged mice.

B1 cell and PC expansion in young LMP1/CD30 mice correlated well with expression data showing the upregulation of CD30 in B1 cells and PC progenitors.39 Physiologically, some activated T cells in the spleen and PerC express CD30L40 and might stimulate B1 cells, resulting in their proliferation and PC differentiation. B1 cells are known producers of natural antibodies of the IgM and IgG3 subtypes and are a major source of IgA antibodies.35,41 Thus, the elevated total antibody titers in LMP1/CD30 mice may have resulted from higher titers of natural antibodies and IgA antibodies produced by LMP1/CD30-expressing B1 cells as well as enhanced TI immune responses. Similar percentages of IgA+ PCs in the intestine in mutant and control mice suggest that the elevated IgA titers in LMP1/CD30 mice were generated from B1 cells in a GC-independent manner.

We suggest that costimulation of the BCR and CD40, as occurs during initiation of GCs and during positive selection of CCs, leads to the upregulation of CD30. CD40 signaling is essential for initiation of GCs, but enhanced or prolonged CD40 stimulation blocks the GC formation.24 CD30/CD40 costimulation at the initiation of the GC reaction, as occurs in LMP1/CD30 mice, may block the development of GCs by amplifying signals, thereby driving cells into the direction of EF PC differentiation.

In GCs, PC differentiation seems to be initiated in some CCs.37 Recently, Weniger et al12 provided evidence that CD30+ GC B cells represented positively selected CCs, which returned to the dark zone to undergo additional rounds of proliferation and hypermutation. In LMP1/CD30//γ1-Cre mice, the percentage of IRF4+ B cells was clearly increased in both CBs and CCs. IRF4+ cells may also arise in the light zone, when LMP1/CD30-expressing CCs receive a CD40 signal from T cells in the process of positive selection. Like CD30+ B cells, they may migrate back to the dark zone but are unable to switch off the CD30 signal and therefore prematurely leave the GC as IgM PCs or low-affinity IgG1 PCs. After induction of LMP1/CD30 in GC B cells, increased numbers of IRF4+ blasts were detected at the edge of the GC and B-cell follicles. In human tonsils of healthy patients, CD30+IRF4+ B-cell blasts have been described as located in the same area.10 It is still unclear whether CD30+IRF4+ EF blasts in humans originate from CD30+ positively selected CCs or from activated memory B cells. Our data suggest that at least some CD30+ GC B cells leave the GC and differentiate to CD30+IRF4+ EF blasts. Interestingly, Weniger et al12 found that STAT3-, STAT6-, and NF-κB–regulated gene sets were significantly enriched in CD30+ EF blasts, suggesting that these cells were triggered by CD30L-expressing T cells. This results in activation of the same signaling pathways as in LMP1/CD30-expressing B cells. CD30+ EF blasts are highly proliferative. Physiologically, the CD30 and other costimulatory signals are switched off after some rounds of division, and the cells most likely start to differentiate to PCs. In contrast, CD30 signaling is constitutively active in LMP1/CD30-expressing B cells, resulting in enhanced proliferation of PBs. In humans, deregulated CD30 signaling may occur during chronic B-cell activation, where increased numbers of CD30+ B lymphocytes are continuously stimulated by infiltrating T cells. Large numbers of CD30+ B cells are found upon EBV infections and in some patients with rheumatoid arthritis developing an atypical lymphoproliferative disease. The expanded CD30+ B lymphocytes are localized in the interfollicular region, often in combination with PCs, PBs, and infiltrating T cells.42-46 Interestingly, directly after infectious mononucleosis, the risk for HL is increased. Moreover, lymphoproliferative diseases, occuring upon EBV reactivation or in rheumatoid arthritis patients, may proceed to DLBCL.43,47 This corroborates our finding that chronic CD30 signaling of B lymphocytes is a predisposing factor for B-cell lymphoma development. Similarities in expression profiles of HL and some DLBCLs with CD30+ EF blasts suggest that CD30+ EF blasts are the progenitor cells for CD30+ lymphomas. Furthermore, hyperactivation of the JAK/STAT and NF-ĸB signaling pathways is often found in CD30+ DLBCL and HL,48 indicating that deregulation of these signaling pathways may be a predisposing factor for B-cell lymphomagenesis. There are several parallels between our mouse model and human diseases with elevated numbers of CD30+ EF blasts. (1) In the premalignant state, increased numbers of immunoblasts are localized in the interfollicular region. (2) Like CD30+ EF blasts, activated LMP1/CD30 B cells show enhanced JAK/STAT and NF-κB signaling. (3) The high IRF4 levels in lymphomas of LMP1/CD30 mice suggest that they derive from PBs rather than B1 cells. (4) In some cases, the histology of LMP1/CD30-expressing lymphomas was reminiscent of DLBCL. We therefore conclude that our mouse model reflects lymphomagenesis in patients with chronic B-cell activation, resulting in increased numbers of CD30+ B cells. However, our data also indicate that chronic CD30 signaling alone is not sufficient to induce lymphomagenesis. Indeed, all described tumors mainly consisted of a monoclonal cell population, indicating that they derived from single secondary mutation events. It will be interesting to determine which mutations cooperate with chronic CD30 signaling to drive lymphomagenesis.

Please e-mail the corresponding author, Ursula Zimber-Strobl (strobl@helmholtz-muenchen.de), regarding requests for original data.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Krisztina Zeller for excellent technical assistance and the animal facility of the Helmholtz Center and the animal caretakers for excellent housing of the mice; Eckhard Podack for kindly providing the vector pBmgNeo CD30-5.2, which contained the full-length CD30 complementary DNA clone; and Ralf Küppers for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work benefitted from data assembled by the ImmGen Consortium.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (111426), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TRR54, A1, DFG ZI1382/4-1, and SFB1243, A12, A13), and the Jose Carreras Stiftung (DJCLS R 13/02).

Authorship

Contribution: S.S., P.F., A.P., M.L., S.E., and G.S. performed experiments; L.K., A.-I.S., and A.F. performed and evaluated histology; R.K. generated LMP1/CD30stopfl mice; L.J.S. performed in silico analysis; M.S.-S., L.J.S., and U.Z.-S. designed experiments; and S.S., P.F., L.J.S., and U.Z.-S. prepared and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ursula Zimber-Strobl, Research Unit Gene Vectors, Helmholtz Center Munich, Marchioninistr 25, 81377 Munich, Germany; e-mail: strobl@helmholtz-muenchen.de.

REFERENCES

Author notes

S.S., P.F., L.J.S., and U.Z.-S. contributed equally to this work.