In this issue of Blood, Klanova et al1 report, from one of the largest prospective datasets in untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLCBL), an integrated clinical and biological risk model that meaningfully delineates risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse.

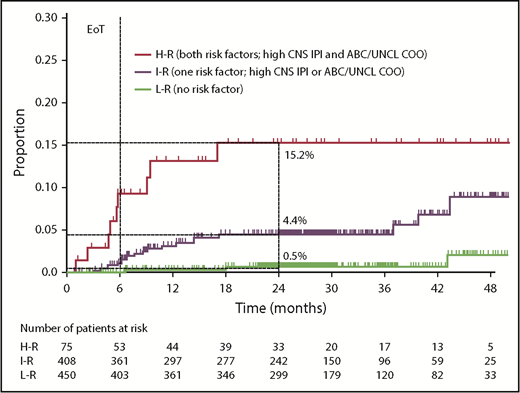

Risk of CNS relapse by CNS-IPI and COO (CNS-IPI-C) in the COO available population (n = 933). EoT, end of treatment; H-R, high risk; I-R, intermediate risk; L-R, low risk; UNCL, unclassified. See Figure 2 in the article by Klanova et al that begins on page 919.

Risk of CNS relapse by CNS-IPI and COO (CNS-IPI-C) in the COO available population (n = 933). EoT, end of treatment; H-R, high risk; I-R, intermediate risk; L-R, low risk; UNCL, unclassified. See Figure 2 in the article by Klanova et al that begins on page 919.

Notwithstanding improvements in treatment of established CNS relapse in DLBCL,2 such events are devastating for patients and frequently associated with neurocognitive disability and short survival times. Thus, efforts have focused on identifying those patients at highest risk of CNS progression who may benefit from CNS prophylaxis, recognizing that both intrathecal and systemic prophylactic strategies inherently confer additional toxicity risks. This remains a difficult and somewhat controversial area. Recent improvements in CNS relapse risk stratification have been achieved from comprehensive analyses of pooled clinical trial datasets and validated in a large population-based cohort.3 The resulting clinical risk score, termed the CNS–International Prognostic Index (IPI), has been widely adopted in clinical practice, although it is recognized that this remains insufficiently precise.4 Improvements in the positive predictive value (identifying those at highest risk) compromise sensitivity, resulting in a significant proportion of “missed” CNS events occurring in the intermediate-risk group. These limitations speak to the need for reliable biomarkers to more clearly delineate risk groups.

Klanova et al present data from the GOYA study,5 describing the impact of cell of origin (COO) by gene expression profiling, on the risk of CNS relapse. This is the first such study in the context of a prospective clinical trial that clearly demonstrates the independent predictive value of an “activated B-cell–like” (ABC) or “unclassifiable” gene expression profile on the risk of CNS relapse. Importantly, COO status retained its significance in a multivariable model incorporating existing clinical risk factors, including the CNS-IPI. Interestingly, and by contrast to retrospective population-based data,6 there was no impact of BCL2 and MYC protein coexpression on CNS relapse risk in the GOYA study on univariate or multivariable analyses. This may be influenced by a higher proportion of patients with BCL2/MYC dual expression in the GOYA study compared with the BCCA study. Notably, in the BCCA dataset,6 the impact of BCL2/MYC dual expression was modified based on COO (higher impact in the ABC group) and higher CNS-IPI scores. Importantly, in this larger prospective dataset from the GOYA study, both COO and CNS-IPI (but not BCL2/MYC dual expression) were independently predictive in a multivariable model.

On a similar theme, the coexistence of an MYC and BCL2 translocation by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH; so-called double-hit DLBCL) has, in retrospective analyses, been associated with increased risk of CNS relapse and accordingly has had some influence on clinical practice. However, this issue remains controversial with clinical and pathological case selection bias likely to be confounding factors. Although this particular question cannot be considered resolved by the Klanova et al data, it is notable that, of the 560 patients with evaluable FISH data in the GOYA study, 20 had double-hit DLBCL of whom only 1 experienced a CNS relapse. This observation is consistent with the BCCA data6 in which the risk of CNS relapse for patients with double-hit DLBCL was 4.5% at 2 years. Moreover, this aligns with expectations based on the COO data presented by Klanova et al, given that patients with double-hit DLBCL fall almost exclusively within the germinal center B-cell–like COO group.

By combining the 2 factors found to be significant in a multivariable model, Klanova et al created a modified risk-stratification model (1 point for high CNS-IPI, 1 point for ABC or unclassified COO) termed the CNS-IPI-C (see figure). This model permitted identification of a group comprising almost half the entire cohort with a very low risk of CNS relapse. Conversely, 8% of patients fell into the high-risk (2 point) category with a predicted 15.2% risk of CNS relapse at 2 years. The intermediate-risk group had a predicted CNS relapse risk close to that anticipated in an unselected DLBCL cohort.

Based on observations in primary CNS DLBCL, in which biallelic loss of CDKN2A and mutations of MYD88 and CD79B are very frequent, Klanova et al performed exploratory mutational profiles on a proportion of patients. Interestingly, CDKN2A loss and MYD88 mutation were the most commonly observed alterations in patients with CNS relapse in the GOYA study. CDKN2A loss was associated with higher risk of CNS relapse independent of clinical factors, although this association was weakened by COO status.

This is an important paper contributing to a difficult clinical issue. Reliable prediction of CNS relapse in patients with DLBCL (and thereby appropriate intervention with preventative strategies) has been an imperfect and contentious issue based on relatively crude clinical algorithms. Although a number of unanswered questions remain, the COO status appears to be an important biological predictor of CNS relapse that could further refine the widely employed CNS-IPI score. However, before this modified risk-stratification model can be incorporated into routine clinical practice, validation of the CNS-IPI-C in an independent series of DLBCL is required.

How will further improvements in specificity and sensitivity of CNS relapse risk prediction models be achieved? Certainly, there is great potential for further learning from biological studies on both primary and secondary CNS lymphoma tissue biopsies, together with the identification of relevant soluble factors (chemokines and microRNAs) in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Looking ahead, one could envisage a hierarchical risk model, whereby baseline clinical and pathobiological data allow distillation to a group of patients, in whom neuroaxis imaging and CSF evaluation are warranted, allowing identification of a group who warrant intensive CNS prophylaxis, while confidently assigning the majority of patients to a low-risk category. Given the low absolute number of CNS events in DLBCL, even within large studies like GOYA, such progress will surely rely on international collaborative efforts.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.P.F. received research funding from AbbVie, Adienne, Gilead, and Roche; received advisory board honoraria from AbbVie, Adienne, Atarabio, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche, Sunesis, and Takeda; and received travel support from AbbVie, Celgene, Gilead, Janssen, Roche, and Takeda.