Introduction:

Neurocognitive deficits are a well-known complication in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) and are often associated with overt stroke and silent infarctions. However, cognitive deficits may be seen in patients even without apparent MRI findings as compared to non-affected controls. Studies have also shown the impact of socioeconomic status and parental education on school retention and cognition in patients with SCD. More specifically, rates of retention and special education service use through either an Individualized Education Plan (IEP, providing specialized education services) or 504 Plan (providing accommodations due to physical disability/medical diagnosis) are reported as high as 40%. However, these historical data have been limited to primarily adolescent patients. Thus, a more thorough analysis is needed to better determine the prevalence and types of academic challenges among children with sickle cell disease, particularly younger ages.

Methods:

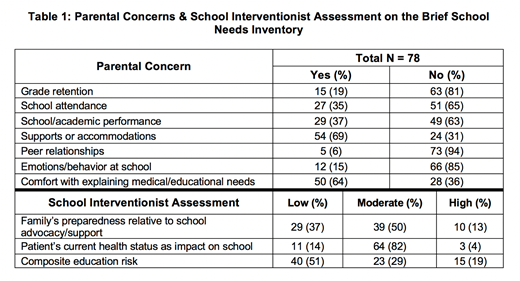

The Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center's Comprehensive Sickle Cell Clinic includes a school intervention program. This program includes 1-2 full time school teachers who engage directly with patients, parents, and school staff to ensure the provision of adequate school-based services and to address specific challenges or concerns. Children with SCD are referred to the school interventionist by the clinical team (including both medical and psychosocial providers) for any school-related concern. The interventionist completes the Brief School Needs Inventory (BSNI), a thirty-item tool that determines a patient's educational risk based on academic and psychosocial history and parental responses. The BSNI provides a numeric score from 0-20 and a categorical risk of 1 (low risk) to 3 (high risk).

In this retrospective review, the BSNI for all patients with SCD completed during the 2018-2019 school year were reviewed. The prevalence of the receipt of special education services (SES), grade retention, neuropsychological testing, and number of school absences were captured. Basic demographic and disease-related data, including zip code, patients' disease history, use of disease-modifying therapy, and any notable brain MRI findings were also recorded. Median household income was extrapolated from the zip codes based on 2017 US Census Bureau reporting (the most recently published year).

Results:

A total of 78 patients (58 HbSS, 17 HbSC, 3 HbS/β+-thalassemia) completed the BSNI for the 2018-19 academic year; an additional 15 children were also referred but did not complete the evaluation. Nearly all (95%) of patients with HbSS were receiving disease-modifying therapy (hydroxyurea or transfusions); 41% of patients with MRIs showed abnormal findings. Median age was 9 years (range 14 months - 19 years, preschool - post-secondary education). Nineteen percent of patients lived in a zip code with a median household income below the federal poverty level ($25,750). The mean BSNI score was 7.6±5.5; 27 patients were deemed low risk, 32 moderate risk, and 19 high academic risk by the BSNI (Table 1). A majority (50%) of parents responded with concerns both with obtaining support/accommodations for their child and explaining their child's medical needs to the school. Of 59 recorded, 24% of patients had had at least 16 absences in the prior year. Despite the diagnosis of SCD for all patients, only 21% had established 504 medical plans. Academic concerns were common with 20% of referred children reporting an IEP, 14% of patients with a history of grade retention, and an additional 10% with concerns for possible retention.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of academic difficulties and challenges is high amongst patients with SCD even in the elementary to middle school years, with rates of grade retention ~20% as compared to the national average of <2-6%. Parents of children with SCD report their greatest concerns as obtaining accommodations for their child and explaining their child's medical needs to school personnel. Most parents and schools are inadequately prepared or resourced to identify and address academic and medical needs in the school-based setting, resulting in persistent academic struggles for many children with SCD. A school intervention program is a feasible way to facilitate interaction between parents and schools to optimize educational experiences and outcomes.

No relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.