In this issue of Blood, Rosen et al evaluate the discordance in factor VIII (FVIII) activity after adenoviral-associated vector (AAV)-gene therapy between 1-stage (OS) and chromogenic-substrate (CS) assays.1

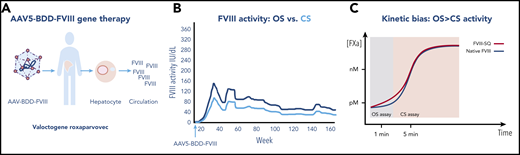

Factor VIII activity after AAV gene therapy. (A) AAV5-BDD-FVIII (valoctocogene roxaparvovec) is infused intravenously into a patient with severe hemophilia A. The vector-gene targets the hepatocyte and is expressed and secreted into the circulation. (B) Transgene-produced FVIII measured by the OS clot assay, indicated by the dark line, is 1.6-fold higher than FVIII activity measured by CS assay, indicated by the light line. (C) Kinetic bias leads to higher FVIII activity by OS than CS activity by gene-produced FVIII compared with native (wild-type) FVIII, as the former, but not the latter, accelerates early factor Xa formation, leading to earlier visible clot formation in the OS assay, which is read within the first 1 to 2 minutes of the coagulation reaction, whereas gene-produced FVIII and native FVIII show similar clot formation in the CS assay, which measures FVIII activity by color change after a 5-minute incubation, and is unaffected by the early reaction resulting in lower FVIII activity than by the OS assay. For panel C, see Figure 6 in the article by Rosen et al that begins on page 2524.

Factor VIII activity after AAV gene therapy. (A) AAV5-BDD-FVIII (valoctocogene roxaparvovec) is infused intravenously into a patient with severe hemophilia A. The vector-gene targets the hepatocyte and is expressed and secreted into the circulation. (B) Transgene-produced FVIII measured by the OS clot assay, indicated by the dark line, is 1.6-fold higher than FVIII activity measured by CS assay, indicated by the light line. (C) Kinetic bias leads to higher FVIII activity by OS than CS activity by gene-produced FVIII compared with native (wild-type) FVIII, as the former, but not the latter, accelerates early factor Xa formation, leading to earlier visible clot formation in the OS assay, which is read within the first 1 to 2 minutes of the coagulation reaction, whereas gene-produced FVIII and native FVIII show similar clot formation in the CS assay, which measures FVIII activity by color change after a 5-minute incubation, and is unaffected by the early reaction resulting in lower FVIII activity than by the OS assay. For panel C, see Figure 6 in the article by Rosen et al that begins on page 2524.

This is the golden age of novel therapies for hemophilia. For those with hemophilia A, an X-linked disorder characterized by deficient or defective FVIII, gene therapy holds the promise to reduce disease burden and improve quality of life. Data from ongoing clinical trials indicate a person with hemophilia A who receives AAV-based gene therapy may expect FVIII levels to be restored into the therapeutic range sufficient to reduce bleeds, decrease factor use,2,3 and prevent deaths, especially in resource-limited settings where factor is scarce.

In recent gene therapy trials of valoctocogene roxaparvovec,2,3 an AAV containing B-domain-deleted (BDD) FVIII transgene (AAV5-FVIII-SQ), a discrepancy has been recognized in transgene-produced FVIII activity by the OS clotting assay and the CS assay. FVIII activity is the major efficacy end point of gene therapy because it measures hemostatic efficacy and predicts bleed severity.4 Further, FVIII activity is the basis for comparison between FVIII products, so it is critical as well as practical to understand why OS and CS are discordant.

To analyze this discrepancy, Rosen et al first confirmed that FVIII activity is higher by OS than CS in patients receiving gene therapy (1.6-fold higher), whereas FVIII in recombinant BDDFVIII (spiked samples) and controls (native FVIII) are comparable in OS and CS assays. This finding suggested that the discordance arises in the OS assay. The authors next conducted a field study at 13 different study sites, comparing assays using OS kits with 7 different activated partial thromboplastin time reagents with 3 different surface activators, and 6 different CS kits with 4 different chromogenic FXa substrates, in >1000 samples from AAV5-BDD-FVIII gene therapy recipients. They confirmed the OS to CS ratio discrepancy, which ranged from 1.292 to 2.013, but show the assay, reagents, and laboratories had no effect on the OS:CS discrepancy.

Thrombin generation assays5 confirmed these studies. The authors demonstrated that although peak thrombin and estimated thrombin potential are comparable for transgene and recombinant FVIII, the lag time and time to peak thrombin level are shorter for OS than CS, a finding consistent with a shorter time to clot formation with OS than CS in the previous kinetic assays. Subsequent studies excluded other potential causes for the difference, including sequence polymorphisms and codon optimization. The species of the originating cell type may contribute to the assay discordance between transgene FVIII, which is produced in human hepatocytes (hepG2 cells), and recombinant FVIII, which is produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells, but more studies are needed to understand cell-type-specific modifications during FVIII synthesis or secretion. In clinical studies, the authors showed that joint bleed frequency, the major clinical efficacy measure of gene therapy, is highly correlated with FVIII activity by both CS and OS, confirming the clinical relevance of each assay.

To investigate kinetics in the OS assay, Rosen et al investigated reaction kinetics in samples from 2 gene therapy recipients. They show that the higher OS than CS activity in transgene-produced FVIII, as compared with native (wild-type) FVIII, is likely caused by rapid onset of coagulation in the OS assay (see figure). The transgene-produced FVIII accelerates early FXa formation and thrombin activation leading to earlier visible clot formation in the OS assay, which is read within the first 1 to 2 minutes of the coagulation reaction. By contrast, the CS assay, which measures FVIII activity in the Coatest by color intensity after a 5-minute incubation, is unaffected by the early reaction, resulting in lower FVIII activity than by OS assay. Thus, the difference between assays and samples is due to the more rapid onset of coagulation in the OS assay. The CS has been chosen as the standard for hemophilia AAV gene therapy trials, with its broad utility for non-native FVIIIs and conservative measure of hemostasis allowing efficacy comparisons between various FVIII products. It is noteworthy that many coagulation laboratories do not perform chromogenic assays. Thus, one consideration may be the development of an OS/CS conversion to allow for activity interpolation in the CS assay, but this would require a thorough, laboratory-specific evaluation.

Finally, although these studies involve in vitro measures of transgene-produced FVIII activity, many challenges remain in hemophilia gene therapy. Identifying the optimal factor level for efficacy, assuring safety, and ultimately understanding durability and the reason factor levels fall with time are of critical importance. The recent decision by the US Food and Drug Administration to require longer term data on AAV-BDD-FVIII gene therapy recipients should provide much needed insight. Going forward, it will be critical to routinely obtain liver biopsies,6 which are performed safely in hemophilia patients by the transjugular route,7 to improve our understanding of the intracellular processes involved after the gene DNA is directed into the nucleus, assumes episomal configuration, and transcribes RNA and translates FVIII protein. What level of integration occurs? What is the cause of periodic transaminase elevation? Why are factor levels so variable, even with the same vector-gene dose within the same study? Does endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and ER protein misfolding in hepatocytes occur in gene therapy recipients, as observed in mice after receiving AAV-BDD-FVIII,8 and does FVIII accumulate in an aggregated, amyloid-like globular form in the ER9 and contribute to variability and reduced durability? Measure for measure, the next studies to advance the field of hemophilia gene therapy are daunting.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.