In this issue of Blood, Reinke et al1 describe the rapid clinical and histologic response to antiprogram death-1 (PD1)–based first-line therapy in patients with early-stage unfavorable classic Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL), without the induction of a cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell–mediated immune response.

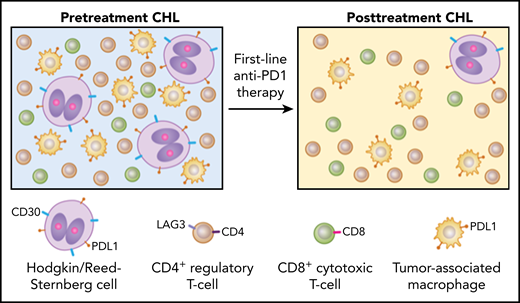

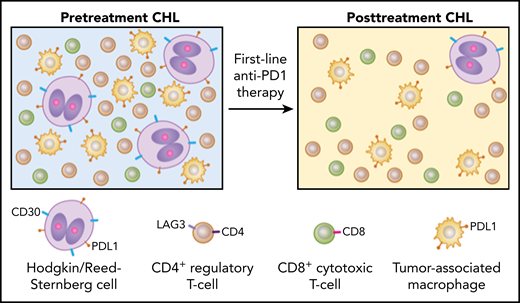

Anti-PD1 blockade as first-line therapy in early-stage unfavorable CHL shows distinct differences in clinical and histologic response. CHL exhibits rare malignant HRS cells in a TME enriched for inflammatory cells, particularly CD4+LAG3+ Tr1s, PDL1+ TAMs, and fewer CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (left). Biopsies following first-line anti–PD1-based therapy in early-stage unfavorable CHL patients show dramatic decrease in CD30+PDL1+ HRS cells along with depletion of Tr1 cells and PDL1+ TAMs, especially in the vicinity of HRS cells, with no expansion of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (right). These findings underscore significant differences in the TME composition of pre- and posttreatment CHL and favor withdrawal of survival factors rather than cytotoxic immune responses as the most likely mechanism of action in first-line immune checkpoint blockade.

Anti-PD1 blockade as first-line therapy in early-stage unfavorable CHL shows distinct differences in clinical and histologic response. CHL exhibits rare malignant HRS cells in a TME enriched for inflammatory cells, particularly CD4+LAG3+ Tr1s, PDL1+ TAMs, and fewer CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (left). Biopsies following first-line anti–PD1-based therapy in early-stage unfavorable CHL patients show dramatic decrease in CD30+PDL1+ HRS cells along with depletion of Tr1 cells and PDL1+ TAMs, especially in the vicinity of HRS cells, with no expansion of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (right). These findings underscore significant differences in the TME composition of pre- and posttreatment CHL and favor withdrawal of survival factors rather than cytotoxic immune responses as the most likely mechanism of action in first-line immune checkpoint blockade.

Hodgkin lymphoma has remained an enigma since its first description in 1832. Histologically, this lymphoma is characterized by rare malignant Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells that are ensconced in a rich inflammatory tumor microenvironment (TME). This TME contains a variety of cell types including CD4+ T cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), eosinophils, B cells, plasma cells, and stromal cells. The HRS cells skillfully exploit the TME to subvert host immune surveillance. By downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class 1 expression, they avoid recognition and killing by effector T cells. The integrity of the TME and the crosstalk among its constituents are therefore vital for the survival of HRS cells.

CHL is a prototypical example of the concept that tumor-intrinsic genetic alterations are responsible for sculpting the TME.2 The vast majority of CHL harbor chromosomal alterations at 9p24.1 that lead to the overexpression of PD1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2.3 These genetic alterations provide the substrate for anti–PD1-based therapies, with CHL emerging at the forefront of cancers that are exquisitely sensitive to this treatment approach. Although PD1 blockade leads to impressive initial clinical responses, most patients with CHL eventually experience disease relapse.4-6 The mechanisms that underlie HRS cell recognition and destruction after PD1 blockade and the subsequent development of treatment resistance are critical open questions.

Effective blockade of inhibitory checkpoint receptors in solid tumors such as melanoma and carcinoma is mediated through an adaptive T-cell immune response. Yost et al7 recently reported that this T-cell response ensues primarily from recruitment of distinct clonal repertoires of CD8+ T cells that express gene signatures of high proliferation, chronic activation, and exhaustion. To maintain a sustained treatment response, recruitment of novel T-cell clones provides an advantage over reliance on a limited immune capacity to reinvigorate preexisting intratumoral exhausted T cells. Although the exact mode of T-cell recruitment requires further investigation, this observation provides an attractive hypothesis for tumors that contain an inflammatory microenvironment such as CHL. In support of this consideration, PD1 blockade was found to be most efficacious in CHL patients who had a rich repertoire of baseline T-cell receptor diversity and expansions of novel T-cell clones during treatment.8

Patients with early-stage unfavorable CHL are typically treated with combined-modality chemotherapy with involved-site radiation. Whereas, PD1 blockade has shown efficacy in patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) CHL, experience in the first-line setting has thus far been limited. Recently, Brockelmann et al9 reported excellent progression-free survival and high rates of complete remission after first-line treatment with the anti-PD1 agent nivolumab in patients with CHL with early-stage unfavorable disease. To gain insight into this clinical response, Reinke et al compared tissue biopsies and blood samples at diagnosis with repeat biopsies obtained after the first few days of anti-PD1 therapy. Biopsies from a separate cohort of patients with r/r CHL with progressive disease during anti-PD1 therapy were also studied.

Rebiopsy samples after first-line PD1-blockade showed a remarkably rapid disappearance of HRS cells along with CD4+LAG3+ regulatory T (Tr1) cells and PDL1+ TAMs in the TME (see figure). Up to 50% of biopsies had no HRS cells based on histology and immunohistologic assessment of CD30, which was further confirmed by gene expression profiling (GEP) and digital whole slide imaging. The patients also reported resolution of clinical symptoms. The depletion of Tr1 cells and TAMs was particularly prominent in the immediate vicinity surrounding the few remaining HRS cells. In addition, GEP analysis showed decreased expression of Tr1-related genes such as LAG3, TNFRSF8, CD25, and BATF. PDL1 was downregulated on HRS cells and to a lesser extent on TAMs, whereas PD1 expression remained unchanged. MHC class I and II expression, as well as 9p24.1 genetic alteration, showed no correlation with this early histologic response pattern. In r/r CHL biopsies, however, significant numbers of HRS cells persisted after anti-PD1 therapy. The most striking finding in the first-line treatment cohort was that no clonal T-cell expansion or cytotoxic T-cell response was detected in sharp contrast to solid tumors and r/r CHL.6-8 The lack of cytotoxic activity suggests that the observed clinical and histologic response is most likely because of the withdrawal of proinflammatory factors that are important for the survival of HRS cells and the preservation of its TME. These findings raise the intriguing possibility that a treatment naïve CHL TME is fundamentally different from that of r/r CHL.1 In the relapse setting, CHL subclones may have emerged that have acquired the capacity to remodel their TME differently and/or are less addicted to an altered TME for survival.

Genetic and epigenetic alterations that generate intratumoral heterogeneity also affect the TME and lead to divergent responses and resistance to immunomodulatory therapy. Neoepitope loss and immunoediting have been proposed as likely mechanisms that regulate intratumoral diversity. These changes are aligned with clinical observations in subsets of patients with r/r CHL, where tissue biopsies show differences in histologic growth patterns, increased numbers and confluence of HRS cells, and changes in immunophenotypic profiles that were not present in the original biopsies. In solid tumors and r/r CHL, the intrinsic ability of the tumor to continuously recruit effector T cells is essential for tumor regression and clinical response after immune checkpoint blockade.6-8 The lack of an effector T-cell response therefore raises the critical question of why withdrawal of survival factors appear to dominate first-line inhibition of the PD1–PDL1 axis in treatment-naïve CHL patients. Further investigation in larger cohorts receiving first-line immune checkpoint blockade therapy is warranted to explore this important question.

In summary, the findings reported by Reinke et al contribute another notable step forward in the understanding of the CHL TME and highlight essential differences in de novo vs recurrent disease. Although many aspects of the CHL TME remain elusive, the success of first-line immune checkpoint blockade holds promise for durable clinical response coupled with reduced toxicity in patients with CHL and other tumors with an immune infiltrated microenvironment.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.