Long-term follow-up for novel therapies is essential to confirm initial safety and efficacy data, but how often does that long-term follow-up show better results than the initial studies? In this issue of Blood, a 2-year follow-up to the HAVEN trials by Callaghan et al1 studying emicizumab for prophylaxis in severe hemophilia A with and without inhibitors has done just that.

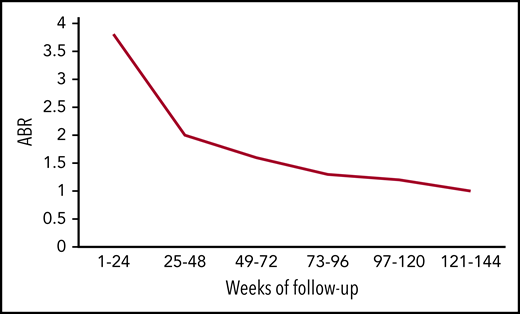

Mean ABR of all bleeds over time. The figure has been adapted from data in Table 2 in the article by Callaghan et al that begins on page 2231.

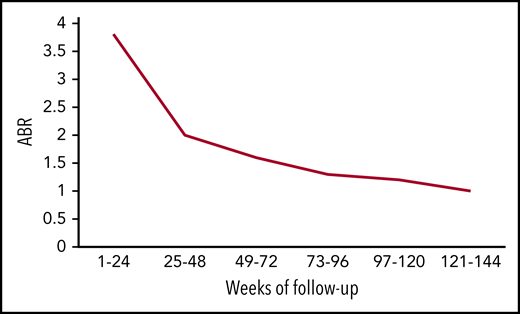

Mean ABR of all bleeds over time. The figure has been adapted from data in Table 2 in the article by Callaghan et al that begins on page 2231.

Emicizumab is a bispecific antibody that binds factors IXa and X to mimic the function of factor VIII. Its appeal comes down to 3 large breakthroughs that each on its own might have shifted patient choice. First, emicizumab is not recognized by inhibitors of factor VIII because it is NOT factor VIII. This allows it to function in patients with and without inhibitors, a clear victory for inhibitor patients who have previously had inferior therapeutic options. Second, emicizumab is administered subcutaneously, a major improvement compared with the IV route of traditional factor concentrates. Third, the half-life of 30 days is an enormous leap from 12 to 24 hours of factor VIII concentrates, including extended half-life products. However, these characteristics say little about its efficacy and safety.

The HAVEN 1 to 4 trials2-5 divided patients into randomized arms by age (<12 and 12+), inhibitor status, and dosing schedule (weekly, every other week, or every 4 weeks). Compared with the patients using factor VIII or bypass agents for prophylaxis, annualized bleeding rates (ABRs) improved with emicizumab by 79%, 99%, and 68% in HAVEN 1 to 3, respectively.

In the current update, Callaghan et al followed the patients from HAVEN 1 to 4 for 2 years and found ABR declining over time. Using pooled data between studies, the mean ABR for all bleeds fell from 3.3 in the first 24-week period to 1.0 in the final-week period (see figure). This improved trend was captured not only in ABR for all bleeds but also in the number of patients reporting zero all bleeds, 0 to 3 all bleeds, 0 to 3 target joint bleeds, and factor VIII consumption. Perhaps most striking is that bleeding rates for inhibitor patients are now on par with those of noninhibitor patients.

Activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC) consumption also declined over time, not surprisingly since the announcement that its use with emicizumab should be avoided because of thrombotic risk. This led to a diversion of aPCC to recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) for treatment of acute bleeds in inhibitor patients and may explain the slight increase in rFVIIa usage during treatment midstudy intervals (weeks 49 to 120). This diversion makes the overall decline in rFVIIa consumption more notable.

Why bleeding rates and target joints might improve over time warrants more exploration. Perhaps, a decrease in bleeding events leads to increased activity, exercise, and bone and joint health, whereas improved joint health, coming full cycle, results in further declines in bleeding. In addition, improved hemostasis may prevent recurring microbleeding and chronic inflammation in the joint space. Could these improvements in joint health eventually reset the threshold for initiation of acute hemarthrosis?

In the initial HAVEN 1 trial,2 5 inhibitor patients developed thrombotic complications, including 3 with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) when acute bleeds were treated with aPCC at higher cumulative doses (>100 U/kg/24 hours) for extended periods of time (≥24 hours). The TMAs resolved once aPCC was stopped. Most reassuring in the 2-year follow-up is that no additional thromboses or TMAs occurred after restriction of aPCC was instituted. Also, no new safety concerns appeared. However, in all the HAVEN studies, only 26 patients were age 65 or older. One of these patients suffered a myocardial infarction and was found to have coronary artery disease. Future data for patients with cardiac risk factors on emicizumab will be welcome.

What is the frequency of anti–emicizumab antibody development? In the initial HAVEN publications,2-5 the rate was 1.0% of patients (4/398), although only 2 (0.5%) of these antibodies were neutralizing, compromising the efficacy of emicizumab. With enhanced testing, 14 (3.5%) anti–drug antibodies were found, only 3 with neutralizing potential (0.8%), including 1 patient who switched back to factor VIII infusions for prophylaxis.6 Whether the enhanced test or the additional drug exposure time led to increased detection of anti-drug antibodies is unclear. The authors are planning to report a separate update regarding emicizumab’s immunogenicity. Still, these numbers seem like an improvement compared with traditional factor VIII concentrates, which stimulate anti–factor VIII inhibitor development in up to one-third of severe hemophilia A patients.

Altogether, it becomes clear why patients report improvements in quality of life and a strong preference to remain on emicizumab.7 For patients and providers cautious about accepting new advances, the work by Callaghan et al comes as a welcome addition to the previous landmark HAVEN trials. With 2 years of follow-up confirming its safety and efficacy, emicizumab should be considered the standard of care for severe hemophilia A prophylaxis in patients with and without inhibitors. With these exciting data on emicizumab and prospects for other nonfactor therapies around the corner, hemophilia care just keeps getting better.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author receives research funding from and serves on the advisory board for Genentech.