In this issue of Blood, Wang et al compare the minimal residual disease (MRD) rate and outcome of patients with CLL treated with continuous ibrutinib plus 6 cycles of rituximab (IR) with that of those treated with FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab).1 This study provides comparative data on the use of MRD in the management of CLL and emphasizes several pressing issues.

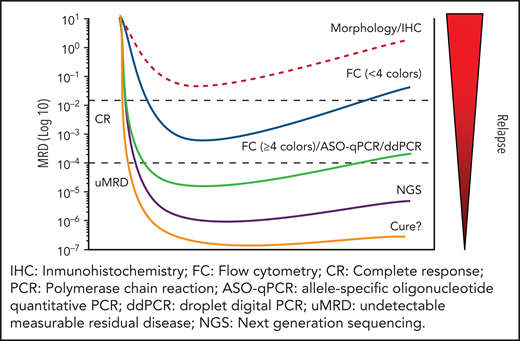

Eradicating the tumor is a necessary requisite for curing cancer; hence, there is a need for precise methods of assessing response to therapy. However, no matter how thoroughly the remission is confirmed, a large proportion of patients eventually relapse. Routine clinical, laboratory, and imaging methods do not currently detect occult residual tumor, which is referred as minimal (or, more precisely, measurable or detectable) residual disease (MRD). Methods to evaluate MRD include morphology, flow cytometry (FC), allele-specific oligonucleotide quantitative polymerase chain reaction (ASO-qPCR), droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), next-generation sequencing (NGS), and cell-free DNA analysis, each with different sensitivity (see figure).

In 2005, the importance of achieving a complete response (CR) with “negative” (unmeasurable) MRD (uMRD) as the goal of therapy in CLL was proposed.2 With the advent of chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) in treating CLL, the relevance of CR uMRD became more apparent. CIT (namely, FCR) results in an up to 83% response rate, with uMRD in 50% of patients with low-risk CLL, translating into a longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), independent of the degree of clinical remission. Notably, this includes a proportion of patients who could be considered “cured.”3,4

In the past decade, treatment of CLL has dramatically evolved from CIT to targeted agents: for example the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) ibrutinib. The CR rate at the beginning of treatment with ibrutinib is low (<20%) but improves over time, particularly in patients treated in the front-line setting, with CR rates increasing to up 34%. In some cases, MRD becomes undetectable.5 Wang et al have conducted sequential analyses of MRD (at 3, 12, 24, and 36 months) in young, previously untreated patients with CLL randomly assigned to receive either ibrutinib+rituximab (IR) (n = 354) or FCR (n = 175). The proportion of FCR-treated patients in whom uMRD <10−4 (in blood) was achieved was much higher than the proportion of those treated with IR and was associated with significantly longer PFS. In the IR arm, patients with detectable MRD did not have significantly worse PFS than those in whom MRD was undetectable; however, PFS was longer in those with MRD <10−1 compared with those with MRD levels above that threshold.

This trial convincingly validates the importance of achieving uMRD in patients with CLL treated with FCR. The results obtained with IR require more nuance, as wisely indicated by Wang et al. For example, the reasons that the clinically significant MRD threshold for IR was 10−1 are unclear, although the number of observed events, methodological problems, and the difficulties posed by subgroup analysis could be a factor.

Where do we stand on the role of MRD in patients with CLL treated with pathway inhibitors (PIs)? Drawing conclusions on the role of MRD in patients with CLL treated with PIs is difficult because of the lack of randomized studies with uniform criteria, methodology, and standardized reporting. Also, in contrast to the analysis by Wang et al, some studies have focused only on the response rate.5 Needless to say, further well-designed randomized trials are needed. At the same time, methodological issues (eg, the time and site at which MRD should be assessed; optimal MRD thresholds [perhaps therapy related?]; the role of NGS and cell-free DNA analysis in MRD detection; the impact of different forms of therapy on test sensitivity, and uniform reporting) should be addressed.6

Regarding the goal of therapy, the introduction of ibrutinib in CLL therapy challenged the CIT-driven paradigm that achieving deep CR with uMRD is a most desirable objective. The counter paradigm is that longer PFS and OS can occur without eradicating the disease. However, although ibrutinib-based therapy has significantly improved outcomes, no plateaus in PFS have been observed. Moreover, the response rate depends on treatment modality and schedule. For example, the addition of obinutuzumab to ibrutinib induced uMRD in 20% to 60% of patients, which is significantly higher than the outcome obtained with IR (below 10% of patients, when all known precautions for cross-trial comparisons were applied).7 Importantly, other targeted therapies, such as venetoclax (a selective inhibitor of BCL2), induced profound clinical remissions with uMRD in a high proportion of patients across all risk groups. Also, combinations of targeted therapies (eg, venetoclax+ibrutinib+anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies) have improved the proportion and quality of remissions (including uMRD), with a very long PFS.8,9 If confirmed, these data would reinforce rather than invalidate the “uMRD paradigm.”

Finally, to clarify the role of MRD in CLL management requires international collaboration that should include the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency as central partners. Meanwhile, the recommendation formulated by the International Workshop on CLL that MRD-guided therapy should be restricted to clinical trials remains sound.10

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.