Abstract

Glycogen storage disease type Ib (GSD-Ib) is a rare disease caused by a defect in glucose-6-phosphate translocase (G6PT/SLC37A4). Individuals with GSD-Ib more likely develop neutropenia. Neutropenia and neutrophil dysfunction in GSD-Ib have been ascribed to the intracellular accumulation of 1,5-anhydroglucitol-6-phosphate (1,5AG6P), leading to clinical repurposing of Empagliflozin, an inhibitor of the kidney sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2). By lowering serum 1,5AG6P, Empagliflozin improves absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and functions in GSD-Ib.1 It remains yet to be elucidated whether Empagliflozin affects specific changes in neutrophils' distribution of GSD-Ib patients.

Here we investigated neutrophil subsets in the peripheral blood of GSD-Ib patients before and after 3 months of Empagliflozin treatment.

Four patients (9-16 years old), harboring biallelic SLC37A4 variants and with ongoing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) treatment, were included in the study. They were clinically evaluated before and 3 months after Empagliflozin treatment. Mature, defined as CD62L+CXCR2+, aged (CD62L+CXCR2+), activated (CXCR4+CXCR2-), immature (CD16dimCD10dim), and pre-neutrophils (CD49d-CD101-) were evaluated in 3 out of 4 patients and compared with 8 healthy donors (HD) with the same timing.

At baseline ANC was 1.37 x 109/L. Empagliflozin was gradually increased up to 0.4-0.6 mg/kg/day. G-CSF was discontinued within the first month in P1 and P2. After 3-month treatment, median ANC increased to 2.56 x 109/L. Clinical improvement was noticed. P1, the only patient who suffered from recurrent otitis, did not experience any further infection. Skin and mucosal lesions markedly decreased or were absent in P2 and P3. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) improved from severe to moderate (P3) or was under remission (P4). Organomegaly remained unchanged in all but P1, whose splenomegaly decreased. P3 and P4 reported hypoglicemia, effectively treated with diet-modifications.

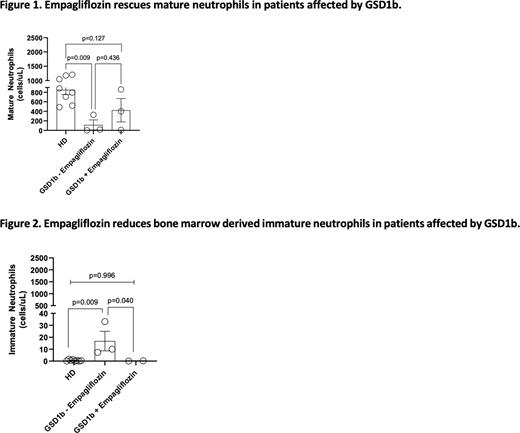

Baseline mature neutrophils were significantly lower in GSD-Ib patients compared to HD (114±106 cells/µL versus 852±98.1 cells/µL in HD, p=0.009), and increased following Empagliflozin treatment (423±246 cells/µL) with no difference compared to HD (p=0.127; Fig1). Aged and activated neutrophils did not change. Nonetheless, we noticed increased activated neutrophils in 2 out of 3 children as compared to baseline (123 to 680 in Pt3 and 41 to 375 cells/µL in Pt2).

Immature neutrophils, higher in GSD1b patients compared to HD (16±8 cells/µL vs 1±0.2 cells/µL respectively, p=0.009), significantly decreased following Empagliflozin treatment (0.2±0.1 cells/µL, p=0.040 versus pre-treatment) with results comparable to HD (p=0.996; Fig2). Pre-neutrophils did not vary between patients and HD.

Neutrophils' metabolism, and neutrophils' demand of glucose, changes during maturation from immature to mature. Mature neutrophils are co-opted in lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and skin2. The observation that the clinical improvement during Empagliflozin treatment was not related to the merely increase of ANC led Wortmann et al.1 to speculate about a shift toward mature neutrophils. This improvement was thought to explain the recruitment of neutrophils at the sites of infection and their capacity to kill bacteria. Our data extend the existing knowledge regarding the efficacy of Empagliflozin in GSD-Ib, supporting that the beneficial effect is not only reflected in the improvement in total ANC but also in the increase of mature neutrophils, resulting in reduced infections in one of our patients.

Our data also show the reduction of immature neutrophils. As already reported1, Empagliflozin reduces the burden of inflammatory conditions in GSD-Ib patients. We hypothesize that Empagliflozin reduces inflammation in GSD1b by lowering this neutrophil subset, whose concentration increases during either chronic and acute immunologic stress3.

In summary, we highlight, for the first time, the modifications in neutrophils' distribution during Empagliflozin treatment, which increases mature and decreases immature neutrophils. Larger studies with longer follow-up are required to assess that changes in these subsets imply a reduction of infections and chronic inflammation in GSD-Ib.

References 1.B.Wortmann, et al. Blood (2020).

2.Ballesteros I, et al. Cell (2020).

3.Drifte G et al. Crit Care Med (2013).

Disclosures

Biondi:Amgen: Honoraria; Incyte: Consultancy, Other: Advisory Board; Bluebird: Other: Advisory Board; Novartis: Honoraria.

Author notes

Asterisk with author names denotes non-ASH members.