In this issue of Blood, Penter et al1 paint a picture of a leukemia bone marrow microenvironment that is immunologically distinct from that of many solid tumors. They present hypothesis-generating results from cutting-edge correlative studies on samples from a phase 1 clinical trial (NCT02890329) combining the CTLA-4 blocking monoclonal antibody ipilimumab with decitabine for patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes. Effective therapies are greatly needed for this patient population, and immune checkpoint blockade has yielded remarkable successes in solid tumors.2,3 The trial was motivated in part by responses to ipilimumab monotherapy seen in patients with relapsed myeloid neoplasms, primarily extramedullary, after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).4 In the current cohort of patients with predominantly bone marrow disease, the activity of combination therapy was modest in both post-HCT and HCT-naïve individuals and appeared to be primarily driven by decitabine-induced cytoreduction5; however, the authors take advantage of the extensive samples collected to explore the immunobiology underlying response and nonresponse to CTLA-4 blockade.

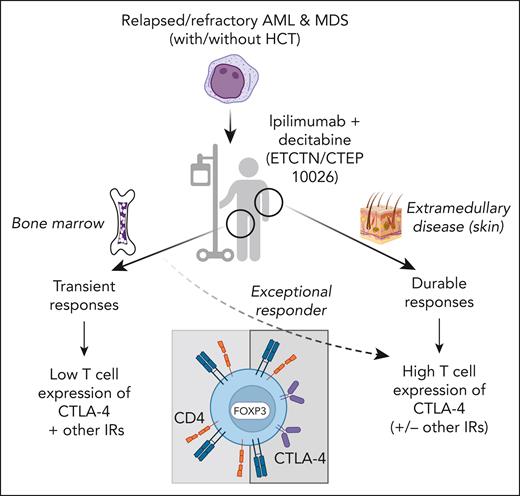

Among their findings were that ipilimumab treatment led to the recruitment of CD4+ regulatory T cells to the bone marrow, in contrast to the recruitment of CD8+ T cells observed previously in patients treated with CTLA-4 blockade with extramedullary disease.6 Moreover, in the current cohort of patients, the authors observed increased levels of soluble CD27 and CXCL3, hinting that ipilimumab might sometimes create conditions that inhibit rather than promote antileukemic T-cell activity. Examination of a set of genes (PDCD1, CTLA4, TIGIT, HAVCR2, TOX, LAG3, and ENTPD1) associated with T-cell dysfunction in solid tumors revealed that few bone marrow–infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells express these genes compared with tumor-infiltrating T cells and suggests that the effect of CTLA-4 blockade may have been limited by a lack of target. Supporting this notion, in extramedullary disease, in which durable responses to ipilimumab were more common, CTLA-4– and forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3)–expressing T cells were found infiltrating the tumor sites. In addition, marrow-infiltrating T cells from an exceptional responder to ipilimumab and decitabine showed relatively high expression of CTLA-4, FOXP3, and programmed cell death protein 1 in a baseline sample, suggesting that the presence of CTLA-4–expressing T cells is key to response (see figure). Although it may seem counterintuitive that disinhibiting inhibitory T cells (immune checkpoint blockade targeting regulatory T cells) could facilitate clinical responses, increased regulatory T cells have been associated with improved responses to immune checkpoint blockade in some solid tumors.7,8

Patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were treated with ipilimumab and decitabine on NCI Experimental Therapeutics Clinical Trials Network/Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program 10026 (NCT02890329). Patients with postallogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) relapse or HCT naïve were enrolled in 2 separate cohorts. Responses in patients with bone marrow disease were observed but were transient, whereas more durable responses were seen in patients with extramedullary disease (eg, leukemia cutis). In patients with bone marrow disease, ipilimumab led to the recruitment of CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells but not CD8+ T cells to the marrow, and expression of inhibitory receptors (IRs), including CTLA-4, was infrequent on CD4+ and CD8+ marrow-infiltrating T cells. In contrast, T cells infiltrating extramedullary relapses expressed CTLA-4 and FOXP3, along with markers of resident memory. One exceptional responder with bone marrow disease had a preponderance of CTLA-4+ FOXP3+ T cells at baseline, suggesting the overall modest responses seen in bone marrow disease were due to lack of target for CTLA-4 blockade. Overall, the results from this study indicate that the bone marrow environment has distinct effects on T cells that might render immune checkpoint blockade less effective for bone marrow resident malignancies. Created with BioRender.com.

Patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were treated with ipilimumab and decitabine on NCI Experimental Therapeutics Clinical Trials Network/Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program 10026 (NCT02890329). Patients with postallogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) relapse or HCT naïve were enrolled in 2 separate cohorts. Responses in patients with bone marrow disease were observed but were transient, whereas more durable responses were seen in patients with extramedullary disease (eg, leukemia cutis). In patients with bone marrow disease, ipilimumab led to the recruitment of CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells but not CD8+ T cells to the marrow, and expression of inhibitory receptors (IRs), including CTLA-4, was infrequent on CD4+ and CD8+ marrow-infiltrating T cells. In contrast, T cells infiltrating extramedullary relapses expressed CTLA-4 and FOXP3, along with markers of resident memory. One exceptional responder with bone marrow disease had a preponderance of CTLA-4+ FOXP3+ T cells at baseline, suggesting the overall modest responses seen in bone marrow disease were due to lack of target for CTLA-4 blockade. Overall, the results from this study indicate that the bone marrow environment has distinct effects on T cells that might render immune checkpoint blockade less effective for bone marrow resident malignancies. Created with BioRender.com.

Taken together, the findings of this study suggest that T cells in the leukemic bone marrow microenvironment are not the same as T cells infiltrating solid tumors, and thus lessons learned in the setting of solid malignancies may not apply. Determining whether these findings are consistent in larger cohorts of patients with intramedullary and extramedullary myeloid malignancies is a crucial next step. Examining bone marrow T cells in lymphoid malignancies could help answer whether it is the marrow microenvironment, the type of malignancy, or both that influences T cells most. Dissecting whether, or when, regulatory T cells are friend or foe in myeloid malignancies could lead to novel therapeutic approaches. Finally, immune and clinical responses following CTLA-4 blockade in extramedullary myeloid neoplasms appear to be more similar to those seen in solid tumors than in bone marrow disease, which points to ipilimumab as a potential and much-needed new therapy for extramedullary disease and suggests that when it comes to antitumor T cells, location is key.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.