In this issue of Blood, Sacco and colleagues provide insights into the overbearing influence of the domineering T regulatory (Treg) cells that interact with malignant B cells, via the CD40/CD40-ligand axis, to facilitate evasion of the immune system in Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM).1 The treatment of this immunoglobulin M–secreting B-cell lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma has witnessed remarkable progress in recent years.2,3

The crucial role of the microenvironment in nurturing cancer cells is well recognized in a variety of cancers, and WM is no exception.3 The Treg cells express forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), a key transcription factor, which facilitates their development, maintenance, and function. Through a host of sophisticated regulatory mechanisms, they maintain immune homeostasis, moderate pathogen-induced inflammation, and preserve peripheral tolerance by controlling specific, potentially self-reactive effector T lymphocytes that have escaped the central tolerance mechanisms.4-8 Conversely, Treg-cell deficiency and mutations in FoxP3 contribute to the development of autoimmune diseases.

To test the hypothesis that the potential Treg cell–mediated immunosuppressive milieu modulates the biology of WM, with resultant lymphoplasmacytic cell proliferation, the investigators embarked upon a series of elegant experiments designed to methodically decipher the cross talk between the WM cell and the regulatory cell.

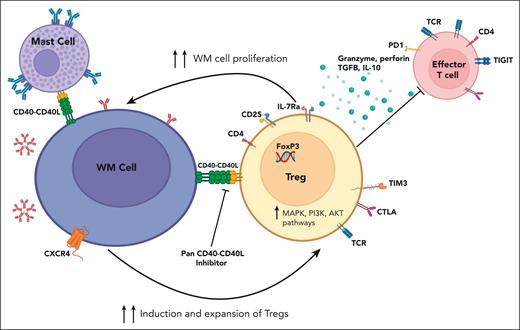

Through the flowcytometric analysis of the bone marrow immune microenvironment of a WM transgenic murine model, Sacco et al first demonstrated an increased population of exhausted CD4+ T cells, with preponderance of immunosuppressive CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells in the T-cell compartment, compared with that of the control mice. The Treg cells recruited by the murine WM cells were characteristically highly proliferative in comparison with those enlisted by the healthy B lymphocytes of the control mice. Next, on bulk RNA sequencing, the transcriptome profiling revealed a distinct signature of the Treg cells derived from patients with WM, markedly enriched for FOXP3 target genes and genes related to interferon and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), leading to enhanced immunosuppressive properties. Their induction and proliferative capacity were appreciably elevated as well as demonstrated by the enrichment of progrowth and survival genes, including the MAPK- and PI3K/AKT-related genes in comparison with the healthy donor (HD)-derived Treg cells. Subsequent Treg-cell induction assays demonstrated a significant increase in CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells when CD4+CD25− non-Treg cells were cocultured in transwell with BCWM.1/MWCL-1 WM cell lines or CD19+ cells derived from patients with WM versus HD-derived CD19+ B cells, highlighting the differential impact of the malignant and normal B-cell populations in harnessing the immune system via soluble factors. An enhanced Treg-cell proliferation, promoted by the WM cells, was also evident in the Ki-67 flowcytometric analysis. Furthermore, compared with their normal counterpart, the Treg cells derived from patients with WM exhibited a higher expression of Treg effector molecules (which in turn can inhibit the effector immune cells) and a greater capacity to curb the conventional T-cell growth, creating a highly immunosuppressed habitat for unrestrained WM cell growth (see figure).

Waldenström macroglobulinemia cell (B cell)-Treg cell cross talk. WM cells modulate Treg cell expansion and promote their immunosuppressive activity through CD40/CD40-ligand interaction, creating an immunosuppressive milieu, which in turn supports WM cell proliferation. CD40/CD40L axis blockade reverses this phenomenon. IL-10, interleukin-10; TCR, T-cell receptor; TGFB, transforming growth factor β. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Waldenström macroglobulinemia cell (B cell)-Treg cell cross talk. WM cells modulate Treg cell expansion and promote their immunosuppressive activity through CD40/CD40-ligand interaction, creating an immunosuppressive milieu, which in turn supports WM cell proliferation. CD40/CD40L axis blockade reverses this phenomenon. IL-10, interleukin-10; TCR, T-cell receptor; TGFB, transforming growth factor β. Figure created with BioRender.com.

The investigators then endeavored to unravel the underlying molecular mechanisms at the helm of the identified Treg-cell induction by conducting single-cell RNA sequencing on the entire cell population obtained after the Treg-cell induction assay. This approach permitted them to map Treg cells to a cluster with a distinct gene set that was enriched for FOXP3, CD25, IL-7R genes (cluster 3) among the total of 12 clusters identified, as well as a corresponding cluster of T cells potentially transitioning into Treg cells with a milder expression of the same gene set (cluster 5).

Alterations in the CXCR4 gene are encountered in up to 40% of patients with WM and are widely known to drive increased drug resistance.3 Using the HD-derived CD19+ B cells as control, the induction of the Treg cells cocultured with the WM cells that harbored CXCR4 mutation(s) was more pronounced than that observed with wild-type CXCR4 WM cells.

Finally, the researchers examined the WM- and Treg-cell cross talk at the single-cell level. They could pinpoint the distinct expression pattern of intercellular adhesion molecule 2 (ICAM2) as well as 3 genes from the TNF family, including CD40, TNF, and TNFSF14, with the CD40 gene expression being maximal and confined to the B-cell clusters from the WMCL1 model. Notably, the CD40/CD40-ligand axis was found to be instrumental in this dialogue between CD40-expressing WM cells and CD40-ligand+ Treg cells, creating a permissive tumor microenvironment (see figure). Using DR-1C21045, a potent blocker of this axis, Sacco and colleagues could abrogate the symbiotic interaction and demonstrate attenuation of the immunosuppressive T cells, thereby impeding WM cell growth.

This putative channel also mediates, as shown previously, the interaction between the CD40+ WM cells and the intimately associated CD154 (CD40 ligand or TRAP)-expressing bone marrow mast cells, leading to lymphoplasmacytic cell expansion (see figure).9

It is, however, essential to not forget that the interaction between the transmembrane protein receptor, CD40, and its natural ligand, CD40L, evokes a host of physiological immune activities, including, but not limited to, class switching, affinity maturation, cytokine secretion, differentiation, development, and adhesion of B cells. CD40 is also expressed on activated dendritic cells, and CD40 signaling allows them to become more effective antigen-presenting cells. CD40/CD40L-dependent bidirectional cross talk, important for host defense against cancers, occurs between the dendritic cells and lymphocytes. Further complicating the picture is the discordant observations suggesting that although in some indolent B-cell malignancies, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, follicular lymphoma, and hairy cell leukemia, CD40/CD40L pathway promotes lymphomagenesis and progression, in others, such as Burkitt lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, it induces malignant cell apoptosis.7,8,10 Moreover, previous studies with dacetuzumab (SGN-40), a humanized anti-CD40 agonistic monoclonal antibody, and lucatumumab (CHR 12.12/HCD122), a fully humanized anti-CD40 antagonistic monoclonal antibody, have only demonstrated modest activity in B-cell malignancies.7,8

Whether in vivo disruption of this functional axis would translate into superior control of WM, similar to that noted in the preclinical model, remains to be established, as is the potential advantage of circumventing the development of autoimmune disorders, likely to be encountered with the Treg-cell ablative approaches. Nonetheless, this exhaustive work provides the framework to facilitate future studies involving innovative targeting and disruption of an ostensibly crucial communication channel between the host and the unwanted lymphoplasmacytic cells.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: P.K. has received research funding from Amgen, Regeneron, BMS, Loxo Pharmaceuticals, Ichnos, Karyopharm, Sanofi, AbbVie, and GSK and has provided consultancy or served on the advisory boards of BeiGene, Pharmacyclics, X4 Pharmaceuticals, Kite, Cellectar, Oncopeptides, GSK, AbbVie, and Sanofi. J.J.C. has received research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Cellectar, Pharmacyclics, and TG Therapeutics and is a consultant for AbbVie, BeiGene, Janssen, Kite, and Pharmacyclics.